The health crisis

At the beginning of the year, COVID-19 infection rates were minimal and confined to a few countries in Africa. Yet, while it took about five months to reach 500 000 COVID-19 cases, it only took another month for that number to double in Africa. South Africa accounts for about half the confirmed cases on the continent and almost half of the reported deaths. But the rest of the continent is not spared – it may just have poorer data, testing and recording.

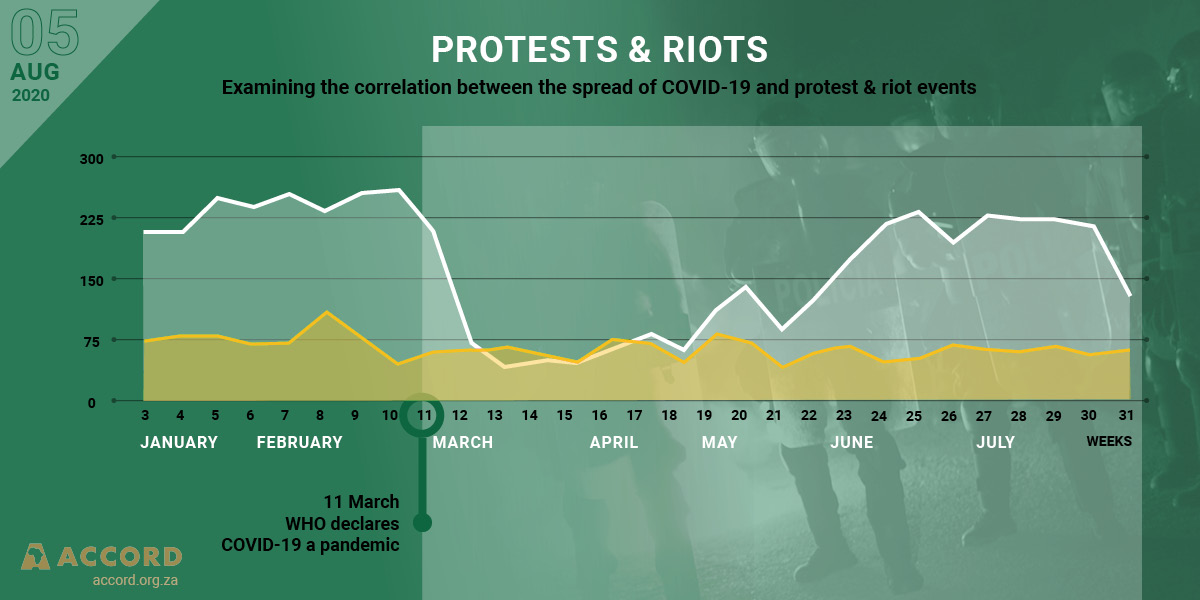

Protests have already rebounded to pre-pandemic levels in many countries, and can be expected to surge over the next few months as long-standing grievances over socio-economic inequalities and demands resurface.

Tweet

Some hoped that Africa would be relatively spared from the pandemic. Yes, poor health and testing facilities do not work in Africa’s favour, but the continent has also had experience with epidemics. Furthermore, it has demography and geography on its side. The continent’s youthfulness was expected to be an advantage – and the relative isolation of rural areas was hoped to slow transmission. And ‘only’ about 2% of Africans diagnosed with COVID-19 have died, which is half the global average. There may be several explanations for these relatively good numbers: early lockdowns, sparser populations and possibly extra protection because of people’s immune systems already being bolstered by previous battles against diseases. At the same time, the numbers should be treated with caution, both because of the delay between diagnosis and death, and because only a few African countries keep good cause-of-death records. And whilst there is currently optimism, the worst may still be coming.

The socio-economic and political spillovers of the health pandemic

The socio-economic and political waves following the virus are still to hit full force and will affect millions of people. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the first economic effects are coming in three waves: lower trade and investment from China, which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned about already in February; a demand slump associated with the lockdowns in Europe and the OECD; and a continental supply shock affecting domestic and intra-African trade.

The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects (June 2020) forecasts a 5.2% contraction in global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020. Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to contract by 2.8% and North Africa by 4.2%. This bleak outlook is subject to great uncertainty. Should the COVID-19 outbreaks persist, restrictions on movement be extended, etc., the recession could be deeper. Prior to COVID-19, the continent had already experienced a slowdown in growth and poverty reduction. In 2019, Africa’s GDP growth was already insufficient to accelerate economic and social progress and reduce poverty. The new realities are expected to tip tens of millions of people back into extreme poverty. The United Nations (UN) estimates that nearly 30 million more people could fall into poverty, and the number of acutely food-insecure people will significantly increase.

Political spillover and instability

Not only is the health pandemic itself increasing the chances of instability on the continent by increasing issues such as unemployment, inequality and problems with access to justice. Some political responses to the pandemic are also increasing tensions and heightening the risk of social unrest and conflict. In some countries, governments are accused of using the crisis to clamp down on the opposition, or on criticism. In other places, it is opposition parties that are accused of unfairly discrediting government actions. Already ongoing conflicts are continuing, in spite of the virus and the UN Secretary General’s call for a global ceasefire. And attacks by violent extremist groups are continuing – or, in some cases, increasing. In addition, more than 20 countries in Africa were scheduled to hold elections in 2020. Around half of these countries have delayed their elections, running the risk of heightening tensions, such as in Ethiopia.

According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), while Africa has experienced among the sharpest decrease in demonstrations, other types of violence have increased substantially, such as interpersonal violence and mob violence. The general reductions in political violence and demonstrations are also expected to be short-lived. The potential for more confrontation is high as lockdowns are lifted and the economic spillovers are being felt more heavily. COVID-19 is a political crisis as much as a health and socio-economic crisis.

African countries will face multiple blows. The lockdowns and wave of economic problems following the collapse in supply chains and commodity prices have hit both formal jobs and the informal sector hard, cutting people’s income where they have nothing else to fall back on. There is also an emerging crisis of subsistence, due to Africa’s lack of self-sufficiency in food. There is a high risk that more and more Africans will fall into poverty. And anger may mount among youth at the lack of economic opportunities, and what in many countries is seen as a lack of political responsiveness to their problems.

Sub-Saharan Africa had already seen the largest increases in anti-government demonstrations in the world between 2009 and 2019, with significant mass protest movements in Sudan, South Africa, Zimbabwe, South Sudan and Ethiopia. Now, in the face of COVID-19, people in Kenya mobilised on social media in response to President Uhuru Kenyatta’s early handling of the pandemic. In Malawi, civil unrest followed plans of a national shutdown. And in South Africa, there has been similar unrest, with thousands of people demanding aid. These developments portend greater danger for overall peace and stability across the continent – not only in previously recognised fragile states, but also in many other countries now seeing fragilities appear.

Several African countries are currently facing a ‘perfect storm’ of risks that could lead to unparalleled civil unrest in the second half of 2020, according to the Civil Unrest Index Projection from Maplecroft. Protests have already rebounded to pre-pandemic levels in many countries, and can be expected to surge over the next few months as long-standing grievances over socio-economic inequalities and demands resurface. The risks of internal conflicts spilling over into external conflicts are also high within an added changing geopolitical landscape.

The threats to domestic stability that we now face have few parallels in modern times, both in magnitude and type. With the goals of peace, justice and inclusion (SDG16+) being enablers of other development goals, this also puts the whole Decade of Action towards 2030 in jeopardy. Yet, as the pandemic tests the resilience of Africa’s democratic institutions, it also provides opportunities for progress. We have seen authoritarian crackdowns on the continent during the pandemic, but also democratic resilience. If African leaders manage to respond to this crisis with redistribution, good governance, a fight against corruption and improving people’s access to justice, the pandemic may give us hope for the future. If not, we are in for a long and tough haul.

Liv Tørres is director of Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, NYU-CIC and a visiting professor at the University of the Witwatersrand.