As the African Union (AU) has become a stronger actor in peace operations, coordination with the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) has risen in importance. Beyond working together on a case-by-case basis, such as the AU–United Nations (UN) hybrid mission in Somalia, the two organisations are seeking a broader and more complementary relationship. These were followed by recommendations stressing the importance of partnerships with regional organisations, from the High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations and the Secretary-General’s response to this seminal report. Yet, the issue of financing African peace operations has been a long-standing contentious issue, leaving the AU in a subordinate position and reliant on external donors to support its operations. This is all about to change, however, with the recent decision taken at the 27th AU Summit to introduce a 0.2% levy on imports, thus moving the two organisations towards a more complementary relationship.

The AU Peace Fund and New Import Levy

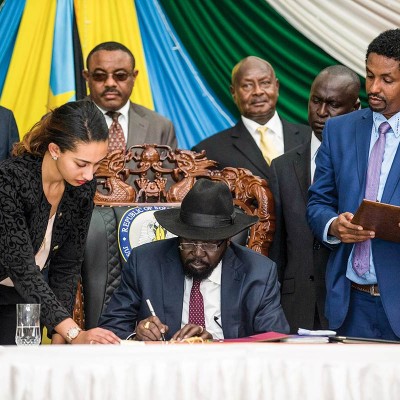

The 27th AU Summit, held in July 2016 in Kigali, Rwanda, resulted in several significant outcomes for the institution. However, it was the approval of a new funding model for the AU Peace Fund that has been heralded as a landmark move for African solutions to African problems. The AU chairperson, Idriss Déby, claimed it was the most important outcome of the summit. “For the first time, the continent is taking charge of its own destiny,” Déby said, adding that the plan would put an end to the “frustrating and troublesome dependency on outside financing”.1 The announcement moves the AU toward a more complementary relationship with the UN. The AU will now be able to begin funding its own peace operations and work towards achieving the overall strategy of the AU Peace and Security Architecture. This will move the AU away from being seen as only a subsidiary of the UN.

At the June 2015 AU meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, the Assembly decided that AU members would strive to achieve the following targets regarding financing: 100% of the operational budget, 75% of the programme budget and 25% for the peace support operations budget.2 In January 2016, African heads of state reiterated this decision by agreeing to pay at least 25% of the AU’s peace and security activities by 2020, with the remainder coming from the UN.3 To achieve this, outgoing African Development Bank president, Dr Donald Kaberuka, was appointed as the High Representative for the AU Peace Fund and asked to formulate a clear roadmap for financing these activities. The Kigali Summit approved Kaberuka’s recommendations – which will, if successful, ensure the Fund gains US$65 million a year from each of the continent’s five subregions (US$325 million in total) through a “community levy” of 0.002 (0.2%) on imports from outside the continent to cover the assessed contribution of all member states. This provision will increase to US$80 million per region by 2020, resulting in a total of US$400 million to fund the AU’s operating programme and peace and security operations budget.4 This levy should enable member states to fully fund the functioning of the AU Commission and cover 25% of African peace operations. The central beneficiaries will be the AU’s five peace and security programmes, which are a main focus of the AU’s work and development on the continent as a whole: the African Standby Force (ASF), the Panel of the Wise, the Continental Early Warning System, Capacity Building and Conflict Prevention.

Reliable and sustainable funding for the AU has been a challenge for the organisation for the past 15 years. In the 2016 financial year, of the AU’s US$416 million budget, only 40% is funded from AU member states’ contributions. These contributions, however, are based on each country’s total output (gross domestic product).5 This has resulted in a situation where more than 65% of member state contributions come from five countries – South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt, Libya and Algeria.6 The remaining funds come from international donors, which has resulted in a very strong interdependence and a subordinate role for African countries in decision-making.7 Not only did African peace operations led by the AU need UN authorisation, in accordance with Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, but leaders were also unable to credibly claim that Africa could solve its own problems. Now, the AU can, for the first time, have a predictable funding mechanism that will grow over time, providing it with more independence and greater leverage. The new funding model will also lay the groundwork for a more complementary relationship with the UN, which is a long-term goal of both institutions – as highlighted in the African Common Position on the Peace Operations Review, as well as the 2015 High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations and Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon’s response to its report.

Will the Fund Work?

Some question how the new levy will be managed and enforced within the AU. At the Kigali Summit, Kaberuka rejected suggestions that his proposal is too ambitious and said that because Africa is already organised into a number of free-trade zones, it can easily be implemented by 2017. The plan is based on the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Common External Tariff (CET), adopted in 2006, which is seen as a success in the region. The CET was designed to help expand ECOWAS’s Customs Union, as well as promote cooperation and integration among member states. The CET was adopted at the 29th Summit of the ECOWAS Heads of State and Government on 12 January 2006 in Niamey, Niger, and provided for the adoption of a four-band tariff structure made up of basic social goods (category 0), attracting an import duty of 0%; basic essential goods, raw materials, capital goods and specific inputs (category 1), attracting an import duty of 5%; intermediate goods (category 2) with an import duty of 10%; and finished goods (category 3) with an import duty of 20%. The 2006 Summit also provided for a number of taxes as part of the CET, including a community levy, statistical tax and certain accompanying measures. This levy was seen as a means of expanding ECOWAS’s Customs Union as well as promoting cooperation and integration among members and providing financing for the activities of the community, including initiatives around responding to security challenges. This has resulted in an increase in overall imports in the region.8

Similar plans have previously been presented to AU member states, including a plan put forward in 2014 by former Nigerian president, Olusegun Obasanjo, to initiate a levy on flights or hotel occupations. This plan aimed to initiate a US$2 levy on a stay hotel tax and a US$10 flight levy on flights to and from Africa. However, the plan was rejected, because it was felt that it would unfairly burden countries that rely on tourism and aviation for income. Tunisia, for example, is largely dependent on tourism because of its proximity to Europe and its favourable weather, and rejected the tourism taxes. “If we make the tax, we will become the (largest) contributor to the AU,” Tunisian ambassador to Nigeria, Hattab Haddaoui, said of the tourism levy.9

It seems, however, that the AU has realised that to genuinely gain independence, it must raise its own revenue. In the past, the AU had to forgo a number of projects, as it relied entirely on donor funding. Relying on donors for AU programmes compromises the organisation’s ability to respond to armed conflicts, said Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, the AU Commission’s chairwoman. “They do want to have money [so] they can at least start to do something if there is a crisis and when there needs to be preventative measures they can take without having to wait for months and months… because they don’t even have a small amount of money to start.”10 It seems the AU has now accepted that it must be funded by African countries because, as Pravin Gordhan, South Africa’s minister of finance, said in Abuja in 2014, “We should take some pride in our own sovereignty. Each country can manage some contribution.”11

The new financial plan requires immense administrative oversight, though, especially since certain products – such as medicines and fertiliser – would be excluded from the levy. Yet, Claver Gatete, Rwanda’s finance minister, told journalists that administrating the fund would not be a problem since the levy would be channelled directly from revenue authorities to the treasury. It would not figure in the budgets of countries, so it would not have the same impact as financing AU membership through regular channels. “The new formula is simple and automatic and doesn’t pose any budgetary constraints,” Gatete said,12 and it has seen success in some regions, for example ECOWAS, which has already implemented a similar levy to finance its Commission.

What is vital to the success of the fund is ensuring transparency and compliance, with a pledge to name and shame those who do not contribute. As Gatete stated, “The decision of heads of state is binding on all countries.”13 To ensure this, a committee of finance ministers will be charged with overseeing the process and checking compliance. Work will need to be done in this area, though. As it stands now, if a country defaults twice on its annual contributions, sanctions are supposed to kick in and these countries are not allowed to vote on AU decisions, such as the election of the new AU Commission chairperson – yet this is rarely implemented.

Despite these challenges, the AU Peace and Security Commissioner, Smaïl Chergui, is especially pleased with the new funding proposal, and travelled to New York the week following the summit to discuss it with the UN. The UN Secretary-General commended the AU leadership on achieving agreement well ahead of the initial objective of 2020. As well as improving African peace operations and the partnership between the AU and UN, this decision could also improve the relationship between the AU and Africa’s regional economic communities (RECs) in the provision of peacekeeping troops, which has, at times, been challenging.

Towards a Complementary Relationship

The AU has fought hard to change the narrative around the relationship with other institutions considered to be the political and financial big brothers of the AU, and there has been a growing recognition of the need to shift this narrative. As the AU becomes a stronger actor in peace operations, coordination with the UNSC has risen in importance. At the most recent Open Debate between the AU and UN, held in New York in May 2016, Under Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, Hervé Ladsous, said: “The African Union, directly or not, is the most important partner of the UN in peacekeeping.”14 Ethiopia’s Permanent Representative, Tekeda Alemu, stated at a seminar on the same topic that “the mutual dependence of the UN and the AU for effective peace operations has made their partnership indispensable for both”.15 This relationship is not only important because crises and conflicts in Africa take up the largest portion of time of the UNSC, but also because African capacities are an important resource for UN peacekeeping. Africa’s member states contribute close to 51% of all the UN’s uniformed peacekeepers, 60% of its international civilian peacekeepers and 80% of its national peacekeeping staff. This is an increase in contributions from 10 000 peacekeepers 10 years ago to 50 000 today.16 There is no denying the value the AU adds to UN missions, especially with stabilisation forces.

Further, through the development of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) – in particular the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the ASF – the AU and the regional economic communities (RECs) have become significant actors and an important resource in international peace operations.17 Practically, national, multinational and regional-led responses are fast to deploy and very capable of combating well-equipped and determined belligerents. The UN faces budget and administrative challenges relating to issues of member state contribution and political will challenges. UNSC members may be more inclined to endorse a regional mission, because these do not require personal troop contributions and are thus less costly in terms of budget and personnel. Linked to this, the introduction of the ASF and the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crisis means that there are troops already mobilised for immediate deployment.18

Ultimately, with the changing nature of conflict and the rise of violent extremism, there is a greater need for forces that can act where there is no peace to keep, and which can be tasked to neutralise the spoilers of peace. The AU has a proven track record of being able to deploy fast and the ability to use force to stabilise a conflict situation, as has been seen in Burundi, Central African Republic (CAR), Darfur and Mali. Such peace enforcement and counterterror operations fall outside the current UN doctrine on peacekeeping. On the other hand, the AU lacks a strong civilian capacity component, and thus does not have the capacity to develop multidimensional missions that can sustain peace over the long term. This is where the UN’s predictable funding and ability to recruit a large civilian component in every mission provide it with a competitive advantage. Hybrid missions such as the UN–AU Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) and the working relationship between the UN and the AU regarding the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) show that a strategic relationship is possible and is very useful in managing conflict on the continent.

The Quest for a Better Partnership

Recent developments have shown us that an effective relationship between the AU and UN is no longer optional but rather “an absolute necessity”,19 as the UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, El Ghassim Wane, stated. Over the past decade, there have been significant improvements in the relationship between the two institutions. UNSC members and AU PSC members started holding annual joint meetings in 2007, alternating between their respective headquarters. This is a noteworthy development, considering the UNSC’s previous refusal to travel to the AU headquarters. The AU–UN Joint Task Force has convened and desk-to-desk meetings are regularly held. This shows a growing commitment to bring the organisations together structurally. There are also collaborative exercises taking place to look at the lessons the AU and UN can learn from political transitions – for example, in Mali and CAR – thus illustrating the intention of holding more joint or collaborative missions in the future.

We have also seen a growing collaboration in mediation processes – for example, in Sudan, where the AU is leading the mission with UN contributions, and in South Sudan, where the UN is leading the process with AU support. Over the past decade, the AU has built up its capacity to respond to crisis and support peace operations. In Mali and CAR, the AU was the first responder, and a UN mission followed. However, there are, of course, some challenges in this quest for better coordination. While the AU PSC member states recognise the primacy of the UNSC in matters of international peace and security, there is growing frustration about the perceived unwillingness of the UNSC to fulfil this duty. There is also frustration with the lack of financial support the AU receives from the UN for those tasks the AU is undertaking on behalf of the UNSC. The AU PSC feels that for the AU to be strong, the UNSC should not only authorise the AU to take responsibility for maintaining international peace and security in Africa, but the UN should properly resource the AU to do so.

A lack of predictable and sustainable financing has, in the past, been a major constraint for the AU in maintaining regional peace and security effectively, which is why the initiation of the levy is such a landmark decision. Earlier this year, the European Union’s (EU) decision to reroute funding of the AU mission in Somalia by 20% resulted in a near-crisis that the AU could not rectify. In CAR and Mali, meanwhile, the UN took over missions earlier than was desirable, because the AU and troop-contributing countries did not have the necessary resources to continue. In both cases, the UN missions ultimately lacked the same level of flexibility as their AU-led predecessors, which were able to undertake more offensive measures. The reality is that the AU can use more force in an offensive manner against armed groups in a conflict situation whereas the UN, according to the UN peacekeeping doctrine, cannot engage in force beyond self-defence. In both CAR and Mali, when the UN was deployed, the missions found themselves in a precarious situation where they could not intervene with enough force to secure the situation.20 These challenges could now be more avoidable, including at the mission start-up phase, because there is less reliance on voluntary donor contributions. Therefore, AU missions will be better able to meet the needs of conflicts and will be able to deploy for longer, regardless of the external contribution of funds.

Conclusion

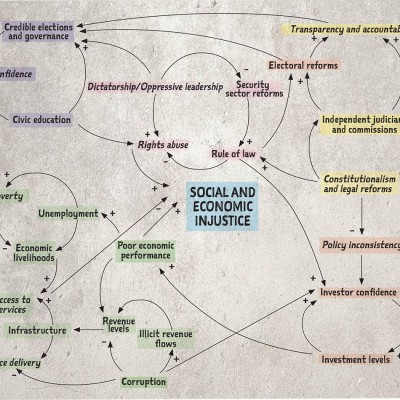

When the AU intervenes in a conflict in Africa, it shows solidarity within the continent, and that the organisation is taking responsibility for resolving problems on its own continent – that is, African solutions for African problems. These interventions are often closely coordinated with national governments, as well as the RECs. African peace operations are different to UN peacekeeping operations, but they should not be seen as inferior – rather as complementary to each other. The AU does peace enforcement; the UN does peacekeeping. However, the relationship between the organisations could be stronger, deeper and wider. As recent actions show, Africa wants to do more than just provide boots on the ground as part of this relationship. It wants a more balanced financial relationship, and this development within the AU Peace Fund takes the UN–AU partnership one step further. It is, however, only a subset of a number of larger strategic challenges for the relationship and the evolving notion of a global peace and security architecture. To reach a sufficiently strategic partnership, it is necessary to investigate a more clearly defined division of labour and burden-sharing arrangement that will enhance cooperation and efficiency, with the overall goal of providing the most effective responses to conflict. Progress on the financing side will, hopefully, act as a catalyst for this broader conversation. The next step for the two organisations will be to move beyond the narrow agenda of the number of troops and who pays for them to a much broader outlook of working together to resolve the political problems underlying Africa’s conflicts.

Endnotes

- Louw-Vaudran, Liesl (2016) ‘A New Financing Model for the AU: Will it Work?’, Institute for Security Studies, 25 July, Available at: <https://www.issafrica.org/iss-today/a-new-financing-model-for-the-au-will-it-work> [Accessed 10 August 2016].

- African Union (2015) ‘Decision on the Framework for a Renewed UN/AU Partnership on Africa’s Integration and Development Agenda [PAIDA] 2017-2027 Doc. EX.CL/913(XXVII)’, Assembly/AU/Dec.587(XXV), Available at: <>http://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/au/decision587-paida.pdf [Accessed 15 August 2016].

- African Union (2016) ‘Decision on the Domestication of the First Ten-year Implementation Plan of Agenda 2063 Doc. EX.CL/931(XXVIII)’, Assembly/AU/Draft/Dec.1-17(XXVI), Available at: <http://www.acdhrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Assembly-AU-Draft-Dec-1-17-XXVI-_E.pdf> [Accessed 15 August 2016].

- African Union (2016) ‘Summary of 27th AU Summit Decisions: Tax Imports to Finance AU; Establish Protocol to Issue African Passports to Citizens; and Extend Mandate of Chairperson and Commission’, Press Release Nº25/27th AU SUMMIT, Available at:< http://www.au.int/en/sites/default/files/pressreleases/31218-pr-pr_25_-_summary_of_27th_au_summit_decisions_-_tax_imports_to_finance_au_establish_protocol_to_issue_african_passports_to_citizens_and_mandate_of_chairperson_and_commiss.pdf> [Accessed 17 August 2016].

- Namata, Berna (2016) ‘States Adopt New Funding Model for AU’, Africa Review, 24 July, Available at: <http://www.africareview.com/news/States-adopt-new-funding-model-for-AU-/979180-3308464-9vl4k/index.html>[Accessed 15 August 2016].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- ECOWAS Vanguard (2012) ‘The ECOWAS Common External Tariff (CET) and Regional Integration’, Available at: <http://www.inter-reseaux.org/IMG/pdf/The_ECOWAS_CET_and_Regional_Integration_ECO_VANGUARD_Dec_2012_English_Edition_.pdf> [Accessed 15 August 2016].

- Murdock, Heather (2014) ‘Obasanjo’s AU Funding Proposal Rejected’, Business Day, 1 April, Available at: <http://www.bdlive.co.za/africa/africannews/2014/04/01/obasanjos-au-funding-proposal-rejected> [Accessed 1 August 2016].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Louw-Vaudran, Liesl (2016) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- International Peace Institute (2016) ‘Wane: Africans Want to Control Peace on Their Continent’, Available at: <https://www.ipinst.org/2016/05/au-un-strategic-partnership-for-peace-security [Accessed 30 July 2016].

- Ibid.

- De Coning, Cedric, Gelot, Linnèa and Karlsrud, John (2016) Towards an African Model of Peace Operations. In De Coning, Cedric, Gelot, Linnèa and Karlsrud, John (eds) The Future of African Peace Operations. UK: Zed Books.

- Ibid.

- Dersso, Solomon (2016) Stabilization Missions and Mandates in African Peace Operations: Implications for the ASF? In De Coning, Cedric, Gelot, Linnèa and Karlsrud, John (eds) op. cit. Also, Okeke, Jide Martyns (2016) United in Challenges: The African Standby Force and the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises. In De Coning, Cedric, Gelot, Linnèa and Karlsrud, John (eds) op. cit.

- International Peace Institute (2016) op. cit.

- De Coning, Cedric (2016) ‘Challenges and Priorities for Peace Operations Partnerships Between the UN and Regional Organizations – the African Union Example’, Challenges Forum Background Paper, Available at: <https://accord.org.za/publication/challenges-priorities-peace-operations-partnerships-un-regional-organizations/>[Accessed 15 August 2016].