Dr Joseph Olusegun Adebayo is a National Research Foundation (NRF) Innovation Postdoctoral Fellow in African Studies at the University of Cape Town. His research interests include good governance and democracy in Africa, analyses of media (mis)representation of Africa, analyses of media framing of land reform and democracy in South Africa and the dynamics of African elections.

Abstract

African elections are unique in several respects; in ethno-religiously divided nations, elections are often decided on the basis of candidates’ ethnic or religious affiliations rather than political ideologies. In Nigeria for example, campaigns differ greatly from what is obtainable in other countries. For example, music plays a huge role in the outcome of elections in Nigeria. It also significantly determines whether or not the elections will be violent or non-violent. This is because music evokes emotions and connects with people in a personal and intimate way. This study critically examines the two-edged nature of music’s effect on society and offers some evidence to demonstrate that music can help in fostering peace in the society particularly as it concerns peaceful elections. Adopting an ethnographic research methodology, the article’s argument draws on examples from Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, countries where the medium of music was fittingly utilised to promote peaceful non-violent elections.

Background to study

Music is unquestionably one of the most mysterious and most intangible of all forms of art. It is a powerful medium through which life is expressed. Love and hate, friendship and enmity, joy and sadness, hope and despair etc. can all be expressed through the potent channel of music. Storr (1993:168) avers that music’s influence on society, particularly in its ability to create a sense of communal collectivity, has been greatly underestimated. He opines that music offers a binding power that unifies people from all ages and in diverse corners of the earth, making it one of the most powerful tools for social mobilisation and sensitisation.

In Africa, music plays a vital role in mobilisation, sensitisation, socialisation and cultural transmission. It is a very potent medium through which oral traditions are transferred from one generation to another. When a baby is born in Africa, we sing; when an old man or woman dies, we sing; when the harvest is good, we sing; when the harvest is bad, we sing; when we want to mobilise for war, we sing; when we want to entreat for peace, we sing. There is a song for every occasion in Africa. To the African, music is not just a pastime, it is a ritual; it describes his true essence, a source of his ‘humanness’. Steve Biko aptly describes music in the African context thus:

Nothing dramatises the eagerness of the African to communicate with each other more than their love for song and rhythm. Music in the African culture features in all emotional states. When we go to work, we share the burdens and the pleasure of the work we are doing through music. This particular fact, strangely enough, has filtered through to the present day. Tourists always watch with amazement the synchrony of music and action as Africans working at a roadside used their picks and shovels with well-timed precision to the accompaniment of a background song. Battle songs were a feature of the long march to war in the olden days … in other words, with Africans, music and rhythms were not luxuries, but part and parcel of our way of communication (Biko 1978:41).

This article argues that music’s huge influence has not been fully employed to promote peace and harmonious coexistence between Africa’s diverse people, particularly during election periods. Focusing on the impact music has on Nigeria’s socio-political milieu, the argument is that music can play a huge role in the country’s political transformation. A central point here is that Nigeria’s music has experienced a huge followership over the last few decades, particularly amongst the nation’s teeming youth. Considering that people under the age of 35 constitute about 65% of Nigeria’s population (National Population Commission 2006), it becomes imperative to study the type of music they listen to, the content of such music and the impact it has on their political decisions. Thus, this study includes a focus on the interactions between music and political discourse in Nigeria and provides some empirical observations on how Nigerian tertiary students were affected by music.

Methodology

The researcher adopted ethnography as a research methodology. In order to observe and experience the behaviour of the selected students, the researcher visited and lived on the selected campuses as a participant observer over a period of six months (late 2014 to early 2015). The study population included 200 randomly selected students in tertiary institutions situated around Ilorin Metropolis in Kwara State, North Central Nigeria –the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), the Kwara State University (KWASU), the University of Ilorin (UNILORIN) and the Al-Hikma University. Although the study was not limited to young adults, the majority of respondents were youths who, it was discovered during the study, easily identified with current genres of music.

Participant observation, focus group discussions, and in-depth interviews were used as methods of data collection. Considering the complexity of the issues involved, it became pertinent to get immersed in the field setting for a reasonable time in order to feel the social dynamics that questionnaires and other data collection methods cannot capture. Wolcott (2005:57) is of the opinion that for ethnographic studies to be successful, it requires that a researcher gets personally immersed in the ongoing social activities of some individuals or groups involved in the research.

Describing the Sample

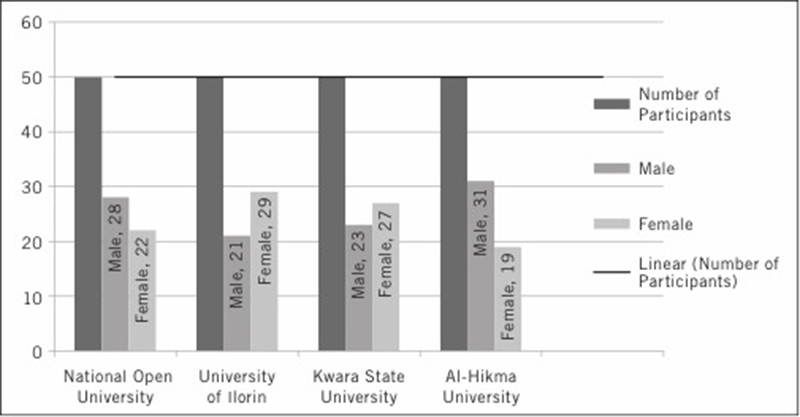

A total of 50 students were interviewed in each of the selected institutions. A total of 28 males and 22 females took part in the study at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN); 29 females and 21 males were sampled at the University of Ilorin; Kwara State University had 27 females and 23 male respondents; while 31 males and 19 female students made up the sample at Al-Hikma University. In total, 103 of the 200 respondents were male, while 97 were females. The gender distribution of the selected participants is presented in figure 1 below.

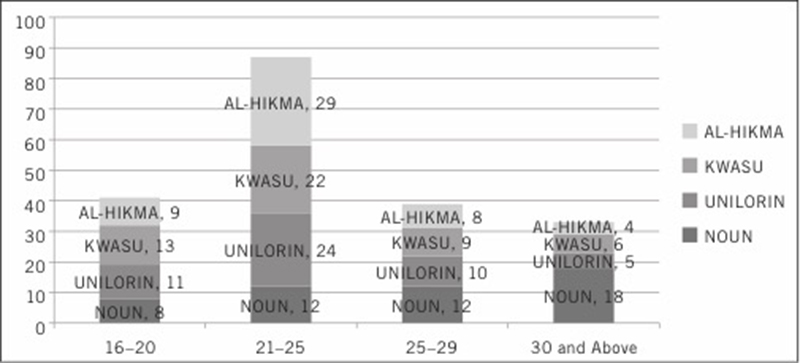

Figure 2 shows the age range of the sampled population – a very young, political active and vibrant age group. A total of 41 students (21%) out of the sampled population belonged to the age bracket 16–20, 86 students (43%) were within the age bracket 21–25, the age bracket 25–29 had 39 respondents (20%), while only 33 respondents (16%) were above the age of 30. The figure also shows that 18 of the 33 respondents above the age of 30 were from the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN). This may not be unconnected with the fact that NOUN caters for older students who mostly combine work and study.

Music in pre-colonial Nigeria

Before 1914, what is today known as Nigeria never existed as a unit. It was a geographical area made up of people of dissimilar cultures and beliefs. The diversity of pre-colonial Nigeria originated in the different origins and cultures of the various ethnic groups, and these differences were also evident in their music. Pre-colonial music in Nigeria differed in style, theme, and lyrics according to the practices in each ethnic group. For example, Yoruba music in pre-colonial Nigeria was not motivated by monetary gains; it was mainly centred on folklore and spiritual deity worship (Atanda 1980:32). The instruments were not ‘sophisticated’ and modern, the musicians utilised basic and natural ‘instruments’ such as whistling and clapping of hands. The talking drum, for example, was a significant musical instrument in pre-colonial Yoruba society, and it is still popular today.

Omojola (2010:33) thus remarks about the changing function of musical instruments in Yoruba culture over time:

The social and religious functions of Yoruba musical instruments often change over time. For example, the igbin drum was originally a secular instrument played to entertain Obatala (believed to be the sky father and creator of human bodies by the Yorubas. According to Yoruba folklore, he was brought to life by Olodumare’s smooth breath) in his lifetime. He loved the sound of the drum so much that he named the different instruments of the ensemble after his wives, namely iya-nla, iya-agan, keke and afere. Iya-nla is the principal drum, while iya-agan, keke and afere are the three supporting drums, known collectively as omele. The use of igbin drums assumed a sacred significance when they were adapted by the devotees of Obatala to accompany sacred rites in honour of their deity. Two drums, bata and dundun, whose roles and functions have also changed in recent times provide interesting perspectives on the ways in which the sacred and the secular have continued to merge in Yoruba music.

Similarly, Igbo music in pre-colonial Nigeria was largely intended for ritual and ceremonial purposes. The Igbos used music to worship their deity, to celebrate festivals, to initiate warfare and as a form of social protest. According to Ojukwu (2008:183), to the Igbo, music was (and still is) very political. The sound of the ogene,1 depending on the tuning and intensity and the time it is played, often would tell whether or not a leader was still relevant or accepted by his/her people.

Hausa music, like that of the Yoruba and Igbo, also had a deep religious and cultural ‘obligation’ to pre-colonial Hausa society. Music in pre-colonial Hausa land was not just a tool for entertainment; music provided an avenue for the transmission of culture, history, and folklore. In traditional Hausa communities, a musical performance was a ceremony and was used as a status symbol. Musicians were generally chosen for political reasons as opposed to musical ones. The Hausa society also had a bank of courtly praise-singers who were hired and given the task of singing the virtues of patrons such as the Emir or Sultan (Ochonu 2008:99).

It is pertinent to state here that although Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa music are highlighted here as representative of music in pre-colonial Nigeria, they do not exhaustively cover the 250 other ethnic groups in the country. But given similarities in the culture of the various ethnic groups in Nigeria, it can be safely said that the selected tribes present a cursory idea of music in pre-colonial Nigeria.

The place of music in the socio-political milieu

A song is something that we communicate to those people who otherwise would not understand where we are coming from. You could give them a long political speech – they would still not understand. But I tell you: when you finish that song, people will be like ‘Damn, I know where you niggas are comin’ from (Sifiso Ntuli, in Vershbow 2010).

Music’s immense influence was evident in the struggle for independence in most African countries. Rallies, protests, and movements were laced with music and dances; musicians released albums that were filled with contents calling for the emancipation of their countries. In South Africa, for example, music was a major pivot for the anti-apartheid struggle. As Schumann (2008:19) asserts, inside South Africa music played a significant role in putting pressure on the apartheid regime. She recounts that artists such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Paul Simon and several others provided South Africans with the songs that were sung by demonstrators as they embarked on their numerous marches across the country against apartheid.

Nigerian musicians also played active roles in the quest for the attainment of the country’s independence. Even after Nigeria attained independence in 1960, musicians were in the forefront of championing calls for social justice and political transformation. According to Adegoju (2009:4), Nigerian musicians have always been in the forefront of advocating for positive social change through their music. He argues that before the recent transformation of the music industry in Nigeria, musicians were considered as social crusaders who led social protests through the medium of music and who communicated the people’s frustrations with the government of the day through their lyrics. Musicians like Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Sony Okosun, Onyeka Onwenu, Christie Essien Igbokwe, Dan Maraya Jos, Femi Kuti, Bisade Ologunde (Lagbaja) have severally used their music to sensitise and mobilise the populace towards social change and to call the government in power to ‘order’ when they erred.

Brown (2008) is of the opinion that almost every sound of music is political. He argues that even when the music is laced with sexually explicit content, it has a political undertone and engaged listeners will pick up the politics. Brown’s views are given credence by the immense socio-political lyrical content of Hip-hop music which has a deep historical root in the expression of social and political protests initiated through music by urban African-American youths. Petchauer (2009:952) also posits that Hip-hop pedagogy has grown in the past ten years, as scholars and educators have researched and experimented with the use of Hip-hop music and culture to improve students’ empowerment, cultural responsiveness, and skills of literary analysis and critical literacy. Music’s potential as a tool for socio-political transformation and as a catalyst for social revolution should not be understated. Plato warned that ‘the modes of music are never disturbed without unsettling of the most fundamental political and social conventions’ (Plato, The Republic, in Byerly 1998:27). Braheny (2007:18) argues that music can be representational, and this, according to him, confirms music’s interrelatedness with politics. Most musicians with a knack for activism often lace their music with clearly defined political viewpoints that represent their views about happenings in society and how people can take charge of their destinies.

Perhaps no Nigerian musician exemplifies the use of representational music more than the late Afrobeat sensation Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, popularly referred to as Fela. An ardent traditionalist, social critic and staunch believer in African traditional religion, Fela believed that the most important things for Africans to fight against were: European imperialism, dictatorship and tyrannical governments on the continent. Fela steadfastly and consistently stood for and fought for the rights of society’s underprivileged and vulnerable. Olaniyan (2004:242) affirms that Fela himself alluded to the representational nature of his music when he stated: ‘I am using my music as a weapon. I play music as a weapon. The music is not coming from me as a subconscious thing. It’s conscious’.

A classic example of Fela’s representational music is the 1977 archetypal lyric entitled ‘No Agreement’:

No agreement today / No agreement tomorrow / I no go gree

Make my brother hungry / Make I no talk / I no go gree

Make my brother homeless / Make I no talk

No agreement now, later, never, never, and never (Olaniyan 2004:168).

Fela, in this song, presented himself as the spokesperson for the poor and downtrodden in the society. He declares that he will not stand mute and watch his people suffer because of government’s irresponsible leadership. Fela’s songs were analogous to whistle blowing as he consistently brought perpetrators of societal ills and injustices to public knowledge and sensitised the public into rising up against corruption, tyranny, and dictatorship that pervaded Nigeria during the heydays of Fela’s musical activism.Olaniyan (2004:167) describes Fela’s musical messages as defiance against the political status quo of his days and in spite of several government clampdowns, arrests, detentions and even threat to life, he remained bold and unrepentant, thus winning over a critical mass of people who still adore him today. His songs addressed an array of social issues such as tyranny, corruption, ethnocentrism, tribalism, religious bigotry and extremism, hypocrisy.

Perhaps a major proof of the generational impact of Fela’s music is the adoption of his songs by social protesters across Nigeria. For example, during the January 2012 fuel subsidy protests that rocked major cities in Nigeria, Fela’s songs were used to motivate and inspire the protesters. Students in Nigeria’s tertiary institutions have adopted several of Fela’s songs and associated most of their lyrics to their demands and demonstrations against perceived deprivations and social injustices.

Music’s effect as two-edged sword

Music’s immense influence can be likened to the impact of two-edged swords with the possibilities to positively or negatively shape and influence the direction of society. History is awash with examples of how music was used as a tool to feed hatred in the hearts of men leading to the preventable deaths of millions of people. In the same vein, history is not short of instances where music’s huge sway positively mobilised and sensitised society towards the attainment of positive societal goals.

The unfortunate genocide that ravaged the beautiful nation of Rwanda in 1994 brings to mind the immense influence music wields in society. During the trials at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda that ensued after the unfortunate genocide, a popular musician, Simon Bikindi was indicted for a crime against humanity. The charges against him, according to the tribunal, included a deliberate conspiracy to initiate the annihilation of a certain segment of society through systematic genocide. He was accused of directly inciting the public to commit genocide by murdering and persecuting members of opposing ethnic group(s).

Gowan (2011:51) holds that Bikindi incited genocide with his music, thereby abusing the huge followership of his music in the Hutu community. Bikindi’s indictment was for composing music that is said to have supported hatred for the Tutsi people, leading to their massacre in 1994. This has inspired much controversy regarding where the line should be drawn between freedom of speech and incitement to gross human rights violations. As Akinfeleye (2003:11) posits: freedom or liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no courts can save it.

The prosecutors in the trial of Bikindi examined two of his songs on the basis of their lyrics and the effects they had on inciting the public towards acts of genocide. According to Gowan (2011:54), the first song examined, ‘Twasezereye ingoma ya cyami’ (We said goodbye to the Feudal regime), was first performed in 1987 at the time of Rwanda’s 25th anniversary of independence. The lyrics verbally assaulted the monarchy which was removed in 1959, and celebrated the end of feudalism and colonisation. This particular song was later recorded in a studio in 1993 as part of an album and focused popular dissent against the peace plan being developed in Arusha, Tanzania at the end of the Rwandan Civil War in 1993. At this point, ‘Twasezereye’, like several of Bikindi’s songs, turned from simple hate speech to a demonstrable element of a consciously deployed call to genocide.

Bikindi’s second song, ‘Njyewe nanga Abahutu’ (I hate these Hutus), also contained illicit lyrics that overtly called on Hutus to systematically eliminate Tutsi minorities. In the opinion of Cloonan (2006:22), the song was not just a song against Tutsis and moderate Hutus; it was a song that was completely anti-coexistence. Bikindi in this song uses lyrics to gain support and inspire a reaction from the listener. He refers to the moderate Hutu as ‘arrogant’, a word that has monarchical undertones and could imply that the moderate Hutus are more like the Tutsi than they are like the Hutu. The lyrics of the song contained overt hatred for Tutsis and moderate Hutus:

I hate these Hutu, these arrogant Hutu, braggarts,

Who scorn other Hutu, dear comrades!

I hate these Hutus, these de-Hutuized Hutu,

Who have disowned their identity, dear comrades!

I hate these Hutu, these Hutu who march blindly, like imbeciles,

This species of naïve Hutu who are manipulated, who tear themselves up,

Joining in a war whose cause they ignore.

I detest these Hutu who is brought to kill – to kill, I swear to you,

And who killed the Hutu, dear comrades.

If I hate them, so much the better … (Gowan 2011:65).

Bikindi refers to the ‘de-Hutuized Hutu’ as specie, implying that they are sub-humans who do not deserve to be treated as equals. De-humanising the enemy has always been a tactic used in war. Bikindi’s lyrics go on to mention ‘Joining in a war whose cause they ignore’, most likely referring to the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front’s invasion of Rwanda in 1990 in order to ‘overthrow[President] Habyarimana and secure their right to return to their homeland’ (Gowan 2011:59).

It is sad to state that the government used the power and influence of Bikindi’s popular, nationalistic folk tunes as a tool to incite hatred between ethnic groups – a hatred that ultimately led to a 100-day massacre of the Tutsi minority, recorded as one of the most gruesome genocides in the history of mankind. According to Gowan (2011:59), a piece of music cannot be judged solely on its content, but as heard within the context in which it was created, especially if the lyricist is still alive and able to control where, when and in what contexts his music is performed. However, it is very clear that Bikindi’s songs were deliberate, intentional and well-orchestrated to illicit hate and to encourage genocide.

The impact of music on (non-)violent elections

It is important to state that although music’s influence on society can be negative, as exemplified by Bikindi’s music discussed above, music has also been found to be a veritable medium through which society can be mobilised and sensitised for worthy causes such as the promotion of peaceful non-violent elections. Hitchcock and Sadie (1986:23) opine that music can play a vital role in arousing action in the public towards a very positive cause. For example, Bob Dylan is reputed to be one of the leading lights in the struggle against racial discrimination in America. His songs were so motivating that it served as an inspiration to civil rights groups by emphasising that the fight against racial discrimination should be a concerted one: no one is excluded because of colour.

African elections have historically been marred by electoral violence, usually resulting from an incumbent who is reluctant to hand over power or from an electorate that is gravely divided along ethno-religious lines. According to Hafner-Burton and others (2014:4), in countries like Nigeria, Kenya, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi and Zimbabwe without a well-developed respect for the rights of their citizens, elections increase political polarisation and potentially increase human rights abuses. However, elections in liberal states ultimately bring about wider political involvement, civic commitment and political accountability, all of which will improve respect for human rights over time.

The recent largely ‘successful’ elections in Ghana and the 2013 general elections in Kenya have been linked to the role played by musicians. In the recently concluded 2016 elections in Ghana, for example, musicians, sensing the possibility of Ghanaians resorting to violence after the declaration of election results, took the responsibility of ensuring a peaceful Ghana away from the hands of politicians by staging peace concerts in every part of the country. With a record of five military coups from 1966 to 1981 and six peaceful changes of government through free and fair elections, Ghanaian voters and politicians went to the polls aware of a reputation to protect as one of West Africa’s most promising and stable democracies. Some notable musicians released singles with lyrics calling Ghanaians to put the country first, ahead of ethnic and party affiliations. One particular group of musicians organised the azonto peace dance competition, similar to that organised in 2012 targeted at Ghanaian youths with the sole aim of sensitising them on the need to act in a peaceful manner and shun violence during the 2012 elections. Although there were setbacks in the election and it would be imprudent to adduce the election’s success to music only, the fact remains that political mobilisation and sensitisation before, during and after the elections played a huge role in its peaceful outcome.

Kenya’s experiences were similar to those of Ghana, since elections in Kenya were marred by violence and wanton destruction of lives and property. In 2007, Kenya erupted into its worst violence since independence following the disputed re-election of President Mwai Kibaki, from the Kikuyu ethnic group. Desiring to forestall a possible recurrence, musicians in Kenya organised for peace in several ways ranging from releasing singles and albums on the need for peaceful elections, to staging peace concerts across the major cities in the country. According to Ramah (2012:2), the umbrella body of all musicians and entertainers in Kenya – the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK) – organised a series of concerts and campaigns targeted at ensuring that Kenyans imbibed the culture of non-violence. One of such campaigns was the ‘Ni Sisi Peace Campaign’ to educate Kenyans on the voting process and promote patriotism and unity in the run-up to the March 2013 elections. Thus, Nyoike-Mugo (2010:33) opines that while music played a huge role in the ensuing conflict after the election of 2008, this time musicians took concrete and deliberate steps before the election to ensure that they fostered peace through their songs.

The late musical sage, Christie Essien Igbokwe, known as Nigeria’s lady of songs, was one of the leading voices in the calls for peaceful polls in Nigeria. In one of her songs released in the early 1990s, entitled ‘Moloro yi so‘ (I have something to say), Christy Essien chronicled the history of electoral violence in Nigeria and the wanton loss of lives and properties that characterised such elections. The lyrics of the songs contained overt pleas calling on Nigerians to shun violent acts during elections and to repel politicians with a track record of violence. The song, released at the peak of the regime of General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, got immense airplay on radio and television stations across the country and helped to assuage Nigerians and encourage the need to act peaceably during elections. It can be argued that her songs, coupled with those of other artists, played a huge role in the peaceful nature of the 12 June 1993 general elections in Nigeria, although it was later annulled by General Babangida.

Another musician who has played a significant role in mobilising and sensitising Nigerians on the need to live peaceably with one another is the dexterous Onyeka Onwenu. It may be argued that Onyeka’s background in journalism could have greatly influenced her lyrical prowess. Understanding the immense influence the media wields in setting an agenda for public discourse and shaping public opinion, she exploited the reach, spread and acceptance her music enjoyed amongst Nigerians to preach the need for peace and harmony in the country. One of her most popular songs, ‘One love’, is a classic example of how much she desired peace and unity in the country. The song gained widespread acceptance and was almost a national anthem when it was released in the early 1980s. Onyeka afterward, in the early 1990s, released a single entitled ‘Peace song’, that was also aimed at sensitising Nigerians on the need for peace. Several other Nigerian musicians have overtly preached peace in their songs. Artists like King Sunny Ade, Ebenezer Obey, Lagbaja and Dan Maraya Jos have songs dedicated to calls for peace and harmony in Nigeria and, in particular, peaceful elections.

Vote not Fight: The role of music in Nigeria’s 2015 elections

Elections in Nigeria have been characterised by violence that has led to the loss of countless lives and properties. The build-up to elections in Nigeria is always characterised by voter apathy often linked to apprehensions of violence during elections. Fischer (2002:11) is of the opinion that Nigerian elections are typified by violence, which is either random or organised with the sole aim of delaying or determining the outcome of the election. Electoral violence in Nigeria is often aimed at influencing the outcome of the electoral process through verbal intimidation, hate speech, blackmail, assassination and wanton destruction of properties.

As the date for the 2015 general elections in Nigeria drew near, there was a palpable fear amongst the populace of a possible repeat of the violence that marred the 2011 elections. Human Rights Watch (2011:16) claimed that although the 2011 elections were largely regarded as peaceful by the international observers, it was blemished by the wanton loss of lives and property. Shortly after election results started trickling in at the collation centres, supporters of the rival parties took to the streets and started what would turn out to be one of the most brazen demonstrations of electoral violence witnessed in Nigeria since the First Republic of the 1950s and early 1960s. After the carnage, Human Rights Watch stated that over 800 Nigerians, mostly women and children, lost their lives to the conflict, especially in Northern parts of the country.

Thus, in a bid to prevent a recurrence of the unfortunate incidence of 2011, Nigerian musicians decided to take concrete and deliberate steps towards ensuring that elections were devoid of rancour. There are several reasons why Nigerian music and musicians can play significant roles in stemming the incessant electoral violence. Firstly, Nigerian music is arguably one of the fastest growing industries on the African continent. Nigerian musicians have a huge followership among Nigerians, particularly among her teeming youth population. This huge influence provides musicians the opportunity for what Akpabot (2008:79) refers to as social control.

The social control theory, propounded by Hirschi (1969:2), attempts to explain delinquent behaviours and the factors that limit and/or eliminate them. Hirschi’s aim was to show what prevents juveniles from acting in delinquent ways. He viewed delinquency or deviance as being taken for granted and considered conformity or conventional conduct as being problematic. In the context of music and elections, Akpabot argues that messages in music, if designed to achieve a particular aim (such as non-violent elections), can create a sense of community that discourages and makes violence during the electoral process unattractive, thereby promoting peaceful and non-violent elections.

A prominent musician who took the onus upon himself to advocate for peace during the 2015 elections in Nigeria was Mr Innocent Idibia (popularly known as 2face). His involvement in the election, as well as his role in sensitising the public, forms the main unit of analysis on the impact of music on electoral peace for this study. At the onset of the study, there was no intention of studying 2face’s music and how it impacted on the elections. The plan was to undertake a content analysis of selected songs and find out about the public perception of the impact the songs had on the public’s behaviour before, during and after the election. However, when it became obvious that very few songs advocating peaceful elections gained enough airplay to be analysed, the focus was narrowed down to 2face’s song, ‘Vote not Fight’, which became the major public sensitiser towards non-violent elections.

2face is immensely popular within and outside the shores of Nigeria. Arguably one of the most decorated and most successful African artists of his generation, he has received numerous awards within and outside the continent such as the Music Television (MTV) Europe Music Award, World Music Award (WMA), Music of Black Origin (MOBO) Award, KORA African Music Award, the Black Entertain (BET) Award and the Channel O Award, to mention a few. He is very popular amongst the youth and pulls crowds running into hundreds of thousands to his shows. When this article was being completed (January 2017), he was gradually building a critical mass of people who would protest against the inefficiencies of the current government in Nigeria. Thus, the researcher sought to find out from the student population in his sample the impact 2face’s peace songs had on the outcome of the election in their communities.

Findings

It is no doubt that musicians played a commendable role in the ‘successes’ of the general elections in Ghana and Kenya. Though it is a fact that the success of the elections cannot be totally attributed to the role played by music and/or musicians, it is, however, pertinent to state that they played more than just paltry roles.

In the lead-up to the elections, 2face under the aegis of 2face Foundation started a campaign aimed at dissuading youths from being used as tools for mischief by the political class during elections. The goal of the campaign was to ‘transform the Nigerian youth into peacemakers and ambassadors in their communities for the promotion of a conflict-free environment’ (2face and Youngstars Foundation 2017). As part of the campaign, 2face released a single, ‘Vote not Fight’ in which he urged politicians to desist from provoking young people to commit acts of violence or political hooliganism before, during and after the elections. The song’s first verse and chorus will be content analysed and its impact on interviewed participants discussed.

Verse 1

Cos When Two Elephant Fight

Na the Grass dey Suffer

Grass Go dey Suffer, Grass Go Dey Suffer O

Innocent People Go Dey Run the Cover

The Cover, Each Other

North and South Go Dey Turn on Each Other

Each Other

Instead, Make We Fight Ourselves

Make We Fight Ebola Eh

Instead Of Fighting Corruption Make e No Dey

Some People Na to Do Make Naija No Dey

They Running and Running and They Running Everywhere

So We See Some Disco in the Air

No Matter Wetin Happen Dema Just Don’t Care

Most of Them No Dey Really Live For Here

Dem Don Comeback Again This Year

We No Fear

Chorus

I hear them saying it is a do or die affair

Do or die affair

We don’t want anybody to come scatter ground for here

Scatter ground for here

Vote not fight, that’s what we wanting this year

In this election time (2face and Youngstars Foundation 2017)

In this song, largely sung in Pidgin English, 2face remarks that it is society’s defenceless and vulnerable who suffer in a crisis – and not the political class. He called on Nigerians to collectively focus on the problems plaguing the country rather than fight one another. He remarked: ‘… instead make we fight ourselves, make we fight ebola eh’ (Instead of us to fight ourselves, we should fight ebola). Expectedly, the song gained massive airplay at radio stations in every nook and cranny of Nigeria because of the positive messages therein. In Ilorin where the study was conducted, it was aired several times a day on both the private and public radio stations of the state, with interpretations provided in the local Yoruba dialect.

The first thing the researcher sought to determine was whether or not the sampled population was aware of the song. 183 out of the interviewed sample of 200 averred that they were aware of the song; the majority of them said they got to know the song because they followed 2face on social media and were pre-informed of the song’s release before it became very popular. Most of the interviewed population also averred that 2face was a role model to them; they affirmed that although he has been through some personal scandals and controversies, he still qualified to be regarded as a role model because he had overcome personal adversity. He represented the strength and tenacity with which Nigerian youths overcome harsh conditions.

The sampled population was also asked whether or not they felt 2face was ‘qualified’ to mobilise them for a worthy social cause given his scandalous relationship with multiple women. All the students remarked that they would still follow 2face regardless of the scandals following him; many of them arguing that most of the so-called social crusaders had skeletons in their own cupboards. But that did not deter them from leading their countries’ quest for socio-political emancipation. One of the interviewed students had this to say when asked about 2face’s suitability as a social crusader:

Abeg, na who holy pass? (Please who is without sin?). 2face has always stood for the defenceless in society and most of his songs are laced with lyrics eschewing corruption and calling on Nigerians to do the right thing for the society to move forward. I would gladly come out if 2face ever asks us to join him for a worthy cause. I don’t care how many women he has allegedly impregnated, the fact is that none of them came out to say they were raped.

The above response was echoed during the focus group discussion when the researcher sought to know whether or not the group thought 2face had the moral capabilities to call for positive social change given his history with women. Every member of the group said it would be wrong to judge a man’s ability to lead by his past mistakes. One respondent remarked thus:

The fact is that most of the men who had led us have no good moral standing; they just had a passion for solving problems. I have followed 2face for close to two decades and there is no album of his that does not highlight socio-political issues in the country. He is not attention seeking; he is truly concerned the plights of ordinary citizens.

The researcher then sought to find out whether or not they believed 2face’s song ‘Vote not Fight’ affected their behaviour during the elections. Such findings might be more significant because the students in this study were attending higher institutions of the state itself, and are often the targets of political crackdowns. Despite the dangers, the Students’ Union Governments of two of the sampled institutions adopted the song as their official campaign song against electoral violence.

All the students interviewed, observed and those who took part in the focus group discussions all affirmed that the music played a huge role in making them choose non-violent participation in the political process. Most of the sampled students said the song, amongst other ones, kept ringing in their heads as they were approached by political groups to scuttle the election. Some said even when they went home for the holidays, the song was still being heard as it gained widespread airplay and was even translated into Yoruba. One of the sampled students pointed to a particular section of the song’s first verse. He sang the part as he was being interviewed:

No matter wetin happen, dema just don’t care; most of them (politicians) no dey really live for here, dem don come back again this year, we no dey fear.

The students then collectively remarked, during a focus group discussion, that most of the time politicians use unsuspecting youths as political thugs while their children school and live abroad safely. They also affirmed that when violence erupts during elections, the politicians often fly out of the country as they do not really live full-time in the country. One student said:

When they make us steal ballot boxes and burn tires, they give us 2000 Naira and leave us to our fate. When the community burns, they take the next available flight to Europe or America and then leave those of us that cannot easily run to face the music. What happens to my aged mother and father? What about my siblings? I cannot collect money and then jeopardise the future of myself and family. Although I knew of the dangers of being a tool in the hands of politicians, 2face’s song further reinforced it and made me realise that I actually did have a choice.

However, we observed that not all the students agreed that the song affected their political behaviour. Some averred that they had been sensitised in church and by their parents and that their minds were already made up. They said although 2face’s song reinforced their stance for non-violence, it did not initiate it. There was general consensus however that the song had a far-reaching effect on how young people behaved during the election and that it played a huge role in ensuring that the elections were largely peaceful.

Conclusion and recommendations

It would be imprudent to claim that music was the decisive reason for the peaceful 2015 elections; but our study does indicate that music played a huge role. Artists are not, and cannot be, politically neutral; their art requires them to speak to and for society lyrically and in ways that can sensitise and mobilise people towards the achievement of positive and worthwhile goals. Electoral commissions in most African countries miss the great opportunity that music affords as a tool for mass mobilisation and sensitisation. As part of efforts aimed at reducing or completely eliminating electoral violence across the continent, we strongly recommend that musicians should take part in teams of peace builders. Music communicates to people in ways that go beyond rational argumentation. It touches their souls, and greatly impacts on their lives. When properly utilised, music can help create an opportunity for society to value and apply non-violent alternatives to solving conflict situations.

Sources

- Adegoju, Adeyemi 2009. The musician as an activist: An example of Nigeria’s Lagbaja. Itupale Online Journal of African Studies, 1 (2), pp. 1–23.

- Akinfeleye, Ralph 2003. Fourth estate of the realm or fourth estate of the wreck: The imperative of social responsibility of the press. Inaugural lecture delivered on 14 May 2003 in the Main Auditorium, University of Lagos.

- Akpabot, Samuel 1986. Foundation of Nigerian traditional music. Ibadan, Spectrum Books Limited.

- Ames, David 1973. Igbo and Hausa musicians: A comparative examination. Ethnomusicology, 17 (2), pp. 250–278.

- Atanda, Joseph 1980. An introduction to Yoruba history. Ibadan, Ibadan University Press.

- Biko, Steve 1978. Some African cultural concepts. In: Stubbs, A. ed. I write what I like. Oxford, Heinemann Educational Publishers. pp. 40–47.

- Braheny, John 2006. The craft and business of song writing. Cincinnati, Writer’s Digest Books.

- Brown, Courtney 2008. Politics in Music: Music and political transformation from Beethoven to hip-hop. Atlanta, Farsight Press.

- Byerly, Ingrid Bianca 1998. Mirror, mediator, and prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa. In: Ethnomusicology, 42 (1), pp. 1–44.

- Cloonan, Martin 2006. Popular music censorship in Africa. Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Fischer, Jeff 2002. Electoral conflict and violence. Washington, D.C., International Foundation for Electoral Systems.

- Gilbert, Shirli 2007. Singing against apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle. Journal of Southern African Studies, 33 (2), pp. 422–441.

- Gowan, Jennifer 2011. Fanning the flames: A musician’s role in the Rwandan Genocide. Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology, 4 (2), pp. 49–66.

- Hafner-Burton, Emily, Susan Hyde and Ryan Jablonski 2014. When do governments resort to election violence? British Journal of Political Science, 44 (1), pp. 149–179. Available from: <http://ilar.ucsd.edu/assets/001/pdf> [Accessed 25 February 2017].

- Hirschi, Travis 1969. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Hitchcock, Wiley and Stanley Sadie 1986. New Grove dictionary of American music. London, Macmillan.

- Human Rights Watch 2011. Nigeria: Post-election violence killed 800. Published 17 May 2011.

- National Population Commission (NPC) 2006. Population and housing census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. National and state population and housing tables. Priority Tables Volume I. Abuja.

- Nyoike-Mugo, Wanjiku 2010. The power of song: An analysis on the power of music festivals or concerts as a tool for human rights education in Africa. M.A. thesis, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo.

- Ochonu, Moses 2008. Colonialism within colonialism: The Hausa-Caliphate imaginary and the British colonial administration of the Nigerian middle belt. African Studies Quarterly, 2 (3), pp. 95–127.

- Ojukwu, Chris 2008. Igbo nation, modern statecraft and the geopolitics of national survival in a multiethnic Nigeria. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 3 (5), pp. 182–190.

- Olaniyan, Tejumola 2004. Arrest the music! Fela and his rebel art and politics. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Omojola, Bode 2010. Rhythms of the gods: Music and spirituality in Yoruba culture. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 3 (5), pp. 29–50.

- Petchauer, Emery 2009. Framing and reviewing Hip-Hop educational research. Educational Research, 79 (2), pp. 946–978.

- Ramah, Rajab 2012. ‘Kenya to clamp down hate speech as elections near’. Sabahi Online, 25, pp. 1–8. Available from: <http://sabahionline.com/en_GB/articles/hoa/articles/features/2012/10/25/feature-01> [Accessed 19 February 2017].

- Schumann, Anne 2008. The beat that beat Apartheid: The role of music in the resistance against Apartheid in South Africa. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien, 8 (14/2008), pp. 17–39.

- Storr, Anthony 1993. Music and the mind. New York, Ballantine Books.

- Vershbow, Michaela 2010. The sounds of resistance: The role of music in South Africa’s Anti-Apartheid Movement. Inquiries Journal, 2 (6), pp. 1–12.

- Wolcott, Harry 2005. The Art of Fieldwork. Lanham, MD, Altamira Press.

- 2face and Youngstars Foundation 2017. Vote not Fight, Election no be War. Available from: <http://www.votenotfight.org/> [Accessed 23 February 2017].

Endnotes

- The Ogene is a metal gong used as a ‘master instrument’ by Igbos to pass across information, enhance celebrations and warn communities of possible danger(s).