The COVID-19 pandemic has created new opportunities for China to cement its engagements in Africa. Chinese diplomats have cast Beijing’s medical assistance as an example of “friendship,” “sincerity,” and above all, “solidarity,” or tuánjié [团结] to answer what they view as Western campaigns to “smear China.” Expressions of tuánjié (solidarity) also flowed in the other direction, however. At least 30 African nations sent financial and material assistance to China—initiatives that largely went unnoticed.

Global public health has always been a been key element of China’s foreign policy, especially in Africa. China dispatched its first CMT to Africa in 1961 and has since deployed over 20,000 civilian and military CMTs to 51 countries.

Tweet

This support included 10 tons of medicine from Egypt, $2 million from Equatorial Guinea, a plane-load of aid from Algeria, and PPE from Ghana, Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia. Even war-torn Somalia sent aid, as did students from Kenya’s Mathare slum, dispelling the misconception that African actors lack agency in their dealings with China. Cast in this light, China’s role is partly focused on reciprocating these acts of goodwill from Africa, another popular talking point.

Africa was the only region that Chinese President, Xi Jinping, dwelt on when he addressed the 73rd World Health Assembly in May 2020. He announced a $2 billion commitment for the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) COVID-19 response, “especially in developing countries.” In June, he pledged more pandemic-related support to Africa at the China/Africa Summit on Solidarity Against COVID-19. This included debt relief, equipment, vaccines, education and training, and technical expertise.

However, China’s message of solidarity is not without problems. In March 2020, numerous videos of Africans being evicted, blocked from hotels, and refused entry into restaurants emerged during a resurgence of COVID-19 in Guangzhou. The Group of African Ambassadors in Beijing wrote a strongly-worded letter to Foreign Minister Wang Yi over “racism, discrimination, and stigmatisation” against their citizens, many of whom received Chinese government scholarships. Many African countries summoned Chinese ambassadors to express outrage and demand action, exchanges that continued for several months. After a period of intensive crisis management—mostly behind closed doors—the two sides appear to have agreed to present a united front.

In October, 50 African diplomats and senior officials visited Chinese pharmaceutical giant, SinoPharm, at the invitation of the Africa Department of China’s foreign ministry. A key outcome was a commitment by SinoPharm and another Chinese pharmaceutical, Sinovac, to establish COVID-19 vaccine production lines in Africa, starting with Egypt and Morocco. In December, Chinese and African leaders gathered again, this time in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to attend the ground-breaking ceremony of the first phase of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa-CDC) headquarters, which will be constructed by China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation.

China is also following a strategy

Beyond narratives of solidarity, China’s role in COVID-19 in Africa is also part of a larger strategy, or zhànlüè, [战略]. In January 2020, Xi Jinping formed a “Central Leading Small Group for Countering the Coronavirus Epidemic.” Leading Small Groups (LSGs) are the nerve centres of China’s decision-making system, responsible for strategy and policy coordination across the state, government, party, and military. The COVID-19 LSG assembles China’s top foreign policy architects including Premier Li Keqiang; Wang Huning, a key advisor to Xi and well-known by African leaders; foreign minister Wang Yi, and Vice Premier Sun Chunlan; both of whom have led high-level visits to Africa; and Huang Kunming, the Head of the Communist Party of China’s Propaganda Department. Premier Li, and Wang Huning also sit on the 7-member Politburo Standing Committee, China’s highest leadership body. This illustrates the importance China attaches to the external elements of its COVID-19 strategy.

China has also committed itself to prioritising vaccine access, a major AU policy goal that is likely to be a top agenda at the forthcoming FOCAC Summit in Dakar, Senegal.

Tweet

None of this is new

Global public health has always been a been key element of China’s foreign policy, especially in Africa. China dispatched its first Chinese Medical Teams (CMT) to Africa in 1961 and has since deployed over 20,000 civilian and military CMTs to 51 countries. In any given year, between 30-40 CMTs are operational in Africa, each with a size of between 24-100 personnel on 1–2-year rotations. The difference this time around is that they are operating in a climate of heightened mistrust between China and Western powers, and amidst a global pandemic whose first epicentre was in China itself. This changes the calculus of China’s leaders considerably as they were heavily criticised in international circles for mismanaging the initial outbreak and failing to share crucial data with other countries.

Shortly before the World Health Assembly in 2020, China’s security agencies presented Xi a report warning that on account of COVID-19, anti-China sentiment was at its highest since the global backlash stemming from the 1989 Tiananmen student protests. This partly explains why China has deployed all tools of statecraft to project itself as a solution to the crisis, especially in Africa. It has focused on four objectives:1) Counter and dispel negative perceptions, 2) Signal China’s role as a global leader providing solutions to global problems, 3) Reposition China as a partner of choice, and 4) Build relationships that create a more conducive environment for Chinese leadership beyond the pandemic.

A Three-Pronged Approach

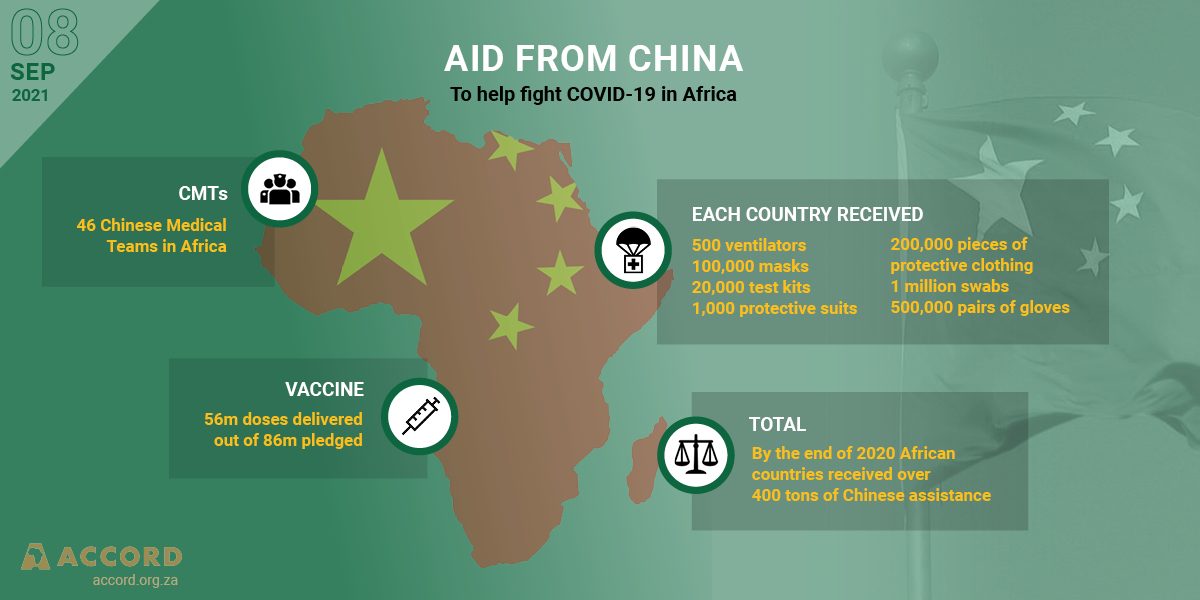

Deliveries of masks, medical, and protective equipment: With the COVID-19 LSG playing a coordinating role, China re-focused its CMT programme on the pandemic. By early March, China’s National Health Commission had scaled up its CMTs in Africa to 46. In mid-March, the Jack Ma and Alibaba Foundations, two of China’s largest charities, worked with Africa CDC, Chinese embassies, Ethiopian Airlines, WHO, and United Nations (UN) agencies to distribute 100,000 masks, 20,000 test kits, and 1,000 protective suits to each of the 54 African countries. Each country received 500 ventilators, 200,000 pieces of protective clothing, one million swabs, and 500,000 pairs of gloves in April, and critical re-supplies afterwards.

Chinese government supplies were delivered by its state-owned companies particularly those in shipping, energy, and construction. China Railway Construction Corporation was by far the most prominent. In West Africa alone, 38 tons of Chinese aid was delivered between February and April. By the year’s end African countries received over 400 tons of Chinese assistance. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) delivered COVID-19 aid to around 50 countries and territories, including 21 in Africa between March 2020 and June 2021, accounting for half of all Chinese contributions. About 62 percent went to national militaries and defence ministries. The PLA also held military-to-military exchanges via video conference to share experiences and provide in-country training for military medical units.

While Chinese COVID-19 deliveries were mobilised and dispatched relatively quickly, and massively, China did not necessarily meet African priorities. Leading African epidemiologists noted that African countries needed a public health approach to instil awareness and promote responsible health behaviours while vaccine shortages were being resolved. This required support in two critical areas: culture-based communication at the grassroots level, and scaling up community health workers, none of which China explicitly addressed in its COVID-19 aid policy.

The overriding priorities for Africa were early detection and management, re-building trust with citizens, and preventative health services to ensure that hospitals were not overwhelmed. However, China focused more on supplies, clinical interventions, and vaccine distributions. These are undoubtedly essential, but do not necessarily address the multi sector strategies required to build community resilience and trust.

Vaccines: In May 2020, Xi Jinping pledged to make Chinese vaccines a “global public good.” In October, China joined COVAX, the WHO-backed facility for distributing COVID-19 vaccines. Two Chinese vaccines—SinoPharmand Sinovac—received WHO emergency use authorisation in May and June 2021 respectively. By June, 693 million doses had been delivered to 100 countries, including 40 from Africa. Of these, only about 52 million were donated. The PLA started distributing vaccines in February 2021. By August it had supplied 19 militaries around the world, including 6 in Africa. It also donated 300,000 doses to UN peacekeepers, with priority going to African missions.

However, Chinese vaccine deliveries in Africa have been relatively low, with 56 million doses delivered out of the 86 million doses pledged. Moreover, Africa received the least number of Chinese vaccines in the Global South, behind Asia and Latin America. Secondly, only 9 million of the 56 million doses were donated, reflecting larger global Chinese distribution patterns. To be sure, the AU’s policy on vaccine access focusses on direct purchases and pre-orders, not charity. However, the fact that China sells the vast bulk of its pledged vaccines leaves it open to criticism that it is not delivering a “public good” per se.

Policy Development and Long-Term Capacity Building: The Chinese National Health Commission (CNHC) organises regular video conferences with governments to shape policy priorities and share China’s experience. African countries are also using the CNHC’s “Knowledge Centre on China’s Experiences in Response to COVID-19,” a one-stop-shop for technical guidelines, protocols, and training on China’s response. China has also committed itself to prioritising vaccine access, a major AU policy goal that is likely to be a top agenda at the forthcoming Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit in Dakar, Senegal. Specifically, African countries are hoping to secure a firm commitment from China to support the AU Partnership for Vaccine Manufacturing that seeks to achieve self-sufficiency in vaccine manufacturing by 2035.

One criticism of China’s capacity-building approach is that it appears to prioritise the Chinese experience rather than facilitating the exchange of knowledge, lessons, and expertise between African countries. This could be a much more effective use of Chinese resources given that African countries are confronting different waves of COVID-19 and have used an array of tactics suited to their own conditions. Moreover, there are major differences between the Chinese and African contexts and most African governments do not have the resources to implement the Chinese model in its entirety.

Conclusion

As the triennial FOCAC Summit approaches, China is hoping to see a return of investment for its COVID-19 engagements in terms of soft power, prestige, influence, and goodwill. It is not just banking on its activities amidst the pandemic, but a history and institutional memory of medical and public health engagement going back to Africa’s independence era. Surprisingly, however, this vast knowledge does not appear to have been contextualised beyond the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines, medical supplies, and clinical services. If Chinese assistance is to be aligned more closely with African needs, it will need to be recalibrated to ensure that China learns from African countries as much as they learn from its experience.

Paul Nantulya is Research Associate at the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies.