Introduction

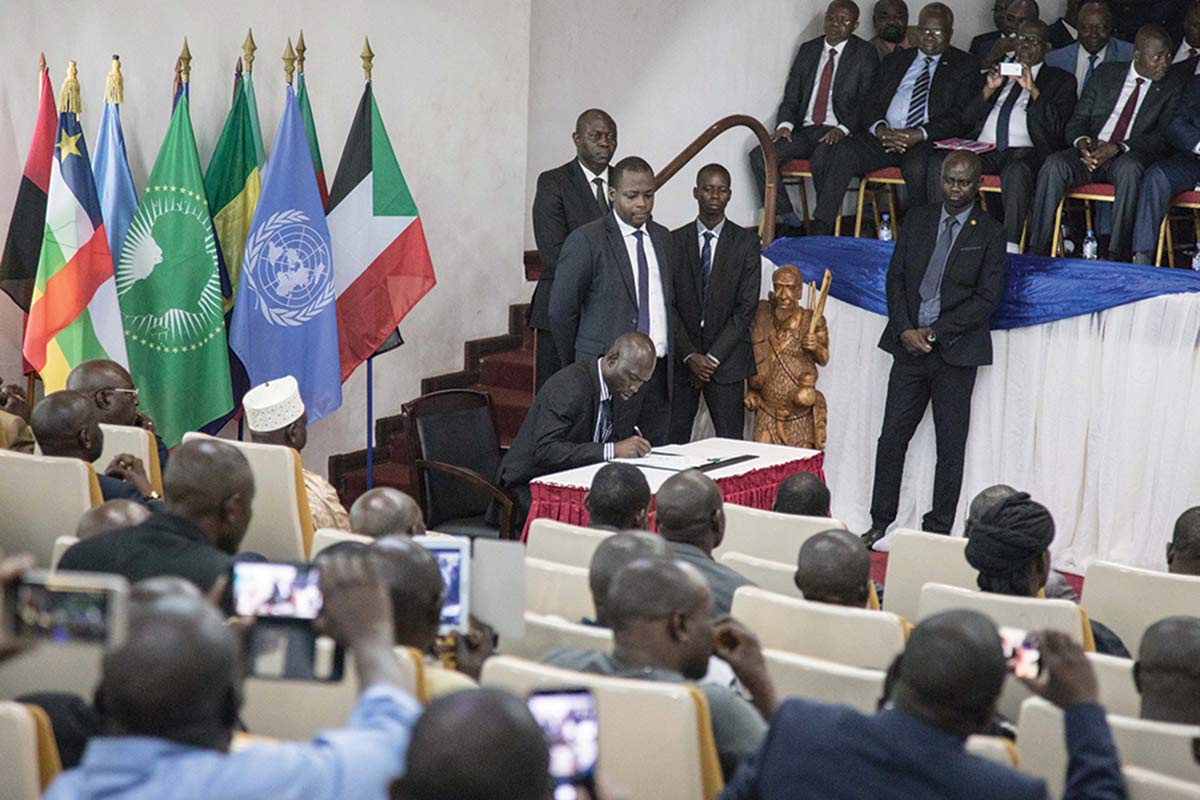

On 6 February 2019, a peace agreement was signed between the government of the Central African Republic (CAR) and 14 armed groups that control most of the country. After two weeks of talks in Sudan, the Khartoum Agreement was agreed upon to end years of civil war in the CAR. While the agreement is seen by some as a step towards lasting peace, others are sceptical about its viability.1 Such pessimistic reactions are understandable for several reasons. First, the Khartoum Agreement is the eighth of such agreements to attempt to bring peace to the CAR since the country descended into conflict in 2013. Second, less than a month after the new peace agreement was signed, one of the 14 armed groups that signed the agreement abandoned the deal, while another armed group quit a new government designed to be the keystone to the agreement.2 The failure of such peace agreements to stabilise the CAR suggests a need to examine the role of leadership in processes of building peace.

Since independence in 1960, the CAR has suffered five successful coups d’état. The 2013 coup, orchestrated by the Séléka – Séléka means “coalition” in the Sango language – occurred against the backdrop of a phantom state and a collapsed economy.3 The Séléka rebels opposed the regime of President François Bozizé. After Bozizé fled from the CAR to neighbouring Cameroon, Michel Djotodia, head of the Séléka, declared himself president of the country on 25 March 2013. Due to the perception that the Séléka was a foreign Muslim force pillaging and perpetrating deadly violence in a country with a Christian majority, the CAR sank into an unprecedented ethno-religious conflict, predominantly between the Séléka and the mostly Christian Anti-Balaka groups. As a result, the international community and regional powers increased pressure on Djotodia to step down; he yielded on 10 January 2014. Catherine Samba-Panza took the lead as interim president that same month, paving the way for the election of Faustin-Archange Touadéra as president of the CAR in March 2016.4 However, instability and violence continued, in spite of these political transitions and the measures put in place to stop the fighting, reconcile warring parties and stabilise the CAR.

This article argues for a process-based leadership perspective for achieving sustainable peace in the CAR. A process-based approach to leadership, rather than one that narrowly focuses only on particular personalities or individuals in formal positions of authority, offers a potential for peaceful solutions that are the product of interaction between those administering peace and the whole of the affected society receiving peace. Process-based leadership is conceptualised as process – it opens up the possibility of finding lasting solutions to conflict, from within wider society.5 This article looks at the historical and contemporary roots of conflict in the CAR. The dilemma of peacebuilding in the CAR is then discussed, followed by leadership as a process in peacebuilding.

The Roots of Conflict in the CAR

The roots of conflict that characterise the political system of the CAR have been traced back to the colonial period. During this time, the CAR, unlike other French colonies in Africa, was largely neglected by the colonial power.6 Rather than develop an administration, French colonial officials leased the territory to private companies to run for their own profit (or loss).7 This privatisation of public space has been a recurrent practice throughout the country’s history.8 Opposition to colonial authorities and the recruitment and mistreatment of local populations by concessionary companies further contributed to the culture of resistance and self-defence among local communities.9 However, the economic exploitation of the colony did not result in social and economic development.

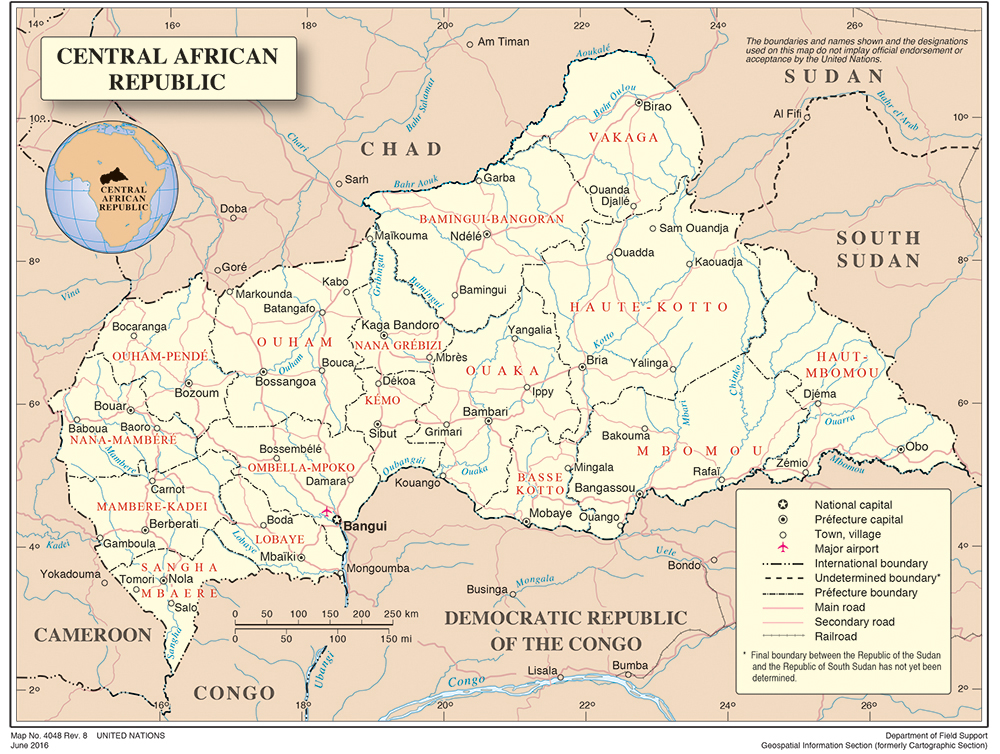

By independence in 1960, infrastructure in the CAR was virtually non-existent.10 More so, the post-independence period was characterised by a disequilibrium between the rural areas and the centre of power, Bangui, and inequalities between different groups within the population – all leading to the underdevelopment of the country. Regions outside of Bangui have consequently become marginalised, to the detriment of populations and ethnic groups living in those areas. This has resulted in a weak state that has little capacity or political will to govern beyond the capital.11 The government’s failure to provide services to outlying regions in the north and east is a major grievance and a key driver of conflict. This, in turn, perpetuates the cycle of conflict, poverty and grievances, and the further subcontracting of governance to international organisations. This fractured social landscape has created deep distrust between communities, and between the general population and the central government.12

Consequently, it has triggered politics of religion and identity by adding to the narrative that the government does not care about its Muslim citizens – many of whom already share greater social connections with communities in Chad and Sudan. In turn, this helps ferment opposition against Muslims by Christians, resulting in the narrative that Muslim Séléka forces, supported by foreign powers, are trying to “Islamise” central African society.13 The institutional crisis has also been both the cause and consequence of the near collapse of the country’s economy. The introduction of economic liberalisation in the late 1980s reduced the state’s capacity and position to distribute resources, and structural adjustment programmes seem to have further contributed to the downfall of the CAR. The formal economy was drastically reduced as foreign companies gradually left the country, and unemployment became the common fate of a large part of the population. Furthermore, for years the CAR’s natural wealth has flowed out of the country rather than being used for local development. This has created a system whereby CAR politicians are often more concerned with the personal relationships they hold with these outside sources of power than with fulfilling their social contract with CAR citizens.14 The military’s interference in political and civil affairs has further resulted in a cyclical pattern of political instability, economic stagnation and social dissatisfaction.

It is clear that the CAR is faced with the need to address the structural problems inherited from the colonial power, as well as challenges arising from its leadership. To respond to and address the structural problems, leadership should take into consideration a broad understanding of the comprehensive challenges facing the citizens of the CAR, build the eroded social cohesion, and design measures to address such challenges, among other things.

The Challenges of Peacebuilding in the CAR

A careful examination of the security situation in the CAR shows that the key challenges confronting national, regional and international peacebuilders in the country are conflict relapse and conflict resurgence. Conflict relapse refers to decline into armed conflict in a number of situations that have experienced concerted peacemaking and peacebuilding interventions, while conflict resurgence occurs when armed conflict increases after a period of concerted peacebuilding interventions.15 For example, the Bangui Forum was organised from 4 to 11 May 2015 to collect people’s grievances and concerns.16 Although the forum was seen as a sign of hope for the country, there was conflict relapse. Also, the failure of successive peace agreements between the warring parties revealed similar patterns of relapse. This is consistent with research, which indicates that a significant percentage of armed conflicts that conclude through negotiated settlement have a chance of relapse within 10 years.17 Similarly, in some cases in the CAR, rather than end instability and armed conflict, peace agreements can add layers of further violence and division. The impact of both conflict relapse and conflict resurgence in the CAR is devastating and deadly.

Against this backdrop, the need for prevention of armed conflict in the first instance and prevention of its relapse or resurgence where conflict was not prevented seems obvious and necessary.18 More so, African countries have realised the importance of prevention rather than reaction, because the costs of reaction are high. Despite this realisation, armed conflict in the CAR still represents high costs of reaction, as regional and international bodies such as the African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN) respectively have expended huge investments to respond to the armed conflict in the country. Thus, addressing the challenges of peacebuilding in the CAR requires a broad understanding of factors responsible for conflict relapse and conflict resurgence, followed by prevention commitment.

Process-based Leadership in Peacebuilding

Many studies of leadership reveal multiple interpretations of what constitutes process-based leadership.19 Typically, much emphasis is placed on individual leaders and their actions or inactions – which, in many cases, serve to undercut rather than bolster the potential for peace and prosperity that exists in society. Some perspectives view leadership as a psychological endowment, or as result oriented.20 Others consider leadership as the ability of a country or coalition of countries to initiate and guide the actions of a wider group of states to sustainably satisfy common good and need.21 But none of these perspectives have consistently explained or delivered sustainable peace in conflicts in Africa, and the CAR in particular. How then must leadership be understood and applied if it is to have value with peacebuilding challenges?

A process-based approach to leadership offers perhaps the most robust and all-encompassing framework of analysis for the pursuit of sustainable peace. Central to a process-based approach to leadership in the search for sustainable peace is the societal exchange of influence in seeking solutions or responses to the situation confronting that society. This exchange of influence involves a process of interaction in which the whole society is involved in seeking solutions to their mutual situation.22 In the CAR, this important leadership element seems to have eluded peacebuilding interventions, as wider society has been excluded from peace processes. In addition, the wider society in the CAR are considered victims of conflict and/or recipients of humanitarian aid, while the process of peacemaking is an activity that concerns state actors, armed group leaders and international actors.23 As a result, the work achieved by such top-down approaches is undermined by communities at the local level (which continue to perpetuate the violence and conflict), where the root causes of conflict are often situated. Thus, leadership as a process in peacebuilding should provide for a societal exchange of influence for addressing the underlying issues of conflict.

Leaders who exert influence in peacebuilding contexts may not always hold formal positions in government or society, and therefore do not rely on position power. Nonetheless, these leaders have a sense of shared feelings or intentions among people experiencing a particular situation, and offer the most viable ideas and solutions to the mutually felt needs of the affected society in that situation.24 For example, religious leaders in the CAR have successfully harnessed their symbolic influence to call for restraint, and in the provinces, priests have successfully mediated local conflicts.25 In line with this summation, it is important for external actors seeking to intervene in war-affected societies to understand the context and recognise those leaders with whom a sufficiently broad cross-section of that society have mutually held needs and goals.26 This offers a more viable path to peace rather than an approach that simply seeks to identify individuals outside of that context (or sometimes within), who may have attractive personal qualities but are irrelevant to the situation at hand.27 Adopting this perspective offers a better lens for understanding conflict and peacebuilding dynamics.

The CAR is an example of the lack of process-based leadership in peacebuilding, which has engendered political instability, violence and disillusionment. The common leadership efforts in the country centre on interactions between national elites and international interlocutors. The outcome of this is often the control of the state and its resources by the elites. The interference of the military in the state with external backing has further produced a leadership approach that is based on amassing power and authority by the elites, rather than exchanging influence with CAR citizens. Thus, achieving sustainable peace in the CAR requires an “exchange of influence” between the leaders administering peace and the wider society receiving peace, with a focus not only on the emergence of leaders through elections but also on reconciliation, relationship-building and addressing the structural causes of the conflict.

Exchange of Influence: The Missing Link

Leadership emergence in the CAR has been characterised by the influence of external actors. France is highly influential in the internal processes of the CAR. For example, a French-sponsored coup led by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, a colonel in the CAR military, overthrew the regime of David Dacko in 1960. Whereas Dacko was removed due to his close ties to China, Bokassa was chosen because of his devotion to France and his anti-communist stance. Eventually, France had problems with Bokassa, too, and stopped supporting him.28 In addition, there is the Chadian interference in the CAR’s domestic affairs. Chad’s president, Idriss Déby, has been at least as influential in CAR politics as has the former colonial power. In fact, Chad has become known as the “king maker” in the CAR over the last few decades. In 2003, Bozizé benefited from Chadian support to topple the Ange-Félix Patassé regime. Likewise, in 2013, Djotodia received support from Chad to ascend to power.29 The lack of substantive exchange of influence within the CAR population served as one basis for the rejection of Djotodia’s government and subsequent conflict, as future incentives for conflict were not reduced. The exchange of influence in peacebuilding entails the involvement of the CAR population in the emergence of leaders with ideas to deal with the issues at hand, and whose influence on the population is accepted. The population receiving the leadership influence often responds by asserting influence in return – that is, by making demands on the leaders. Most simply, the leaders with ideas assert influence by sharing them with the wider society – which, in turn, accepts this assertion of influence if and when they are seen to offer a relevant solution.30 However, wider society in the CAR was excluded from the exchange of influence, and therefore the scope of relationships and interactions were reduced.

The decision to form a transitional government in 2015, which resulted in Samba-Panza becoming president, was tasked with the main aim of guiding the CAR to elections. This decision was reached during an Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) summit in Chad’s capital, Ndjamena.31 In addition, the decision stopped Samba-Panza, Djotodia and Bozizé from contesting the elections. However, the process did not include discussions on the structural causes of successive coups. The process only involved discussions on the immediate planning of elections as a resolution to the trigger causes of the conflict. Furthermore, the process of selecting Samba-Panza as the president was concluded in Chad, under the influence of Déby, together with France and ECCAS.32 Such leadership emergence occurs when forces outside the group assign leadership to an individual and assert their influence in the acceptance of the individual as a leader.33 This is different from process-based leadership, which calls for representation of wider society at the negotiation table and involvement in choosing the leaders, even in transitional periods.

The 2016 elections were supposed to mark the end of the transitional period and produce a new government. However, the timing – which was dictated by the international community – did not only underestimate the complexity of the conflict, it also impaired the dynamic nature of the leadership process by undermining the process of building societal relations that would have anchored an enduring process of peacebuilding. More so, the elites’ preoccupation with elections reflects the fact that external political agendas, not always aligned with local needs, have heavily influenced the conflict resolution process.34 This, however, does not downplay elections. It only means that the participation of wider society should determine the importance and sustainability of a democratic process.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This article argues for a peace process anchored in process-based leadership to achieve sustainable peace in the CAR. Several peacebuilding measures and processes, including the latest peace agreement, have been put in place to address the unresolved instability and armed violence in the CAR. However, the missing link seems to be the exchange of influence, as a process-based leadership approach for sustainable peace did not occur in the CAR. Despite political transitions and successive peace agreements, the absence of sustainable peace continues to point to the fact that the exchange of influence between elites and citizens of the CAR is minimal – and, in many cases, such exchanges never took place. There is a need to build sustainable peace in the CAR through interactions and the exchange of influence between those who are offering peace and the affected society receiving peace. This would require committed efforts towards relationship building and addressing the structural causes of the conflict by all relevant stakeholders.

Endnotes

- Agency Staff (2019) Central Africa Republic Peace Deal under Strain. Business Day, 4 March, 16:44.

- Ibid.

- Dukhan, Nathalia (2016) ‘The Central African Republic Crisis’, Available at: <http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/car_gsdrc2013.pdf> Accessed 19 April 2019.

- Douglas-Bowers, Devon (2015) ‘Colonialism, Coups, and Conflict: The Violence in the Central African Republic’, Available at: <http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com> Accessed 19 April 2019.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) Towards Re-conceptualising Leadership for Sustainable Peace. Leadership and Developing Societies, 2 (1), pp. 1–30.

- Akasaki, Genta, Ballestraz, Emilie and Sow, Matel (2015) What Went Wrong in Central African Republic? International Engagement and Failure to think Conflict Prevention. Geneva Peacebuilding Platform, Paper No. 12.

- Knoope, Peter and Buchanan-Clarke, Stephen (2018) Central African Republic: A Conflict Misunderstood. Occasional Paper 2, The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

- Carayannis, Tatiana and Fowlis, Mignonne (2017) Lessons from African Union–United Nations Cooperation in Peace Operations in the Central African Republic. African Security Review, 26 (2), pp. 220–236.

- Knoope, Peter and Buchanan-Clarke, Stephen (2018) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Akasaki, Genta, Ballestraz, Emilie and Sow, Matel (2015) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) op. cit., p. 3.

- Dukhan, Nathalia (2016) op. cit., p. 27.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) op. cit., p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Elcock, Howard (2001) Political Leadership. United States: University of Michigan; Kiwer, Kiven James and Ngah, Gabriel (2018) Joint-Leadership and Regional Peacebuilding in Africa. Journal of African Union Studies, 7 (3), pp. 9–24; and Grint, Keith (2010) Leadership: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nyokabi, Kamau (2016) Leadership and Peacebuilding in Guinea-Bissau: Examining the Coup of 14 September 2003. Leadership and Developing Societies, 2 (1), pp. 31–56.

- Kiwer, Kiven James and Ngah, Gabriel (2018) op. cit., p. 2.

- Nyokabi, Kamau (2016) op. cit., p. 43.

- Douglas-Bowers, Devon (2015) op. cit.

- Nyokabi, Kamau (2016) op. cit., p. 43.

- Conciliation Resources (2015) ‘Analysis of Conflict and Peacebuilding in the Central Africa Republic’, Available at: <https://www.c-r.org/resources/analysis-conflict-and-peacebuilding-central-african-republic> Accessed April 2019.

- Nyokabi, Kamau (2016) op. cit., p. 43.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Douglas-Bowers, Devon (2015) op. cit.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) op. cit.

- Carayannis, Tatiana and Fowlis, Mignonne (2017) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Olonisakin, Funmi (2016) op. cit.

- Dukhan, Nathalia (2016) op. cit., p. 27.