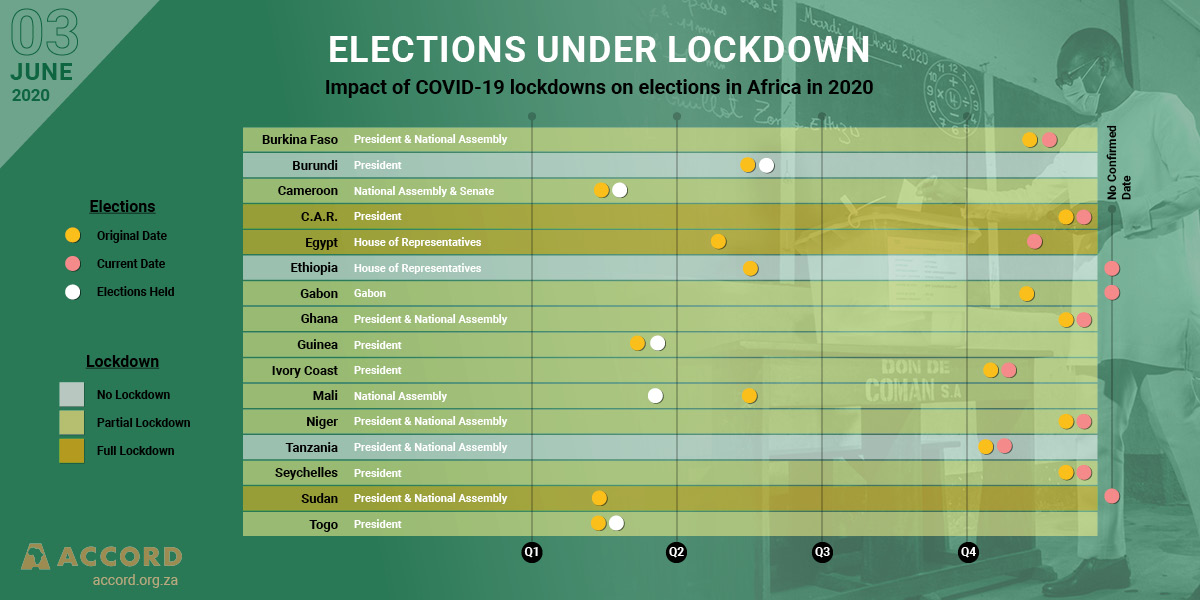

From Ethiopia, where the election has been postponed, to Guinea, where a constitutional referendum and parliamentary election were held despite the pandemic, a common pattern has emerged. The pandemic and the measures to contain it have given room to some leaders – already facing stern challenges from their opposition – to alter electoral calendars or restrict opposition activities where elections are held.

Postponing elections due to COVID-19, without building consensus raise concerns about motives. As the pandemic tests the resilience of Africa’s democratic institutions, it also provides lessons and opportunities for improvement and reform.

Tweet

Benin, Burundi and Guinea went ahead with elections, in which campaigning activities were severely restricted due to COVID-19 measures. Some of these governments ignored warnings against carrying out the elections from organisations such as the African Union (AU) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

During Benin’s recent local election, held on 18 May, candidates were barred from organising rallies, and campaign activities were restricted to posters, billboards and media appearances. Even though the opposition called for postponement and boycott due to concerns over the spread of COVID-19, the government went ahead with the polls. This election also took place in a climate of constrained political activity in the absence of key opposition parties, which were barred from participating.

In Burundi, even though the government indicated that it would allow international observers to monitor its presidential election of 20 May, it insisted that anyone travelling to the country would spend 14 days in quarantine before commencing their work. Further concerns expressed by the WHO against the election led to the expulsion of its officials from the country. The election was further marred by accusations and complaints from the opposition that access to social media sites were blocked on the day of the poll.

In Guinea, after postponing a constitutional referendum and parliamentary election at least four times over the last year, the government went ahead to organise the polls on 22 March. The elections were held after international observers – including the AU – indicated they would not be able to send observers due to public health concerns. The opposition movement, National Front for the Defense of the Constitution, which had boycotted the constitutional referendum, faced harassments and repression under the enforcement of emergency laws. While the government advised voters to observe public health regulations at polling centres, they denounced opposition protests as undermining those regulations.

Other countries decided to postpone elections due to COVID-19. However, without building consensus with the political opposition on such decisions, concerns are mounting about motives of buying time, or prolonging tenure for already unpopular leaders or those whose mandates may be ending soon.

Long before the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Uganda, rumours abounded of plans to postpone the elections due in 2021. Amidst these rumours, a private citizen petitioned the High Court to suspend all elections in the country for five years because “the threat of coronavirus will affect election monitoring due to restrictions on immigration that will affect election observers who are necessary in ensuring free and fair elections”. While the petitioner may have a genuine concern, his call for postponement for five years – a full presidential term – raises concerns about his real motive. In May, President Yoweri Museveni suggested that plans might go ahead to postpone the elections, when he said: “To have elections when the virus is still there… It will be madness.”

Ethiopia and Liberia face similar dilemmas, as they are both due to hold parliamentary elections later this year. In Ethiopia, the government has indefinitely suspended the polls due to COVID-19, and the current prime minister and his new Prosperity Party plan to stay on until elections are held. But the opposition has criticised the move, and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (previously part of the ruling coalition) has threatened to continue with elections in the Tigray region. The government also rejected calls by the opposition for an interim administration when the government’s tenure expires on 5 October. Failure by the Ethiopian government to generate consensus on such a crucial election and set out a way forward in the event of a postponement after October risks further tensions in a country already dogged by ethnic political divisions and violence.

In Liberia, long before COVID-19, there were concerns that due to lack of funding, the government had plans to postpone a constitutional referendum and elections due in October for 15 senators whose tenure expires in January 2021. In May, the National Elections Commission (NEC) stated that it was unable to hold the elections in October due to financial and COVID-19-related constraints. Opposition political parties have already rejected this proposal and insist on going to the polls in line with the constitution. But after being defeated in major legislative by-elections in the last two years, the ruling Coalition for Democratic Change seems unprepared for election this year. While a postponement might be in the interest of the government – which seeks to buy time both to raise more revenue to finance the elections and to remake itself amidst growing public disenchantment – it could lead to a major constitutional crisis at a scale the country has not seen before. But the lessons learnt when the country dealt with a very similar situation during the Ebola epidemic in 2014 could provide guidance in adverting any potential crisis and make way for peaceful and credible elections.

These developments portend greater danger for overall peace and stability across the continent, particularly in fragile states like Burundi, Guinea, Ethiopia and Liberia. Governments emerging out of this pandemic may face deeper crisis of legitimacy, and public reaction in the form of street protests are likely to trigger violent repression and instability in many countries.

As the pandemic tests the resilience of Africa’s democratic institutions, it also provides lessons and opportunities for improvement. Therefore, beyond COVID-19, African governments must initiate constitutional reforms to address the many shortcomings of their democracies. These reforms must, among others, make provision for the holding of elections and the seamless management of transitions, or the negotiation of political settlements during crisis situations. These reforms will not be the silver bullet to the many problems of democratic governance in Africa, but they will be crucial to averting or minimising the risks of future crisis – disease or political.

Ibrahim Al-bakri Nyei is a PhD student at SOAS University of London and an Adam Smith Fellow in Political Economy at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University. He tweets at @ibnyei.