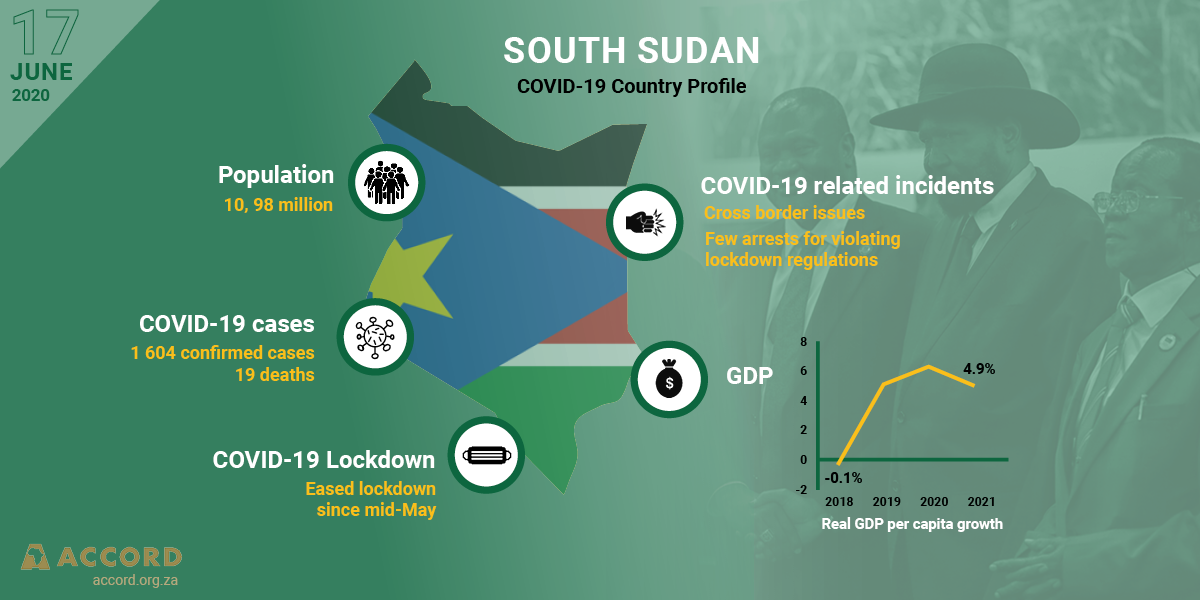

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 was recorded on 5 April 2020. Two months later, there are 1 604 confirmed cases, with 15 recovered and 19 deaths. In response to the first case, a COVID-19 National Task Force was established to coordinate a government-wide response to the pandemic. A nationwide curfew was put in place, the borders were closed and restrictions were imposed on interstate travel.

One of the ways in which COVID-19 had a negative impact on the implementation of the peace process was felt when the government decided to suspend the training of the unified forces as a precautionary measure – a decision that affected 29 000 combatants. The creation of a unified army was one of the core aspects of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), signed in 2018. Delays in the formation of the united forces will have a negative knock-on effect on the implementation of a number of other clauses of the R-ARCSS.

COVID-19 is negatively affecting the peace process in South Sudan. As a precautionary measure, the government has stopped the training of the unified forces. This will have a negative knock-on effect on the implementation of a number of other clauses of the R-ARCSS.

Tweet

Confidence dropped in the ability of the government to manage the crisis when it was reported that Reik Machar, first vice president and chairperson of the government’s COVID-19 task force; his wife, Angelina Teny, who is Minister of Defence and Veteran Affairs; and a number of other members of the task force all tested positive for the virus. However, after a second test, these leaders were cleared on 6 June. Before they were cleared, the president appointed a new chairperson to the task force, Fifth Vice President Hussein Abdelbagi, but he subsequently confirmed that he had also tested positive for COVID-19, on 27 May.

The other challenge facing South Sudan in its efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 is its porous borders. Cross-border control and surveillance mechanisms have been increased in an attempt to reduce the illegal crossing of traders, especially along the country’s borders with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda. Isolation centres have been established to quarantine those found to have illegally crossed the border. Instability in neighbouring countries is also resulting in refugees moving into South Sudan. For instance, the United Nations’ (UN) refugee agency is providing aid to refugees from the DRC who are fleeing the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Some internal movement is also of concern. For example, in May, authorities in Kapeota County, Eastern Equatoria State, detained and quarantined 54 people travelling from Juba to Kapoeta.

The spread of COVID-19 in South Sudan is adding further stress to existing humanitarian challenges. Before the advent of COVID-19, the sub-region suffered from an invasion of locusts, and projections then were that 5.5 million South Sudanese would go hungry without humanitarian assistance. The situation is compounded by the escalation of local community violence in certain parts of the country, with 450 incidents recorded between January and May 2020. The closing of borders to stem the spread of the virus has also created shortages of basic goods in some border areas between South Sudan and Sudan, such as in Aweil East County in Northern Bahr el Ghazal. As a result of these shortages, and with South Sudan being a landlocked country, the government decided to reopen the country’s airspace. The economic outlook was worsened by the drop in global crude oil prices, which is the biggest generator of revenue for the government, accounting for 98% of the state’s budget. However, the World Bank last month approved a grant of USD40 million to provide income security to the most vulnerable households.

COVID-19 has also had an impact on the role of the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). The first few cases of COVID-19 in South Sudan were among UN international staff, and the UN has implemented a number of measures to ensure that its peacekeeping missions do not become vectors for the spread of the disease. The UN froze all rotations and movement of staff, and all non-essential staff were asked to work from home or their UN accommodation. Despite these measures, government forces established checkpoints outside UN compounds in several locations to stop UN movements. These checkpoints were subsequently removed.

In addition, the virus has had an impact on the approximately 150 000 people sheltering in UN protection of civilian (POC) camps. In May, two positive cases were reported in one of these sites near Juba. The possible increase in the spread of the virus within these sites is a cause for concern, and both government and the UN have called on residents to return to their homes. UNMISS has also taken several steps aimed at supporting the government to deal with the spread of COVID-19, including engaging in information campaigns to ensure that the general public is better informed about the pandemic and the protocols relating to the quarantine measures imposed by the government.

The spread of COVID-19 in South Sudan has had a negative impact on the implementation of the peace process and placed further stress on an already dire humanitarian situation.

Tweet

Although the overall number of confirmed cases is still relatively low, the spread of COVID-19 in South Sudan is raising concerns because of limited public health facilities, an already dire humanitarian situation, an increase in communal clashes and a fragile peace process. On the other hand, a youthful population and limited movement inside the country due to poor infrastructure may slow down and limit the spread of the disease. The city of Juba and other areas where people are living in close proximity, such as the POC sites administered by the UN, are high-risk areas that require heightened quarantine measures.

Neyma Mildred Mahomed Ali is a postgraduate student at the University of Glasgow in the field of security, intelligence and strategic studies (IMSISS) and a member of the university’s Security Distillery Think Tank, where she is responsible for coordinating partnerships in the Outreach Department.