Introduction

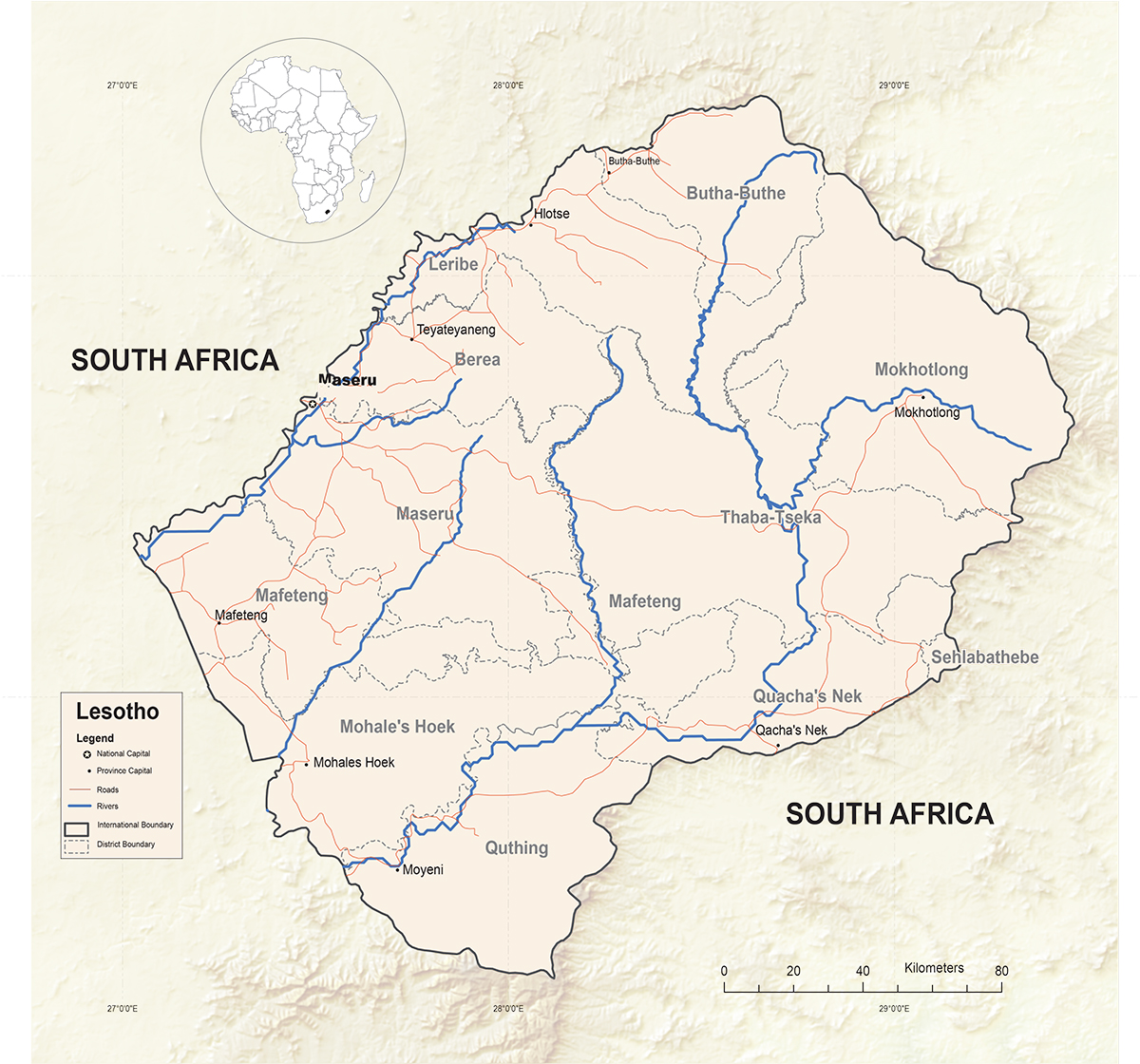

Since the events of 30 August 2014 in Lesotho, when a coup d’état was reported to have been attempted against the then-prime minister of the Kingdom of Lesotho, Thomas Motsoahae Thabane – which subsequently forced him to flee and seek refuge in South Africa – the Southern African Development Community (SADC), of which Lesotho is a founding member, has been occupied with efforts to manage and resolve the ensuing conflict in the mountain kingdom. Lesotho is a prominent conflict agenda item at SADC summits and extraordinary summits, having experienced political disturbances and internal conflicts before in 1974, 1986, 1991, 1994, 1998 and 2007. Throughout the country’s history of conflict, SADC has facilitated interventions in collaboration with neighbouring states – specifically South Africa and Botswana – in search of peace and political stability. However, it is disturbing that even after the February 2015 snap elections, there has not been a full restoration of peace and normalcy in Lesotho. The reported assassination of the former Lesotho Defence Forces (LDF) army chief, Brigadier Maaparankoe Mahao, on 25 June 2015 just outside Maseru, is a cause of concern and frustrates the efforts invested thus far in the peace process. This article presents an assessment of the efficacy of SADC’s intervention to resolve the Lesotho crisis, progress made so far and prospects for restoring peace and political stability.

SADC Conflict Resolution Instruments and Machinery

At its formation in 1980 in Lusaka, Zambia, the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) aimed to advance the cause of liberating southern Africa and reducing its dependence on the then-apartheid South Africa. The transformation of SADCC into SADC in 1992, upon the signing of the SADC Treaty and Declaration at the Windhoek Summit in Namibia, was later followed by the landmark amendment of the SADC Treaty in Mach 2001. This amendment established institutional mechanisms that were key in the delivery of the organisation’s mandate. Among these mechanisms were the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation (OPDSC) and the related Troika.1

The OPDSC, as provided for under Article 2 of the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation and signed by the SADC member states in Blantyre, Malawi in August 2001, seeks to “promote peace and security in the Region”, and one of its specific objectives is to “prevent, contain and resolve inter and intra-state conflict by peaceful means”.2 The OPDSC presents a framework upon which member states3 coordinate peace, defence and security issues, and comprises two committees that make key decisions – the Inter-State Defence and Security Committee (ISDSC) and the Inter-State Politics and Diplomacy Committee (IPDC).

SADC therefore always strives to resolve emerging conflicts peacefully within and between member states through preventive diplomacy, negotiation, conciliation, good offices, adjudication, mediation or arbitration. Other than the latest efforts in Lesotho, SADC has historically been involved in interventions to resolve conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Madagascar and Zimbabwe, with military interventions backed by member state armies in the DRC (1997) and Lesotho (1998). The success of SADC interventions in resolving conflicts has been varied, given the challenges presented by the conflicts, as they were different in terms of nature, causes, dynamics and level of complexity.

The Lesotho Conflict

The Lesotho conflict can only be fully understood with a sufficient exposition of the country’s historical context. The country has a long history of political instability and has experienced “high levels of factionalism, political tension, and violent conflict especially during and after elections” since its independence in October 1966.4

The outcome of the first Lesotho elections in 1966, which were won by the Basotho National Party (BNP), was largely disputed and was followed by post-election violence. The next elections, in 1970, were declared null and void by the ruling BNP, “fearing political defeat” by the opposition Basutoland Congress Party (BCP).5 This led to massive protests and instability.

In 1986, a coup ousted the BNP-led government and established a seven-year military rule.6 After the disputed elections in 1993, which were won by the BCP, an army-backed ‘palace’ coup took place in August 1994. This was preceded by the assassination of the deputy prime minister, Selometsi Baholo, and a mutiny within the national army and police.7 King Letsie III subsequently dissolved the democratically elected BCP government and Parliament, and replaced it with the Provisional Council of State. This provoked widespread protests in Lesotho.

Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe jointly facilitated a peace process in 1994, which saw a return of the BCP-led government to office. The 1998 elections were won by the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) – but again there were allegations of electoral fraud, which led to violent protests and political tension.8 Upon invitation from the government and opposition parties in Lesotho, South Africa set up a commission of enquiry – comprising South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe – to audit the elections. The findings of the commission were questioned on the basis of credibility and reliability, leading to a string of events that ended in army mutinies and an attempted coup d’état. In September 1998, SADC intervened militarily through Operation Boleas, led by South African National Defence Force (SANDF) and Botswana Defence Force (BDF) troops, to “prevent anarchy and restore order”.9

There were also post-electoral contestations, violence, assassinations and attempted assassinations in the aftermath of the 2007 elections, which were won by the LCD. The opposition alleged electoral manipulation. SADC Troika facilitators mediated dialogue between the key stakeholders in the Lesotho conflict – the government, the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) of Lesotho, the ruling party and the opposition parties. The outcome was an agreement to amend electoral laws, and constitutional amendments paving the way for the 2012 elections.

The current conflict being experienced in Lesotho is traceable to the 2012 National Assembly elections, when then-Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili’s Democratic Congress (DC) failed to attain the required outright majority. This resulted in a three-party coalition government of Thomas Thabane’s All Basotho Convention (ABC), Deputy Prime Minister Mothetjoa Metsing’s LCD and the BNP. This has frequently been referred to as an ‘uneasy’ coalition.

The deputy prime minister alleged that Thabane was making crucial government decisions without consulting the two coalition partners, and that such conduct affected the coherence of the coalition government.10 After efforts to call for mediation by the Christian Council of Lesotho (CCL) were not fruitful, Metsing withdrew from the coalition and entered into an alliance with Mosisili’s DC.

Thabane then prorogued Parliament, allegedly as a ruse to avoid a vote of no confidence by the newly formed coalition. This was approved by King Letsie III. Factions emerged, with Thabane backed by the police and Metsing having the support of the army. The conflict and tension was escalated by the prime minister’s decision to fire the LDF army commander, Lieutenant-General Kennedy Tlali Kamoli, and replaced him with Brigadier Maaparankoe Mahao. This was argued to be unprocedural and politically motivated.

It was reported that the police headquarters was attacked by the army, which claimed it was to prevent the police from arming mass protestors, in line with received intelligence. On 30 August 2015, Thabane reported an attempted coup d’état and fled to South Africa, alleging fear for his life. Metsing then assumed the premiership on an interim basis. Thabane accused his deputy of orchestrating a coup with army support, and immediately called for the deployment of peacekeepers into Lesotho to restore the status quo.

Pressure from the Regional and International Community

There was mounting pressure on Lesotho and the relevant actors to address the conflict, as numerous international organisations and the international community expressed concern and distaste over the alleged coup d’état in Lesotho. In a press release on 30 August 2014, the United States (US) State Department, through its spokeswoman, Jen Psaki, stated that “the US is deeply concerned by clashes between security forces today in Lesotho, and calls upon government officials and all parties to remain committed to a peaceful political dialogue and to follow democratic processes in line with the Lesotho Constitution and principles of rule of law” to resolve the conflict.11 Ban Ki Moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN), together with Kamalesh Sharma, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth of Nations, condemned the reported coup and urged the parties to respect the rule of law and uphold democracy.

South Africa, through its Department of International Relations and Cooperation, also condemned the coup and called for the restoration of democracy, with South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) calling for the urgent intervention of the African Union (AU) and SADC. Of course, South Africa’s geopolitical and strategic economic interests cannot be overlooked – hence the country’s sense of urgency to resolve the Lesotho conflict. Lesotho is completely surrounded by South Africa, and is one of South Africa’s key strategic trading partners within the five-member Southern African Customs Union (SACU), in which South Africa is the dominant player. Lesotho currently imports close to 80% of its consumer goods from South Africa.12 In addition, South Africa has wider commercial interests in Lesotho, with several companies in “various sectors such as housing, food and beverages, construction, retail, hotels and leisure, banking, and medical services”.13 The two countries are also jointly engaged in Phase II of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), and also have standing water agreements – “a key pillar of South Africa’s water security strategy”, as they sustain the supply of over 700 million cubic metres of water to Gauteng province, South Africa’s economic hub.14

SADC Mediation and Facilitation to Resolve the Conflict

In early September 2014, shortly after the attempted coup, the SADC Troika on Defence, Politics and Security – made up of Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe – met to map the way forward. This was followed by a meeting between LDF Commander Tlali Kamoli and regional military officers from the SANDF, Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) and Namibia Defence Forces (NDF), to allow the return of the prime minister and guarantee national security.

The swiftness of SADC’s response to Lesotho’s conflict should be commended. Perhaps it is a sign that such regional organisations are now convinced that without political stability in the region, the prospects of attaining regional economic development will be crippled.

Chairperson of the OPDSC, South African president Jacob Zuma, led the talks between Thabane, Metsing and the Lesotho Minister of Gender and Sports, Morena Maseribane. This diplomatic offensive – which SADC prudently opted for rather than a military offensive – procured results. Thabane returned safely to Maseru on 3 September 2014 after SADC agreed on a low-key security mission to accompany him, with an assessment mission from South Africa having been dispatched to Lesotho ahead of him for reconnaissance.

SADC appointed a mediator, South African Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, to facilitate dialogue between the disputing political parties and the protagonists at the center of the power struggle. An agreement was reached to dissolve Parliament and hold a snap National Assembly election on 28 February 2015, instead of waiting for 2017 as had initially been set by law.

The February elections did not result in an outright winner, due to Lesotho’s electoral system of mixed-member proportional representation (MMPR). Out of the 80 constituencies, Thabane’s ABC won 40 seats, Mosisili’s DC won 37 seats and Metsing’s LCD won two seats, whilst Thesele Maseribane’s BNP won a single seat.15 However, the MMPR electoral model meant that 80 seats are allocated based on constituency votes, whilst the remaining 40 seats are allocated to reflect the share of the national vote along a 80:40 ratio.16 As a result, Mosisili, who had been prime minister from 1998 to 2012, once again became prime minister, whilst the incumbent deputy prime minister, Metsing, retained his position after the DC and ABC entered into a coalition.

The SADC Electoral Observation Mission (SEOM) and the AU concurred with the Lesotho IEC that the elections were free and fair. The Commonwealth of Nations Election Observer Group, headed by former Botswana president Festus Mogae, endorsed the elections as conducted in a “peaceful and orderly manner”, whilst the SADC Parliamentary Forum Election Observation Mission reported that the Lesotho elections were “free, fair, transparent, credible and democratic”.17

The reported fleeing of the main opposition leaders, including former prime minister Thabane, from Lesotho, allegedly for personal security reasons, and later the reported assassination of former LDF army chief, Brigadier Mahao, just outside Maseru on 25 June 2015, raised the concern of SADC leaders. SADC’s promptness in organising and hosting an Extraordinary Summit of the Double Troika on 3 July 2015 in Pretoria, South Africa was commendable. This summit was convened to consider reports from the SADC facilitator to Lesotho, Ramaphosa, and the report of the SADC Ministerial Organ Troika Fact Finding Mission, sent to assess the political and security developments in Lesotho. The Double Troika Summit, attended by Zimbabwe, South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Malawi, endorsed the report and recommendations of the SADC facilitator. It also approved the establishment of an oversight committee as an early warning mechanism in the event of signs of instability in Lesotho and to intervene as appropriate, in consultation with the SADC facilitator.18

Another outcome of the summit was the establishment and immediate deployment of an independent commission of inquiry to investigate the circumstances surrounding the death of Brigadier Mahao. The summit also agreed to send an independent pathologist to conduct an examination within a period of 72 hours, as requested by the prime minister of Lesotho. In addition, the summit urged the Government of Lesotho to create a conducive environment for the return of opposition leaders to the country.

How Effective has the SADC Intervention been?

In assessing the efficacy of SADC’s intervention, the key focus should be on the extent to which the regional organisation’s mediation and facilitation has achieved desired results. As spelt out in the joint statement issued by the SADC Troika on OPDSC and Leaders of the Coalition of the Kingdom of Lesotho on 1 September 2014 in Pretoria, the political and security situation in Lesotho had deteriorated and all the parties committed to working together to restore political normalcy, stability, law and order, peace and security. Thus, SADC’s role was established to mediate and facilitate such a process.

From the organisation and conduct of the Troika meeting to the appointment of Ramaphosa as SADC facilitator, the speed and coordination was smooth on the part of the regional organisation. The Troika meeting was also inclusive, as it involved the members of the Lesotho coalition government.

It must be understood that SADC’s philosophy in conflict resolution has traditionally and consistently anchored on dialogue and soft diplomacy, hence its reluctance to deploy the SADC Standby Force (SSF), which is a tool of the OPDSC, unless the security situation has deteriorated beyond negotiation.

The SADC mediation process should be credited for four clear achievements: facilitating the safe return of exiled ex-prime minister Thabane; the reopening of the Lesotho Parliament; agreement on the conduct of an early election; and the urgent deployment of an Observer Team on Politics, Defence and Security.

It should, however, be pointed out that SADC’s intervention fell short of sustainably addressing the key questions that are influential in the Lesotho conflict resolution equation. The mediators may have thought that a snap election was the panacea and prescription to the Lesotho conflict. Perhaps, with hindsight and insights into the political dynamics that gave rise to the conflict, there might have been foresight on imminent post-election mutinies and political disturbances. The key questions that triggered the conflict were the polarised loyalty within – and destructive political interference into – the operations of the LDF and Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS). This issue was later identified and flagged by the SEOM, SADC Parliamentary Forum Election Observation Mission, AU and Commonwealth of Nations Election Observer missions during the 28 February 2015 elections.

The Goodwill and Pre-deployment Assessment Mission undertaken by the SADC Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC) between 1 and 6 February 2015, before the deployment of the SEOM, rightly observed that the “politicised aspects of the [Lesotho] security agencies” needed “careful monitoring”, although the conduct of elections was consistent with the SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections.19 Similarly, the AU Election Observation Mission, headed by former Kenyan prime minister Raila Odinga, noted that “the two security agencies [the Lesotho army and the police] are reported to be politicised and were caught up in tensions between coalition government partners”.20

Judging by the nature of interventions and prioritised issues negotiated, this article maintains that SADC’s intervention in Lesotho managed and mitigated the conflict more than it resolved it. By definition, conflict resolution is different from conflict management, in that the former entails “the elimination of the causes of the underlying conflict, generally with the agreement of the parties” whilst the latter refers to the elimination, neutralisation or control of the means of pursuing either the conflict or the crisis”.21

Recommendations

Ideally, the SADC mediation should have facilitated an inclusive process that addressed the underlying causes of the Lesotho conflict. This should, however, have been undertaken in a manner that strictly respects the sovereignty of Lesotho, as contained in the SADC Treaty.

There is no denial that since 1966 – when the country gained independence – coups, attempted coups, assassinations, election disputes and political instability have become part of Lesotho’s political culture. The SADC mediator should facilitate a comprehensive root cause analysis. This will allow the stakeholders in Lesotho to collectively identify the real source of intractable post-election disturbances, persistent military and police mutinies, coups and political instability. Given the zero-sum attitude, political accusations and counter-accusations that seem to characterise political leaders in Maseru, it would need diplomatic tactfulness and tenacity on the part of the SADC mediator.

With this in mind, SADC should also still facilitate a shift from conflict management to conflict resolution with a transformational agenda. This conflict transformation agenda should involve all key players in the Lesotho conflict – that is, the government, civil society and other key stakeholders – to develop a comprehensive and sustainable framework of legal, political and institutional reforms that would drive socio-economic development in the country whilst assuring successive governments of the separation of powers between the executive, legislature and judiciary. This practical separation of powers will allow for checks and balances, especially with regard to abuse of office by the executive in making army or police force appointments, the prosecution of political opponents, the dissolution of Parliament and electoral manipulation. The LDF and LMPS should be professionalised and transformed to protect national interests so as to prevent the recurrence of mutinies, shifting loyalties, partisanship, coups and attempted coups that are now entrenched in the Lesotho political tradition.

Negotiations should also consider reviewing Lesotho’s MMPR electoral model. The MMPR ideally promotes representative democracy; history has proven that it has always produced hung parliaments and unstable governments founded on coalitions of political parties with divergent ideologies. However, electoral reforms should be augmented by the strengthening of electoral governance institutions, such as the IEC and judiciary, to prevent the recurring phenomenon of post-election political instability and attempted coups in the country.

Thus, unless the structural causes of conflict in Lesotho are addressed, lasting peace and political stability in the country may be elusive. The SADC mediator should therefore facilitate the inclusion of the abovementioned key issues within a comprehensive negotiation framework.

Conclusion

Conflict in Lesotho is largely entrenched in the country’s political history. It is from this historical perspective that the conflict should be fully addressed, taking into consideration the legal, political and institutional perspectives. SADC has managed to facilitate and mediate significant aspects of the conflict with a view to restoring peace, political stability and security. SADC interventions have been well-coordinated and coherent, whilst exhibiting a great sense of urgency. However, the regional organisation has the capacity to broaden the scope of its negotiations to encompass and incorporate the key issues flagged by election observer missions, with respect to the restoration of professionalism and depoliticisation of the LDF and LMPS, as a sustainable conflict resolution and preventive strategy. It is critical that the mediator facilitates a process that identifies the root causes of political instability in Lesotho, so as to develop sustainable interventions. In this respect, it will need sustained political energy and political will from the political leaders in Maseru to focus on the real issues of national importance that need reform, without being tempted by the selfish desire to secure political power only.

Endnotes

- Article 9A and Article 10A, Southern African Development Community (2001) ‘Agreement Amending the Treaty of the Southern African Development Community’, 14 August, pp. 7–8, Available at: <http://www.sadc.int/files/3413/5410/3897/Agreement_Amending_the_Treaty_-_2001.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2015].

- Article 2(2)(e) and Article 2(1) of the Southern African Development Community Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security Co-operation.

- The Southern African Development Community currently consists of 15 member states: Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Matlosa, Khabele (2007) Managing Post-election Conflict in Lesotho. Global Insight, 70, p. 2.

- Matlosa, Khabele (2006) Electoral System Design and Conflict Mitigation: The Case of Lesotho. In Austin, Reginald et al. Democracy, Conflict and Human Security: Further Readings. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), pp. 96.

- Motsamai, Dimpho (2015) Elections in a Time of Instability: Challenges for Lesotho beyond the 2015 Poll. Southern Africa Report (Institute for Security Studies), 3 (April 2015), pp. 2–3.

- Ngwawi, Joseph (2014) A Historical Perspective of Lesotho’s Political Crisis. Southern African News Features (SANF), 14 (48) (September).

- Likoti, J. Fako (2007) The 1998 Military Intervention in Lesotho: SADC Peace Mission or Resource War? International Peacekeeping, 14 (2), pp. 251–252.

- Neethling, Theo (1999) ‘Military Intervention in Lesotho: Perspectives on Operation Boleas and Beyond’, The Online Journal of Peace and Conflict Resolution, 2.2, p. 1, Available at: <http://www.operationspaix.net/DATA/DOCUMENT/6107~v~Military_Intervention_in_Lesotho__Perspectives_on_Operation_Boleas_and_Beyond.pdf> [Accessed 17 July 2015].

- Kwisnek, Ella (2014) ‘Was there a Coup or Not?’, Friends of Lesotho Newsletter, Third Quarter (November), Available at: <http://www.friendsoflesotho.org/wp-content/uploads/FOL_Newsletter_3QTR_2014.pdf> [Accessed 29 June 2015].

- Psaki, Jen (2014) ‘Political Tensions in Lesotho’, Press Statement, US Department of State, 30 August, Washington DC, Available at: <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2014/231188.htm> [Accessed 25 June 2015].

- African Development Bank/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/United Nations Development Programme (2014) ‘The African Economic Outlook Report on Lesotho, 2014’, p. 6, Available at: <http://www.africaeconomicoutlook.org> [Accessed 12 June 2015].

- South African Government (n.d.) International Relations. In South Africa Yearbook 2013/14, p. 256, Available at: <http://www.gov.za/about-sa/international-relations> [Accessed 12 June 2015].

- Klasa, Adrienne (2014) ‘South Africa Fears for Business Interests, Water Supply in Lesotho “Coup”‘, This is Africa, 3 September, Available at: <http://www.thisisafricaonline.com/News/South-Africa-fears-for-business-interests-water-supply-in-Lesotho-coup?ct=true> [Accessed 29 June 2015].

- Independent Electoral Commission of Lesotho (2015) ‘National Assembly Election 2015 – Results’, Available at: <http://www.iec.org.ls/> [Accessed 29 June 2015].

- Independent Electoral Commission of Lesotho (2015) ‘National Assembly Elections 2015 Fact Sheets’, p. 9, Available at: <http://www.iec.org.ls/images/iecdocs/facts_sheets.pdf> [Accessed 28 June 2015].

- The Commonwealth (2015) ‘Lesotho Election Observer Group Interim Statement’, 2 March, Available at: <http://thecommonwealth.org/media/news/lesotho-election-commonwealth-observer-group-interim-statement> [Accessed 15 July 2015]; and SADC Parliamentary Forum (2015) ‘Interim Mission Statement by the SADC Parliamentary Forum Election Observation Mission to the 2015 Lesotho National Assembly Elections’, Delivered by Honourable Elifas Dingara, Mission Leader, Lesotho Sun Hotel, Maseru, Lesotho, 2 March, p. 9, Available at: <http://sadcpf.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=126&Itemid=117> [Accessed 1 July 2015].

- Southern African Development Community (2015) ‘Communiqué: Extraordinary Summit of the Double Troika’, 3 July, Pretoria, Available at: <http://www.sadc.int/files/8114/3598/7203/Draft_Communique_on_3_July__2135hrs_corrected.pdf> [Accessed 16 July 2015].

- South African Department of International Relations and Cooperation (2015) ‘SADC Electoral Observation Mission (SEOM) to the Kingdom of Lesotho, Statement by Honourable Maite Nkoana-Mashabane (MP), Minister of International Relations and Cooperation of the Republic of South Africa, and Head of the SEOM to the 2015 National Assembly Elections in the Kingdom of Lesotho, Maseru, 02 March 2015’, Available at: <http://www.dfa.gov.za/docs/speeches/2015/mash0302.htm> [Accessed 22 June 2015].

- African Union (2015) ‘African Union Election Observation Mission to the 28 February 2015 National Assembly Elections in the Kingdom of Lesotho: Preliminary Statement’, 2 March, p. 4, Available at: <http://www.au-elections.org/documents/AUEOMPSL.pdf> [Accessed 15 July 2015].

- Essuman-Johnson, Abeeku (2009) Regional Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis of Two African Security Complexes. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 3 (10), pp. 409–422.