The mass movement of people provides a fertile ground for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, while it is important to note that many Mozambicans, particularly those living outside the capital Maputo, do not have the luxury of social distancing or working from home. Cabo Delgado’s vulnerability to violent extremism and additional human security threats such as natural disasters and other infectious diseases – e.g., cyclones, floods, cholera, and malaria – demands skilful coordination of responses. Thus, the pandemic presents an additional challenge for the Mozambican government and Humanitarian-Development-Peace (H-D-P) actors to develop effective approaches to sustain peace in an already fragile and vulnerable region.

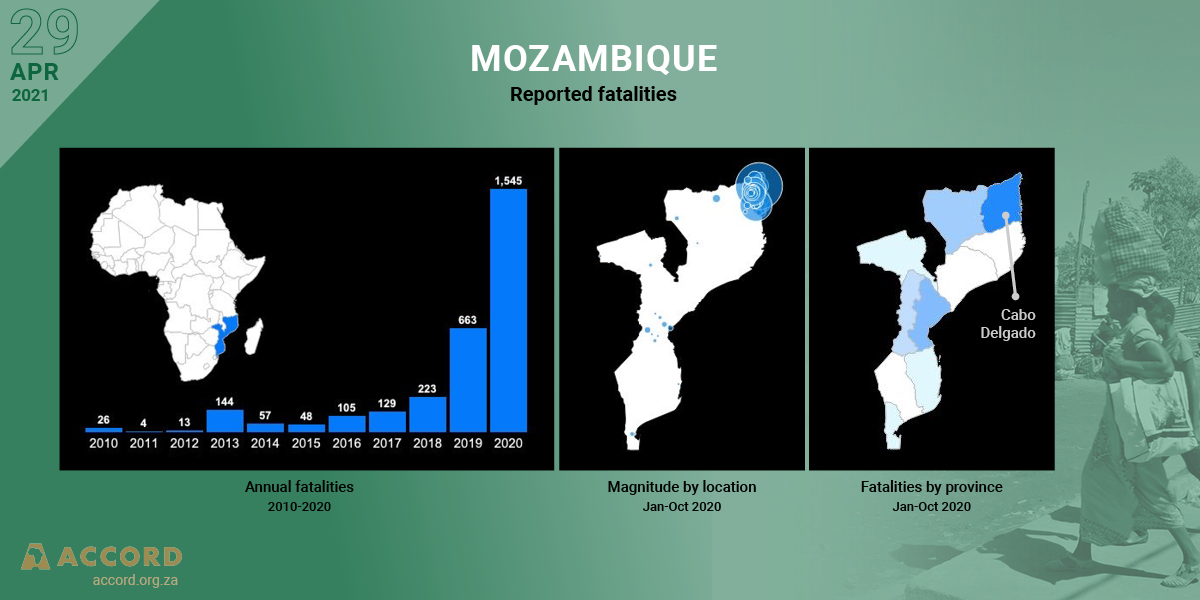

As the COVID-19 crisis started to spread globally, the security situation in Cabo Delgado also began to deteriorate rapidly. The Islamic insurgency focused first on isolated attacks on small villages. It turned into more extensive deadly attacks in major villages and towns, causing numerous victims and threatening existing state structures. The tactics and weaponry of non-state armed groups (NSAGs) operating in the province have also been evolving considerably, possibly with the support of external insurgents from the East Africa Corridor – Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia – providing organizational resources and armament. From March 2020 to March 2021, several waves of attacks were launched in several locations where government buildings, police stations, banks, and cellular communication infrastructures were targeted, exposing the state’s vulnerability in the region.

Pragmatic, adaptive, and holistic approaches focused on resilience have more chances to effectively address the interplay between violent extremism and human security threats, such as the #COVID-19 crisis.

Tweet

The Islamic insurgency in Cabo Delgado has subsequently developed into a pattern of violent attacks, propelling government responses to follow hard-security perspectives. At first, the Mozambican government responded by creating a regional military command in the province and pursuing security agreements with Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Uganda. It arrested suspected insurgents, closed mosques suspected of disseminating extremist ideologies, and passed new anti-terrorism laws. As these measures proved insufficient, the government’s hard-security approach welcomed private security companies, such as the Russian Wagner Group or the South African-based Dyck Advisory Group, to assist the Mozambican Defence Armed Forces (FADM – Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique) in their operations to counter the advance of NSAGs and regain lost territory. Other options in the same hard-security line have been considered. Portugal will send 60 military personnel for training actions with the FADM in a bilateral cooperation plan with Mozambique to help combat NSAGs in the province. The Troika Summit of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) was held in Maputo on 8 April 2021, with the top six leaders calling for “an immediate technical deployment” to Mozambique. Despite these initiatives, the insurgents continue to attack state structures and civilians in several locations with increased violence, causing numerous deaths and forcing thousands of civilians to flee in fear. The fact is that a military solution alone is deemed ineffective by some local scholars, including the historian Yussuf Adam who has been studying the region since the 1970s.

As violent extremism remains active and coexists with other human security threats in Cabo Delgado – including the spread of COVID-19 in the region – only a comprehensive and holistic approach combining security responses with development, peacebuilding, and preventive actions on several fronts – health, environment, inequality, poverty, and gender issues – will enable the government and international partners to address the root causes of violence in the region effectively. Researchers and practitioners seem to be divided on the origins and nature of violent extremism in Cabo Delgado. Some see religious extremism or even ethnic issues as the root causes of the conflict. Others see poverty, inequality, marginalization, and youth unemployment as some of the most relevant factors. Holistic perspectives will enable policy responses to secure natural resources infrastructure and focus on strengthening local and national government institutions, fostering functional state structures, and addressing the needs of local populations.

The Cabo Delgado conundrum will likely remain and aggravate unless further consensus among policy actors is reached on the need to develop holistic approaches based on resilience. This will enable local, national, and international practitioners to develop innovative coordination strategies to link development assistance, peacebuilding, and prevention and countering violent extremism (P/CVE). Here the coordination focus relies not only on the security dimension but also on the importance of fostering the resilience of local communities, state institutions, and international cooperation, integrating all responses through a whole-of-system approach.

As Cabo Delgado’s peace and security context demands security responses to be closely coordinated with H-D-P actions, the lessons provided by adaptive peacebuilding, adaptive mediation, and complexity theory present additional pathways to sustain peace in a fragile region affected by multiple threats. Adaptive approaches will enable peace to emerge from within, with adequate support provided by international partners. Adaptive peacebuilding methods such as participatory conflict analysis, and flexible, pragmatic, and evidence-based planning, implementation, and evaluation of context-specific responses will enable effective peace and security outcomes.

Cabo Delgado’s fragility and exposure to violent extremism, environmental and health threats, together with its geopolitical and socio-economic relevance, makes it a particularly sensitive context to destabilization and armed violence, possibly resulting in unforeseen consequences to Mozambique and the Southern African region. On one hand, hard-security approaches may respond to the sense of urgency in addressing violent extremism in the region but are ineffective in the short and long term to address its root causes. On the other hand, pragmatic, adaptive, and holistic approaches focused on resilience have more chances to effectively address the interplay between violent extremism and human security threats, such as the COVID-19 crisis. The focus on resilience highlights the need to assist local communities, state institutions, and international cooperation partners, to prepare for unknown threats and to learn how to live with them (adaptation), rather than focusing on the elimination of elements of uncertainty and complexity that will likely remain or re-emerge with time.

Rui Saraiva is a research fellow in the peacebuilding and humanitarian support team at the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ogata Sadako Research Institute for Peace and Development