Southern Africa is one of the regions in the world most affected by climate variability and change, adversely impacting people’s livelihoods and overall well-being through rising temperatures, decreasing precipitation and extreme weather events such as droughts, flooding and cyclones. From October 2033 to March 2024, erratic rainfall patterns have intensified and expanded progressively across Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Namibia, as well as most of the Zambezi basin and southern Madagascar.

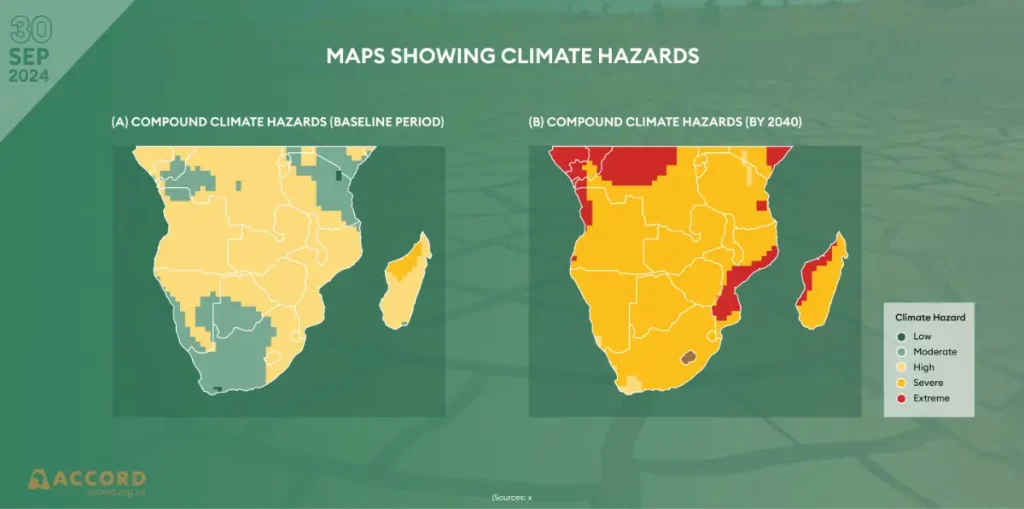

Due to persistent droughts, and the recent El Nino effect, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi are among the countries that have officially declared states of emergency in the region. According to the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), 17% of the region’s population or approximately 68 million people, are affected by El Niño-induced drought and need humanitarian assistance. Unfortunately, this situation is only projected to worsen and acute levels of food insecurity are likely to intensify amid drought conditions in 2025. By 2040, most countries are expected to face severe risks of compounded climate hazards.

Compound hazards refer to the hazard severity when accounting for the cumulative effects of heat, drought and flooding occurring simultaneously. The baseline period is for 1980 to 2010. In the baseline period, most of Southern Africa experiences moderate to high climate hazards, while by 2040, a substantial shift towards severe climate hazards is observed for most of the countries. Source: CGIAR FOCUS Climate Security.

A high percentage of Southern Africa’s population resides in rural areas, lives below the poverty line, and is immediately dependent on rainfed agricultural systems for food security and employment, thereby bearing the worst consequences of climate variability and extremes. Other segments of society also feel the knock-on effects of these climate-induced disruptions through economic shocks and job losses, food price spikes and reduced access to electricity, which in some countries, e.g., Mozambique, is hydrologically generated. Notably, a declining economy also implies less government revenue and pressure on basic services and environmental and social protection policies, which have dire repercussions on public safety precisely when the need for these government services increases. All these climate-induced disruptions not only pose significant socioeconomic and development challenges but also reshape relationships between and within communities, often making social cohesion and stability more difficult to maintain.

While this aspect has received little attention in research and policy circles so far, strengthening the resilience of Southern African societies amid an accelerating climate crisis implies that these gaps must be urgently addressed.

In order to draw attention to these social dimensions of climate change and to start to explore how best to prepare and manage the social impact of climate change, ACCORD and the CGIAR FOCUS Climate Security Southern African hub at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, with support from the Royal Norwegian Embassy to South Africa, organised a workshop in Pretoria on 6 August 2024. The workshop aimed to enhance understanding of the linkages between climate change, social cohesion, stability and peacebuilding in Southern Africa; to share best practices and experiences in addressing climate-related risks to social cohesion and stability; and to lay the foundations for regional multilateral strategies for integrated climate resilience and sustaining peace initiatives.

Migration is one of the ways in which some people adapt to the effects of climate change in Southern Africa, potentially bringing positive impacts on both home and destination communities by supporting livelihoods and protecting against economic insecurity.

Tweet

What do we know?

Developing effective strategies to prevent and mitigate the risks that climate variability and extremes pose to social cohesion and stability requires a collective understanding of the conditions under which these risks can emerge. To start building this evidence base, the workshop discussed and expanded on the findings from the joint work of the CGIAR FOCUS Climate Security team and ACCORD in engaging with local communities and national and sub-national stakeholders in Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

While the magnitude of climate change’s socially destabilising impact largely depends on the extent to which there are existing vulnerabilities related to water and infrastructure, social and political institutions, in the three countries, resilience and response capacities are (differently but) progressively being undermined in ways that decrease incentives for collaboration and peaceful co-existence. As a result, the likelihood of latent tensions to escalate or new ones to emerge can increase in the short or longer term. Regardless of contextual factors, these dynamics always play out indirectly through climate-induced stressors and shocks to food, land and water systems.

For instance, in the Southern Provinces of Zambia, competition over access and use of dwindling water resources has significantly increased over the past years due to failing rainfall patterns combined with limited knowledge of sustainable use of water resources and weak resource governance mechanisms. Thus, tensions are mounting between communities or between different water users in the same community, such as small-scale disputes and fights among women while queuing at boreholes, as well as between cattle herders because of disputes about who should get access and in what order. Conversely, in Zimbabwe’s Gwanda District, cattle rustling and conflicts over diminishing grazing and water resources have emerged between pastoralist communities, with some of those escalating into violence and fatalities.

Migration is one of the ways in which some people adapt to the effects of climate change in Southern Africa, potentially bringing positive impacts on both home and destination communities by supporting livelihoods and protecting against economic insecurity. However, even voluntary migration can create new challenges and amplify existing inequalities, especially for women and girls who are often left behind. At the same time, it can also lead to disputes and even small-scale conflicts in receiving areas between migrants and host communities over food, water and employment opportunities, as in the case of Harare and Bulawayo, to mention a few. Indeed, rural-to-urban migration contributes to the overcrowding of cities, straining health and public infrastructures and putting national and local authorities in a difficult position as they struggle to meet the basic needs of an increasingly growing population. Interestingly, in Zambia, the movement of farmers from the south up north to overcome climate-induced agricultural hardships is having a destabilising impact on destination communities due to clashes over cultural values and traditional practices in agricultural production and knowledge systems.

Extreme weather events, such as droughts and cyclones, are also forcefully displacing people, which implies less time for preparation and thus increased human security and protection risks, including potential tensions and higher exposure to natural and man-made hazards. For instance, in Northern Mozambique, climate-induced displacement further undermines adaptive capacities of populations already affected by conflict. Due to widespread poverty and lack of employment opportunities in the legal market, some persons, particularly youth in displacement settings, are thus joining non-state armed groups as, amongst others, an alternative way to make a living. This further complicates peacebuilding efforts in the Cabo Delgado Province.

Finally, the loss of agriculture-based livelihoods and resulting food and economic uncertainty are pushing people into harmful coping mechanisms; in Zimbabwe, this includes early marriage and girl child school dropout, reliance on illicit artisanal mining as an alternative source of income, as well as cattle rustling. Moreover, in urban environments, feelings of frustration and resentment against authorities are mounting due to shortages of electricity and maize, as well as food price spikes that challenge the capacity of the urban poor to afford basic commodities. These dynamics have been documented in a number of countries in the region, including Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

[T]he risks to social cohesion and stability are not yet adequately reflected in most national policy frameworks and strategies such as National Adaptation Plans (NAP) or other national climate change policies of the different countries in the region.

Tweet

Regional and national policy responses

The policy frameworks and strategies of regional bodies such as the African Union (AU), SADC and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) reflect the recognition of the threat of climate change. Their emphasis on mainstreaming adaptation, mitigation, and resilience-building measures, particularly in critical sectors such as agriculture, water, and energy, lays the basis for a comprehensive approach essential for sustainable peace, development and community well-being. However, the risks to social cohesion and stability are not yet adequately reflected in most national policy frameworks and strategies such as National Adaptation Plans (NAP) or other national climate change policies of the different countries in the region. In this context, the current efforts of the AU to develop a Common African Position on Climate, Peace and Security (CAP-CPS) provide a much-needed space to discuss the regional and context-specific risks that the impacts of climate variability and change pose to social cohesion and stability. It also aligns with the conclusions of the recently held Extraordinary SADC Summit, which urged Member States to be proactive and strengthen anticipatory action programmes to mitigate climate-related risks.

African policymakers and social organisations recognise that climate change is not only about mitigation and adaptation but that it also has social impacts that need to be managed. Governments and social institutions need to develop and invest in social protection strategies that can strengthen the resilience of communities at risk. It is not enough to react, for example, through disaster relief responses and by declaring states of emergency. It is important to proactively invest in resilience and adaptive capacity, including in social institutions that promote and sustain tolerance and social cohesion. Climate mitigation and adaptation initiatives need to be conflict-sensitive, i.e. they need to take the social context into account, avoid increasing social tensions, and instead become instruments for strengthening social cohesion and adaptive capacity.

In this regard, Zambia’s Green Growth Strategy, launched in February 2024 by the Ministry of Green Economy and the Environment and its partners, represents a promising example of moving away from purely technical climate change and development solutions to consider elements of sensitivity and adaptivity to contextual dynamics, particularly at the local level. This includes an explicit recognition of the peace-contributing potential of climate action and sustainable growth, as well as their possible unintended negative consequences, particularly when they do not account for existing or latent drivers of tensions.

Cedric de Coning is a senior advisor to ACCORD and a research professor with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

Siyaxola Gadu is a climate change specialist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, one of CGIAR’s institutes.

Shaun Kinnes is a junior research fellow in the research department at ACCORD.

Giulia Caroli is a climate, peace and security specialist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, one of CGIAR’s institutes.

Ashleigh Basel is a systems specialist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, one of CGIAR’s institutes.

Gracsious Maviza is a gender and migration scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT and the lead of the Southern Africa hub.

The workshop was organised with the support from the Royal Norwegian Embassy to South Africa. This work was also carried out with support from the CGIAR Initiative on Fragility, Conflict, and Migration. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders/.