Introduction

The security crisis in the Lake Chad Basin (LCB) region has been of great concern since its turning point in 2009 due to the expansion of Boko Haram (BH) as one of the deadliest terrorist groups in the continent. This crisis is characterised by complex causes, including a development deficit, the lack of a social contract between the state and the population, weak governance structures, and a consequent violent extremist insurgency that has emerged and grown from and within the instability. While the efforts of those tasked to fight against the spread of these threats are numerous and commendable, much still needs to be done to ensure a safe and secure environment for all populations in the region.

Through kinetic operations and non-kinetic interventions, the four governments of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, with the support of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), the African Union (AU), United Nations (UN) agencies, and other critical partners have scaled up their interventions in the region. The scaled-up interventions include the Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) processes as part of the Regional Strategy for the Stabilisation, Recovery and Resilience (RS-SRR) of the Boko Haram-affected areas. However, it is common knowledge that these four countries are faced with challenges in the handling and treatment of individuals associated with BH – and other affiliated groups – when they surrender or exit these groups. First and foremost, these challenges include the lack of pre-conditions for traditional DDR to take place. A further challenge is the proliferation of arms and ammunition in the region among the civilian population due to a lack of security and safety provision.

Since 2021, the Lake Chad Basin countries, especially Nigeria as the epicentre of the crisis, have been affected by the mass defection of approximately 90 000 individuals from BH and other groups.1Onuoha, Freedom; Tchie, Andrew; and Llorens, Mariana (2023) ‘A quest to win the hearts and minds: Assessing the Effectiveness of the Multinational Joint Task Force’, EPON, Available at: <https://effectivepeaceops.net/publication/mnjtf > [Date accessed: 30 September 2022] This has put an enormous amount of pressure on the already over-stretched and weak infrastructure available to deal with the defectors. In addition, civilians have increasingly armed themselves to protect their communities in cases where the military or stabilisation efforts may not reach. This has led to the establishment of many different vigilante groups and self-defence committees across the region. What may appear to be a short-term solution – as many of them prove to be effective security mechanisms – may actually have adverse implications for the prospects of peace and security in the region.

BH ex-associates are disengaging from terrorist affiliation and returning to what may be insecure or at least unstable environments where they could be exposed to recidivism or re-radicalisation rather than to safe, peaceful and effective reintegration processes. This creates a security dilemma in the region impacting the prospect of achieving long-term stability and the sustainability and durability of reintegration processes within DDR.

Conceptualising DDR in the Lake Chad Basin

Disarmament refers to the collection, documentation and tracking of all small arms, ammunition, explosives and light and heavy weapons used by combatants, and the management of these arms afterwards. Demobilisation refers to the removal of combatants from an armed group, their insertion into temporary centres designated for this purpose, and the support packages provided for their subsequent reinsertion and reintegration. Reintegration refers to the more long-term socioeconomic process in which ex-combatants eventually obtain civilian status and are given sustainable employment and income opportunities that allow them to reintegrate into communities.2UNDP (2012) ‘UNDP Practice Note: Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration of Ex-combatants’, Available at: <https://www.undp.org/publications/practice-note-disarmament-demobilization-and-reintegration-ex-combatants > [Date acccessed: 10 October 2023]

The DDR of ex-combatants or ex-associates of a specific violent group is a very complex process with many political, military and humanitarian dimensions. Therefore, it cannot be addressed in isolation. Its objectives are to address the challenges of the socioeconomic situation of ex-combatants and the risks they pose to peace and security, and to ensure that their reintegration is eventually translated into a contribution to peace and stability.

However, DDR has significantly evolved over the decades, and many emerging factors have affected how DDR is understood, designed and delivered. Given the evolving nature of current conflicts, DDR per se is no longer used or implemented in its strict sense. This results in fewer political or peace settlements as solutions to conflict, an increase in violence by non-state actors, a rise in terrorist activity, and a regionalisation of conflict resulting in the fragmentation of responses by the different states and actors involved. In fact, the definitions provided above correspond with the first generation of DDR or the notion of traditional DDR. The second generation of DDR includes situations with numerous belligerents and where it is challenging to establish a peace process. The third generation of DDR is faced with insurgency and violent extremism during ongoing conflict and differs from the second generation in that there is a lack of a peace settlement.3Hoinathy, Remadji; Samuel, Malik; and Olojo, Akinola (2023) ‘Managing exits from violent extremist groups: lessons from the Lake Chad Basin’, Institute for Security Studies, Available at: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/policy-brief-173.pdf> [Date acccessed: 10 October 2023]

DDR in the LCB

With the support of the AU, the UN Development Programme (UNDP), and the MNJTF Troop-Contributing Countries (TCCs), the LCBC adopted the RS-SRR to guide the transition from a purely counter-terrorism mission to one with a more stabilisation and development-oriented approach. As an overarching strategy that aims to address the different deep-rooted causes of conflict and under-development in the LCB, the RS-SRR is organised into nine pillars of intervention. Pillar Three is the Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation, Reinsertion and Reintegration of Persons associated with BH. Drawing on the case of the LCB region, this article looks at the third generation of DDR, where the violence is characterised by an ongoing insurgency-like conflict. As mentioned above, the third-generation DDR differs from traditional DDR, which has been defined by the UN as accompanied by a peace agreement, amnesty or cessation of hostilities.4UNDP (2019) ‘Operational Guide to the Integrated Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration Standards (IDDRS)’, Available at: <https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/operational-guide-rev-2010-web.pdf > [Date acccessed: 10 October 2023]

It has been reported that most BH defectors surrender and leave their weapons behind due to fear of being re-captured or killed. The need for disarmament of ex-associates is not necessary in this context. As hostilities in the LCB persist, Member States and stakeholders must develop context-specific approaches that are suitable to the specific needs of each affected area.

UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1373 stresses the need for accountability and to bring terrorists to justice. UNSC Resolution 2178 included this as part of a broader approach by proposing prosecution, rehabilitation and reintegration strategies for returning foreign terrorist fighters. Moreover, UNSC Resolution 2396 elaborated on the need to assess and investigate suspected terrorists, develop and implement comprehensive risk assessments for these individuals, and take appropriate action, including by considering appropriate prosecution, rehabilitation and reintegration measures in compliance with domestic and international law.5UNSC (2001) ‘UNSC Resolution 1373, Chapter VII’; UNSC (2014) ‘UNSC Resolution 2178, Chapter VII’; UNSC (2017) ‘UNSC Resolution 2396, Chapter VII’. As a consequence, the governments of the LCB, together with the RS-SRR and its support partners, developed a Screening, Prosecution, Rehabilitation and Reintegration (SPRR) approach that is context-specific and common to the region. The SPRR was also developed in line with international standards for the handling of BH ex-associates.

Challenges and implications of the SPRR in the LCB

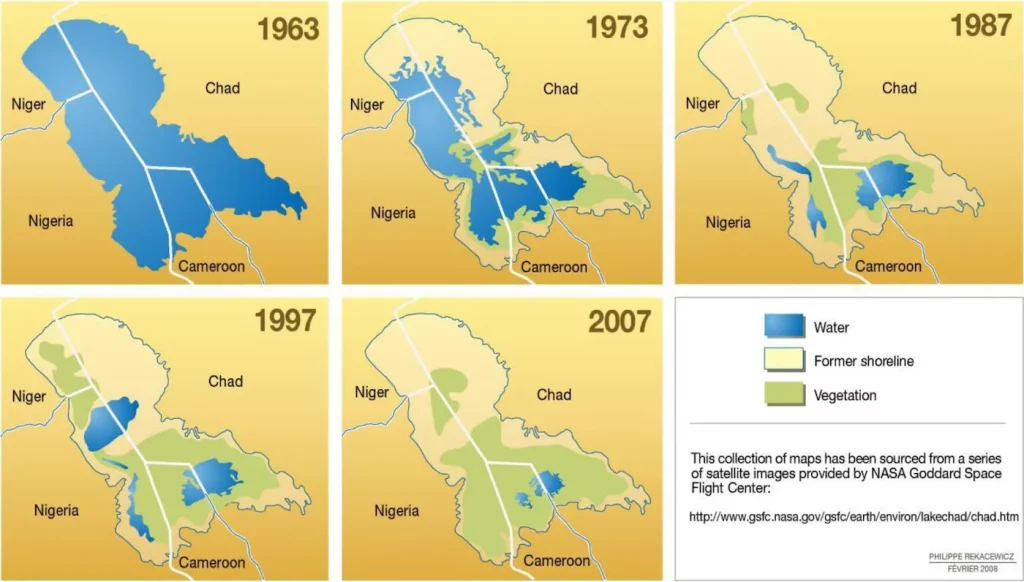

The LCB is troubled by a development deficit, weak governance structures in some areas, and the catastrophic consequences of climate change, which are some of the main causes of instability and precursors of terrorist activity. In addition, while the development of enhanced mechanisms to implement SPRR in the region is gaining traction, there are a number of issues that render the implementation of SPRR difficult. These include financial constraints and the lack of institutionalised responses, police capacity, physical security provision, appropriate resources and infrastructure to conduct all the activities in SPRR.

An additional concerning challenge is the possession of arms by civilians. Illicit trafficking and arms proliferation in the region and among civilian communities may be caused by the leaking of national arms stockpiles during conflict, circulation and trafficking of arms from past and ongoing neighbouring conflicts, or the tradition of craft arms production typical of the region. Civilian possession of arms in the LCB is manifested in two ways: through customary practice, as some civilians possess and craft weapons which might be culturally common and accepted in some areas and communities,6With a license, it is possible to own firearms legally in the four countries of the LCB. For example, by 2018, Niger granted 2 000 licenses, and in 2021, Cameroon granted 3 800 licenses. and through the more formalised or ‘institutionalised’ way seen in the establishment of vigilante groups or self-defence committees. In some cases, these groups collaborate with the authorities and security forces and may generally be seen as allies of the state, or they do not necessarily seek to challenge it. Therefore, they are viewed as a relatively positive security output. For example, in Cameroon, the decline in attacks in 2021 was partly attributed to the involvement of the Comité de Vigilance (COVI).7UNDP (2021) ‘Conflict Analysis in the Lake Chad Basin 2020-2021: Trends, developments and implications for peace and stability’, Available at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-08/Conflict%20Analysis%20in%20the%20Lake%20Chad%20Basin.pdf> [Date acccessed: 19 September 2023] This may have been a positive short-term solution to insecurity in some cases, but not all. It is not necessarily an effective security mechanism that fills the vacuum left by the lack of provision of formal protection. In the long term, the existence, rationale and functioning of vigilante groups can have adverse effects on the prospect of peace and security and the overall successful conduct of SPRR.8There have been confrontations between the Civilian Joint Task Force and military or police forces in Nigeria and some have been accused of other crimes, such as drug dealing, extortion and robbery. International Centre for Investigative Reporting (2015) ‘Civilian JTF: The Making Of A Human Time Bomb’, Available at: <https://www.icirnigeria.org/civilian-jtf-the-making-of-a-human-time-bomb> [Date acccessed: 31 October 2023]

A security dilemma

The possession of arms by the civilian population and the existence of vigilante groups in the LCB pose a risk to the achievement of long-term stability and challenges to the effective overall implementation of SPRR. The existence of vigilante groups underlines the fact that states are not able to provide sufficient security or other protection services on their own. While they seem to interfere in the strained relationship between the security forces and civilians, paradoxically, they create a parallel security system that challenges the legitimacy of the state, ultimately hampering any effort to reestablish stability and the social contract between the state and the population. Vigilante groups may also exacerbate conflict as dividers of communities and instigators of community violence. The lack of accountability and regulatory measures over vigilantism has resulted in violence against civilians, human rights violations, extortion, and even killings.9Agbiboa, Daniel and Aniekwe, Chika (2023) ‘Understanding and Managing Vigilante Groups in the Lake Chad Basin Region’, UNDP report, Available at: <https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-03/Understanding%20Vigilante%20Groups.pdf> [Date acccessed: 31 October 2023]

Similarly, the widespread possession of arms among civilians without effective regulation and management complicates the security dynamics in the region, increases the risk of escalation of violence, and motivates further illicit trafficking of arms and organised crime. As the region confronts these many challenges, the overall effectiveness of SPRR is jeopardised. On the one hand, the availability of arms among civilians increases the likelihood of BH members or ex-associates accessing weapons for their re-engagement, rendering the initial stages of SPRR inconclusive. On the other hand, it impacts the rehabilitation and reintegration stages. Successful reintegration relies on stable, secure and regulated environments. Vigilante groups or armed civilians can only add more layers of complexity that hinder the peaceful reintegration of BH ex-associates and, therefore, render SPRR less effective.

In addition, vigilantism or possession of arms by civilians could create conditions for the recidivism or re-radicalisation of BH ex-associates, creating a vicious circle in the SPRR process. While ex-associates may disengage and be demobilised, they may also be returning to communities where conditions exist that motivate their return to violence. Due to challenges faced during the rehabilitation and reintegration stages of SPRR, such as financial and capacity constraints or the lack of sensitisation among welcoming communities, there is a higher risk for ex-associates not to rehabilitate or be fully welcomed by their host communities. In cases where they may face rejection or marginalisation by their communities, the likelihood of an ex-associate choosing to return to violence is higher, especially in environments where there is armed resistance and weapons are available.

Furthermore, despite the many efforts to address the root causes of instability, insecurity remains in the region, and basic needs are not covered for most affected populations. In Niger, for example, 30% of ex-associates believe their lives were better when they were associated with the group.10Huvé, Sophie; O’Neil, Siobhan; Hoinathy, Remadji; and Van Broeckhoven, Kato (2022) ‘Preventing Recruitment and Ensuring Effective Reintegration Efforts: Evidence from Across the Lake Chad Basin to Inform Policy and Practice’, UN Institute for Disarmament Research, Available at: <https://unidir.org/publication/preventing-recruitment-and-ensuring-effective-reintegration-efforts-evidence-from-across-the-lake-chad-basin-to-inform-policy-and-practice> [Date acccessed: 31 October 2023] This indicates that the reasons why they initially joined could motivate a return to violence or criminality. Reintegrating into an armed environment further encourages this.

One must investigate why an ex-associate left BH. For instance, saying they had a change of heart is the easiest or most risk-free way to escape and get the support provided by the authorities. However, they could be leaving for reasons such as being expelled after a political debate. Therefore, no change of heart or willingness to renounce violence occurred. They may be gathering financial support or intelligence and wanting to recruit more combatants – vigilantes or armed civilians are candidates as they possess some expertise in weapon-handling. Lastly, the possession of arms in a community may be a result and a cause of further illicit trafficking and organised crime.

The interplay between the existence of vigilante groups and the possession of arms by civilians, constrained reintegration initiatives, and a weakened governance structure underscores the security dilemma that exists when handling the exit of BH ex-associates in the LCB. What appears to be a solution to a security vacuum, may have adverse consequences, render SPRR counterproductive, and impede any prospect for long-term stability. Therefore, while the focus during SPRR is generally placed on ex-associates, it should also be placed on the wider community and the conditions under which ex-associates are meant to reintegrate.

Moving forward

The crisis in the LCB is characterised by a number of interlinked factors that cannot be resolved in isolation and must be addressed through comprehensive, overarching and connected approaches. If an approach is not implemented or is not effectively functioning, other approaches may be affected, creating a vicious circle of insecurity. For example, even if the MNJTF does a commendable job in neutralising terrorists, but communities are not being sensitised to welcome ex-combatants back, the latter may have a further pretext for returning to terrorist groups.

In an ongoing insurgency conflict like that of the LCB region with no cessation of hostilities, a third generation of DDR is conducted through the SPRR approach taken by the LCBC states. The focus of the third-generation DDR is on documenting the mass exit of defectors, profiling and prosecuting those involved in violent groups, and ensuring their rehabilitation and reintegration into communities. SPRR also involves the prevention of further recruitment and the reactivation of conflict instigators; however, it faces many challenges to its successful implementation. The existence of vigilantism and the possession of arms by civilians in certain areas of the region are two factors that serve as obstacles to the successful implementation of SPRR and the prospect of peace and security. As defectors disengage from violent groups, they return to communities where armed resistance could instigate their recidivism and further instability. Therefore, the security dilemma posed by vigilantism and arms possession by civilians calls for a holistic approach with comprehensive and adaptive responses at both policy and operational levels. These responses must include enhanced and improved initiatives to address the root causes of instability, the proliferation and illicit flow of arms in the region, and the unregulated activities of certain vigilante groups. DDR must be a multidimensional and overarching process that considers all factors and constraints simultaneously and connects all stakeholders. Thus, this article proposes the following actionable recommendations for current and future policy and programming stakeholders:

- Noting the UN’s Integrated DDR Standards (IDDRS), a number of targeted measures can be combined with the main components of SPRR. DDR-related tools refer to measures that help reduce levels of violence and the transition of ex-associates to peaceful civilian life. These include weapons and ammunition management (WAM) and community violence reduction (CVR) activities. Thus, in the LCB, while SPRR programmes are conducted, these DDR-related tools can and should be simultaneously employed to ensure the focus is extended to curbing violence and disarming the wider community. For this, SPRR practitioners, CVR stakeholders and WAM experts must work in much closer cooperation to ensure more effective and productive outcomes. In addition, the private sector can support states in the delivery of technological solutions for the search, control and management of arms and of borders through which arms trafficking takes place.

- The cross-border nature of the conflict in the LCB calls for the creation of a regional information-sharing loop with other institutions, such as the G5 Sahel, Accra Initiative, Liptako Gourma Authority, Nouakchott Process, and the AU. The AU should use its political convening power and play a role in facilitating this to address the proliferation and illicit flow of arms in a more cohesive and systematic way. The AU could also convene WAM experts and DDR practitioners from other regions to share lessons learned that can be applied to the LCB context.

- Since the emergence of vigilante groups is a by-product of the security vacuum left by the lack of formal security provision, the LCB governments should invest in the capacity building of policing structures and in undertaking Security Sector Reform (SSR). This would allow vigilante groups to become a more positive security output by restricting their operations to assisting the military and police forces with screening and profiling BH ex-associates, intelligence gathering, daily patrolling, and community mediation.

- The LCB governments should establish more robust regulations and oversight mechanisms that regulate the operations and activities of vigilante groups, including the investigation of human rights violations and enforceable accountability for such violations.

Mariana Llorens Zabala is a Junior Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). She works for the Training for Peace (TfP) Programme and has been conducting research on African-led peace support operations and counter-terrorism on the African continent since December 2021.