Abstract

The oil and gas industry is regarded as one of the most dynamic, complex and controversial industrial sectors and involves activities that generate a whole range of diverse viewpoints. This has resulted because the industry has several stakeholders who can influence and, at the same time, be impacted upon by activities associated with the value chain of oil and gas oriented business. However, one extremely important stakeholder is the community. Many researchers (Orsini 2016; Wall 2012; Mascarenhas 2011; Kinslow 2014; Boladeras, Wild and Murphy 2016) agree that the viewpoints of communities where oil and gas operations are carried out should be given high priority due to their significant influence over industry activities in their region, as well as the fact that they are the entities most impacted by these activities. This research examined notable conflicts experienced between oil companies and host communities in Africa with the aim to identify means by which relationships between the two aforementioned parties could be made cordial and sustainable. An integrated literature based research method and a case study strategy were adopted for this research. Two frameworks that will support organisations in effectively engaging and establishing cordial relationships with stakeholders were developed by the author; and the key findings of this research are that an effective means of establishing sustainable cordial relationships with host communities in Africa is by involving them in the ownership of operations in their region. This will naturally instill in them some sense of responsibility over the operations, which will in turn enable oil and gas companies to gain the trust, cooperation and support of host communities, as well as the social license to operate in their region. This relationship can be sustained if both parties work collaboratively to determine ways in which benefits from the operations may be maximised.

1. Introduction

The oil and gas industry is regarded as a very dynamic industrial sector and involves numerous activities that may be viewed from several perspectives. These could include social, political, legal, environmental, technological, economic and commercial viewpoints. These reflect an industry which has several stakeholders and their interests can also be viewed through the aforementioned perspectives. A stakeholder is an individual, group or organisation with interests in a venture and can influence or be influenced by activities associated with the venture (Dooms 2019:64, Freeman 2010:53). In other words, we can refer to a stakeholder as an individual or group with potentials for enabling one to achieve the objectives regarding a particular venture and can also jeopardise the prospects for achieving objectives as well.

Effective management of stakeholders involved in the value chain of oil and gas businesses is vital for the success and sustenance of the industry from both short and long-term perspectives. The Association for Project Managers (2019) defined Stakeholder Management as ‘the systematic identification, analysis, planning and implementation of actions designed to engage with stakeholders’. Stakeholder Management could also be regarded as a set of techniques that aim at harnessing the positive influences (which may include sustained interest, involvement, goodwill and support) of stakeholders while minimising the effect of their negative influences (which may include disinterest, disruption, sabotage and delays) towards actualising the benefits of a given venture (Hinrich 2014; Nikolay and Aime 2004; Lehtinen, Aaltonen and Rajala 2019; Jim and Peter 2004; Reeman 2012). From the aforementioned definition, we can deduce that the main goal of stakeholder management is to establish cordial relationships among stakeholders of a given venture through effective and careful management of their expectations and objectives while attempting to achieve one’s own. As with other management aspects, stakeholder management will involve planning and formulation of effective strategy by utilising data gathered in the analysis of a given situation, then the careful implementation of the strategy developed.

Lester (2007:27); Fritz, Rauler Baumgartner and Dentche (2018:65); Chanya, Prachaak and Ngang (2013:481) agree that the type and interest of stakeholders are of immense importance to organisations, as these can be utilised to enhance performance from corporate, business and operational perspectives. The aforementioned researchers regard Stakeholder Identification and Categorisation as the most significant step in Stakeholder Management and support the classification of stakeholders into two distinct categories, which include Direct (Primary) Stakeholders and Indirect (Secondary) Stakeholders. Direct stakeholders are entities that play a visible role in a particular venture and are impacted by it, while indirect stakeholders are those not involved in the venture but interested in it and inclined to monitor its progress (Lester 2007; Fritz, Rauler Baumgartner and Dentche 2018; Chanya, Prachaak and Ngang 2014).

In the context of an oil and gas operation, the direct stakeholders will include the oil and gas company, host community, government (both local and national), financial institution, investors and regulatory authorities (Wall 2012; Ahmed 2019, Fritz, Rauler Baumgartner and Dentche 2018; Genter 2019; Orsini 2016; Linnen 2016; Boladeras, Wild and Murphy 2016). The indirect stakeholders will then include NGOs, academia, media and foreign governments (Wall 2012; Ahmed 2019, Fritz, Rauler Baumgartner and Dentche 2018; Genter 2019; Orsini 2016; Linnen 2016; Boladeras, Wild and Murphy 2016).

As mentioned in the definition of stakeholders presented earlier in this report, each of the aforementioned stakeholders have their respective influence on the success of an oil and gas operation. However, many researchers (Orsini 2016; Wall 2012; Mascarenhas 2011; Kinslow 2014; Boladeras, Wild and Murphy 2016; Mumma-Martinon 2014) agree that host communities of oil and gas operations are stakeholders of significant influence, as their reaction to industry activities in their region can heavily impact on the value chain of oil and gas businesses.

Recognising the critical importance of the community as stakeholder, the main objective of this research is to examine the community engagement policies and strategies of notable oil and gas companies operating in key oil producing countries in Africa and identify measures and frameworks for improvement. The questions this research seeks to answer are: how has the oil and gas industry fared in engaging with host communities in Africa and how can the relationship between both parties be improved and sustained?

The Integrative Literature Based Research Methodology was combined with the Case Study Research Strategy in order to assess how the oil and gas industry has fared in its dealings with host communities in Africa, as well as identify dilemmas that have emanated in the process.

Findings from this research will support oil and gas companies in formulating effective policies and strategies that will enable them to establish and sustain cordial relationships with communities in Africa where operations associated with the value chain of their businesses are based. The Academy will also benefit from the concepts introduced in this report which could be further explored in subject areas associated with social science, business strategy and policy studies in the African context of language as a symbol of power and resource, and an instrument that can exacerbate conflict when there is a symbolic emphasis on one language in communication and writing over others; when language is used as an instrument to undermine the social and economic advancement of another group; and when used to consolidate economic and political power.

2. Theoretical framework

Several researchers (Leonidou, Christofi, Vrontis and Thrassou 2018; Pollak, Bow and Hanson 2017; Webler, Tuler and Krueger 2001) have established that a significant component of value creation in business is the development and management of sustainable cordial relationships with a variety of stakeholders. Leonidou, Christofi, Vrontis and Thrassou (2018:245) further recognise stakeholder management as a task of growing significance and constituent for a win-win outcome for the parties involved. The conventional procedure for managing stakeholders involves a series of interdependent activities, each of which must be effectively carried out in order to achieve favourable results. These activities include identification of stakeholders; analysis of stakeholders; prioritisation of stakeholders; formulation of stakeholder engagement strategy and implementation of the stakeholder engagement strategy (Shah and Bhaska 2008; Shropshire and Hillman 2007). In the course of embarking on the aforementioned activities, there are important factors that must be considered which could significantly impact on the stakeholder management process. These factors include organisational/reporting structure, communication, consultation, risk, ability to negotiate and compromise (Hinrich 2014, Jim and Peter 2004; Nikolay and Aime 2004). Lehtinen, Aaltonen and Rajala (2019:62) recommend the establishment of decision-making boundaries and transparency as means of achieving continuous dialogue between stakeholders and avoiding possible conflicts. Reeman (2012) supports this by highlighting the need to factor into consideration the inequality of perception on aspects of concern between parties involved. Rempel, Holmes and Zana (1985:97), in their report, emphasised the importance of ‘trust’ in establishing a sustainable, cordial relationship with stakeholders. Trust is recognised by other researchers (De Oliveira and Rabechini 2019; Mayer Davis and Schoorman 1995) as an intrinsic motivation for partnership between two or more parties. Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995:710) demonstrate the importance of trust in developing cordial relationships, and illustrate that one of the parties in the relationship accepts vulnerability to the actions of the other party – basing this on the expectation that the party carrying out the action will monitor and control its impact. Aubert and Kelsey (2000:10) share similar viewpoints, but argue that understanding interdependencies between parties involved in a given venture is a good foundation on which cordial relationships can be built. In line with the opinions of these authors, we could infer that engaging with stakeholders is an intensive process that entails critical analysis of the situation and planning at the preliminary stage in order to establish mutual understanding, trust and cordiality between the parties involved. In addition, an effective stakeholder engagement process must be legal and fair; it should also be transparent in areas of concern and reflect the rights of the parties involved as emphasised by Lehtinen, et. al (2019) and Webler, Tuler and Krueger (2001).

Several of the conflicts experienced in the oil and gas industry have inadequate involvement and management of stakeholders as one of the major root causes (Orsini 2016; Reeman 2012; Mascarenhas 2011). In terms of involving stakeholders, Eberhard and Olsen (2014) recognise that the industry has not fared well in effectively identifying and communicating with stakeholders, resulting in several conflicts, past and present. These highlight the need for Stakeholder theory, which stresses the need for organisations to adopt appropriate business ethics in their processes and effectively communicate with stakeholders while addressing areas of concern in order to achieve both short and long-term objectives (Freeman 2014; Henry 2011). Dunham (2012); Pollard and Bennun (2016) identified some benefits of stakeholder management with respect to the oil and gas industry. These include: collection of traditional knowledge which could be used to shape progress and development; opportunity to address regulatory issues from relevant perspectives; formulation of effective plans that will integrate participation of stakeholders towards project success; collection of data that will be used in balancing the benefits of a project with its costs; enhanced transparency with improvement of reputation; and social license to operate. Though it is evident that effectively managing stakeholders will bring the industry significant benefits, the concern is to what extent is this being achieved in the oil and gas industry? According to Reeman (2012), there is a growing practice in the industry that involves engagement with relevant stakeholders using stakeholder engagement tools, with emphasis on the process of greater consultation towards implementation of strategies derived from feasibility studies and impact assessments. But taking note of aggrieved stakeholders and the conflicts experienced in the industry, one would question the industry’s approach to engaging with its stakeholders – depriving the industry from achieving the full benefits of establishing cordial relationships with stakeholders of significant influence.

Wall (2012) emphasised that oil producing communities should be regarded as stakeholders with very great influence in the oil and gas industry. They are the most severely impacted by industry operations (from socioeconomic and environmental perspectives) – and are capable of causing significant disruptions to operations in their region. However, if host communities give consent and social license to operate, the industry operations can achieve huge levels of success. Orsini (2016); Kinslow (2014); Boladeras, Wild and Murphy (2016); are all in support of this view. Reeman (2012) highlighted that one of the main concerns regarding how the industry has fared in managing its stakeholders, is its dealing with oil producing communities on the societal impact of its operations. This is also consistent with Mascarenhas’ (2011) observation, that most oil and gas operations experience oppositions from communities during application stages or after the operations have commenced. Parshall (2014) highlights key concerns which indigenes of oil producing communities have regarding industry operations in their region. They include environmental issues of water use; contamination of ground water aquifers; waste disposal; emissions; traffic of heavy moving vehicles and noise. There is glaring evidence that in several cases the industry has not performed well in engaging with oil producing communities, resulting in these communities experiencing the resource curse phenomenon. These concerns have been raised by the European Parliament (2011) in their report which blames oil and gas companies for conflict and social unrest experienced in the African communities where they operate.

2.1 Cases of Conflicts between Host Communities and Oil Companies in Africa

The following table provides a summary of notable conflicts between oil companies and host communities in Africa, as well as the underlying causes of the conflicts.

Table 1: Cases of conflict between communities and oil companies operating in Africa.

| Country | Community | Oil and Gas Company operating within the region | Cause of conflict |

| Nigeria | Bodo and Ogoni | Shell | Environmental degradation caused by spillage from oil installations in the region |

| Angola | Cabinda | Chevron | Environmental impact caused by oil spillage and perceived unfairness in terms of allocation of revenues |

| Chad | Doba | ExxonMobil | Environmental and Health impacts of oil and gas operations in the region |

| Sudan | Dinka and Nuer | GNPOC | Politically induced displacement of communities to allow for oil and gas exploration and production |

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | Muanda and Communities bordering Virunga | Perenco, Soco International PLC | Environmental and Socioeconomic impacts of oil and gas operations in the region |

| Algeria | Ain Salah | Consortium made up of Sonatrach, Total and Halliburton | Environmental and Socioeconomic impacts of oil and gas operations in the region |

| Ghana | Keta | Swiss African Oil Company | Environmental and Socioeconomic impacts of oil and gas operations in the region |

| Gabon | Obangue | Addax | Environmental degradation caused by poor waste management practice |

As it has been established that host communities are amongst the highly influential and most impacted stakeholders in the value chain of oil and gas oriented operations, it would be right to emphasise that the effectiveness of an oil company in engaging with host communities will determine the success of the company’s operations in that region. The community engagement strategies of some notable Multinational Oil Companies are reviewed in the next paragraph.

Shell’s approach to community engagement involves identifying concerns of host communities, which inform their planned activities in the region; as well as implementing corporate social responsibility programmes, which include providing scholarship to indigenous students; supporting sports programmes organised by indigenous communities; providing health facilities and employment (Shell 2018). Several oil and gas companies including Chevron, ExxonMobil, Perenco, Addax and Soco International Plc also share a similar approach in implementing corporate social responsibility programmes in regions where they operate (Chevron 2018, ExxonMobil 2018, Perenco 2018, Addax 2018, Soco International Plc 2018). Kabir and Thai (2021) and Singh and Misra (2021) agree on the notion that the Stakeholder Theory inculcates corporate social responsibility initiatives as an organisation’s commitment to its respective stakeholders, and also, obtains legitimacy from the concerned stakeholders. Kabir and Thai (2021) further expatiated on this view by stating that conflict of interest between an organisation and a stakeholder should determine the corporate social responsibility undertaking of the organisation with the stakeholder in concern. This is also in line with the conventional stakeholder management procedure which necessitates the identification of stakeholders as well as their concerns, and work towards establishment of mutual grounds, which will enable the organisation gain their support in achieving set objectives. But the recent conflict between Shell’s subsidiary in Nigeria (Shell Petroleum Development Company) and the Bodo community in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria has presented evidence regarding the inefficiency of Shell’s approach in engaging with host communities. According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2017), Shell’s conflict with the Bodo community in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria started as a result of two oil spills which occurred in the region in year 2008 and 2009. This resulted in the Bodo community filing a lawsuit against Shell at the London High Court on the 23rd of March 2012 which lasted for three years (Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2017; Vidal 2015). The circumstances that led to the conflict between Shell and the Bodo community are in line with Reeman’s argument that the main concern regarding how the oil and gas industry has fared, is its dealing with oil producing communities regarding its operations (Reeman 2012). It was reported that the reason for the oil spills in the region were as a result of poor maintenance of Shell’s oil pipelines in the region. Shell was alerted of this by the community, but reacted slowly to the concern (Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2017). Shell was found liable by the London High Court for the oil spills in the region and agreed to pay $55 million in compensation to the Bodo community as well as clean up the oil spill (Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2017; Vidal 2015). Another concern regarding Shell’s community engagement policy and their relationship management with communities is the extent to which they learn from previous events, as the Bodo case is just a recent development. Long before the issue between Shell and the Bodo community, Shell had a serious conflict with the Ogoni community in the same Niger Delta region of Nigeria during the 1990s (BBC 2017; Olawoyin 2017; Aljazeera 2016; Pilkington 2009). The Ogoni community suffered a high degree of environmental degradation caused by Shell’s operations in the region (BBC 2017; Aljazeera 2016). As a result of the numerous oil spills the region has experienced due to Shell’s operations, a group known as MOSOP (Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People) led by the late Ken Saro Wiwa was established to act as a human rights group for the Ogoni indigenes against Shell and the Nigerian government (Olawoyin 2017; BBC 2017; Aljazeera 2016; Pilkington 2009). It is believed Shell provided support to the Nigerian Military which led to the arrest and execution of the group’s leader and eight of his accomplices (Olawoyin 2017; BBC 2017; Pilkington 2009.). The execution of the MOSOP leaders sparked an international outcry, which eventually resulted to Shell being ordered to cease its operations in the Ogoni region, with several environmental and human right lawsuits filed against Shell by the indigenes of Ogoni ever since the 1990s till date (Olawoyin 2017; Amnesty International 2017; Waronwant 2015; BBC 2017).

The case between Chevron and the indigenes of the Cabinda region of Angola has similarities with that of Shell and the communities in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. According to Redvers (2012), Chevron via its subsidiary in Angola (Cabinda Gulf Oil Company) has been operating in the Cabinda region of Angola since the 1970s. There are concerns regarding how Chevron have engaged with and managed their relationship with the communities in the Cabinda region where a majority of the indigenes make their livelihood from fishing (Redvers 2012; European Parliament 2011). The indigenes have expressed concerns that their fishing profession has been heavily impacted due to oil spillage from Chevron’s installations in the region and they are not appropriately compensated for this (Redvers 2012; European Parliament 2011). They have also further expressed that inasmuch as the resource extracted from their region contributes significantly to Angola’s commodity exports, they have not fairly benefited from this and the region is regarded as one of the poorest provinces in Angola (Redvers 2012; European Parliament 2011). The European Parliament (2011) in their report, stated that indigenes of oil producing regions in Angola are discontented and feel neglected by the oil companies operating in their region and the Government. As a result of these, there have been series of agitations by the indigenes of the Cabinda region which resulted in some kidnapping incidents of Chevron’s employees (Redvers 2012).

There is a similar situation in ExxonMobil’s activities in the Doba region of Chad as highlighted by the European Parliament (2011), where indigenes of the region have voiced their plight resulting from the socioeconomic, environmental and health impacts of ExxonMobil’s operation in the region.

A similar situation is also noted in the Dinka and Nuer region in Southern Sudan, where thousands of indigenes from these tribes were forcefully displaced from their area by the government in order to allow for oil and gas operations by the Greater Nile Operating Company (GNOPC) (Human Rights Watch 2003).

In Algeria, the case between the Ain Saleh community and the consortium comprising of Sonatrach, Total and Halliburton is also identified. The Ain Salah community reside in the southern part of Algeria, they depend on agriculture as their means of livelihood (Cooke 2017; Simon and Weber 2017). Their conflict with the Angola’s state oil company Sonatrach and its partners which erupted in 2015 was as a result of concerns regarding water pollution by the shale oil and gas exploratory projects carried out in their region (Cooke 2017; Watanabe 2017; Simon and Weber 2017; Daragahi 2015). The community source almost all their water from aquifer systems and there are fears that the underground water deposits they depend on would be contaminated by the exploratory projects being carried out in the area (Cooke 2017; Watanabe 2017; Simon and Weber 2017). According to Cooke (2017), another factor that led to the agitation by the Ain Salah community is the concern that the indigenes feel neglected in terms of social and economic development of their region.

Another case worthy of note is that of the Muanda and Virunga Communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Muanda community predominantly depend on agriculture for their means of livelihood, and on several occasions have voiced their concerns regarding the environmental degradation caused by the activities of Perenco since operations began in 2002 (Petitjean 2014; Environmental Justice Atlas 2015). Another conflict still within the DRC is that between the communities bordering Virunga versus the Government and Soco International Plc (WWF Global 2014; BBC 2018). The Virunga community of the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2014 were agitated by the government’s approval for oil exploration activities to be carried out by Soco International Plc in their region, which also happens to be a World Heritage Site due to its habitation of endangered mountain gorillas, bush elephants and apes (WWF Global 2014). They made protests due to concerns that their agricultural activities, which serve as their major source of livelihood, will be affected by oil and gas projects in their region (WWF Global 2014; BBC 2018). They also expressed concerns that Soco did not provide them with enough information regarding the risks associated with the exploration activities (WWF Global 2014; BBC 2018).

Similarly, in Ghana where there were protests by the Keta community against the Government and Swiss African Oil company (FCWC 2018; Gadugah 2018). According to Gadugah (2018), indigenes of the region bordering the Keta basin had protested the prospective exploration activities in the area approved by the Government to be carried out by Swiss African Oil Company, a joint venture owned by Swiss African Petroleum Ag and PET Volta Investments. The residents in the region had concerns about the environmental impact of such exploration and its effect on the agricultural activities on which they depend for their livelihood (FCWC 2018; Gadugah 2018).

The conflict situation in Gabon between the communities around the Obangue River and Addax petroleum is also noted (Environmental Justice Atlas 2015). The Obangue River, which the communities depend on for their domestic and commercial purposes, was polluted due to Addax poor waste management practice, and resulted in series of protests by the communities (Environmental Justice Atlas 2015).

3. Establishing cordial relationships between oil companies and African host communities.

From the cases discussed above, it is evident that the industry has not fared well in managing their relationship with host communities in Africa where their operations are based and have not experienced to a fair degree the benefits of effective stakeholder management. Also, from the cases presented, one can deduce that the impact of poor stakeholder management on oil and gas companies would include: loss of reputation; violence and sabotage due to community protests; financial loss due to prohibitions of operations in the region backed by court orders. For instance in the Shell- Ogoni case, in addition to the $55 million agreed to be paid by Shell as compensation to the Bodo community for the oil spill, several agencies like the United Nations Environmental Programme, Business and Human Rights Resource Center and Amnesty International estimate that it will cost Shell $1bn to clean up the oil spill in the Bodo community (UNEP 2017; Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2015; Amnesty International 2015). Though each oil and gas company have policies and strategies in place regarding engaging with host communities, it is evident that these are not sufficient.

This research builds on the concept that a stakeholder will support you only if: 1. They feel they have been respected, 2. They feel their concerns were taken into consideration before decision-making, 3. They feel they will benefit from the decision in a fair way. If all these conditions are not met, then there will be issues with the stakeholder concerned.

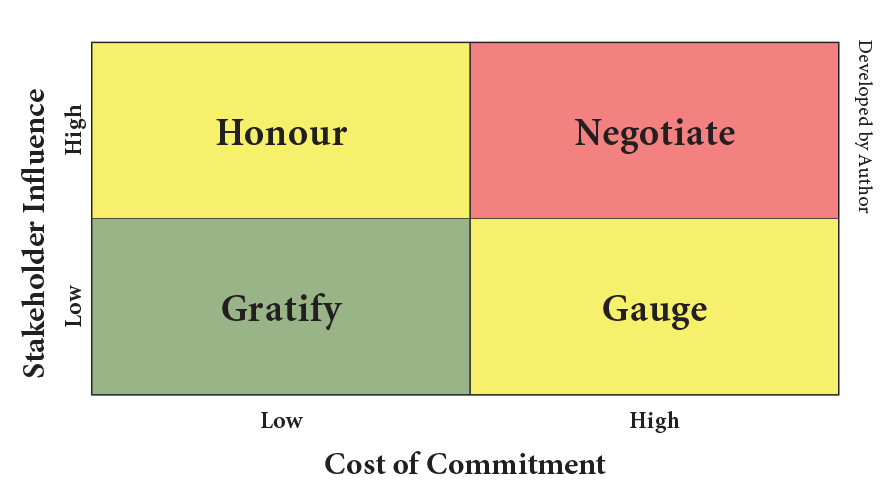

According to Wall (2012) and Orsini (2016), communities where oil and gas operations are based do have expectations that they will benefit socioeconomically from oil and gas projects in their region. Failure to effectively read, understand and fulfill these expectations will result in issues with the communities (Wall 2012; Orsini 2016). A key requirement regarding managing the relationships with host communities is to effectively consult and engage with the indigenes to understand their expectations, fears and concerns regarding planned operations and confirm that expectations will be met. Concerns must be resolved or managed, with appropriate reassurances to allay their fears before the decision to commence operations in the region is made. The essence of this, is to establish ‘trust’ between the oil companies and host communities. Opportunities must be provided for both parties to better understand the interdependencies that exists between them. A framework that could guide and inform the decisions of oil companies on how to effectively engage with host communities is the ‘Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix’ developed by the author of this article. The framework seeks to support managers in determining suitable approaches for engaging with stakeholders based on stakeholder influence and cost of commitment. The framework is similar to the Power Vs Interest Matrix developed by Mendelow (1991) in the sense that they both agree power (influence) is a key factor that should be considered when categorising and prioritising stakeholders. But the ‘Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix introduces an economic factor in place of ‘interest’ due to the fact several decisions made in the industry are mainly influenced by economic viewpoints. The cost of commitment refers to the overall monetary cost of meeting the expectations of, and sustaining the relationship with the stakeholder throughout the duration of the operation. Several researchers (Mistrot 1974; Duong 1984; Heydinger and Bovaird 1972) reveal that economic perspective is a major factor that informs decisions in the oil and gas industry. Hence, the Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix is a modification of Mendelow’s Power Vs Interest Matrix and provides a framework specifically tailored to the needs of the oil and gas industry. This will achieve effective categorisation of stakeholders and inform the engagement strategies to adopt factoring in economic requirements. The Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix is provided below:

Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix

The framework above provides managers with different approaches on how they could engage with stakeholders depending on their levels of influence and the costs for fulfilling the expectations of the parties concerned.

Based on the framework, the ‘Gratify’ approach should be used in situations where a stakeholder with low influence on the project/ operation is involved and the cost of fulfilling expectations of the stakeholder is low. The ‘Gratify’ approach requires that you swiftly proceed to resolving expressed concerns of the stakeholder and meet their expectations when and where required – bearing in mind that your project or operations might still be affected by the stakeholder though they may have low influence on the venture. The ‘Honour’ approach should be used when a stakeholder of high influence is involved and the cost of meeting the expectations of that stakeholder is low. The ‘Honour’ approach requires that you treat such stakeholders with utmost respect, bearing in mind the huge impact their actions could have on the venture. It will be beneficial if the expectations of the stakeholder are met – and prudently exceeded – in order to gain their trust, support and devotion to the success of the venture. The ‘Gauge’ approach should be adopted in cases when a stakeholder of low influence is involved and the cost of meeting expectation of the stakeholder is high. The ‘Gauge’ approach requires the identification and ranking of the concerns expressed by the stakeholder and determining the extent to which the organisation has the resources and capabilities to resolve the major concerns. The objective is to manage the expectations of the stakeholder while resolving the major concerns expressed. This will make them feel respected and have the impression that their concerns are being considered. The ‘Negotiate’ approach should be used when the stakeholder involved has high influence on the project/operation and the cost of fulfilling their expectations is high. Here, one must carefully liaise with the stakeholder, establish and enhance common grounds between the parties involved. This will allow for the understanding of interdependencies between the parties, establish trust and enable the successful execution of the project or operation.

In the case of the oil and gas industry, the host communities are seen as stakeholders with high influence (Reeman 2012; Mascarenhas 2011). This means that the ‘Honour’ and ‘Negotiate’ approach is more applicable when dealing with host communities, the appropriate approach between the two will depend on the cost of commitment. In the African host community context, cost of commitment would range from cost of alleviating the impact of industry operations within the region to the cost of providing community welfare benefits. It is also imperative to take into consideration the fact that new expectations and concerns from communities could emerge after operations have already commenced, but these should be monitored and managed in order to maintain favourable relationships with host communities – eliminating or mitigating risks of conflict. It will be beneficial for oil and gas companies to develop a vision on the positive nature they would want the relationship with host communities to take, and work towards its actualisation from both short and long-term perspectives.

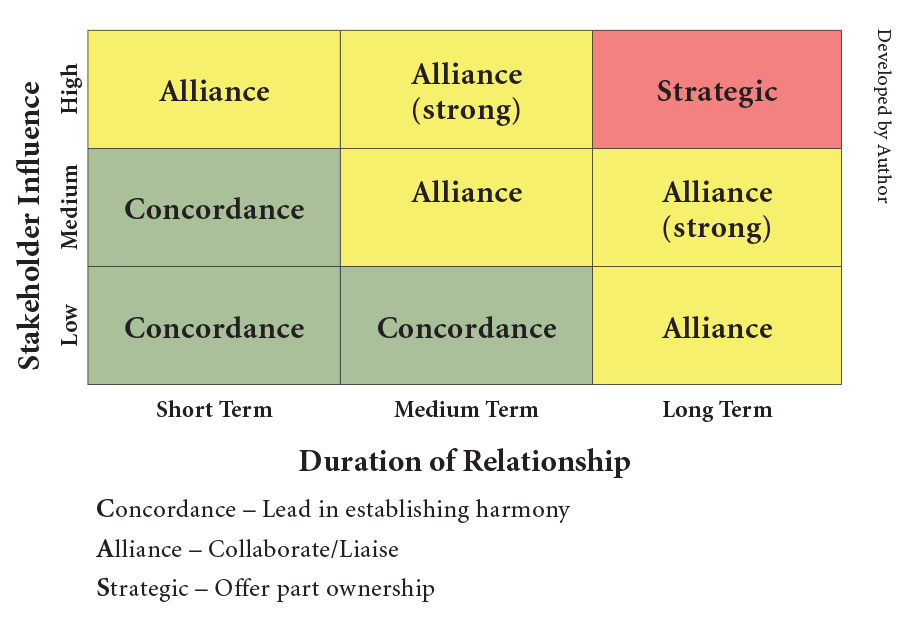

The CAS Matrix (Stakeholder Influence Vs Duration of Relationship), also developed by the author, provides guidance on the nature of the relationship that should exist between organisations and stakeholders – always considering the influence of the stakeholder and the duration of the project/operation. The CAS Matrix is presented in the following diagram.

CAS Matrix: Stakeholder Influence Vs Duration of Relationship

The ‘Concordance’ relationship should be established in situations where the stakeholder involved has medium to low influence on the venture and the duration of the project ranges from short to mid-term. This relationship requires the organisation to lead in establishing peace and harmony between the parties, to resolve any concerns expressed, and ensure an amicable affiliation between the parties throughout the duration of the project. The ‘Alliance’ relationship should be established in situations where the stakeholder has high level of influence on the project. This requires continuous collaboration between the parties involved in resolving concerns that would emanate before and during the project execution. The parties involved should see themselves as partners who will benefit from the venture, and work collaboratively towards its success and maximisation of benefits. The ‘Strategic’ relationship should be established in cases where the stakeholder has high influence on the project and the project has a long-term duration. This requires that the stakeholder involved be given part ownership of the project in order to lock in and sustain the interest and commitment of the stakeholder towards the success of the project.

In the case of the oil and gas industry, the ‘Alliance’ and ‘Strategic’ relationships are more applicable between oil companies and host communities in Africa due to the nature of the projects and operations carried out by the industry and the high influence these host communities have on such ventures.

As it has been acknowledged that most of the conflicts between oil and gas companies and host communities result from the impact of oil and gas operations on the communities (Reeman 2012; Mascarenhas 2011; Orsini 2016), it is important for oil and gas companies to ensure that part of their community engagement activities include periodic socioenvironmental impact assessments on their operations and provide host communities with adequate information regarding the impact of their activities. There must be agreement with communities on strategies to alleviate the impact of their operations. Where adequate information on the impact of operations is not provided, and where there is a failure to alleviate the impact of operations in the region, the result will be loss of trust in the oil company and increased conflict between both parties (Wall 2012).

Although the development and implementation of corporate social responsibility programmes (of which some oil and gas companies are known to be doing well in ) are encouraged in order for the communities to gain some benefits from the presence of industry operations in their region and to some extent cushion the effects of the impact of these operations, a sustainable and more effective means of establishing good relationship with host communities is by involving them in the ownership of operations and allocating them a share of the returns. This would encourage host communities to build trust in oil companies and naturally instill a sense of responsibility in them. This will further encourage host communities to cooperate and provide support towards the success of industry operations within their region. Though this concept would generally result in a cut in profits accruing to oil and gas companies, past experience (as in cases discussed earlier) has shown that costs resulting from conflicts between host communities and oil companies by far outweigh costs associated with establishing and improving relationships with host communities. Further, we must not forget the devastating effects this could cause on business continuity and the reputation of oil and gas companies both regionally and globally. Relationships between oil and gas companies and host communities could be further strengthened by both parties working collaboratively towards determining ways through which the benefits of the operations in host communities can be maximised and sustained. The underlying objective of all these, is to establish trust between host communities and oil companies, which will in turn make the host communities feel respected and assured that their concerns are, or will be taken into consideration in the decision-making process regarding operations in their region. They will also see that they will benefit fairly from the operations.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that effectively managing stakeholders associated with the value chain of oil and gas oriented business is very important for the success and continuation of organisations in the industry. The host communities, where oil and gas operations are based, are recognised to have significant influence on the success of these operations and are the entities, which are most seriously impacted by those operations. Though several Africa-based oil and gas companies have policies and strategies for engaging with host communities, it is evident that these have not been effective in establishing good relationships with host communities. This has been largely due to their inadequate and poor implementation, as seen in the cases discussed in this report. Apart from timely and continuous consultation with host communities to understand their concerns and expectations which should inform decisions regarding industry activities in their region, an effective means of establishing sustainable cordial relationship with host communities is by having them share in the ownership and profits of operations/projects in their region. Inasmuch as this may cause some reductions in the gross income of oil and gas companies, it is evident from the cases discussed in this report that the costs associated with conflicts between host communities and oil companies far outweigh the costs of implementing preventive measures to avoid conflicts between both parties, also taking into consideration the business/operational continuity risks and reputational damage the oil and gas company could face. By having host communities share in the ownership and profits of operations within their region, oil and gas companies will gain the trust and cooperation of host communities. Once trust has been established between both parties and their interdependencies understood, both parties would be encouraged to work collaboratively towards the continuous success of operations. At the same time, ways for maximising the benefits of the operations can be determined. These achievements will naturally result in cordial relationships being established and sustained. These measures are in line with the requirements of the Stakeholder Influence Vs Cost of Commitment Matrix and the CAS framework presented in this report – which categorises host communities as stakeholders of high influence. They will require a high-level approach of engagement that is distinguished by fairness, transparency and respect of rights.

5. Recommendations

Having recognised the significance of effectively engaging with and managing affairs with host communities where oil and gas operations are situated, it is recommended that ideas presented in this report be considered by oil and gas companies in the development of stakeholder engagement policies and strategies towards establishing sustainable cordial relationships with host communities in Africa and other stakeholders associated with the industry. It will be advantageous if the stakeholder engagement concepts proposed in this report are included in academic discussions concerned with licensing, policymaking, community relations and business strategy in the African context.

It is also recommended that additional research in this area that will include a comparative analysis of the nature of relationships that exist between oil companies and host communities in developed regions such as North America and Europe and those of developing regions such as Africa, South America and Asia be conducted. Such research could identify innovative ideas, effective tools and frameworks peculiar to the oil and gas industry that will further assist oil and gas organisations to establish sustainable cordial relationships with host communities where their operations are based.

Sources

Addax 2018 Community relations. Addax. Available from: <https://www.addaxpetroleum. com/social-responsibility/community-relations> [Accessed on 6 May 2018].

Ahmed, Jimmy 2019. Key to stakeholder relationship management in the oil and gas industry. Africa Oil and Gas Report, 27th December. Available from: <https://africaoilgasreport. com/2019/12/gas-monetization/key-to-successful-stakeholder-relationship-managementin-the-oil-and-gas-industry/> [Accessed on 2 March 2021].

Aljazeera 2016. Shell sued in UK for decades of oil spills in Nigeria. Aljazeera, 27th November. Available from: <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/11/shell-sued-uk-decades-oilspills-nigeria-161122193545741.html> [Accessed on 11 July 2018].

Amnesty International 2015. Investor warning: Shell profits won’t count true cost of Niger Delta oil spill. Amnesty International, 30th April. Available from: <https://www.amnesty. org/en/latest/news/2015/04/shell-profits-wont-count-true-cost-of-niger-delta-oil-spills/> [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Amnesty International 2017. Nigeria: Shell complicit in the arbitrary executions of Ogoni nine as writ served in Dutch Court. Amnesty International, 29th June. Available from: <https:// www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/06/shell-complicit-arbitrary-executions-ogoninine-writ-dutch-court/> [Accessed on 13.July 2018].

Association for Project Managers 2019. Stakeholder management. Association for Project Managers. Available from: <https://www.apm.org.uk/resources/find-a-resource/ stakeholder-engagement/#:~:text=Stakeholder%20Management%20is%20essentially%20 a,designed%20to%20engage%20with%20stakeholders%E2%80%9D> [Accessed on 20 April 2019].

Aubert, B. and Kelsey B. 2000. The illusion of trust and performance. CIRANO Working Papers.

BBC 2017. Nigeria: Ogoni widows sue Shell over military crackdown. BBC News, 29th June. Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-40443742> [Accessed on 11.July 2018].

BBC 2018. DR Congo explores oil drilling allowed in wildlife parks. BBC News, 30th June. Available from: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-44662326> [Accessed on 23 July 2018].

Boladeras, S, Wild, E, and Murphy,H. 2016. Oil and gas industry learning project on community grievance mechanisms. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 11th April. Available from: <https:// onepetro.org/SPEHSE/proceedings-abstract/16HSE/2-16HSE/D021S033R001/187158> [Accessed on 12 April 2018].

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2015. Messy Business: Nigeria’s delta oil spill clean-up will cost shell billions of dollars over 30 years. Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, 7th May. Available from: <https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/ latest-news/messy-business-nigerias-delta-oil-spill-clean-up-will-cost-shell-billions-ofdollars-over-30-years/> [Accessed on 5.March].

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre 2017. Shell lawsuit (Re oil spills and Bodo community in Nigeria). Available from: <https://business-humanrights.org/en/shelllawsuit-re-oil-spills-bodo-community-in-nigeria> [Accessed on 10.July 2018].

Chanya, Apipalakuk, Bouphan Prachaak and Keow Ngang 2013. Conflict management on use of watershed resources. Social and Behavioural Sciences, 136, pp. 481–485.

Chevron 2018. People – we put people at the centre of everything we do. Chevron. Available from: <https://www.chevron.com/corporate-responsibility/people> [Accessed on 6 May 2018].

Cooke, Keiran 2017. Algeria’s shale gas dreams are a nightmare for locals. Middle East Eye, 5th March. Available from: <https://www.middleeasteye.net/columns/algerias-shale-gasdreams-1208903436> [Accessed on 17.August 2018].

Daragahi, Borzou 2017. Environmental movement blocks fracking in Algeria’s remote south. Financial Times, 9th March. Available from: <https://www.ft.com/content/db622d4c-c0f611e4-88ca-00144feab7de> [Accessed on 20.August 2018].

De Oliveira, Gilberto Francisco and Roque Rabechini 2019. Stakeholder management influence on trust in a project: A Quantitative Study. International Journal of Project Management, 37 (1), pp. 131–144.

Dentchev, A. Nikolay and Aime Heen 2004. Managing the reputation of restructuring corporations: Send the right signal to the right stakeholder. Journal of Public Affairs, 4 (1), pp. 56–72.

Dooms, Michael 2019. Stakeholder management for port sustainability: Moving from adhoc to structural approaches. Green Ports, pp 63–84.

Dunham, W. Jon 2012. Effective stakeholder identification across arctic Alaska. OTC Arctic Technology Conference, 3rd December. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/ OTCARCTIC/proceedings-abstract/12OARC/All-12OARC/OTC-23853-MS/39687> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Duong, Ba-Tien 1984. Alberta economy from 1984 to 1995. Petroleum Society of Canada, 9th June. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/PETSOCATM/proceedings-abstract/84ATM/ All-84ATM/PETSOC-84-35-35/6348> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Eberhard, Mike and Robin Olsen 2014. Connecting with stakeholders. Journal of Petroleum Technology, 66 (10), pp. 24–25.

Environmental Justice Atlas 2015. Perenco Muanda Dem. Rep. Congo. Environmental Justice Atlas, 12th February Available from: <https://ejatlas.org/conflict/perenco-muanda-in-bascongo > [Assessed 18.July 2018].

Environmental Justice Atlas 2015. Pollution of the Obangue river (also Dubanga River) Gabon. Environmental Justice Atlas, 26th August. Available from: <https://ejatlas.org/conflict/ pollution-of-the-obangue-river-also-dubanga-river> [Accessed on 18.July 2018].

European Parliament – Directorate General for External Policies Department 2011. Effects of oil companies’ activities on the environment, health and development in sub-saharan Africa. European Parliament, 8th August. Available from: <http://www.europarl.europa. eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2011/433768/EXPO-DEVE_ET(2011)433768_EN.pdf> [Accessed on 28.May 2018].

ExxonMobil 2018. Managing community engagement. ExxonMobil. Available from: <http://corporate.exxonmobil.com/en/community/corporate-citizenship-report/ human-rights-and-managing-community-impacts/managing-socioeconomic-impactsand-risks?parentId=f1d5e90f-1506-4002-a9f4-b379a23f26ba> [Accessed on 6.May 2018].

FCWC 2018. Ghana: Angry residents protest oil exploration in Keta basin. FCWC, 16th May. Available from: <https://fcwc-fish.org/publications/news-from-the-region/1621-ghanaangry-residents-protest-oil-exploration-in-keta-basin.html> [Accessed on 23 July 2018].

Freeman, Ed 2014. Stakeholder management. Available from: <http://redwardfreeman.com/ stakeholder-management/> [Accessed on 5.May 2018].

Freeman, R. Edward 2010. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Fritz, Morgane M. C., Romana Rauter, Rupert J. Baumgartner and Nikolay Dentchev 2018. A supply chain perspective of stakeholder identification as a tool for responsible policy and decision-making. Environmental Science and Policy, 81, pp. 63–76.

Gadugah, N. 2018. Angry Keta residents protest oil exploration in Keta Basin. MyJoyOnline, 10th May. Available from: <https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/2018/May-10th/angryketa-residents-protest-over-oil-exploration-in-keta-basin.php> [Accessed on 23 July 2018].

Genter, Sabrina 2019. Stakeholder engagement in decommissioning process. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2nd December. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPESM02/ proceedings-abstract/20SM02/1-20SM02/D012S013R001/219456> [Accessed on 2 March 2021].

Henry, E. Anthony 2011. Understanding strategic management. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Heydinger, E. and W. Bovaird 1972. The economy – energy – oil to 1980 (Revisited) Society of Petroleum Engineers, 8th October. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEATCE/proceedings-abstract/72FM/All-72FM/SPE-4127-MS/164372> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Hinrich, V. 2014. Environmental public participation in the UK. International Journal of Social Quality, 4 (1), pp. 26–40.

Human Rights Watch 2003. Oil in southern Sudan. Human Rights Watch, June. Available from: <https://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/sudan1103/9.htm > [Accessed on 19.July 2018].

Jim, Smith and Peter E.D. Love 2004. Stakeholder management during project inception: Strategic needs analysis. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 10 (1), pp. 22–33.

Kabir, Rezaul and Hanh Minh Thai 2021. Key factors determining corporate social responsibility practices of Vietnamese firms and the joint effects of foreign ownership. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, March. Available from: <https://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1042444X20300657> [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Kinslow, Carla J. 2014. Hydraulic fracturing fools for successful engagement with fence-line communities. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 17th March. Available from: <https:// onepetro.org/SPEHSE/proceedings-abstract/14HSE/1-14HSE/D011S006R001/210856> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Lehtinen, Jere, Krisi Aaltonen and Risto Rajala 2019. Stakeholder management in complex product systems: practices and rationales for engagement and disengagement. Industrial Marketing Management, 79, pp. 58–70.

Leonidou, Erasmia, Micheal Christofi, Demetris Vrontis and Alkis Thrassou 2018. An integrative framework of stakeholder engagement for innovation management and entrepreneurship development. Journal of Business Research,119, pp 245–358.

Lester, Albert 2007. Project management, planning and control. Burlington, Elsevier

Linnen, Lyndsey T., Ahmed M. Abdelhakam Noureldin 2016. Social sustainability and stakeholder engagement: an international perspective. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 26th June. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/ASSPPDCE/proceedings-abstract/ASSE16/ All-ASSE16/ASSE-16-609/77163> [Accessed on 3rd March 2021].

Mascarenhas Audrey 2011. Community engagement. Society of Petroleum Engineers,

15th November. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEURCC/proceedingsabstract/11CURC/All-11CURC/SPE-149538-MS/150761> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Mayer, Roger C., Davis James H. and F. David Schoorman 1995. An integrative model of organisational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20 (3), pp. 709–734,

Mendelow, Aubrey 1991. Stakeholder mapping. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems, pp 407–418.

Mistrot, G. 1974. Engineering economy studies – some whys and wherefores. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 6th October. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEATCE/ proceedings-abstract/74FM/All-74FM/SPE-5077-MS/139553> [Accessed on 18 January 2019].

Mumma-Martinon, C. 2014. Effective engagement of stakeholders by oil and gas companies: a case of the stakeholder relationship management tool in Kenya. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 15th September. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEHSEA/proceedingsabstract/14HSEA/All-14HSEA/SPE-170574-MS/220515> [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Olawoyin Oladeinde 2017. Widows of Ogoni leaders killed by Abacha sue Shell in Netherlands. Premium Times, 29th June. Available from: <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/235331-%E2%80%8Ewidows-ogoni-leaders-killed-abacha-sue-shellnetherlands.html> [Accessed on 13.July 2018].

Orsini, Yadaira 2016. Learning from community-company conflicts: practical approaches.

Society of Petroleum Engineers, 11th April. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/

SPEHSE/proceedings-abstract/16HSE/2-16HSE/D021S019R001/187249> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Parshall, Joel 2014. Stakeholder issues play key role in shale future. Journal of Petroleum Technology, 66 (11), 78–84.

Perenco 2018. CSR. Perenco. Available from: < http://www.perenco.com/csr > [Accessed on 18 July 2018].

Petitjean, O. 2014. Perenco in the Democratic Republic of Congo: when oil makes the poor poorer. Multinationals Observatory, 1st September. Available from: <http:// multinationales.org/Perenco-in-the-Democratic-Republic> [Accessed on 19.July 2018].

Pilkington, Ed 2009. Shell pays out $15.5m over Saro-Wiwa killing. The Guardian, 9th June. Available from: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/jun/08/nigeria-usa> [Accessed on 10.July 2018].

Pollack, Jeffrey M., Barr Steve, and Hanson Sheila 2017. New venture creation as establishing stakeholder relationships: a trust-based perspective. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 7, pp. 15–20.

Pollard, Edward and Bennun Leon 2016. Who are biodiversity and ecosystem services stakeholders? Society of Petroleum Engineers, 11th April. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEHSE/proceedings-abstract/16HSE/316HSE/D032S068R004/187191> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Redvers, Louise 2012. Oil-rich Cabinda the poorer for it. M and G, 28th September. Available from <https://mg.co.za/article/2012-09-28-00-oil-rich-cabinda-the-poorer-for-it> [Accessed on 17.July 2018].

Reeman, Angela 2012. Social risk assessment as stakeholder engagement. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 11th September. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEHSE/proceedingsabstract/12HSE/All-12HSE/SPE-157194-MS/158580> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Rempel, J. , Holmes J. and Zana M. 1985. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, pp. 95–112.

Shah, Shashank and A. Sudhir Bhaskar 2008. Corporate stakeholder management western and Indian perspectives – an overview. Journal of Human Values, 14, (1), pp.73–93.

Shell 2018. Working with communities. Shell. Available from: <http://www.shell.com/ sustainability/communities/working-with-communities.html> [Accessed on 6 May 2018].

Shropshire, Christine and Amy J. Hillman 2007. A longitudinal study of significant change in stakeholder management. Business & Society, 46 (1), pp. 63 – 87.

Simon, A. and Weber L. 2017. Resistance to fracking projects, Algeria. Environmental Justice Atlas, 1st March. Available from: <https://ejatlas.org/conflict/resistance-to-frackingprojects-in-algeria> [Accessed on 20 August 2018].

Singh, Kuldeep and Madhvendra Misra 2021. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and organisational performance: the moderating effect of corporate reputation. European Research on Management and Business Economics, January. Available from:<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S244488342030320X> [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Soco International Plc 2018. Society. Soco International Plc. Available from: <https://www. socointernational.com/society> [Accessed on 24 July 2018].

UNEP 2017. UNEP Ogoni land oil assessment reveals extent of environmental contamination and threats to human health. UNEP, 7.August. Available from: <https://www.unep.org/ news-and-stories/story/unep-ogoniland-oil-assessment-reveals-extent-environmentalcontamination-and> [Accessed on 3 March 2021].

Vidal, John 2015. Shell announces £55m payout for Nigeria oil spills. The Guardian, 7th January. Available from: <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/07/ shell-announces-55m-payout-for-nigeria-oil-spills> [Accessed on 10.July 2018].

Wall, Caleb 2012. Managing community expectations through strategic stakeholder engagement. Society of Petroleum Engineers, 11th September. Available from: <https://onepetro.org/SPEHSE/proceedings-abstract/12HSE/All-12HSE/ SPE-153330-MS/157690> [Accessed on 18.January 2019].

Waronwant 2015. 20 years and still no justice: we remember the Ogoni nine. Waronwant, 9th November. Available from: <http://www.waronwant.org/media/20-years-and-still-nojustice-we-remember-ogoni-nine> [Accessed on 15.July 2018].

Watanabe, Lisa 2017. Algerian stability could fall with oil price. IPI Global Observatory, 18th May. Available from: <https://theglobalobservatory.org/2017/05/algeria-oil-priceislamism-protests/> [Accessed on 17.August 2018].

Webler, Thomas, Seth Tuler and Rob Kureger 2001. What is a good public participation process? Five perspectives from the public. Environmental Management, 27, pp. 435–450.

WWF Global 2014. Congolese protesters demand cancelation of Soco oil permits. WWF Global, 27th March. Available from: <http://www.wwf-congobasin.org/?218554/Congoleseprotesters-demand-cancelation-of-Soco-oil-permits> [Accessed on 23 July 2018].