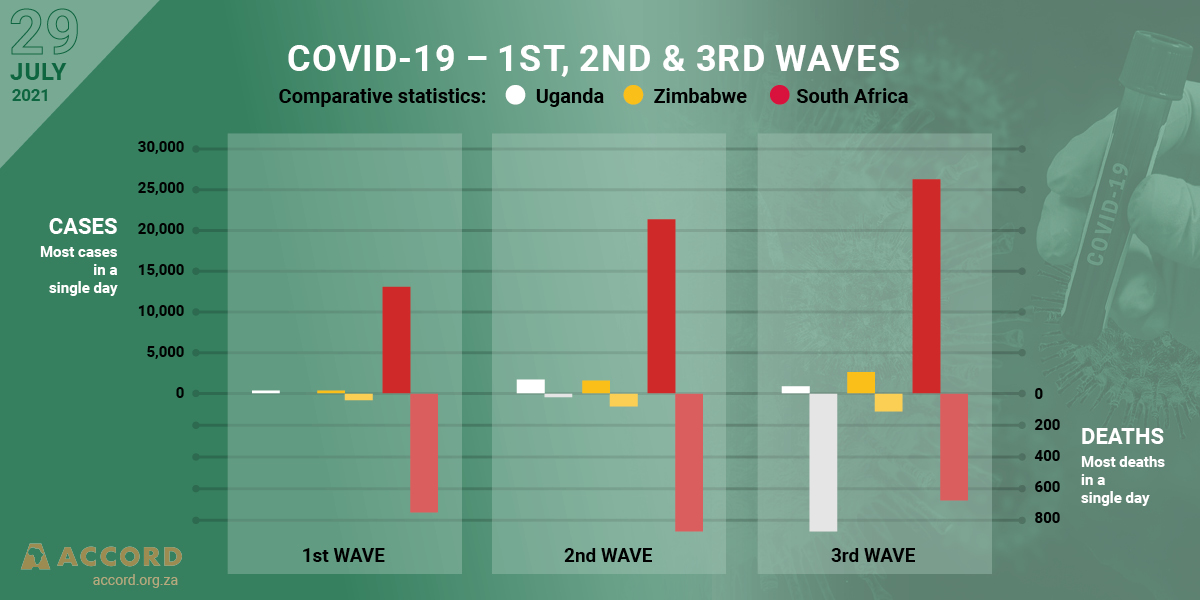

The more contagious Delta variant has meant that greater strain will be placed on African states’ healthcare systems as the latest variant becomes more dominant in Africa. In South Africa, where 30% of all COVID-19 cases in Africa have been detected, the province of Gauteng has been the hardest hit by the third wave, with many hospitals complaining of shortages of ICU beds and oxygen as they crippled under the strain of the third wave. Gauteng is proving to be a microcosm of many African countries, as oxygen and ICU bed shortages are being reported in six African countries. Due to this third wave many countries have once again entered into lockdowns in an attempt to slow down COVID-19 transmission. However, lockdowns remain a controversial measure and regulations remain disputed for a number of different reasons. This piece provides snapshots of responses from three African states namely; Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa where lockdowns have been particularly restrictive and have had a significant impact on state-society relations.

If populations do not consider the lockdown as legitimate or perceive it to be unfairly implemented, then people are less likely to obey the regulations that are ultimately put in place to protect them from the virus. @KEEN110997 @katharine_bebs

Tweet

Zimbabwe

With a total of 91,120 cases, Zimbabwe joins several other African countries in the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas previous waves mostly affected the urban areas, the third wave in Zimbabwe has seen a distinct rise in cases in the rural areas. Identified as hotspot areas, Mashonaland West (the area with the highest number of infections), Masvingo and Bulawayo provinces have all been placed under particularly strict lockdowns. This forms part of a new phase of government responses, some of which have exacerbated socio-economic problems or have created sources of tension between the state and local communities. The whole country is now operating under Level Four of a national lockdown with measures that include shorter working hours, an extended curfew, bans on intercity passenger travel, social and religious gatherings (with the exception of funerals with a limit of 30 people). In addition, there are shorter working hours and the early closure of all businesses from 6pm to 3pm which undoubtedly impacts on the livelihoods of many.

According to a post-cabinet briefing on 22 June 2021, the Zimbabwean Republic Police and Vehicle Inspection Department (V.I.D) were mandated to “increase surveillance to enforce compliance with COVID-19 regulations for ZUPCO intercity and intra-urban services”, referring to buses which travel between cities. The government has also called for a “joint security blitz” to enforce COVID-19 measures. While it is not entirely clear what such a blitz entails, such securitised responses from the government does not bode well for a country with a history of heavy-handed policing and one facing accusations of using COVID-19 restrictions to curtail freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of expression.

Like all governments attempting to navigate the challenges of the pandemic, Zimbabwe will have to strike a careful balance between restricting the spread of the virus and that of human rights and the economy.

Uganda

Uganda is one of the African countries currently experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases as a result of the Delta variant, with a 30% rise in cases in the space of one week. There are reports in Uganda that there is a shortage of oxygen and hospital beds in addition to a shortage of personal protection equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers. The Secretary-General of the Uganda Medical Association, Mukuzi Muhereza, painted a dire picture of people being turned away at hospitals due to a lack of space and capacity at the hospitals.

The government response to the surge in cases has been to place Uganda in a partial lockdown which includes restrictions on movement and the closure of schools, markets and places of worship across the country. It is also compulsory to wear facemasks in public and people who are found to be flouting the regulations face a two-month jail sentence. However, while lockdowns assist in stopping the spread of COVID-19, lockdowns can be implemented in a manner that may ultimately be more detrimental to the people.

During the past week the government banned the distribution of food to vulnerable people, citing that the distribution will likely lead to the spread of the virus. While the gatherings are likely to increase the risk of exposure to the virus, the question must be asked whether preventing the spread of COVID-19 should take precedence over the delivery of food to vulnerable people. However, in this instance the distribution of food parcels has been politicised by the government and the main opposition party in Uganda, with the government accusing the opposition of using food parcels as a tool to gain supporters. This suggests that worse the economic situations gets as a result of COVID-19, so more people might find themselves vulnerable of manipulation of political parties vying for power.

South Africa

South Africa currently also finds itself in the grip of a severe “third wave” of COVID-19 amid a stunted vaccine rollout, which has seen only 3.1% of the population vaccinated. Infection rates in the country hit a peak of 26,500 cases a day in early July but have since declined. The constant debilitating waves of coronavirus have battered South Africa’s already fragile economy and driven the Government to implement multiple lockdowns. Furthermore, recent violent unrest in the country which has been characterised by large scale looting and destruction of property may serve to exacerbate an already dire COVID-19 situation as the events may serve as a worthy vector for the virus to proliferate through already vulnerable communities. Moreover, about 120 private pharmacies were destroyed which led to the loss of about 47 500 vaccine doses. With South Africa set to hold local government elections on 27 October 2021, and in the midst of a third wave of coronavirus infections with a fourth wave anticipated to arrive in October, a formal inquiry was set up to determine whether the elections could be held freely and fairly during a time of COVID-19 resurgence. The inquiry was chaired by the esteemed Former Deputy Chief Justice, Dikgang Moseneke. Over 3000 inputs were considered with many stakeholders largely divided on the issue.

South Africa’s two major opposition parties, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the Democratic Alliance (DA) both had polarising opinions on the issue. EFF leader, Julius Malema, was not convinced by the government’s decision to schedule elections in October, holding major reservations over how free and fair elections could be held with lockdown regulations placing restrictions on campaigning. The DA on the other hand raised the notion that this could serve as an opportunity for the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) to redesign and refresh the way in which South Africa conducts elections, stressing that this could be done in a way which ensures South Africans their inalienable right to franchise.

On 20 July 2021, the inquiry recommended delaying elections as it was “not reasonably possible or likely” that the municipal vote would be free and fair, however, these recommendations are not binding on the IEC. A lot of uncertainty remains over what this decision means for the country, as analysts have suggested the constitution may have to be amended to accommodate delayed elections, since it requires that local government elections be held within 90 days of the expiry of the five-year term of a municipal council. What is clear, however, is that COVID-19 and its accompanying effects has thrown South Africa’s young democracy into uncharted territory.

While there are no easy answers, lockdowns need to be implemented in a manner in which they are seen to be to the benefit of the people and not in a manner that appears to be unnecessarily harsh as the government will then lose the co-operation of the population. If populations do not consider the lockdown as legitimate or perceive it to be unfairly implemented, then people are less likely to obey the regulations that are ultimately put in place to protect them from the virus. This may result in the lockdowns being ineffective in preventing the spread of the virus, while also being detrimental to the economy and activities such as education as restrictions are imposed on their operations.

Katharine Bebington, Keenan Govender and Andrea Prah are all based in the Research Unit at ACCORD.