A significant number of deaths of the elderly in Europe and the USA are associated with old age homes. There have also been distressing reports indicating instances of neglect, mistreatment and even entire facilities found abandoned by staff, scared from being exposed to infection. However, the global statistical picture does not necessarily represent the reality of COVID-19 in Africa. This article isolates three significant dimensions where the African elderly have been adversely impacted: denial of access to public health facilities, income evaporation, and living spaces under lockdown.

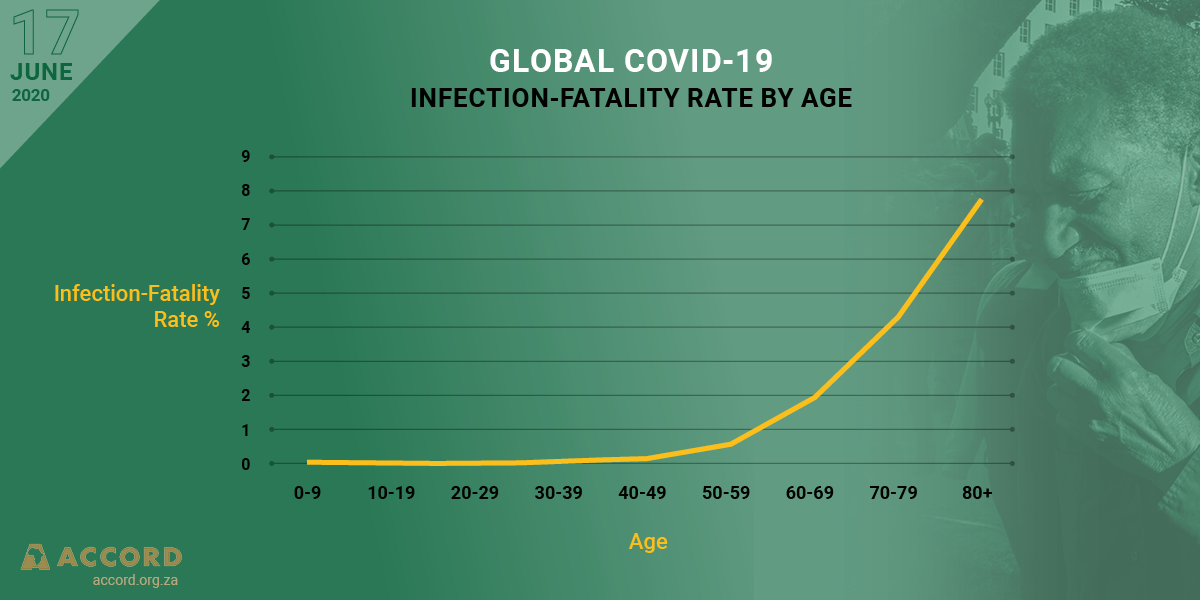

The elderly are most vulnerable to COVID-19, and it is thus important that the governments and agencies responsible for designing measures to prevent the spread of the virus take into consideration the impact of these policies on the elderly.

Tweet

Public health access

State responses to COVID-19 in Africa have included the immediate repurposing and prioritising of public health facilities towards fighting the pandemic. In practice, hospitals were ordered to prioritise COVID-19, and this has disrupted the access of elderly patients with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, dementia or cardiovascular strains. These are conditions that weaken the immune system, making it less able to fight off infections.

Income and livelihoods

A major feature of COVID-19 has been its impact on income, both in the formal and informal sectors. Its effect has been most evident in family links and informal trade. This includes remittances from the diaspora, as millions join the unemployed in areas where popular village or town square markets have been shut down, eliminating a key feature of the revenue stream of informal settlements.

By way of example, in South Africa – a country with a limited social welfare system – relative increases were made to grant levels with the advent of COVID-19 to try and alleviate the negative impact on income. However, a limited case study by Dr Gabrielle Kelly of the Samson Institute for Ageing Research, focusing on household experiences, offers us glimpses of the lifestyles of the elderly during the pandemic. In the findings, 87% of the elderly are using their pension social grants to support their adult children and their own children, therefore housing several generations. This is, in part, due to the country’s high unemployment rate. A total of 74% of over-60s live in households with two or more people, with only 16% living with spouses. For this community, the COVID-19 lockdown severely disrupted their relative mobility and independence, making them now entirely dependent on the social grant.

Living spaces under lockdown

Africa’s elderly continue to live in the community as well as in refugee camps, informal settlements and prisons, making them a constituency particularly at risk due to overcrowded conditions. Worse, in a typical example cited by HelpAge’s Catherine Caruso, COVID-19 has impacted the elderly in Mozambique who are still recovering from the devastating effect of Cyclone Idai, as well as hampering the ability of the NGO to access these people during the enforced lockdown. In African societies, it is uncommon to commit the elderly or even the disabled to institutional care. Instead, it is the family’s responsibility and an honour to look after their elderly.

The impact of COVID-19 on the psychological well-being of the elderly, manifested in increased cases of depression and dementia in the absence of regular medication, care and company, is unknown but likely to be significant.

It is thus important that the governments and agencies responsible for designing measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 take into consideration the impact of these policies on the elderly and honour their commitment to Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, which commits us all to Leave No One Behind.

Martin R. Rupiya is innovation and training manager at ACCORD.