Africa’s regional organisations and the United Nations (UN) have held a series of high-level summits to address the escalating situation in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which threatens regional stability. Since 2021, this largely ungoverned area has experienced a resurgence of armed groups, particularly the Rwanda-backed March 23 Movement (M23), which promotes Rwandan politico-economic and security interests rooted in historical context. In January 2025, the M23 seized Goma, the capital of the strategically significant, and mineral-rich, North Kivu Province, with little resistance from the Congolese armed forces (FARDC), and subsequently launched a military offensive into South Kivu. The M23 has attempted to establish a parallel civilian administration and expand mineral extraction in its areas of control. This reflects the narrative of “Greater Rwanda,” which envisions extending Rwanda’s territory beyond its colonial borders. The surge in violence in eastern DRC has resulted in significant loss of life and displacement and destruction of infrastructure, worsening an already critical humanitarian situation. Since 26 January 2025, over 843 people have been killed and more than 500,000 displaced, with at least 19 peacekeepers from the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) regional force (SAMIDRC) and the UN stabilisation mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) also killed.

Amid these dire circumstances, there is a summitry consensus on the urgent need for a peaceful resolution to the complex eastern DRC conflict. This article explores the role and strategic options of key stakeholders to stabilise eastern DRC: the UN, the African Union (AU) and its regional economic communities and regional mechanisms (RECs/RMs), specifically the East African Community (EAC) and SADC.

East African Community

The EAC aimed to address insecurity in eastern DRC by deploying a Regional Force (EACRF), with troops from Burundi, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda, to eastern DRC in November 2022, notwithstanding some EAC members’ competing vested interests. However, tensions regarding the EACRF’s mandate torpedoed the force. The EAC sought to use the force for peacekeeping efforts to facilitate the withdrawal of armed groups like the M23, while engaging in dialogue through the intermittent Nairobi Process facilitated by former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta. In contrast, the Congolese government did not extend the EACRF’s mandate, frustrated by its inability to offensively support the FARDC against the M23 and instead sought SADC’s assistance. In response to the deteriorating security situation in eastern DRC, an EAC extraordinary summit held on 29 January 2025 called on all parties to the conflict to cease hostilities and hold peace talks instead, urged the Congolese government to engage in direct dialogue with the M23, and proposed a joint EAC-SADC meeting. Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi, who had previously been averse to negotiating with the M23, did not participate in the EAC summit.

Southern African Development Community

In December 2023, SAMIDRC, comprising troops from Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania, was deployed following President Tshisekedi’s invitation. Its offensive mandate focuses on neutralising armed groups and the protection of civilians (POC) alongside the FARDC. SAMIDRC was meant to complement the Luanda Process, facilitated by Angolan President João Lourenço since 2022, to promote political dialogue between the DRC and Rwanda. Although a ceasefire agreement was reached in August 2024, subsequent talks collapsed by December due to bad faith from the parties involved and divergence over M23’s participations, with the M23 advancing rapidly, jeopardising the Luanda Process. SAMIDRC has faced logistical challenges despite support from the AU and UN and struggled to fulfil its mandate. On 31 January 2025, a SADC summit in Harare, Zimbabwe, condemned the M23 and Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) aggression, reaffirmed support for SAMIDRC and the Luanda Process, and called for a ceasefire process to ensure POC and flow of humanitarian aid. The summit also endorsed the proposal for a joint EAC-SADC Summit proposal.

African Union

The AU has also made efforts to address violence in eastern DRC. In 2022, the AU requested Angolan president João Lourenço to mediate between the DRC and Rwanda, initiating the Luanda Process. The AU has provided logistical and financial support to SAMIDRC. Following the renewed escalation in the DRC crisis and M23’s territorial expansion, the AU Peace and Security Council discussed the situation on 28 January 2025. The Peace and Security Council expressed deep concerns about the risk of an open regional war, reiterated the need for M23 to disarm and withdraw, and urged reconciliation and open dialogue among the parties. The AU has recognised the need to harmonise and coordinate existing peace initiatives. Therefore, the AU Commission (AUC) convened a Quadripartite Summit involving four RECs/RMs—the EAC, SADC, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR)—along with the UN in Luanda, Angola, on 27 June 2023. However, the lack of implementation of the resulting Quadripartite Mechanism, under the auspices of the AUC has perpetuated coherence issues, ineffectiveness and violations of both the Luanda and Nairobi processes.

United Nations

MONUSCO has supported the Congolese government in addressing security issues in eastern DRC, prioritising the POC, stabilising state institutions and supporting security reforms. MONUSCO has provided SAMIDRC with limited logistical and operational support according to UN Security Council Resolution 2746(2024). Despite its mandate, MONUSCO and SAMIDRC have struggled to curb the M23’s territorial expansion. On 21 February 2025, the UN Security Council unanimously condemned the M23’s actions and urged an immediate cessation of hostilities and a withdrawal from occupied territories, while demanding that the RDF stop supporting the M23. This was crucial as UN Security Council members have divergent views on the role of external forces. The A3 Plus group—comprising Algeria, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Guyana—has previously opposed any explicit mention of Rwanda, fearing it could undermine mediation efforts. The UN Security Council condemned the FARDC’s support for specific armed groups, particularly the ethnic Hutu group known as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), which was implicated in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide against the Tutsis and seeks to overthrow the Rwandan government. The UN Security Council also emphasised the need for all parties to reach an immediate and unconditional ceasefire in alignment with the demands of the EAC and SADC, urging the DRC and Rwanda to recommit to the Luanda and Nairobi peace processes.

The next strategic steps

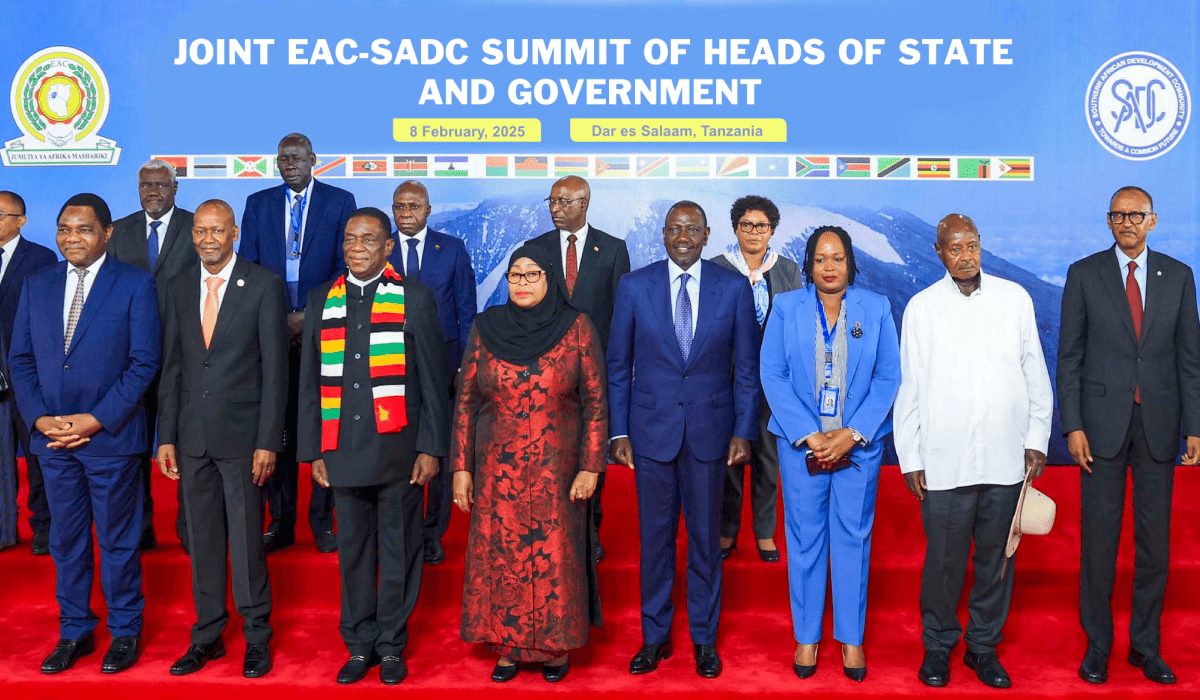

The historic joint EAC-SADC summit held in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on 8 February 2025 called for an immediate ceasefire, but so far this has had little effect. The summit demanded the “lifting of Rwanda’s defensive measures/disengagement of forces from the DRC,” advocating for the urgent consolidation of the Luanda and Nairobi processes. To stabilise eastern DRC effectively, the following assertive steps are imperative based on the recent flurry of high-level summitry by African regional blocs and the UN:

AUC, EAC and SADC

- The AUC, EAC and SADC Secretariats must develop a comprehensive framework to enhance coordination and integration between the Luanda and Nairobi processes, maximising their effectiveness;

- The AU, EAC and SADC must establish a Joint Coordination Mechanism to provide essential technical support, ensuring enhanced coordination and integration of the Luanda and Nairobi processes in close cooperation with other relevant RECs/RMs, particularly the ECCAS and ICGLR. SADC should deploy its Mediation, Conflict Prevention, and Preventative Diplomacy (MCPPD) architecture in this pursuit;

- The AUC, EAC and SADC Secretariats must set up robust funding mechanisms to support the peace initiatives in eastern DRC and implement regular reporting systems to ensure a unified decision-making process;

- The combined Luanda and Nairobi peace processes must engage all parties in the conflict. It is essential for all those with influence to make efforts to encourage those hesitant to participate in the peace talks to engage, fostering a comprehensive and inclusive approach to conflict resolution in the volatile eastern DRC.

UN

- The UN Security Council, as the ultimate guarantor of global peace and security, must unequivocally communicate its commitment to bolstering the merged Luanda and Nairobi peace processes, taking decisive actions necessary to optimise these initiatives and ensure effective implementation of any agreements reached;

- All 15 Security Council members must work collaboratively to achieve a shared understanding of how to secure peace and stability in eastern DRC, acting decisively to prevent any exploitation of divisions among members by parties to the conflict;

- The UN Security Council should guarantee that MONUSCO and SAMIDRC receive full support and adequate resources, strengthening the critical relationship between SADC, the AU, and the UN on peacekeeping to ensure the efficient execution of their mandates. The international community must consider punitive measures against armed groups that attack civilians, as well as SADC and UN peacekeepers;

- The UN Peacebuilding Commission, in collaboration with the AU and SADC, should assist the Congolese government to establish a strong state presence and effective governance in eastern DRC that is capable of administering the territory and countering threats against civilians.

Dr Gwinyayi A. Dzinesa is a senior faculty member of Africa University and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Pan African Thought and Conversation (IPATC), University of Johannesburg and Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR), South Africa. The views are those of the author and not necessarily those of affiliated institutions.