Sustained and growing environmental challenges combined with governance challenges over the years, and eventually exacerbated by the Libyan crisis, allowed for the growth and exploitation of inter-communal conflicts by violent jihadist groups which has now created instability in the Sahel.

A key lesson from the G5 Sahel experience for the #CaboDelgado situation is that it should not be viewed from a singular lens of violent jihadist extremism @SidikouMaman @g5_sahel_SE

Tweet

In response, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) authorised and mandated the deployment of the G5 Sahel Joint Force in 2017, as an ad hoc mechanism within the framework of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). So far, the joint force has undertaken 21 military operations in the eastern (Chad/Niger), western (Mali/Mauritania) and central (Burkina Faso/Mali/Niger) zones, resulting in relative stability for the thousands of civilians affected by the conflict.

As we watch yet another hitherto quiet part of the continent, Cabo Delgado in Mozambique, slowly becoming destabilised, one is compelled to attempt to draw lessons from our ongoing experiences in the Sahel, so that the political actors at the national, regional (SADC) and continental levels are better guided in their collective and coordinated response to the situation.

When carefully analysed, one can easily see some similarities between Cabo Delgado’s growing challenges with violent extremism and the case of the Sahel where extremist groups are exploiting the poverty, under-development, unemployment and poor basic social services to destabilise the region.

These similarities provide us with a number of lessons from the Sahel which must necessarily be applied in the response to the Cabo Delgado situation, which must not be viewed from a singular lens of violent jihadist extremism. And that is the very first, and perhaps most critical, lesson. It is important to understand that, like the case of the Sahel, which was for many years primarily viewed through that prism, and thus security centric approaches deployed in response, we have today, since the creation of the G5 Sahel in 2014, adopted a combined security cum development approach. It is one in which both development and security are not just theoretically linked in our mandate but given practical measures on the ground, including in our partnerships, especially in the Coalition for the Sahel for example, where we are combining the fight against terrorism with reinforcing the capacity of national defence and security forces, the return of the state with basic social services and justice, and both short-term and long-term economic development.

A further lesson from the G5 Sahel experience for the #CaboDelgado situation is to keep the military intervention focused and short, to avoid unintended consequences like civilian casualties @SidikouMaman @g5_sahel_SE

Tweet

It is therefore imperative that as soon as the Mozambican authorities, with their neighbours in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), are able to place a handle on the emergency of the most recent events in the area, that it considers a more holistic long-term response in line with the continental peace and security architecture while taking cognisance of the ongoing reforms in the African Union (AU). It would only be proper that whatsoever response mechanism is authorised and effected on the ground by the Mozambique authorities, SADC and the AU, that it is pragmatic and adaptive to address the causative factors that have permitted the entry of violent jihadi elements in the situation. Any militarised efforts must be primarily to create an enabling environment for the required political, governance and civilian stabilisation effort that should follow.

A second lesson draws from this, and that is the need to keep the military intervention determinedly targeted so that it does not last longer than required and then throw up challenges related to human rights and sustainability, especially in these times of limited resources. We have come to understand that the asymmetric nature of the fight against violent extremism may inevitably result in unintended consequences including a negative perception of our best intentions and efforts by the very citizens we seek to protect. In addition to the now widely acknowledged trainings on human rights and international humanitarian law for soldiers in these theatres, we must also include appropriately contextualised forms of follow-up mechanisms for incidents involving civilian casualties for justice and accountability. The Mozambican authorities and SADC must appreciate the critical importance of managing perception through an effective strategic communications programme, otherwise, wrong perceptions can be even more damaging and can drive people into the arms of the violent extremist forces.

Another lesson for #CaboDelgado from the G5 Sahel experience is to pursue a dual track security and development objective from the beginning, side by side, rather than wait for the one to follow the other @SidikouMaman @g5_sahel_SE

Tweet

Lastly, a most critical lesson which has to be considered remains at the strategic and political level, and this relates to the mandate that will guide the response to the Cabo Delgado situation. This is a most important factor considering that the situation could still be considered an emerging one and one for which political actors at the highest levels can draw applicable lessons from elsewhere in the Sahel, in Somalia and Afghanistan among others. As indicated earlier, the violence is the exploitation of some structural fault lines for which a solely militarised response may never effectively and sustainably address. Could this be a situation requiring a negotiated solution, including dialogue with the appropriate elements within the limits of applicable national, regional and continental frameworks? It is important for the mandating authorities to recognize the possibility and viability for dialogue and negotiations and to include this in the mandate for any intervention mechanisms.

In summary, it is important to underline from the onset that this intervention must not be anchored on a primarily military solution which could be drawn out, expensive and unsustainable. We must also be prepared to pursue a dual track security cum development mandate from the beginning by deploying, side-by-side, the required and appropriate capabilities rather than wait for the one to follow the other.

It is necessary to articulate a holistic and comprehensive mandate and mandated tasks that will address the drivers and grievances behind the conflict so that whatever mechanism is so deployed is appropriately resourced to effectively respond to the situation from the onset. This could also allow for a clear politically-led, comprehensive strategic framework, behind which partners can align, and mechanisms to facilitate coordination and track progress can be developed.

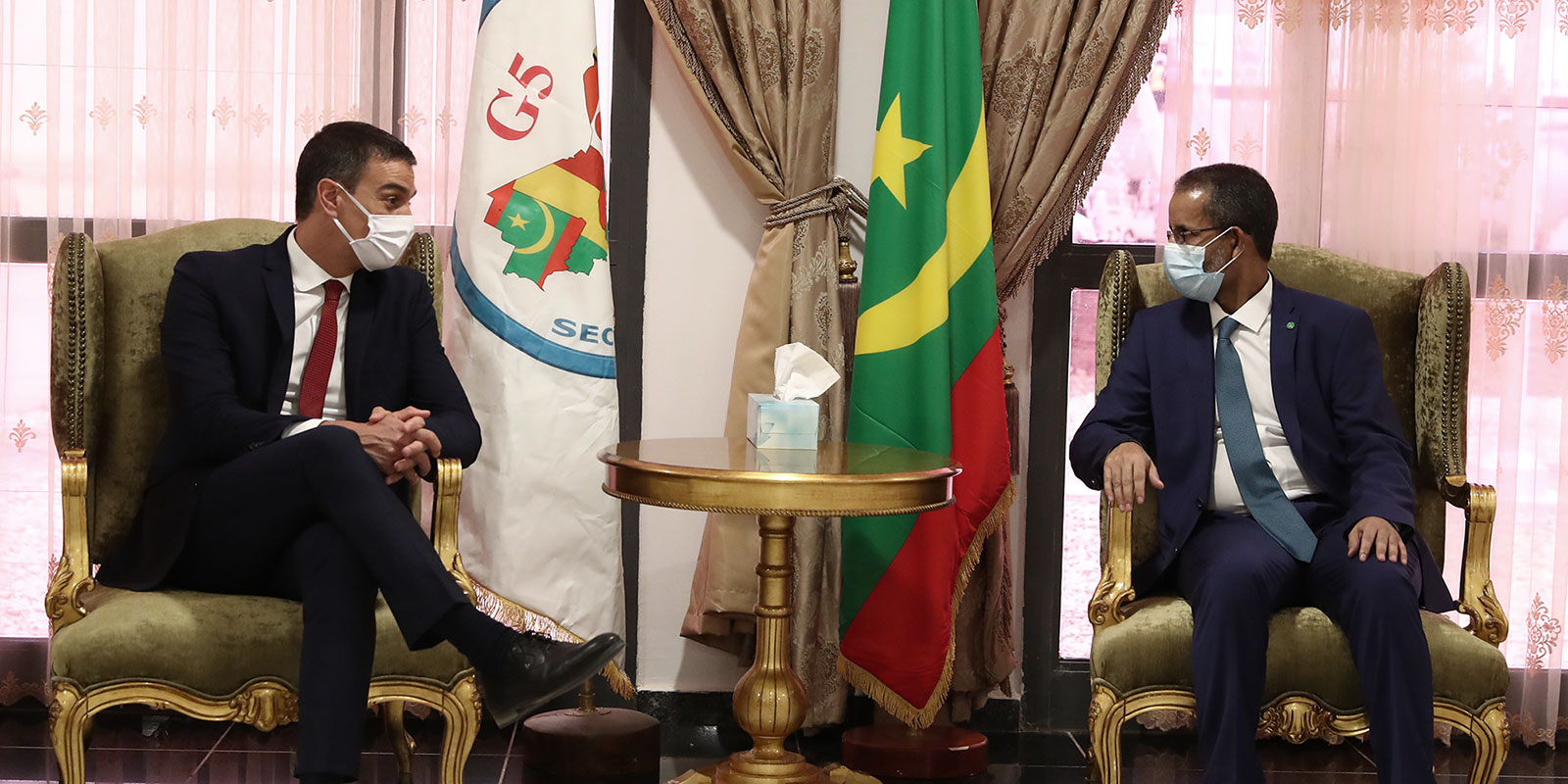

Amb. Maman Sidikou is the Executive Secretary of the G5 Sahel.