Amid the worst drought in over 40 years, Ethiopia’s high exposure to climate change and its devastating impacts is growing increasingly evident by the day. While exact estimates are uncertain, it is predicted that the temperature will increase by between 0.5∞C and 2∞C by 2050 and rainfall is expected to become more erratic as the rainy and dry season become increasingly unpredictable.

With high levels of human insecurity and limited state capacity, climate change poses significant security risks in Ethiopia.

Tweet

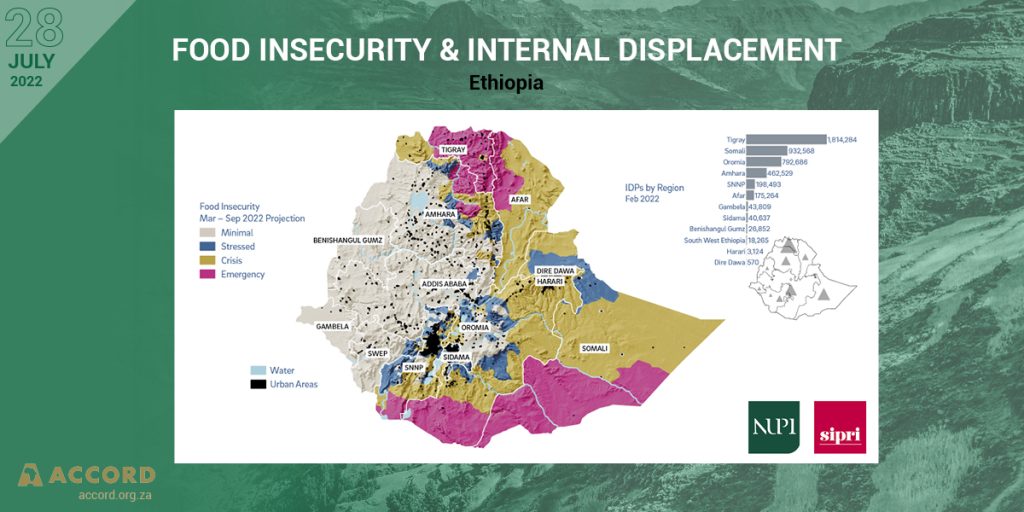

Despite having one of the world’s fastest-growing economies in the last 15 years, Ethiopia continues to grapple with rapid urbanisation, a young population and high levels of poverty and food insecurity. This is compounded by Ethiopia’s complex conflict landscape, characterised by several protracted communal conflicts as well as the armed conflict in the Tigray region. Heightened conflict levels augment people’s vulnerability to climate change by increasing displacement and food insecurity and reduce possibilities for Ethiopians to cope with and adapt to increasing temperatures, drought, and erratic rainfall. Continued conflict and armed violence also reduce federal and state capacity to effectively implement Ethiopia’s comprehensive climate change adaptation and mitigation policies, including its ambitious Climate-Resilient Green Economy strategy.

With high levels of human insecurity and limited state capacity, climate change poses significant security risks in Ethiopia. Efforts to tackle the humanitarian crisis in Ethiopia and improve the stability of the country must take into consideration the way in which the impacts of climate change interact with political, social and environmental stresses and compound existing vulnerabilities and tensions.

Livelihood deterioration, changed migratory patterns and violent conflict

In Ethiopia, climate-related security risks are especially relevant in relation to the use of land by farmers and herders. Through increased frequency and intensity of drought and flooding, climate change is set to worsen land degradation and reduce ecosystem services in Ethiopia, ultimately reducing agricultural outputs and putting livelihoods dependent on agriculture at risk. Some 85 per cent of the population is dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods, and the agricultural sector is characterised by small-scale farming and rain fed crops. In addition, as pastoralism makes up 12-16 per cent of Ethiopia’s GDP, recurring droughts threaten the livelihood of more than 12 million Ethiopians dependent on livestock.

Women and female-led households, particularly in rural parts of Ethiopia, face financial, technical and knowledge barriers to adapting to climate change, reducing their ability to diversify their livelihoods, making women and girls especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. For instance, reduced water availability means that more time is spent collecting water due to either a complete lack of water or long access queues. As this is often the responsibility of women and girls, one consequence is that girls are kept home from school in order to assist in water collection.

As climate change makes people’s livelihoods unsafe and more unpredictable, resource scarcities can exacerbate pre-existing competition over land and water, increasing the risk of contributing to or exacerbating conflict. Heightened levels of communal conflict over access to land and water following shifting politics at the federal level after the 2018 election, have led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, especially in Oromia, the Southern Nations and the outskirts of Addis Ababa.

Through changing seasonal patterns and accelerating biodiversity loss and environmental degradation, climate change contributes to changing mobility patterns for many of Ethiopia’s pastoralist communities. Seasonal migration is a fundamental part of pastoralist life, constituting a key coping mechanism for seasonal fluctuations. As climate change alters seasonal fluctuations and predictability, pastoralists have changed their seasonal migration patterns, both when it comes to the timing and location of their movement. This has contributed to heightened tension over land access and resources, especially between farmers and herders. For example, drought has been found to increase the competition between Karrayyu and Afar herders as it reduced access to rangeland. Increased travel distances also mean more livestock deaths and sometimes increased ethnic violence.

State introduction of formalised property rights across pastoral land and policies of large-scale land leasing have added to conflicts over land by exacerbating issues of exclusion and access. In several instances, land utilised by pastoral communities in ways not recognised by the state has been subject to large-scale land leasing by foreign and domestic investors. The policy of enclosing areas from pastoralists has limited the pastoralists’ ability to adapt to climate change and therefore limit their searches for alternative migration routes.

With high levels of human insecurity and limited state capacity, climate change poses significant security risks in Ethiopia.

Tweet

Recommendations

The African Union (AU), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), United Nations system and other international partners should support government-led efforts to coordinate responses to the impact of climate change, including efforts to implement the Climate-Resilient Green Economy Strategy. Providing adequate climate finance to Ethiopia is essential as the Ethiopian population is substantively impacted by climate change, but has contributed little to it. Furthering climate justice requires the transfer of financial resources, technology and knowledge from high-emission global north states to historically low-emissions global south states like Ethiopia.

In order to minimise climate-related security risks, the Ethiopian government should ensure that it fulfils its obligations to provide access to information regarding the environment and access to participation in environmental decision-making to farmers and pastoralists. This is a key step in ensuring that its climate change and adaptation policies consider the needs of the people most dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods. As pastoralist lifestyles are highly adaptable to changes in climatic patterns and inhibit historical and cultural knowledge regarding the environment, pastoral knowledge should be drawn on in state-led climate adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Finally, the Ethiopian government should do its utmost to find a peaceful settlement to the conflict in Tigray, and support local conflict resolution mechanisms in communal conflicts. Armed conflicts have devastating impacts on human security and people’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change whilst also drastically reducing state capacity to tackle its effects. As such, there is a significant risk that the combined impacts of climate change and conflict will reinforce a ‘vicious cycle of instability and underdevelopment’.

Asha Ali and Anne Funnemark are Junior Research Fellows and Dr. Elisabeth L. Rosvold is a Senior Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). This article is a summary of the Climate Change, Peace and Security Fact Sheet on Ethiopiapublished by NUPI and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).