The Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) announced the first case of COVID-19 in South Sudan in April 2020. Thereafter, a High-level Taskforce for COVID-19 was established to monitor and enforce the recommended measures by the World Health Organization. These measures included travel restrictions, social distancing, the decongestion of workplaces, partial lockdowns and increased levels of hygiene. However, the new situation presented additional strain on the already flimsy R-ARCSS. This was made worse by unprecedented flooding in many parts of the country, destroying many villages and towns and creating a humanitarian catastrophe in the face of a dwindling oil-based macro-economy.

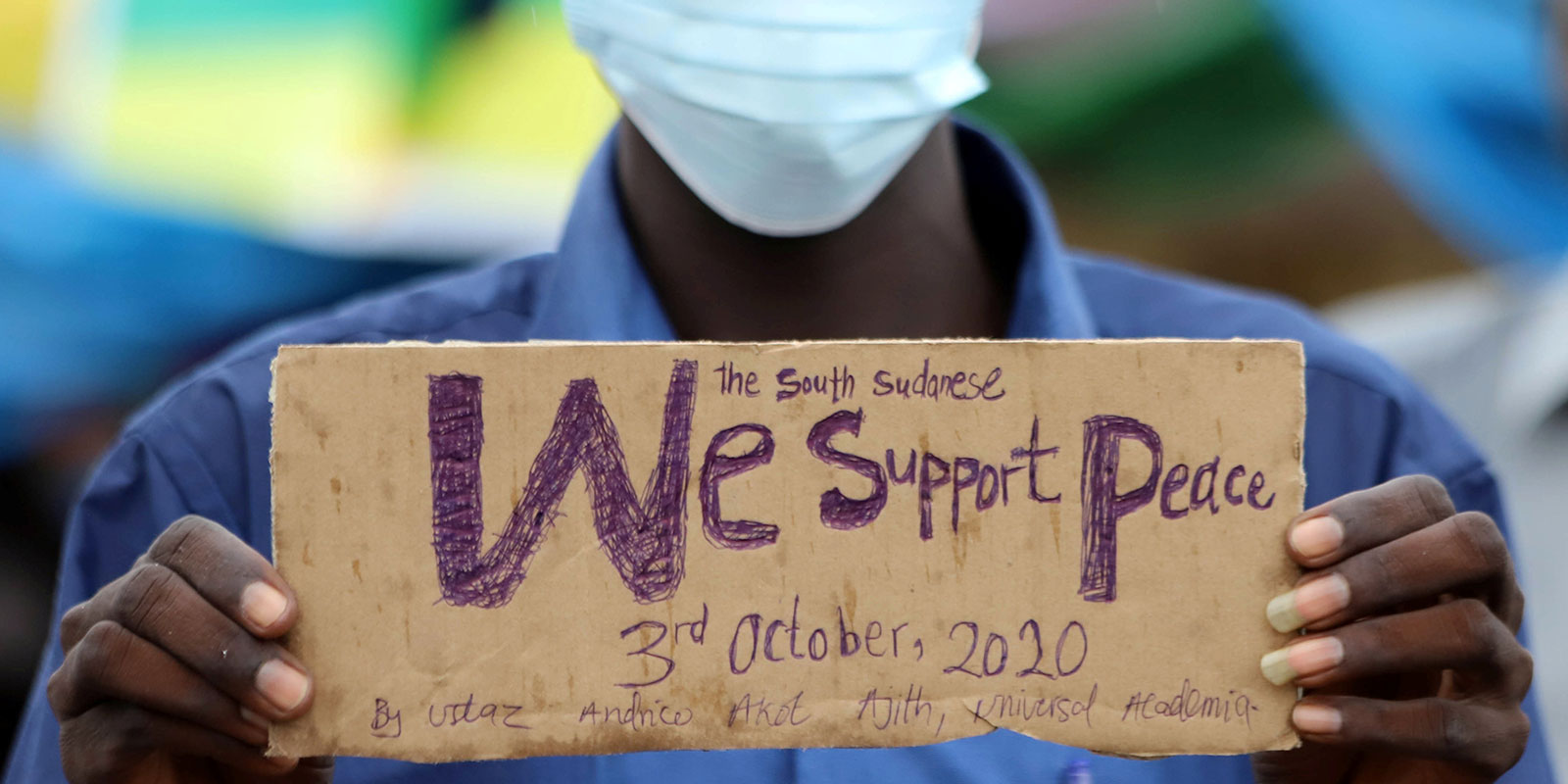

The effect that COVID-19 has on the delicate peace process in South Sudan should not be taken lightly. Good political will remains in high demand for sustainable peace and development in South Sudan. #C19ConflictMonitor

Tweet

To date, the number of cases of COVID-19 in South Sudan have reached over 3 003, with 59 deaths and 1 290 recoveries, and with limited humanitarian and developmental support to deal with the impact. The latest form of support was the approval of US$52.3 million by the executive board of the International Monetary Fund in the second week of November 2020. Under the Rapid Credit Facility for urgent intervention, it was recommended that the RTGoNU enforce budgetary discipline, revamp the balance of payments, improve delivery capacity and avoid deficit monetisation of the local South Sudanese pound (SSP) against international hard currencies. The purpose of the loan is to address the impact of COVID-19 as a priority, contribute to poverty reduction and enhance diversified economic growth. All these efforts should be accompanied by strict auditing, anti-corruption measures, integrity, transparency and accountability.

When looking at the impact of COVID-19 on the peace process in South Sudan, it is clear that the political leaders of the RTGoNU and the guarantors of R-ARCSS have used the pandemic as a suitable scapegoat on which to hang blame regarding the lack of significant progress. They have failed to concentrate on the merits of the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan (as amended in 2011), which would override all national legislation and legitimise the decisions taken in the public interest. They have not taken the lead to minimise the impact of the pandemic on the permanent ceasefire, security arrangements and reforms, as stipulated in Chapter II of the R-ARCSS. Instead, they have rushed the power-sharing without ensuring the completion of training and deployment of the necessary unified national armed forces, which includes the army, police service, security service, prison service, wildlife service and civil defence service. As a result of food shortages and other necessities in cantonment sites/barracks and training centres, soldiers have deserted or resorted to cutting down trees to sell as charcoal, as reported by the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Verification Mechanism. Furthermore, there has been no assessment, review, development or adoption of policies after the formation of the security and defence mechanisms.

The fragile security situation contributed to further delays in the establishment and reconstitution of the RTGoNU, as required in Chapter I of the R-ARCSS. When the first vice president, two vice presidents and a few national ministers tested positive for COVID-19 in May 2020, the meetings of the Presidency and the Council of Ministers had to be suspended for months. The reconstitution of transitional national legislatures, comprising 550 members for the Assembly and 50 members for the Council of States, also got stalled, with the old legislature remaining illegitimately operational. The judiciary was also not reformed to include an independent Constitutional Court, Judicial Reform Committee and reconstituted Judicial Service Commission. While nine governors were appointed (except in Upper Nile State), power-sharing in states and local government institutions among the parties was postponed.

The RTGoNU and African Union have also been slow to conduct stakeholders’ consultations and establish transitional justice mechanisms in accordance with Chapter V of the R-ARCSS, which calls for a Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing; a Hybrid Court of South Sudan; and a Compensation and Reparation Authority. Discussions on the parameters of permanent constitutional making and reconstitution of the National Constitutional Review Commission have not yet been organised by the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (R-JMEC), as required in Chapter IV of the R-ARCSS. The Political Parties Council and National Elections Commission have also not been reconstituted, as required in Chapter I. This impacts on multi-party and electoral management for the preparation of free, fair and credible elections at the end of the transitional period, with an outcome that reflects the true will of the people.

Towns and villages that have been badly damaged in the war have not been reconstructed, as required in Chapter III of the R-ARCSS. The US$100 million that was supposed to be made available by the RTGoNU could not be disbursed, and no donor conference has been organised for this purpose. Almost five million refugees and internally displaced persons of South Sudan could not be repatriated, resettled and rehabilitated, although some have returned home voluntarily. Also, dividends of peace economy and reforms, as detailed in Chapter IV of the R-ARCSS, have not yet trickled down to ordinary citizens, although some steps have been taken by the RTGoNU to establish the Public Finance Management Oversight Committee. Perennial food insecurity, lack of health infrastructure, paralysis of public institutions, unpaid salaries of civil servants, uncontrolled inflation, rampant insecurity and a myriad of other conditions have made the population desperate for international assistance, with no trust in the government.

The impact of COVID-19 on the delicate peace process in South Sudan should not be taken lightly. The associated stigmatisation, mistrust, insecurity, malpractices, violence, instability and tensions must be approached holistically so that the objectives of the R-ARCSS are kept intact. These objectives are to bring war to an end, restore security, facilitate humanitarian assistance, share federal power, encourage reconciliation, return displaced persons, enforce transitional justice, pursue institutional reforms, stabilise the volatile economy, develop a permanent constitution and conduct credible elections. There will come a time for the end of COVID-19, but good political will always be in high demand for sustainable peace and just development in South Sudan.

James Okuk is a senior research fellow at the South Sudan Center for Strategic and Policy Studies (CSPS) in Juba.