Introduction

It was not long ago that the decline of coups was being celebrated, not just in Africa, but globally. New African magazine asked in Fall 2015 why coups are going out of style.[1] Writing in September 2017, Schiel and her co-authors pointed to a two-year period since the last attempted coup in Africa, with the continent approaching three full years since the last successful attempt.[2] A month later, former Malian Foreign Minister Kamisssa Camara – even in the context of herself serving shortly after a coup –suggested that ‘the time for coups is over’.[3] Though perhaps not a long period at first glance, this was the longest coup-less stretch in Africa since decolonisation. Various efforts have been made to explain this shift, including the institutionalisation of more open political systems and the role of external actors such as the African Union (AU).[4] Though the November 2017 coup against Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe was a new coup, coups remained something of an afterthought in subsequent years.

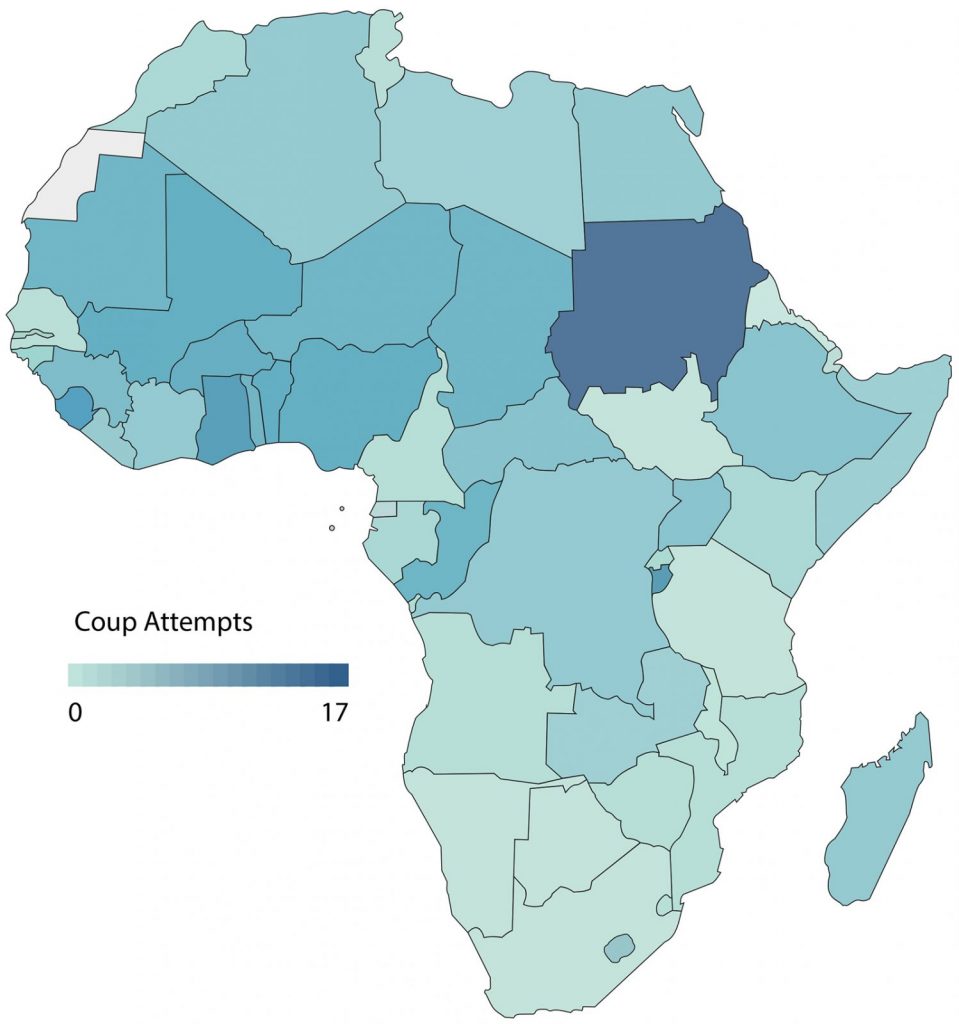

More recently, commentary at the Council on Foreign Relations concluded that ‘old style’ coups in which soldiers attempted to seize power had been supplanted by incumbents scheming to maintain it.[5] This has changed since August 2020, with successful coups taking place in Chad, Guinea, and twice in Mali as well as a failed effort to seize power in Niger, and both a failed and successful coup in Sudan. This apparent resurgence in the phenomenon has prompted much discussion on the causes of these events, whether they are related, and what – if anything – the region can do to buck the trend. Independent African states have experienced over 200 coup attempts since 1950, of which over 100 have succeeded (see Figure 1).[6]

Figure 1: Coup Attempts in Africa since 1950[7]

This article reviews the recent ‘coup epidemic’ within a larger historical context, reflecting on commonalities, disparities, and how these events fit into international frameworks designed to deter coups. The region’s recent coups point to two important challenges to the AU framework on Unconstitutional Changes of Government (UCG). First, though the AU had been heralded for becoming less tolerant of military coups, the organisation has been less responsive to the unconstitutional maintenance of power. As the continent witnesses an increased willingness of leaders to flout the institutions that allowed them to come into power, the accompanying loss of popular legitimacy has either directly motivated or provided surface legitimacy for coups against what are seen as increasingly dictatorial incumbents. Second, recent years have seen acquiescence to military coups that at times is more in line with the AU’s predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Though post-coup responses might be seen as having little to do with the cause of any specific coup, we argue that these responses provide important cues to future plotters. Since the international community demonstrates an unwillingness or inability to visit sufficient costs upon coup-born regimes, the international community will continue to lose its ability to deter coups.

The Coup Epidemic of 2021

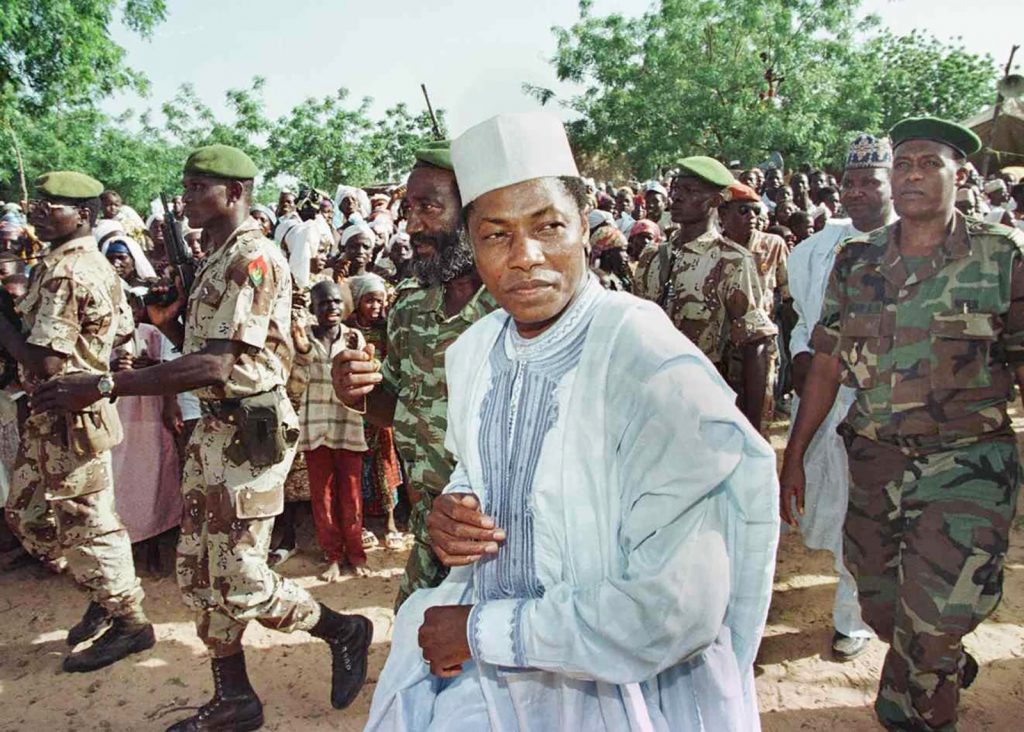

Attention to coups shifted to southeast Asia following Myanmar’s 1 February 2021 coup against its young democracy. This attention returned to Africa following a short-lived coup effort from elements of the Nigerien air force on 31 March 2021. Three weeks later, Chad’s military installed General Mahamat Idriss Déby following the death of his father, President Idriss Déby. A power vacuum was created after the latter became the first head of state to be killed in Africa in battle since Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia fell to Mahdist forces in March 1889. Mali soon saw interim President Bah N’Daw removed on 21 May 2021, just eight months after the country’s previous coup. Guinea’s Alpha Conde was the next victim, with his 5 September 2021 ousting. Though the next coup attempt failed in Sudan on 21 September 2021, the armed forces successfully removed Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok on 25 October 2021.

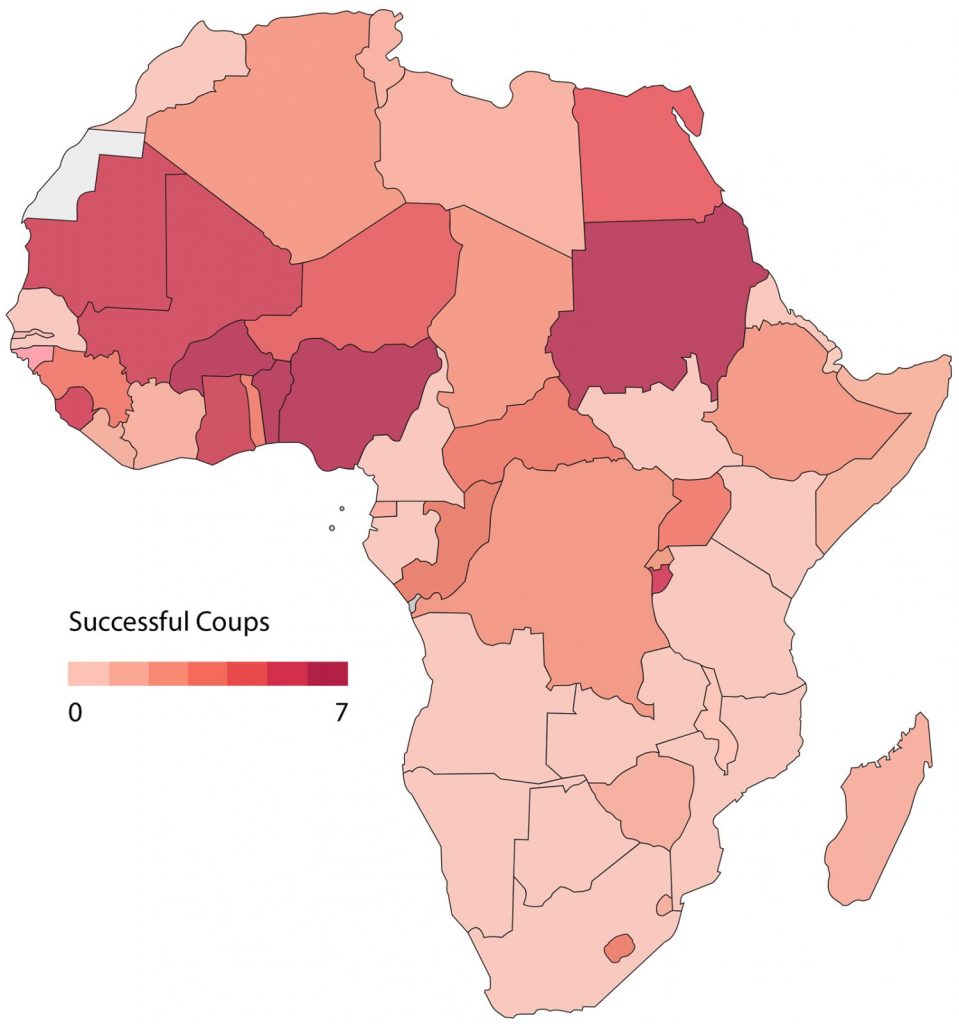

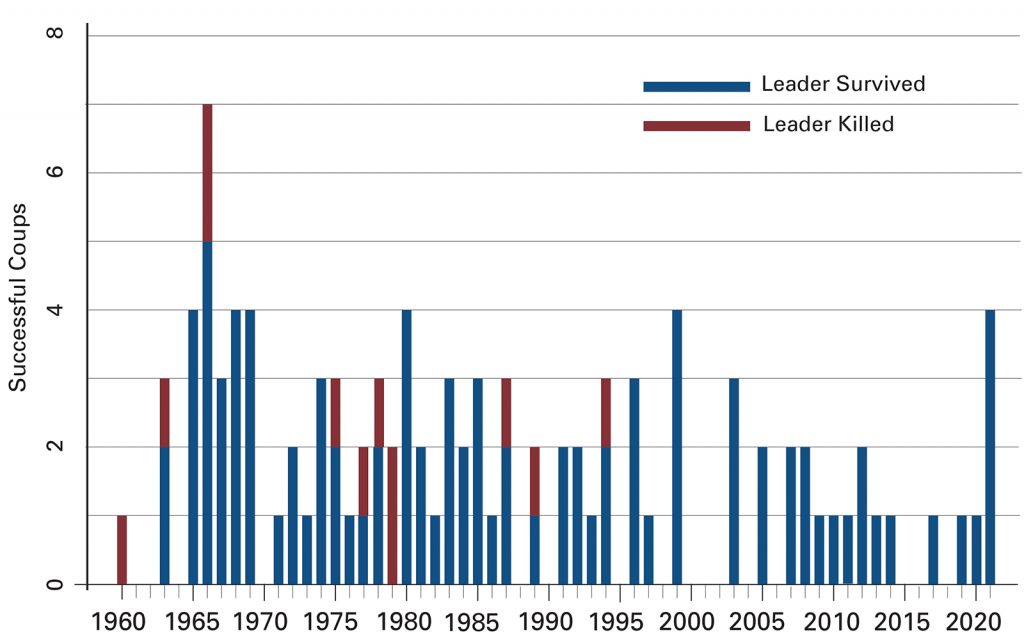

Figure 2: Successful and Failed Coups in Africa Over Time

As difficult as it would be to overstate the seriousness of Africa’s coup resurgence, some observers have managed the task. Following Sudan’s October coup, The Wall Street Journal declared military coups to be at their highest level since the end of colonialism.[8] Though hyperbolic, 2021’s departure from recent history has been dramatic enough to earn comparison with the independence era. The Economist more accurately noted that 2021 has seen more coups than the previous five years combined.[9] Our exploration of the data indicates that the year has seen the most successful coups in Africa since 1999 and the most total coup attempts since 1991. Perhaps more importantly, the coups have not fallen into any particular pattern with regard to victims. They have occurred within the context of leadership vacuums, young regimes and long-entrenched ones, countries moving both toward and away from democracy, those with ongoing insurgencies, and those in relative peace. It is perhaps more intriguing that this high number of coups in 2021 occurred within the context of the AU UCG framework, that since 1997 has sought to discourage coups and other illegal seizures of power.

Growth of the Anti-Coup Norm?

With the loss of foreign patrons and sweeping challenges in Africa, such as structural adjustments and unprecedented pressure for democracy, the immediate post-Cold War period saw a spike in coup attempts. Soon, however, the region began moving toward a more formal anti-coup framework. In 1997, Robert Mugabe declared, ‘We are getting tougher and tougher on coups […]. Coup-plotters […] will find it more difficult to get recognition from us. […] we now have a definite attitude against coups’.[10] Mugabe’s words came in the midst of the OAU Summit in Harare, during which Nigerian forces under the auspices of the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) commenced a bombardment meant to dislodge Johnny Paul Koroma’s recently established junta in Sierra Leone.

Mugabe’s remarks were followed by the 1999 Algiers Summit decision on UCG.[11] This decision urged the restoration of constitutional rule in those countries that had experienced illegal power seizures since the Harare Summit and called on the OAU Secretary-General to facilitate constitutional governance in Member States. The 2000 Lomé Declaration on the Framework for an OAU Response to UCG went even further by defining what actions constituted UCG and stipulating the OAU’s responses to such illegal power seizures.[12] In the Lomé Declaration, UCGs included coups against democratically elected governments, power seizures by mercenaries, armed rebels, and dissident groups, and incumbents’ refusal to relinquish power following electoral defeat. Additionally, the Lomé Declaration outlined two responses from the OAU Central Organ in the event of a UCG:

- Condemnation of the act, suspension of participation in OAU decision-making, and a six-month deadline to restore constitutional rule.

- The OAU Secretary-General’s use of diplomatic pressure and coordination with Member States, regional organisations, and other international actors to facilitate the restoration of constitutional rule. Further pressure, in the form of targeted sanctions, visa restrictions, limited diplomatic contacts, and trade embargoes, was to be deployed in those instances where the illegal regime was not making progress towards a return to constitutional rule.[13]

The Lomé Declaration continues to inform the AU policy on UCG. For instance, the 2002 Constitutive Act of the AU and the protocol establishing the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) confirmed the Lomé Declaration as its formal document on dealing with illegal power seizures, reiterating that governments acquiring power through illegal means would be suspended from participating in the AU and could face further sanctions. The provisions of the Lomé Declaration were further strengthened through the 2007 African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (Addis Ababa Charter).[14] This charter, which entered into force in 2012, makes three notable amendments to the Lomé Declaration. First, the charter includes attempts to amend or revise constitutions to extend one’s rule as UCG. Second, the charter authorises the AU PSC to respond to UCG events. And third, the charter stipulates that those who obtain power through unconstitutional means should not participate in or contest the elections aimed at restoring constitutional rule.

Academic commentaries on international conflict indicate that deterrence occurs when actors ‘define the behavior that is unacceptable [and] publicize the commitment to punish and restrain transgressors’.[15] While the OAU may have taken steps in Harare and Lomé toward the former, it was not until the abandonment of the non-intervention norm and the launch of the AU that the latter could be established. Even then, efforts to ‘define’ and ‘publicize’ an anti-coup policy might have been meaningless in the absence of demonstrating a commitment to the framework. Just months after the Lomé meeting, for example, General Robert Guei was allowed to represent Cote d’Ivoire following his coup against President Henri Konan Bedie. While the early years saw some inconsistencies in response, the establishment of the AU PSC represented an important shift toward invariably condemning coups.[16] At the time of Souaré’s seminal study on the AU as a ‘norm entrepreneur’ on military coups d’état in Africa, every coup between 2004 and 2012 saw the regimes suspended from the AU, with half witnessing the ensuing junta being forced from power.[17] It was within this context that coup attempts dropped by nearly 60% from pre-AU levels, and nearly 50% from the post-Cold War period immediately preceding the AU.[18]

Decline of the Anti-Coup Norm?

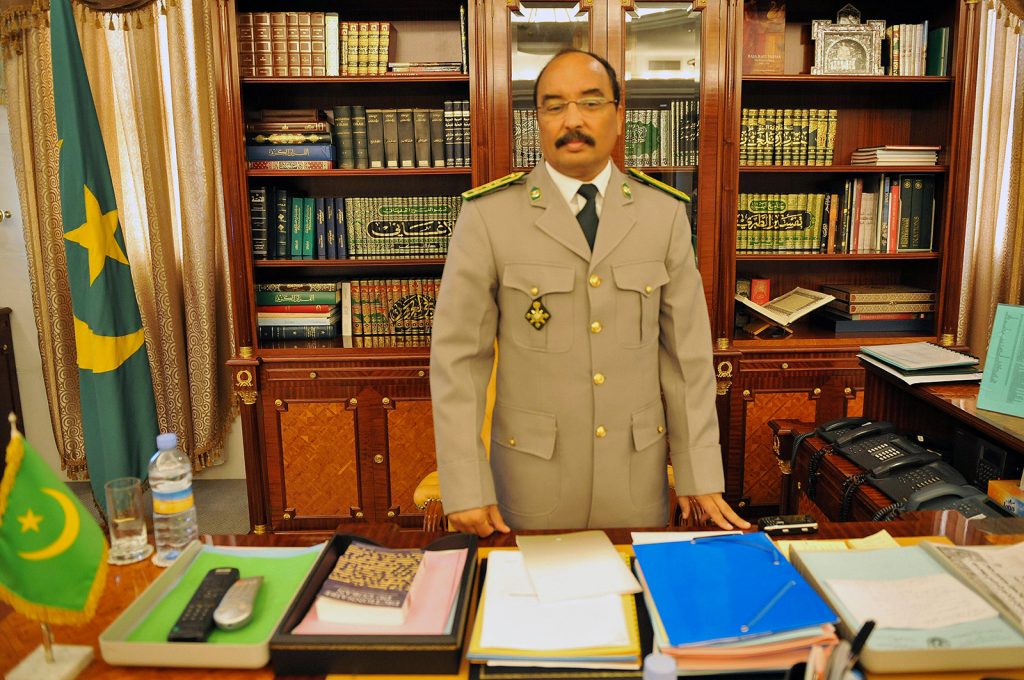

Closer inspection reveals a mixed record in the AU’s implementation of its UCG policy, particularly towards coups. Following the 2008 coup in Mauritania led by General Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, the AU suspended Mauritania and later imposed sanctions on the coup-born regime.[19] Subsequent to an agreement being reached to facilitate a transition to constitutional rule in 2009, the AU lifted Mauritania’s suspension and sanctions and accepted Abdel Aziz as the new democratically elected leader, despite his participation in the 2008 coup.[20] Similarly, despite labelling Abdel Fatah el Sisi’s takeover in Egypt in 2013 as a coup and suspending Egypt from the organisation, the AU nonetheless accepted Sisi’s election as president in 2014 and lifted Egypt’s suspension, contrary to the Addis Ababa Charter.[21] The AU quickly described the Burkinabe armed force’s seizure of power in the vacuum created by President Blaise Compaoré’s resignation in 2014 as ‘constituting a coup’.[22] However, the organisation baulked at following through on its threats of suspension and sanctions, even after Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Zida – who had illegally assumed power – was formally announced as Prime Minister of the transitional government.[23] The Burkina Faso case required the PSC to balance the unconstitutional seizure of power with the fact that Compaoré’s resignation was the product of a ‘people’s right to overthrow oppressive regimes’.[24] Though also targeting an oppressive regime, the coup against Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe in 2017 was hardly an effort by or on behalf of ‘the people’, and instead represented a clear effort to preserve the privileges of the armed forces and their allies. Instead of suspending the new government or even acknowledging that a coup had taken place, actors, including the AU and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), accepted Mugabe’s exit as a resignation and ‘tacitly’ endorsed the coup.[25]

More recently, Chad’s 2021 coup demonstrated a clear break from a directly comparable case: Togo’s 2005 coup. After 36 years in power, Togolese President Gnassingbé Eyadéma died in office after suffering a heart attack in February 2005. Constitutionally, the head of the National Assembly should have succeeded Eyadéma, but the military appointed Eyadéma’s son, Faure Gnassingbé, as the new president. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and other relevant actors strongly condemned the coup, imposing a travel ban on coup leaders, freezing their assets, establishing an arms embargo, and enacting a diplomatic suspension, all of which would be lifted only if constitutional order was restored. Following a post hoc effort to amend the constitution to accept the manoeuvre, ECOWAS further demanded a reversal of efforts to legitimate the coup.[26] The AU suspended Togo’s membership, endorsed the sanctions imposed by ECOWAS, and threatened further sanctions, if deemed necessary, on ‘de facto authorities’ in the country.[27] Following the lead of these regional actors, the United States terminated military assistance and supported the sanctions imposed by ECOWAS until Togo conformed with ECOWAS’s communiqué sent on 9 February 2021.[28]

In stark contrast, the instalment of President Idriss Déby’s son in Chad in April 2021 saw a complete reluctance to describe the event as a coup or as falling under the UCG framework. This reaction was viewed as illustrating an ‘erosion of the AU consensus on unconstitutional changes of government’.[29]

International Cues and the Future of the Coup in Africa

Africa was celebrated for turning the tide against coups, and a major part of that effort was attributed to the actions of the international community. Whatever anti-coup norm had been established, however, appears to have weakened. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has referred to the problem as a current ‘epidemic of coup d’etats’.[30] The context of the pandemic emphasises the importance of efforts to mitigate the further spread of Covid-19. While individuals might implement social distancing and hygiene practices, the actions of outsiders are also important. Secretary-General Guterres pointed to the need for the international community – particularly ‘big powers’ – to guarantee ‘effective deterrence’ against coups. Any prior effective deterrent, accounting to Guterres, has been undermined by the Covid-19 pandemic. With an ineffective Security Council and the financial stresses of the pandemic, Guterres argues we are now in ‘an environment in which some military leaders feel that they have total impunity, they can do whatever they want because nothing will happen to them’.[31]

The danger of a lack of deterrent lies not in an inability to reverse coups that have already occurred, but rather in preventing future coups by unequivocally demonstrating that they will not be tolerated. Every successful coup that fails to see such a signal will contribute to a weakening of the norm. Would be coupists not only will be more willing to act on their schemes, but the continent could soon see more serious post-coup effects. Recent studies pointing to the ability of the international community to promote post-coup democratic transitions, for example, rely on the assumption that coup leaders are more likely to return to the barracks and allow transitions specifically because of the costs associated with trying to retain power.[32] Though perhaps at first seeming counterintuitive, a growing number of studies have suggested that coups against dictators can roughly double the likelihood of a democratic transition.[33]Even a sceptical assessment of this ‘democratic coup’ thesis reported that around 40% of post-Cold War coups have been followed by a democratic transition. To be clear, each of these studies notes that democracy remains a difficult prospect in post-coup environments. To the degree that democracy is possible, however, these studies are in agreement that transitions are largely the product of international pressure.

A robust anti-coup norm might be unable to deter all coups. However, those that occur in this context are significantly more likely to see a return or transition to civilian rule. A weakening of the norm could mean an increased likelihood of officers such as Colonel Zida attempting to maintain power or eventually heads of state such as Abdel Fattah al-Sisi dropping any pretence of a return to civilian rule. Simply put, the lack of a deterrent consequently translates into an increased likelihood of renewed or worsened authoritarianism, and potentially even military rule.

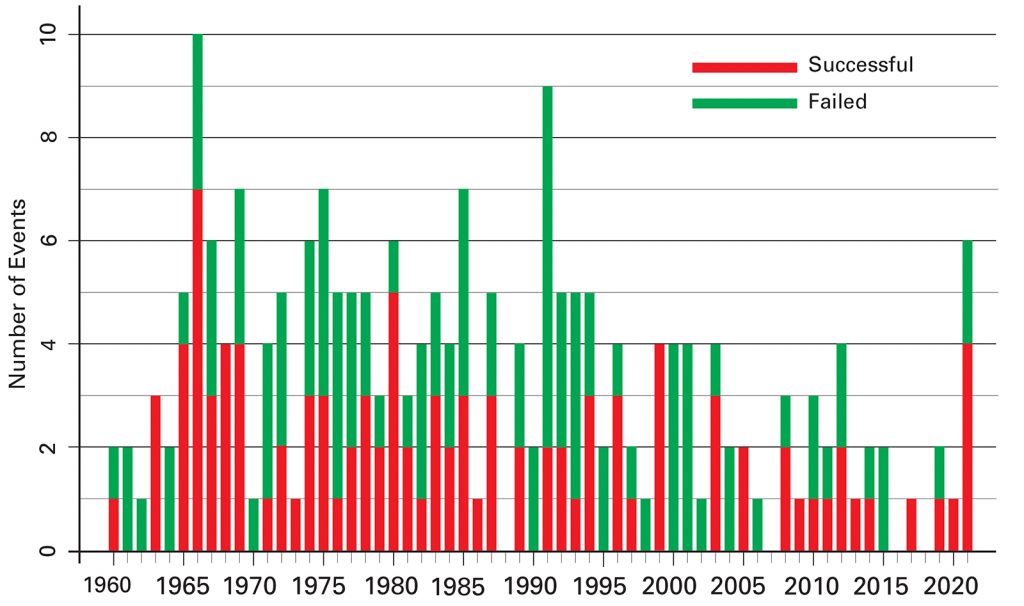

Figure 3: Decline in Leader Deaths via Coups Over Time[34]

A lack of restraint could also translate into more sinister coup practices. Though the phenomenon has – to our knowledge – not been empirically investigated, the growth of the anti-coup norm was accompanied by improved outcomes for executives who were removed from power. Fourteen African leaders have been killed during, or in, the immediate aftermath of coups since 1960. None, however, have been killed in a coup since the assassination of IIbrahim Baré Maïnassara during Niger’s 1999 coup.[35] In fact, leader fate closely parallels international developments. Twelve of the 67 (18%) successful Cold War coups saw the leader killed.[36] The post-Cold War, pre-AU era (1990-2001) saw two leaders killed in 16 coups (12.5%). Under the AU (2002-2021), however, no leaders were killed in the 21 successful coups witnessed on the continent. The current 24 consecutive coups without a leader death is easily the longest streak the continent has seen. Not only did the growth of the anti-coup norm decrease coups, when coups still occurred, they may have been executed with more restraint.

Conclusion

Compared to other continental organisations, the AU stands out as having a framework against UCG that guides African states in their responses to coups. However, the resurgence of coups in 2021 highlights gaps in the AU framework, particularly the extent to which the AU consistently reacts to coups and other illegal power seizures and its ability to influence coup-born regimes, and in the process, discourage others from orchestrating such power grabs. To strengthen its framework, it is perhaps time for the AU to implement its UCG policy fully beyond coup events. Had the AU implemented its UCG policy against Ibrahim Boubacar Keita of Mali for attempting to extend his rule, the 2020 coup would probably not have taken place, and a stronger signal would have been sent to leaders seeking to remove term limits. Responding to ECOWAS’s decision to suspend Guinea following the coup against Alpha Conde, Liberian president George Weah noted, ‘While we are condemning these military coups, we must also muster the courage to look into what is triggering these unconstitutional takeovers. Could it be that we are not honouring our political commitments to respect the term limits of our various constitutions?’[37] It is time for the AU to pay closer attention to this growing threat to constitutional rule in Africa.

Additionally, the ability of the AU to pressure coup-born regimes hinges on the extent to which it can influence other actors with closer ties to the affected state. Although the AU UCG framework includes a set of punitive measures, these perhaps may not be sufficient to compel coupists to relinquish power. The AU does urge coordination and cooperation with other relevant actors in responding to coups. Yet, the extent to which such collaboration takes place remains unclear. Suspension from the AU is punitive, although it is doubtful how much damage this does to the suspended state, especially if it continues to maintain its other relations with other states. Similarly, sanctions, visa bans, and the freezing of assets may hurt, but this depends on the degree to which the coupists are linked to other states in Africa. Enhanced collaboration, both formal and informal, between the AU and those actors that have closer relations with the coup-afflicted state can be a more effective means of pressuring coup-born regimes to relinquish power.

Dr Jonathan Powell is an Associate Professor in the School of Politics, Security, and International Affairs at the University of Central Florida.

Abigail Reynolds is a Researcher at the University of Central Florida and a current Boren Scholar in the study of Swahili.

Dr Mwita Chacha is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Birmingham.

Endnotes

[1] Ntomba, Reginald (2015) ‘Why are Military Coups Going out of Fashion in Africa?’ New African, 11 November, Available at: <https://newafricanmagazine.com/11522> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[2] Schiel, Rebecca; Faulkner, Chris; and Powell, Jonathan (2017) ‘Silent Guns: Examining the Two-year Absence of Coups in Africa’, Political Violence at a Glance, 18 September, Available at: <https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2017/09/18/silent-guns-examining-the-two-year-absence-of-coups-in-africa> [Accessed 10 November 2021].

[3] Camara, Kamissa (2017) ‘En Afrique de l’Ouest, Les Révisions Constitutionnelles Ont-elles Contribué à la Consolidation de la Paix et de la Démocratie, ou l’inverse?’ Africa Research Institute, 18 October, Available at: <https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/blog/en-afrique-de-louest-les-revisions-constitutionnelles-ont-elles-contribue-la-consolidation-de-la-paix-et-de-la-democratie-ou-linverse> [Accessed 10 November 2021].

[4] Souaré, Issaka (2014) ‘The African Union as a Norm Entrepreneur on Military Coups d’état in Africa (1952–2012): An Empirical Assessment’, Journal of Modern African Studies, 52(1), 69–94; Powell, Jonathan; Lasley, Trace; and Schiel, Rebecca (2016) ‘Combating Coups d’état in Africa, 1950–2014’, Studies in Comparative International Development, 51, 482–502.

[5] Campbell, John (2020) ‘The Changing Style of African Coups’, Council on Foreign Relations, Available at: <https://www.cfr.org/blog/changing-style-african-coups> [Accessed 5 November 2021].

[6] Unless otherwise noted, data on the number of coups are taken from Powell, Jonathan and Thyne, Clayton (2011) ‘“Global Instances of Coups” from 1950-2010’, Journal of Peace Research, 48(2), 249–259. The data have been updated to include the 25 October 2021 coup in Sudan.

[7] Ibid

[8] Faucon, Benoit; Said, Summer; and Parkinson, Joe (2021) ‘Military Coups in Africa at Highest Level Since End of Colonialism’, Wall Street Journal, 4 November, Available at: <https://www.wsj.com/articles/military-coups-in-africa-at-highest-level-since-end-of-colonialism-11635941829> [Accessed 5 November 2021]

[9] The Economist (2021) ‘As Sudan’s Government Wobbles, Coups are Making a Comeback’, 25 October, Available at: <https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/10/25/as-sudans-government-wobbles-coups-are-making-a-comeback> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[10] Meldrum, Andrew (1997) ‘Coups No Longer Acceptable: OAU’, Africa Renewal, July, Available at: <https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/july-1997/coups-no-longer-acceptable-oau> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[11] OAU (1999) ‘Declarations and Decisions Adopted by the Thirty-fifth Assembly of Heads of State and Government’, Ordinary Session of the OAU, Algiers, Algeria, 12-14 July, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/9544-1999_ahg_dec_132-142_xxxv_e.pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2021].

[12] OAU (2000) ‘Declaration on the Framework for an OAU Response to Unconstitutional Changes of Government’, Lomé, Togo, 10–12 July, Available at: <http://archives.au.int/handle/123456789/915> [Accessed 15 November 2021].

[13] Ibid.

[14] AU (2007) ‘African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance’, Eighth Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the AU, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 30 January, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36384-treaty-african-charter-on-democracy-and-governance.pdf> [Accessed 15 November 2021].

[15] Lebow, Richard N. and Gross-Stein, Janice (1990) ‘Deterrence: The Elusive Dependent Variable’, World Politics, 42(3), 336–369.

[16] Souaré, Issaka (2014) op. cit.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Powell, Jonathan et al. (2016) op. cit.

[19] AU (2008) ‘Communique of the 144th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 7 August, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/2008-144-comm-c1e.pdf> [Accessed 14 November 2021]; AU (2009) ‘Communique of the 168th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 5 February, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/communiquemeeting.pdf>[Accessed 14 November 2021].

[20] AU (2009) ‘Communique of the 196th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 29 June, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/pcscommuniquemauritaniafr.pdf> [Accessed 14 November 2021]; New York Times (2009) ‘Coup Leader Wins Election Amid Outcry in Mauritania’, 19 July, Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/20/world/africa/20mauritania.html> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

[21] AU (2013) ‘Communique of the 384th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 5 July, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-384-com-egypt-05-07-2013.pdf> [Accessed 14 November 2021]; AU (2014) ‘442nd Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 17 June, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-com-442-egypt-17-06-2014.pdf> [Accessed 14 November 2021].

[22] AU (2014) ‘Communique of the 465th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, 3 November, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-465-com-burkina-faso-03-11-2014.pdf> [Accessed 5 November 2021].

[23] Dersso, Solomon (2014) ‘Protests have Ended Blaise Compaoré’s Reign’, Institute for Security Studies, 11 November, Available at: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/the-au-on-burkina-fasos-arab-spring> [Accessed 5 November 2021]; Bonkoungou, Mathieu and Coulibaly, Nadoun (2014) ‘Burkina Faso Names Army Colonel Zida as Prime Minister’, Reuters, 19 November, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-burkina-politics/burkina-faso-names-army-colonel-zida-as-prime-minister-idINKCN0J31XZ20141119>

[24] Institute for Security Studies (2014) ‘Popular Ousting of Compaoré Not Considered Contrary to AU Norms’, PSC Report, 11 November, Available at: <https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/popular-ousting-of-Compaoré-not-considered-contrary-to-au-norms> [Accessed 10 November 2021].

[25] Roessler, Philip (2017) ‘How the African Union Got it Wrong on Zimbabwe’, Al-Jazeera, 5 December, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/12/5/how-the-african-union-got-it-wrong-on-zimbabwe> [Accessed 5 November 2021].

[26] Banjo, Adewale (2008) ‘The Politics of Succession Crises in West Africa: The Case of Togo’, International Journal on World Peace,25(2), 33–35.

[27] AU (2005) ‘Communique of the Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the Peace and Security Council’, Available at: <https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/communiqueeng-25th.pdf> [Accessed 5 November 2021].

[28] US Bureau for Public Affairs, Press Relations Office (2005) ‘Togo: Imposition of Sanctions by the Economic Community of West African States’, US Department of State, 19 February, Available at: <https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2005/42493.htm> [Accessed 20 October 2021].

[29] Handy, Paul-Simon and Djilo, Félicité (2021) ‘AU Balancing Act on Chad’s Coup Sets a Disturbing Precedent’, Institute for Security Studies, 2 June, Available at: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/au-balancing-act-on-chads-coup-sets-a-disturbing-precedent> [Accessed 5 November 2021].

[30] Nichols, Michelle (2021) ‘“An Epidemic of Coups”,UN Chief Laments,Urging Security Council to Act’, Reuters, 26 October, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/world/an-epidemic-coups-un-chief-laments-urging-security-council-act-2021-10-26> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[31] Ibid.

[32] Marinov, Nikolay and Goemans, Hein (2014) ‘Coups and Democracy’, British Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 799–825; Thyne, Clayton and Powell, Jonathan (2016) ‘Coup d’etat or Coup D’autocracy: How Coups Impact Democratization, 1950-2008’, Foreign Policy Analysis, 12(2), 192–213.

[33] Ikome, Francis Nguendi (2007) ‘Good Coups and Bad Coups: The Limits of the African Union’s Injunction on Unconstitutional Changes of Power in Africa’, Institute for Global Dialogue, Occasional Paper No. 55, February, Available at: <http://igd.org.za/jdownloads/Occasional%20Papers/igd_occasional_paper_55.pdf> [Accessed 2 November 2021]; Miller, Michael (2012) ‘Economic Development, Violent Leader Removal, and Democratization’, American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 1002–1020; Powell, Jonathan (2014) ‘An Assessment of the “Democratic” Coup Theory: Democratic Trajectories in Africa, 1952-2012’, African Security Review, 23(3), 213–224; Thyne, Clayton and Powell, Jonathan (2016) op. cit.; Marinov, Nikolay and Goemans, Hein (2014) op. cit.

[34] Death data are updated from Powell, Jonathan and Chacha, Mwita (2019) ‘Closing the Book on Africa’s First Generation Coups’, African Studies Quarterly 18 (2), 87-94. Available at: <http://asq.africa.ufl.edu/files/v18i2a6.pdf> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[35] President João Bernardo Vieira of Guinea-Bissau was murdered by a group within his armed forces in March 2009. Though killed at the hands of the military, Vieira’s death is not considered a coup according to various definitions and data projects since the perpetrators took no steps to assume power or determine succession. Earlier examples of excluded assassinations include the death of Laurent Désiré Kabila (Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2001) and Mohamed Boudiaf (Algeria, 1992). Failed coups that resulted in the killing of the chief executive, such as Murtala Mohammed (Nigeria, 1976), are also excluded.

[36] This statistic likely underreports deaths by excluding individuals who were effectively given death sentences via conditions of their imprisonment. Grégoire Kayibanda, for example, is believed to have been intentionally starved to death following his ousting from the Rwandan presidency in July 1973. As he is believed to have lived for three years, he is excluded as a case here.

[37] Thomas, Abdul Rashid (2021) ‘ECOWAS Heads of State Suspend Guinea and Hold Junta Responsible for Safety of Conde’, The Sierra Leone Telegraph, 10 September, Available at: <https://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/ecowas-heads-of-state-suspend-guinea-and-hold-junta-responsible-for-safety-of-conde> [Accessed 14 November 2021].