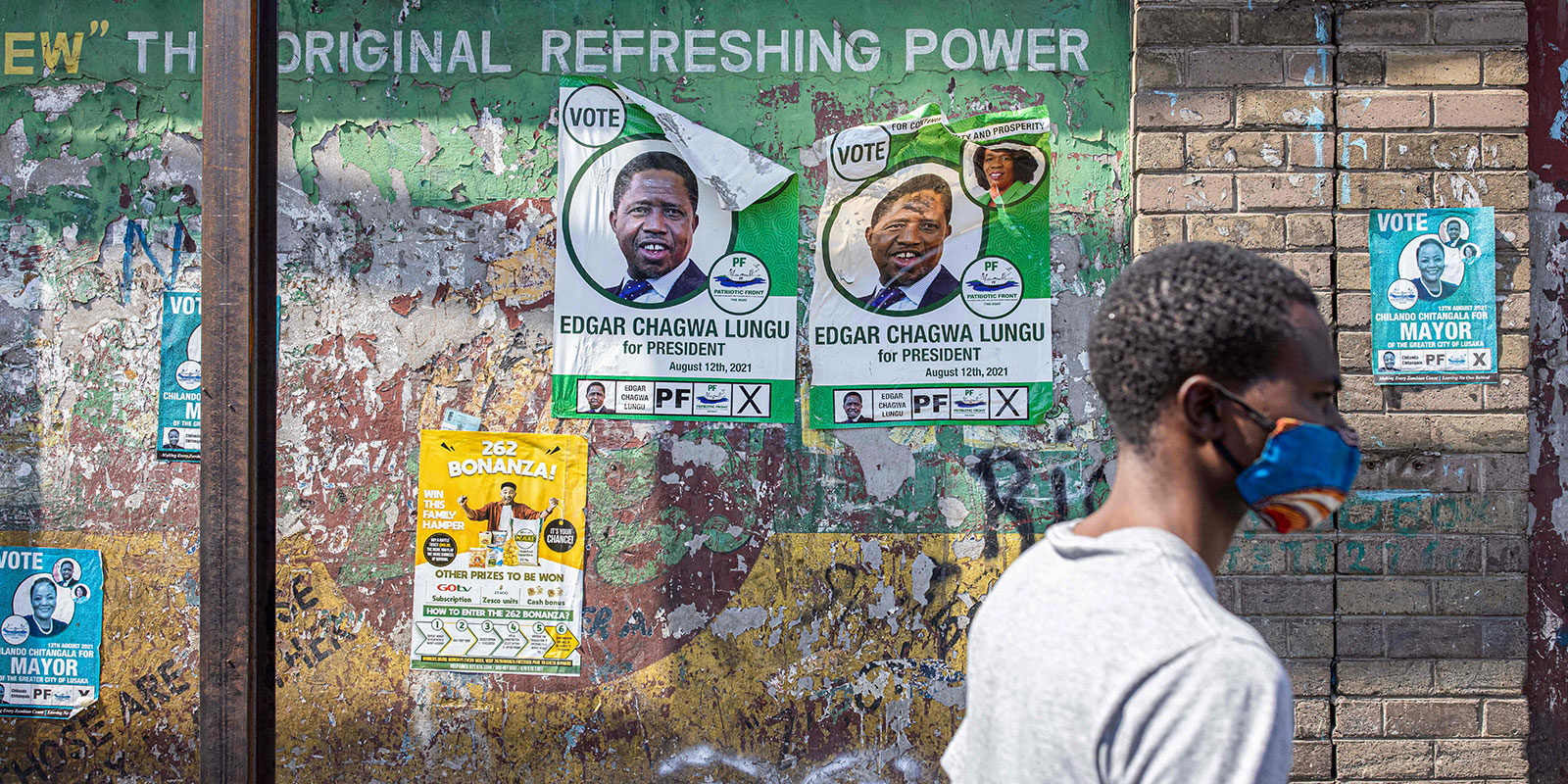

On 24 August 2021, Zambia’s seventh republican president, Mr. Hakainde Hichilema fondly known as HH of the United Party for National Development (UPND) was sworn in. While his ascent to power was a resounding triumph in the 2021 presidential elections, the canvassing was coarse. In addition to circumscribed political space to campaign, he was also a target of hate speech and tribal rhetoric from some political opponents. Although uttered within the ambit of electioneering, there are inescapable after effects especially in sustaining social cohesion.

The common good pursuit in the context of Zambia invokes national efforts to achieve a just society that inspires national unity through constructive social and political interactions. #Zambiadecides2021 #C19ConflictMonitor

Tweet

Social cohesion entails closeness, synchronisation and strength of relationships between members of a unit1Taylor, Jacob and Davis Arran 2018. Social Cohesion. In: Callan, Hilary ed. The International encyclopedia of anthropology. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, p.1 and the polity is no exception. In addition to some benefits accruing to the political entity or the broader society, cohesion enhances members’ willingness to individually or collectively contribute to a common vision of sustainable peace and unity. However, the modus operandi of some senior political leaders aligned with the ruling Patriotic Front (PF), party during Zambia’s 2021 election campaigns was an affront to social cohesion. At least three dimensions illuminate this slur.

First, unwarranted and widespread hate language against the Tonga ethnic group and HH as a Tonga, unquestionably induced ‘social cleavages and polarisation’. In other words, the polarity was not only political but social, as Hichilema and his party received massive (‘protest’) votes from across the country despite PF’s aligned leaders’ unrelenting hate speech. The perpetuation of tribal biases further overshadowed real social and economic issues that ought to have taken centre stage during campaigns. The adverse effect of social cleavages and polarisation was apparent in attacks albeit isolated on some individuals and properties associated with the PF following the announcement of election results. The spread of tribal prejudices against the UPND (as a Tonga party) and HH was an implicit factor and impetus that may have steered voters, young people especially to act in solidarity with the UPND. Their voting en masse on 12 August 2021 also revealed growing frustration with pitiable socioeconomic conditions under PF rule.

Second, tribal utterances during campaigns may have also weighed in on fracturing community members’ ‘sense of belonging’. People’s confidence in social and political institutions, a crucial dimension of connectedness within the social cohesion jurisdiction easily withers with hate speech. This was not only divisive but an assault on diversity, inclusion, tolerance and national unity. A society will cohere when individuals have a sense of belonging and see unrestrained opportunities to participate, socially and politically, with respect and tolerance of diversity. However, hate language during the 2021 elections campaigns, not only kindled the ‘Us versus Them’ dichotomy but recharged tribal lines that Zambia’s first president the late Dr. Kenneth Kaunda worked hard to erase. Sadly, the failure by the leadership of PF to categorically censure those at the helm of hate speech and tribal sentiments may have validated perceptions that the party ordained the vice. While this, to some degree may inure the party’s stalwarts to hate, it is deleterious for the Zambian society and undermines social cohesion. Along with predisposing communities to violent confrontations, hate language corrodes shared national values and principles such as morality, patriotism and national unity.

In keeping with the commitment from Mr. Hichilema, his administration as ‘servants of the Zambian people’, should preside over the country’s affairs without partiality of any group over another #Zambiadecides2021 #C19ConflictMonitor

Tweet

Third, campaigns during the 2021 elections brought to the fore, ‘triviality of the common good’ especially by those that rode on hate speech and tribal rhetoric against HH and the UPND. Within social cohesion parlance, committing to the common good, suggests participating in upholding Zambia’s philosophy of One Zambia One Nation. Put differently, the common good pursuit in the context of Zambia invokes national efforts to achieve a just society that inspires national unity through constructive social and political interactions. Woefully, the country’s maxim was relentlessly mutilated during campaigns through hate language.

Nonetheless, President Hichilema and the UPND’s victory has transcended tribal and polarisation lines that some contenders wished were kept afloat. Moving forward particularly for the new ruling party, the need to embody the country’s motto is great. Further, a resolve to build confidence in institutions and political leadership is not only a political necessity but a social imperative. Consistent with the social cohesion domain, efforts to reverse the erosion of the sense of community evident in inequalities, social cleavages, polarisation and strained relations remains essential. As a new beginning, sanitising the Zambian polity is undoubtedly necessary, that is ensuring some of the country’s values are invigorated – ‘human dignity, equity, social justice, equality, tolerance, non-discrimination, good governance and integrity’.

In sum, while these values reinforce social cohesion tenets, the obligation to thwart ugly acts of tribal rhetoric during canvassing before slipping into polarisation and hostility rests with the new regime. And in keeping with the commitment from Mr. Hichilema, his administration as ‘servants of the Zambian people’, should preside over the country’s affairs without partiality of any group over another.

Kabale Ignatius Mukunto is a Lecturer at the Dag Hammarskjöld Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, Copperbelt University in Kitwe, Zambia.