Armed conflicts that need constructive measurement are rampant in various corners of the world. Currently, there are wars occurring in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Armed conflict can be understood as a battle between two parties, at least one of which is a state government, over a government or territory, using armed forces.1Kunkeler, J. & Peters, K. (2011) ‘“The boys are coming to town”: Youth, armed conflict and urban violence in developing countries’, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 5(2), 277-291 The notion of conflict is evolving along with understandings of states, borders, relationships, actors, issues, and globalisation. Mary Kaldor described this expanded understanding as ‘New Wars,’ which applies to the 2020 Ethiopian armed conflict.2Kaldor, M. (2007) New and old wars: Organised violence in a global era, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

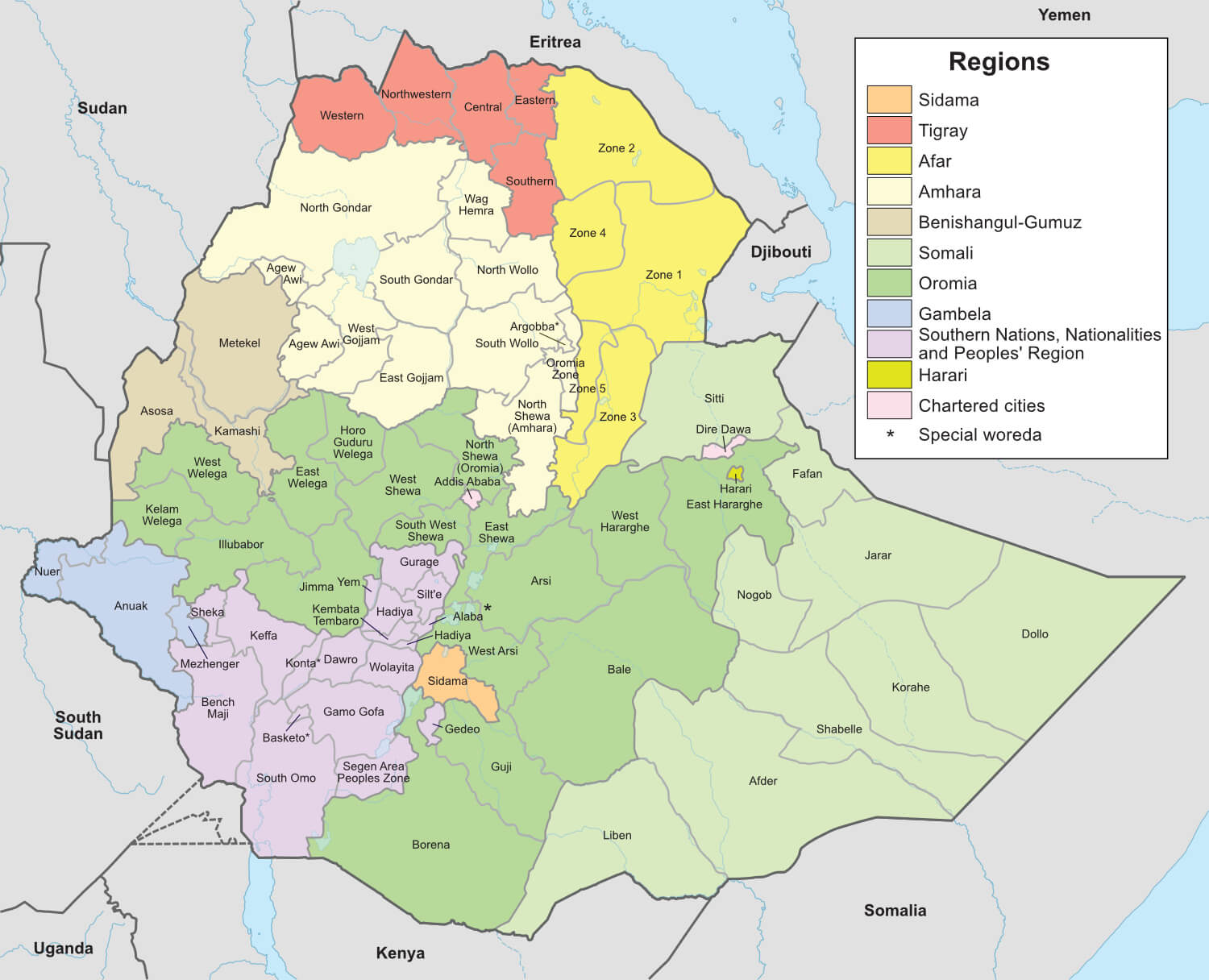

Ethiopia maintained its independence during the colonial period and emerged with its present borders and ethnic make-up at the end of the 19th century due to the territorial expansion undertaken by Emperor Menelik II (1889-1913). However, the history of the country is riddled with intra- and inter-state conflicts and it has experienced acute political and economic contradictions.3Kefale, A. (2013) Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Ethiopia: A Comparative Study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz Regions, Doctoral thesis, Department of Political Science, Leiden University The country has been a federal republic since 1994, with the official name of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, subdivided into nine ethnically based regional states (Killil), each with a large degree of autonomy, and two autonomous cities with regional state status, namely Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.4Federal Government of Ethiopia (1995) Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa: Federal Government of Ethiopia

Hassan Sheikh Mohamud in Mogadishu on 9 June 2022. ATMIS Photo/Fardosa Hussein.

Despite being undertaken to resolve ethnic conflicts, the federal restructuring of Ethiopia merely changed the conflict dynamics, including decentralising them, while also creating additional local inter-ethnic struggles.5Kefale, A. (2013) Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Ethiopia, op. cit.; Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia, 2020-2021: a study of war-making, media bias and policy struggle’, Working paper no. 152, African Studies Centre Leiden, Available at: http://www.ascleiden.nl/sites/default/files/j.abbink_working_paper_152_18-10-2021_final.pdf (17 January 2023) Under the direction of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the coalition Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) led the country for over 27 years. However, with protests that began in 2015, the regime was obligated to change its leadership and Prime Minister (PM) Abiy Ahmed was elected in 2018. Meanwhile, the relationship between ‘the TPLF-dominated Tigray Regional State and the Ethiopian federal government went sour after April 2018.’6Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit., p. 6 Furthermore, in 2019, Abiy dissolved the ruling coalition and formed a united Prosperity Party (PP), which the TPLF refused to join. These confrontations between the two parties escalated dramatically in 2020, developing into a full-scale war that eventually ended with the Pretoria Peace Agreement.

Nevertheless, there are various ideas provided by stakeholders about the measures that should be taken by the National Dialogue Commission (NDC) to address the conflict and enhance peace-building throughout Ethiopia. This paper tries to identify the root causes of the armed conflict and recommend possible measures to the NDC to help address the conflict and enhance peace-building in Ethiopia.

The paper is organised into five sections. The first section comprises an overview of war and conflict, while the second section deals with the northern Ethiopian armed conflict at a glance. Examination of the causes of armed conflict is discussed in the third and fourth sections of the paper. The conclusion and recommendations make up the final section of the paper.

The Armed Conflict in Northern Ethiopia at a Glance

Since April 2018, Ethiopia has undergone significant political liberalisation, which has garnered global acclaim. This period has seen expanded media freedom, the release of thousands of political prisoners, the reintegration of banned political groups, the appointment of non-partisan figures to key positions, and the revision of repressive laws. However, despite these positive developments, the country has simultaneously faced ongoing violent conflicts. 7Yusuf, S. (2019) ‘ISS: Drivers of ethnic conflict in contemporary Ethiopia’, 21 December, Ethiopia Insight, Available at: https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2019/12/21/iss-what-is-driving-ethiopias-ethnic-conflicts (20 February 2023)

After serious tension between the TPLF leaders and the other factions of the EPRDF, which later changed its name to the PP, an armed conflict began in northern Ethiopia on 4 November 2020. Developments in this war began with a well-prepared nightly assault of the then-ruling TPLF on federal army bases in Tigray Regional State.8Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit Immediately, the federal government controlled vast parts of Tigray but with little administration and government establishment. Later, after months of clashes with the federal army in Tigray, the ‘war was expanded by the TPLF into areas outside Tigray, where major abuses on local inhabitants were perpetrated’ and the fighting ‘expanded deeper into the Amhara Region to the important cities of Dessie and Kombolcha by early November 2021.’9Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Ethiopia Conflict in International Relations and Global Media Discourse’, Abdi Muda, 6 December, Available at: https://abdimuda.wordpress.com/2021/12/06/the-ethiopia-conflict-in-international-relations-and-global-media-discourse (30 January 2023) Moreover, there were consequences for neighbouring countries, including Egypt, Somalia, and Sudan.10Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit

The other important feature of the conflict is the engagement and interest of actors. As Ladini argued, contemporary armed conflicts feature complex networks of actors, interests, and dynamics.11Ladini, G. (2010) ‘The Political Economy of “New Wars”: Fundraising and Global Markets in Contemporary Armed Conflicts’, Africa Peace and Conflict Journal, 3(1), 1-12 Accordingly, in the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia, the two main contenders are the TPLF and the Ethiopian federal government. However, local self-defence militia groups, radical and violent TPLF-allied movements, such as the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), the Eritrean government, and those engaged in cyber-warfare are other actors in the conflict.12Abbink, J. (2021) ‘Understanding the War in Ethiopia: Causes, Processes, Parties, Dynamics, Consequences and Desired Solutions’, International Center for Ethno-Religious Mediation, 30 January, Available at: https://icermediation.org/the-war-in-ethiopia It is also clear that the armed conflict that started on 4 November 2020, produced far-reaching consequences in terms of human life, humanitarian issues, the economy, state sovereignty, and the state’s external relations.

Causes of Armed Conflict in Northern Ethiopia

Understanding the causes of armed conflicts is crucial for preventing their escalation into full-scale warfare, bringing an end to the fighting, and maximising the chances of avoiding the return of war after a settlement.13Smith, D. (2004) ‘Trends and Causes of Armed Conflict’, In: Austin, A., Fischer, M. and Ropers, N. (Eds), Transforming Ethnopolitical Conflict, Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 111-127, p. 112 It is with this intention that this section of the paper attempts to identify the causes of armed conflict in northern Ethiopia.

As aforementioned, after continual tensions between the Tigray regional state authorities and the federal government, the northern Ethiopian conflict entered open warfare in November 2020. Even though there are various reasons for the armed conflict, the following are the main causes identified for the eruption of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Political-economic rivalry

Many scholars increasingly use both political and economic factors to investigate the nature of ethnic conflicts.14 For instance, John Markakis argues that in the Horn of Africa, the state, as ‘it controls the production and distribution of material and social resources,’ has become the object and instrument of conflicts.15Markakis, J. (1994) ‘Ethnic Conflict and the State in the Horn of Africa’, In: Fukui, K. and Markakis, J. (Eds), Ethnicity and Conflict in the Horn of Africa, London: James Currey, pp. 217-237, p. 217 If one follows this proposition, it is possible to argue that the federal restructuring of Ethiopia decentralises conflicts by bringing the resources of the state to local and regional levels.16Kefale, A. (2013) Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Ethiopia, op. cit Furthermore, in studying the political history of Ethiopia, one can find a struggle for dominance between regional powers and ethnically organised political groups.17Woldeyesus, S. and Endris, M. (2021) ‘Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Ethiopia: Imagining a post-TPLF order’, Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society, 9(1), 119-148; Teshale, T. (1995) The Making of Modern Ethiopia: 1896-1974, Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press For Teshale, there was a power struggle between officials from Tigray and Shewa (Amhara) for political supremacy.18Teshale, T. (1995) The Making of Modern Ethiopia, op. cit Kefale pointed out that the perennial nature of conflicts in Ethiopia can be attributed to the features of the Ethiopian state – its practice of exclusionary politics and the use of brute force to dominate the people of the country.19Kefale, A. (2013) Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Ethiopia, op. cit

It is clear that in northern Ethiopia, the Tigray regional state authorities and federal government authorities are in a competition for political-economic supremacy. According to Woldeyesus and Endris, the TPLF has established hegemonic control over economic, political, security, and other affairs during its 27 years of leadership.20Woldeyesus, S. and Endris, M. (2021) ‘Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Ethiopia’, op. cit For them, the leadership of the PP launched a counter-hegemonic movement aimed at deconstructing the ideologies and institutions inherited from the TPLF and replacing its dominance. Similar to the imperial and military regimes, the EPRDF practices hegemonic control, despite its promises of parliamentary democracy and federalism.21Kefale, A. (2013) Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Ethiopia, op. cit Hence, the struggle for domination and the discourse employed by the conflicting parties forced both parties to enter into armed conflict.

In his article ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia, 2020-2021: a study of war-making, media bias and policy struggle,’ Abbink argued that the background to the latest armed clashes in the north of Ethiopia are the multiple political and social crises that have plagued the ethnically-based federal system created in 1994.22Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit These crises have mostly been generated by persistent ethnic rivalries and clashes and the incessant disputes between regionally-based elites (particularly from the Tigray, Amhara and Oromo regions) for control over the federal government, institutions and finances.23Ibid

In elaborating on the causes of the armed conflict between the TPLF and the PP leaders, Abbink pointed out that for the TPLF elite in Mekelle, ‘the ultimate aim to regain power on the federal level was there from the start since April 2018.’24Ibid, p. 6 He further argued that the breaking point for the conflicting parties was about the holding of regional elections in Tigray against the federal order that had postponed them under the emergency law due to COVID-19.25Ibid Moreover, a ‘power struggle, an election, and a push for political reform are among several factors that led to the crisis.’26BBC (2021) ‘Ethiopia’s Tigray war: The short, medium and long story’, 29 June, Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54964378 (25 January 2023) Accordingly, the military offensive that began in November 2020 by the federal government against Tigray regional state is the culmination of escalating political tensions between PM Abiy and the TPLF.27Pellet, P. (2021) ‘Background, causes and consequences of the Tigray conflict in Ethiopia that started on November 4, 2020’, Research Institute for Religion and Society, Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355146017

People in Tigray registering to vote in the 2020 regional election during the COVID-19 pandemic (August 2020). Photo Credit: Mulugeta Atsbeha

Politicisation of ethnicity and history

As a legacy from the colonial period and the subsequent co-option of groups by external powers or by internal mismanagement and power struggles, identity has become politicised in many cases, with some identities privileged and others marginalised or perceptions of undue benefit by one group causing tensions that can result in conflict.28Gluhbegovic, R. (2016) ‘Types of Conflict in Africa: How do the APRM reports address conflict?’ Occasional Paper, Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA), Available at: https://vdocuments.site/types-of-conflict-in (13 April 2023) Hence, systems of governance can encourage cooperation or exacerbate identity conflict. An African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) country report describes ‘the Ethiopian style of governance as refreshing, but cautions that if it is not managed well the system can promote identity-based divisions and conflict.’29Ibid, p. 12 Accordingly, armed conflicts in Ethiopia are the result of misguided, undemocratic politics, ethnic ideology, elite interests disrespecting accountability to the population, and foreign interference.30Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit For Mehari, ‘all the protracted armed conflicts Ethiopians have fought, and the political problems they now face are questions with deep roots in the Ethiopian state.’31Mehari, T. (2020) ‘Op-Ed: Ending Ethiopia’s armed conflicts: a modest proposal’, Addis Standard, 15 December, Available at: https://addisstandard.com/op-ed-ending-ethiopias (20 January 2023) Like many other multi-ethnic ancient countries, Ethiopian history, nonetheless, impels contradictory impulses of glory and vanquish to its citizens.32Clapham, C. (2002) ‘Rewriting Ethiopian History’, Annales d’Ethiopie, 18(1), pp. 37-54

Starting from the day of his inaugural address on 2 April 2018, PM Abiy commenced an ideational confrontation against the TPLF, notwithstanding his indirect challenges, and largely refrained from explicitly attacking the TPLF and its core principles. In his speech, Abiy not only deconstructed many of the TPLF’s established symbolic and conceptual narratives about the state and its history, he also hinted at the future ideology of government – ‘Medemer’ and slashing Ethiopian history to a mere 120 years.33Woldeyesus, S. and Endris, M. (2021) ‘Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Ethiopia’, op. cit Moreover, Abiy’s discourses and use of terms like ‘daytime hyena’ (yeken jib in Amharic) help to politicise ethnicity, which contributed to the outbreak of the war.34Ibid, p. 138; Pellet, P. (2021) ‘Background, causes and consequences of the Tigray conflict’, op. cit TPLF officials themselves employed phrases such as ‘being the underdog,’ ‘Tigray people being targeted,’ ‘Tigray being under siege,’ and ‘Tigray genocide,’ which played a significant role in popular mobilisation.35Abbink, J. (2021) ‘The Politics of Conflict in Northern Ethiopia’, op. cit., p. 7 All these points indicate that the politicisation of ethnicity and historical narratives by ethnic elites are the main causes of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Contested political transition

The conflict is a result of ‘political system failure and the difficult transition from a repressive autocracy to a democratic political system.’36Abbink, J. (2021) ‘Understanding the War in Ethiopia’, op. cit Gluhbegovic stated that in many African countries, a catalytic environment for political conflict is the political transition from a single party to a multiparty system, from authoritarian rule to democratisation, and from conflict to peace.37Gluhbegovic, R. (2016) ‘Types of Conflict in Africa’, op. cit In Ethiopia, the contested transition began after the change in PM in April 2018. ‘The TPLF was the key party in the wider EPRDF “coalition” that emerged from armed struggle against the previous Derg military regime, and it ruled from 1991-2018,’ during which time ‘Ethiopia never really had an open, democratic political system.’38Abbink, J. (2022) ‘Understanding the War in Ethiopia’, op. cit

A man passes by a destroyed tank on the main street of Edaga Hamus, in the Tigray region, in Ethiopia, on June 5, 2021. Photo Credit: Yan Boechat/VOA

The conflict between the federal government and the Tigray regional state leaders has a much deeper origin than the sequence of events since 2018, including an ideological confrontation over how Ethiopia should define itself, that is, the sharing of power between the federal government and local authorities.39Pellet, P. (2021) ‘Background, causes and consequences of the Tigray conflict’, op. cit; Mehari, T. (2020) ‘Op-Ed: Ending Ethiopia’s armed conflicts’, op. cit In the words of Francis Deng, Ethiopia is facing a ‘war of visions’ for its future.40Mehari, T. (2020) ‘Op-Ed: Ending Ethiopia’s armed conflicts’, op. cit Furthermore, the tensions between these two actors ‘reflect broader, unresolved debates about Ethiopia’s transition and federal arrangements.’41US Institute of Peace (2020) ‘The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia: Testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations’, 3 December, Available at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/12/unfolding-conflict-ethiopia (24 February 2023) Accordingly:

Past mechanisms for political dialogue were no longer fit for this purpose amidst rapid political reforms, and parties with diverging views or resistant to the reforms either opted out of or were not included in new forums. The tensions are also anchored in unaddressed reports, documentation, and legacy of corruption, human rights abuses, and state repression under the TPLF’s leadership in the previous regime, along with allegations that the TPLF has been fomenting some of the disorder, violence and chaos during the transition period.42Ibid

The decision to postpone the anticipated August 2020 elections set the stage for the crisis between the TPLF and the PP.43Ibid This move came when the Tigray region chose to hold state-level elections in defiance of the federal government and without the involvement of the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE). This decision marked another step toward the violence that erupted in November.44Ibid

On the other hand, for some observers, while PM Abiy has been widely praised for the sweeping political reform programmes he implemented after taking power, all reforms have been conducted by processes tightly controlled by the executive rather than by more broadly based and transparent mechanisms. This has given the appearance that the primary objective of the reforms was to secure his control over key institutions and state functions.

Moreover, after the political changes in 2018, PM Abiy launched ‘a counter-hegemonic praxis, which seeks to undo and deconstruct everything “inherited from the past and uncritically absorbed.”’45Woldeyesus, S. and Endris, M. (2021) ‘Hegemony and counter-hegemony in Ethiopia’, op. cit., p. 135-136 Initially, Abiy succeeded in impeding the TPLF with the use of ideational and institutional tools. The leadership championed alternative ideologies and a new consciousness that aimed at replacing the one held by the TPLF. However, Abiy did not produce something new from the perspective of a hegemonic project. Instead, the years following his ascendancy can be read as episodes of doing politics within the orbit of an interregnum.46Ibid All these clashes and unclear visions between the conflicting parties in the transition or reform contributed to the outbreak of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Distorted state and nation-building experience

Unlike its predecessors, post-1991 Ethiopia adopted a federal state structure. However, many scholars in the field argue that the method and practice of the EPRDF state and nation-building caused political polarisation and destabilisation.47Berhanu, K. (2017) ‘Ethiopia: The quest for transformation under EPRDF’, In: Bereketeab, R. (Ed.), National Liberation Movements as Government in Africa, London: Routledge, pp. 203-217; Berhanu, K. (2018) ‘Nation-Building in Ethiopia: In Quest of an Enduring Direction’, Ethiopia’s Nation-Building Project Working Group symposium, Bishoftu, Ethiopia The EPRDF reconstruction of the state with exclusionary narratives and its nation de-building attempts are the causes for the destabilisation and insecurity of the country and its citizens.48Berhanu, K. (2017) ‘Ethiopia: The quest for transformation under EPRDF’, op. cit

By employing Mamdani’s theoretical framework of political modernity and national belonging, Matshanda argued that the civil ‘war is another manifestation of the failure of the Ethiopian state to deliver inclusive national belonging.’49Matshanda, N. T. (2022) ‘Ethiopia’s civil wars: Postcolonial modernity and the violence of contested national belonging’, Nations and Nationalism, 28(4), 1282-1295, p. 1283 Hence, even though giving identity recognition and self-autonomy is an important aspect of Ethiopian federalism, the ruling regime works by the divide-and-rule principle, which undermines the building of a strong state.

Extremist political culture

As Clapham argued, Ethiopia’s political culture is a major hindrance to building a stable and peaceful state. For him, Ethiopia has a state culture derived from its long imperial history and from the societies, especially of the northern highlands, which, despite the upheavals of revolution and social change, continue to exercise a strong influence.50Clapham, C. (2002) ‘Rewriting Ethiopian History’, op. cit According to Lidetu, Ethiopia’s political culture, which is characterised by political extremism, leads the country into disintegration.51Lidetu, A. (2021). Ethiopia in the Process of Giving Birth to Dictatorial System

Furthermore, the spillover effect of the 1960s Ethiopian student movements’ political polarisation and exclusionary narrative, the bitter ideological differences and violent infighting between the students’ movements, and the Derg shaped many of Ethiopia’s current intellectuals and leaders. Therefore, ideological and personal schisms within secretively organised parties and rebel groups have a spillover effect onto current attempts at Ethiopian democratisation.52Selassie, A. (1992) ‘Ethiopia: Problems and Prospects for Democracy’, William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, 1(2), 205-226 Hence, this kind of extremist political culture, which is against tolerance and negotiation, is one of the reasons for the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Conclusion

This paper critically examines the causes of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia which has resulted in far-reaching consequences on human life, the economy, politics, and general futurity of the state. A struggle for political and economic domination played a significant role in the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia. Furthermore, the politicisation of ethnicity and history and a contested political transition are among the main causes of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia. An extremist kind of political culture and a distorted way of state and nation-building in the previous period takes the lion’s share in terms of leading to armed conflict. To effectively address the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia, all stakeholders must take the underlying causes seriously and actively engage in peace-building efforts.