Mali’s conflicts have eddied from the northern desert to the central Sahelian region, pulling in one identity group after another. Multiple military campaigns have been launched against armed Jihadist groups, while peacekeeping forces are tasked with protecting civilians and abating community-based violence. The extent to which climate matters here is sometimes debated, but NUPI and SIPRI’s fact sheet on Climate, Peace and Security in Mali finds that the effects of climate are currently changing, and will increasingly, accentuate the social, political and economic vulnerabilities that underlie Mali’s violent conflicts.

Mean annual temperatures in Mali have increased since the 1960s and are expected to climb by 1.2°C to 3.6°C by 2060; particularly in the southwest, centre and north. Average annual rainfall varies from north to south, but rainfall decreased overall in the 1900s. Extreme droughts have occurred in the recent past. Future precipitation is projected to be more erratic, affecting seasonal rainfall patterns and increasing the risk of drought and floods.

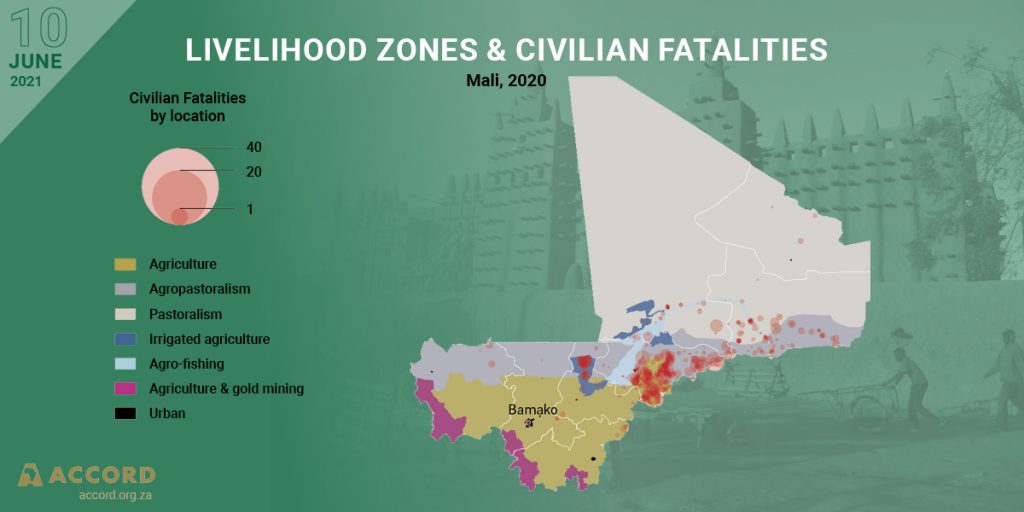

Mali is familiar with extreme weather but its exposure to climate change is compounded by factors that affect the ability of society and government to mitigate and adapt; for example, high reliance on natural resource-based livelihoods and limited livelihood alternatives, and increasingly concentrated and intensive natural resource use. No surprise, then, that the effects of climate change first and foremost affect farmers and herders, who make up about ca. 80% of livelihoods in Mali.

The fertile Inner Niger Delta provides farming, fishing and grazing opportunities, accounts for ca. 8% of national GDP and sustains ca. 14% of the population; but its water resources have been diminished by the combined effects of intensive up-stream water use and dams, and drought. As a result, people are leaving in search of alternative incomes, while farmers and herders increasingly clash over land and water resources. The projected effects of climate change on water and pasture availability in the Delta may increase the pressure on local resources and on local livelihoods.

On the one hand, groups that rely heavily on natural resources are vulnerable to extreme weather. On the other hand, their livelihood security is also affected by violent conflict. The effect of conflict makes communities, especially vulnerable groups, less able to invest in building climate resilience. Migrant pastoralists are a case in point. Seasonal migrations have become more dangerous, due to the operations of armed groups and military forces. Cross-border migration, enshrined in the ECOWAS Protocol on Transhumance, comes at the price of harassment and extortion by security forces. Young Fulani herders are targeted by Malian forces, local militias and communities for their real or perceived association with Jihadist armed groups.

When the effects of climate change interact with factors like weak governance and political instability, food and livelihood insecurity, marginalisation and inequality, it can create opportunities for armed groups to boost recruitment and support. The Macina Liberation Front/Katiba Macina in central Mali has exploited issues like land rights and the marginalisation of Fulani herders to draw local support. The group has recruited heavily from Fulani pastoralist youth. Other armed groups in north and central Mali have capitalised on government absence by mediating resource disputes, providing protection and support to farmers and herders, and defining rules for livestock migration.

Inequalities are a recognised driver of conflicts and they also influence how climate change affects individuals and communities. When climate change affects some groups more than others, there is a greater risk that it feeds into the grievances that drive conflicts. National agricultural policies already prioritise access to land and water for sedentary farmers over migrant herders, compounding environmental strains and fuelling farmer-herder conflicts; even in relatively resource-rich areas like the Inner Niger Delta and the Sikasso region. These conflicts are accentuated by local corruption, excessive fees levied on herders for pasture usage, and national gendarmerie participation in protecting farmers’ land access.

In Mali, women comprise ca. 40 per cent of agricultural labour but less than 10 per cent of landowners. Many rural women depend on garden produce and small livestock for sale in local markets, rendering them highly exposed to the effects of climate change and conflict. The potential of raising income also becomes harder as women’s access to markets for selling goods has been restricted by conflict, undermining livelihood security and resilience. However, some women in Mali are finding solutions, such as collaborating rather than competing for resources through women-led initiatives like agricultural associations for soliciting financing from NGOs.

The Malian government and its partners can use conflict resolution, peacebuilding and long-term development strategies to address the issues where climate change entails conflict risks, for example by:

- Improving analysis, collaboration and coordination, and strategic coherence on climate, peace and security risks. Risk management should prioritise dialogue, governance and development interventions for enhancing resilience to climate change across government, civil society and local communities. To avoid securitising climate, peace and security risks, actors should move away from a threat narrative and invest in prevention, resilience and preparedness.

- Developing policy frameworks for addressing resource management and agricultural development and changing migration and mobility patterns. These should support climate mitigation and adaptation strategies that reinforce the resilience of natural resource users, especially farmers and herders, and prevent violent conflict.

- Working with civil society to boost participation and leadership among women, girls and female-headed households in climate and conflict analysis and decision-making on gender-sensitive climate adaptation strategies.

Kheira Tarif (SIPRI) and Anab Ovidie Grand (NUPI)) both support a collaborative project undertaken by NUPI and SIPRI to generate evidence-based information on a select number of countries on the UN Security Council agenda. The Climate Change, Peace and Security Fact Sheet on Mali is available here.