Mr Billy Agwanda is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Marmara University. He has published several articles in international journals and book chapters. His interests include foreign policy, peace and conflict resolution, security, terrorism and counterterrorism.

Asst Prof Dr Uğur Yasin Asal is the Head of Political Science and International Relations Department at Istanbul Commerce University. His research interests include peace and conflict resolution and the intersection with political economy.

Abstract

Since the dissolution of the federal system in 1972, Cameroon has been entangled in an internal crisis between the Anglophone region and the government. After four years of violence, the outcome of peace efforts have largely been countered by more incidents of violence. This article traces how the crisis has evolved over the years from a political crisis into a conflict situation. While appreciating the theoretical perspectives of internal colonialism and ethnonationalism in explaining the conflict, the authors highlight that the evolution from a crisis into a conflict has been driven by factors such as the expanding waves of democratisation, the emergence of new actors (militias) and the evolution of the digital space (social media as platform for mobilisation). The article emphasises that whereas grievances over marginalisation form the underlying drivers of the conflict, disagreements over the judicial (common law) and education system in the Anglophone regions exacerbated the crisis, thereby leading to the outbreak of violence. Against this background, the article provides recommendations that may encourage a recourse to peace and stability for a nation previously lauded as one of the (few) stable countries in the Central Africa region.

1. Introduction

Africa feasibly represents an excellent embodiment of a paradox. This is because the presence of diverse cultural, linguistic, geographical, historical, and natural resources in the continent do not concur with the socio-political and economic conditions. Whereas the comparatively underachieving status of the continent can be attributed to several factors, colonial intervention with its concomitant slave trade, is one of the most significant experiences in the history of Africa (Agwanda and Ozoral 2020:57). The partitioning of Africa during the 1884 Berlin Conference as part of the colonial process, established an enduring legacy that continues to shape the social, economic, cultural, and political patterns in the continent.

The majority of African states emerged from the post-colonial era with a commitment to reverse the dark colonial legacy through ensuring economic development and providing social welfare to citizens. However, one glaring constraint was the heterogeneous nature of African societies that, for instance, deterred the selection of a single indigenous language to be used in public discourse. Additionally, the nature of public bureaucracies inherited at independence, meant that several African states had to continue relying on colonial languages. For many of the initial post-colonial leaders, replacing colonial languages with indigenous languages proved to be a pipe dream.

By such restructuring of Africa’s social and political structures, colonialism sowed the seeds of an identity crisis largely shaped around linguistic affiliations. The imposition of colonial dialects at the expense of indigenous languages, not only supported the colonial structures of exploitation, but have since evolved in the post-colonial era to create discord in various states within Africa. Moreover, the effects of the partition of Africa without input from Africans, and with the advancement of colonial languages, form part of the fundamental challenges facing post-colonial African states. Indeed, it is possible, albeit trivial, to speculate about what the contemporary status of the continent could have been if there were no colonial era.

More important than speculation, however, is the reality of the challenges facing states today. There are, for instance, the crises and conflicts of identity and language which have also been experienced in other parts of the globe. Conflict over language such as in education, communication in public spaces, access to state services, and even claim to citizenship, are increasingly becoming prominent. In several countries, particularly in Europe (Great Britain, Ireland, Belgium, Luxemburg, Switzerland, Ex-Yugoslavia and Catalonia) and the Americas (places such as Quebec), language has been a key factor in the rise of nationalism and conflict. In Catalonia for instance, there have been calls for the establishment of an independent Catalonian state because of, amongst other factors, the suppression of the Catalan language and identity by the state (Woolard 2013:210) This is a typical example of a clash between a dominant group with its identity and language, and a suppressed group with its identity and language. The dominant group treats its own members preferentially and fails to safeguard the political rights and the socio-cultural, and economic interests of the marginalised group. The fear and frustration of marginalised groups may be attributed to curtailed language rights (Nelde 2000:443). Ultimately, it is the propensity of language bias against minority groups that leads to, sustains, and exacerbates conflicts around language and identity. For minority groups, language is very sensitive as it creates a sense of community, culture, tradition or belonging – that is, language becomes the primary marker of membership to a community. At a more personal level, language make the difference between an individual having access to economic opportunities in the public sector or not.

A unique feature of the Cameroon conflict is that the clash of identities is not ethnic but rather about linguistic identity and is considered as one of the visible contemporary outcomes of colonial legacies in Africa. Distinguishing the conflict partly as a linguistic problem highlights the dynamics of language as a symbol of power and resource, and an instrument that can exacerbate conflict when there is a symbolic emphasis on one language in communication and writing over others; when language is used as an instrument to undermine the social and economic advancement of another group; and when used to consolidate economic and political power.

2. Theoretical framework

Several studies examining the Anglophone crisis (Keke 2020; Mougoue 2019) have explicated the crisis within the frameworks of internal colonialism and ethnonationalism. According to Hechter (1972: xiv), internal colonialism denotes the structural social, cultural, and political inequalities between different geographical regions in a particular state. These differences are usually characterised by conspicuous unequal distribution of economic resources, by political domination, and by cultural marginalisation. Howe (2002) argues that there can be additional factors such as language and religion that contribute to internal colonialism and the continuing uneven interactions between the core and the periphery. As a consequence, this unbalanced interaction eventually leads to the emergence of less advanced and more advanced groups within a society. While the more advanced groups strive to maintain the status quo through the institutionalisation of mechanisms, the less advanced groups struggle to change their circumstances, and this may reflect in the emergence or rise of a nationalistic consciousness. In Cameroon, cultural differences have been exploited by the Francophone dominated government to marginalise Anglophone regions. While terming this a ‘cultural division of labour,’ Hechter argues that a state can be directly involved through formulation of discriminatory policies and this influences groups to develop group consciousness about collective oppression either as political dominance or economic marginalisation, which is then perceived as unjust and illegitimate.

Secondly, other studies (Stevenson 1999; Fonchingong 2013) also highlight ethnonationalism as a framework for understanding the Anglophone conflict. Its proponents argue that the environment that surrounds an individual is determined by the structure of social identities and how these identities are perceived by the people (IkejianiClark 2009:27). Likewise, Cunningham (1998:2) emphasises that ethnonational identity is fundamental in conflicts because it influences the formation of in-groups and out-groups. These two arguments are central to identity-driven conflicts because, as noted by Walker Connor, ‘conflict is the divergences of basic identity, which manifests itself in the ‘us-them’ syndrome (Connor 1994:96). The ‘us’ versus ‘them’ is significantly applied in the Anglophone conflict.

However, there are certain variations in cultural, economic, and political issues common across Cameroon. As such, while internal colonisation and ethnonationalism provide bases for understanding the conflict, they fail to explain why 1) there has been a significant shift from a crisis situation to conflict since 2016; 2) only Anglophone regions are fighting for independence as opposed to Francophone regions that are also underdeveloped and marginalised. In light of these shortcomings, this article argues that the context, actors, and mobilisation techniques in the conflict have become more significant in their effects since the dissolution of federalism.

Generally, the end of the Cold War was critical to the decline of intrastate conflicts: as it removed ideological polarisation, starved the flow of material and financial resources to armed groups in developing countries, and restored the role of the UN (United Nations) in dealing with issues of global security. In the context of the Anglophone crisis, changes in the international system influenced preference for diplomatic domestic discourse in pursuing the Anglophone agenda. This was the case when for instance, Anglophone leaders petitioned the UN in 1995 to seek redress on the issue of independence. Additionally, the end of the Cold War inspired a new wave of democratisation in the global south. The introduction of multipartyism in Cameroon during the 1990s led to an increase in the degree of freedom of communication and association. Political parties and civil society groups therefore took up the Anglophone agenda.

Mobilisation techniques have also transformed and have become a critical component of the conflict. Increasingly, wider access to social media platforms has facilitated the mobilisation of thousands of young people who are actively engaged in the discussions surrounding issues of participating in mass protests and demonstrations. The diaspora communities have also been using social media platforms to raise funds for militia groups against the government. Two of such fundraising movements are ‘Adopt a Freedom Fighter’ – for a monthly minimum of USD 75, and ‘Feed the Nchang Shoe Boys’ (Human Rights Watch, 2018; World Association for Christian Communication, 2019). Social media platforms such as Facebook have been used by separatists and other civil society organisations in Anglophone Cameroon to document and expose human rights abuses by the government. Graphic videos of such atrocities instigate more anger and emotions by presenting government response as systematically pursuing a course of genocide in Anglophone Cameroon.

3. Creation of Cameroon

Like the majority of African states, Cameroon is a creation of the European colonial discourse. Diplomatic in its form and economic in fact, the 1884 Berlin Conference did not start the scramble for Africa but rather, established regulations for the complete conquest and partition of the continent which was already an ongoing process. The conference laid bare and legitimised the notion that Africa had become a political, social, and economic playground for European powers. While Africans maintained control over the hinterlands, the conference sparked movement of European powers away from the coastal regions to inland areas where jumbles of geometric boundaries were established and imposed over traditional boundaries and indigenous cultures.

Cameroon was under German occupation until World War I when it was conquered by the Allied powers and subsequently placed under disproportionate spheres of influence of France (East Cameroon) and Britain (West Cameroon) (Okereke 2018:8). Britain acquired a small strip representing 20% of Cameroon’s total land area along the border with Nigeria while France occupied 80% of the land area (Ngoh 1979:50). It is this disproportionate partition of Cameroon to Britain and France that led to the emergence of an Anglophone minority and a Francophone majority in Cameroon. The administration of Cameroon by Britain and France was nonetheless recognised internationally, firstly, as mandated territories of the League of Nations and later as UN trust territories (Dupraz 2019:633).

However, it is the post-World War II liberation wave blowing across the continent that ended colonial rule in Cameroon. France granted independence to the region under its sphere of influence, and the region became known as La Republique du Cameroun. For the British Southern and Northern Cameroon territories, a plebiscite was organised by the UN on February 11, 1961. The two questions on the referendum ballot were:

- Do you wish to achieve independence by joining the independent Federation of Nigeria?

- Do you wish to achieve independence by joining the independent Republic of Cameroon?

Table 1: The 1961 UN plebiscite results in Cameroon

| Choice | Northern Cameroon | Southern Cameroon | ||

| Votes | Percentage | Votes | Percentage | |

| Integration into Cameroon | 97 659 | 40 | 233 571 | 70.5 |

| Integration into Nigeria | 146 296 | 60 | 9 741 | 29.5 |

| Invalid Votes | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 243 955 | 100 | 331 312 | 100 |

| Registered Voters | 292 985 | 349 652 |

Northern Cameroonians voted in favour of a union with Nigeria, and key among their arguments was that it would have been senseless to discard the British lifestyle in favour of a French way of life (Johnson 2015:148). In Southern Cameroon, the overarching argument was that unification with Nigeria would result in a mass influx of the dominant Nigerian Igbos and, consequently, lead to loss of key employment and business opportunities. The Kamerun National Democratic Party argued that ‘…we have been with Nigeria for forty years under British administration. We have no roads, no government secondary schools. It is about time we try the other side of the border’ (Ngoh 1979:94). Ultimately, Southern Cameroon voted in favour of unification with La Republique du Cameroun in 1961.

The subsequent unification of Southern Cameroon with the Republic of Cameroon necessitated the establishment of structural governance modalities guaranteed by the constitution. This was initiated during a post-plebiscite meeting held in Foumban where it was established that the Republic of Cameroon would henceforth be referred to as East Cameroon; that Southern Cameroon would henceforth be referred to as West Cameroon; that the two regions would establish a new federation known as the Federal Republic of Cameroon; and, that the form of state and federal constitution could not be changed in future (Achankeng 2015:134). It is imperative to recognise that the unification process was not tantamount to a surrender of sovereignty by Southern Cameroon, but rather that it was a formal recognition of existence within the framework of a unitary state. The federal state was to maintain its judicial systems, economic structures, and education policies.

4. Dissolution of the federal republic and emergence of dissent

A decade after the creation of Cameroon, economic and political squabbles emerged between the federal government of West Cameroon and the national government. The strategic location of West Cameroon (Bakassi Peninsula) at the Gulf of Guinea, which is estimated to have the third largest oil reserves in West Africa (Baye 2010:11), became a natural resource target for the national government. Consequently, to have direct control of this natural resource, president Ahidjo Amadou organised another plebiscite in East Cameroon, that is Francophone dominated, to end the federation in 1972 (Takougang 2003:434). This unilateral decision was in contravention of the Foumban conference. Protests from Vice President Jonathan Foncha (from Anglophone Cameroon) only resulted in his dismissal from the executive. His replacement by Tandeng Muna from the Anglophone region, was in the capacity of Speaker of Parliament (Song 2015:123) and the position of Vice President was abolished, thereby, further centralising power in Cameroon.

The dissolution of the federal union, the elusive unity, and the government crackdown in Anglophone regions deterred open dissent against Francophone domination until 1982 when Paul Biya assumed power. Political reforms initiated by president Biya as part of the democratisation wave in the continent, provided an opportunity for the Anglophone political elites to voice long-standing grievances against Francophone domination (Takougang 2019:134). Firstly, protests erupted over the unilateral change of the name ‘United Republic of Cameroon’ to ‘Republic of Cameroon’. This new name was not only similar to the name Francophone Cameroon used before the unification, but also, seemed to have ignored that Cameroon is constituted of two distinct entities.

Due to rising frustrations in Anglophone Cameroon, the first opposition party – the Social Democratic Front (SDF) – emerged in 1990 and advocated for liberal political reforms (Krieger 2008:36). Unfortunately, the unveiling of the party in 1990 was marked by the death of six Anglophone youths after clashes with police (Krieger 2008:36). Supporters of SDF were instead accused by the government of advocating for the reintegration of Anglophone Cameroon with Nigeria by singing the Nigerian national anthem and carrying the Nigerian national flag (Konings 2004:185). The ruling Cameroon Peoples’ Democratic Movement (CPDM) criticised SDF and called for severe government response against the group and its supporters – whom they branded as ‘Biafrans’ (secessionists).

More pressure from the domestic and the international community on democratisation influenced Biya to declare multiparty politics and an increased degree of human rights and freedoms through the enactment of the Law of Association in 1990 (Law No. 90/056) (Ayuk 2018:47). It became more possible to arrange public rallies and demonstrations, and to disseminate information through newspapers. Consequently, other political parties, civil society organisations and associations emerged to actively represent the interests of the minority Anglophone communities both domestically and internationally.

5. Causes of conflict

Even though the contemporary aspects of the conflict can be traced to the shortcomings of the Amadou regime, its foundation is deeply rooted in the 1961 UN plebiscite. The protracted antagonism between West and East Cameroon has often motivated scholars to review the arguments justifying calls for either reconstitution of a federal system or secession of the Anglophone regions. These arguments can be classified into the following:

Socio-cultural victimisation. Feeling victimised by dominant sociocultural groups often establishes a strong sense of identity amongst minority groups – who may then develop coping mechanisms to facilitate their breakaway from such circumstances. Attempts by the government to reform the Anglo-Saxon cultural legacy in West Cameroon through the system of education are strongly resented. At the national level, students from Anglophone areas have often decried bias and discrimination in the admission processes at the higher institutions of learning (Chereji and Lohkoko 2012:13). After having had the Anglo-Saxon model in their primary and secondary schools, they would have a language drawback in a higher education that uses the French language and model. This has forced many students from Anglophone areas to travel abroad and seek education consistent with their earlier training while a majority of others fail to complete their studies in higher education.

Previously, as part of the government unification agenda, the Anglophone General Certificate of Education (GCE) had been modified to make it similar to that of the French baccalaureate. However, protests by teachers and students’ associations in West Cameroon prompted the government to establish a General Certificate of Education (GCE) board. In addition, while the Foumban accord provided for the recognition of English as an official language just like French, official communication in government and other public offices is often, if not exclusively, conducted in French regardless of the region. Media entertainment through television, cinemas, or theatres, were obligated to be in French – even in major Anglophone towns like Limbe and Bamenda. Programmes originally in English could only be broadcasted once dubbed translations of French were provided (Konings 2004).

Political grievances. Frustrations in West Cameroon have continued in the post-unification era when Francophone leadership has been alleged to dominate the government leaving minimal representation for the marginalised Anglophones (Caxton 2017:21). Since independence, the numerical dominance of Francophone Cameroon has ensured that the presidency is a de facto position for East Cameroon. The constitution however guarantees that if the president is from one of the regions, the prime minister must be appointed from the other region. As such, just like the presidency, the position of the prime minister has been a de facto post for Anglophone Cameroon. However, since Biya came to power in 1982, the office of the prime minister has been substantially weakened with more power vested in the office of the president. As such, most of the Anglophones feel that they are grossly underrepresented in government.

Secondly, for Anglophone Cameroonians, the concept of political sovereignty remains a distant reality. Perhaps the failure to grant independence to Southern Cameroonians as one of the options during the 1961 plebiscites may be considered as one of the continuing political grievances for the region. For Anglophone Cameroonians, there was a violation of the trusteeship agreement that was supposed to establish selfgovernment or lead to independence – as had been stipulated in Article 76(b) of the UN Charter Article that called for independence of former colonies in 1960.

Economic marginalisation. There is often a direct correlation between economic and political power (Gilens 2012:24) and control of economic resources is often subject to competition not only at the individual level, but also between various levels of government. West Cameroon is considered an important national economic base due to its natural resources such as oil and production of crops like bananas, tea, palm oil, cocoa, palms, timber, and rubber (Sama and Johnson-Ross 2005:104). The recognition of these attributes can be seen in the regional presence of the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC) – the biggest para-state corporation and the second largest source of employment after government (Wanie and Tanyi 2013:144).

Given these important economic attributes, one would perhaps expect that the region is privileged with meaningful development. However, lack of critical infrastructure such as roads, markets, and connectivity to electricity, has impacted productivity and forced the majority of the inhabitants into abject poverty (Pommerolle and Heungoup 2017:536). But even more significant, is the appropriation of oil revenues by the national government. All of Cameroon’s raw oil resources are located in the Anglophone region. But all the critical institutions such as the National Hydrocarbons Corporation (SNH), Cameroon Company of Petroleum Depots (SCDP), Hydrocarbon Analysis Control (HYDRAC), and the national refinery SONARA (Société Nationale de Raffinage) are located in the Francophone regions. For the inhabitants of Anglophone regions, establishing these corporations outside the region is perceived as a systematic plan by the government to deny the region employment opportunities.

6. From crisis to conflict

The political assimilation of the Anglophone region is hotly contested. In 1994, an All-Anglophone Conference was convened to implore the central government to either revert to the federal system or accept the demand for secession (Awasom 2007:155). This conference came up with resolutions in the form of the Buea Declaration that highlighted the stance of the territory by declaring that: ‘The common values, vision, and goals which we share as a people and those of our Francophone partners in the Union are different, and clearly cannot blend within the framework of a Unitary state such as was imposed on us in 1972. We are by nature pacifist, patient and tolerant and have demonstrated those qualities since we came into this Union. Our Francophone brothers believe in brutalising, torturing, maiming and assassinating dissenters. They have raped our women and daughters and used hand and rifle grenades against peaceful demonstrators. We find such barbarism alien to us and short of the civilised standards of all democratic societies’ (All-Anglophone Conference Standing Committee 1993:4–5).

This Conference marked the beginning of a new approach to the struggle for secession or federalism. This was promoted by various groups especially in the 1990s and appeared to be a period of re-enlightenment in the Anglophone territory. This is because one of the focus points of the Anglophone leadership (both political groupings and civil societies) was to transform the plight of the region – suffering under second-class treatment – from an elitist agenda to a collective group consciousness. As a strategy, this was meant to prepare and galvanise the masses through sensitisation campaigns for action in pursuit of either secession or federalism. The Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) became prominent for its agenda for secession.

In 1995, SCNC sought intervention of the UN to mediate between secessionist groups and the government and warned that failure would only lead to a sovereignty crisis (Lansford 2019:251). However, increased security crackdown by the central government disrupted the activities of the organisation. During one of its rallies in Bamenda, 200 people were arrested on allegations of attacking security officers. The arrested individuals admitted guilt, but Amnesty International drew attention to the fact that such admissions were obtained through torture (Europa 2003:162). The arrests and trial process ultimately led to the declaration of SCNC as an illegal organisation in Cameroon (Lansford 2019:251).

The state of despair within SCNC prompted Frederic Ebong, who was the organisation’s High Command Council chairman, to announce that independence had been restored for the Federal Republic of Southern Cameroon (FRSC) on 30th December 1999. This led to his immediate arrest and detention by the government. While he was in detention, other members of the FRSC through its Constituent Assembly met and deliberated on a set of state symbols such as flag, national anthem, and coat of arms to reflect the region’s purported independence. Between 2000 and 2015, a series of events increased the fragility of the situation, leading from a crisis to a more direct conflict from 2016. These events include:

Table 2: Selected key events between 2001 and 2015

| Year | Events |

| 2001 | Government bans Southern Cameroon National Council (SCNC) which was the largest grouping pushing for Anglophone region secession. |

| 2004 | Southern Cameroon National Council leader (Patrick Mbuwe) is assassinated. Government suspected.Security forces assault SDF leaders during protests.Crowds estimated at 50 000 people demonstrate following the death of an SDF member, John Khotem. |

| 2005 | Over 100 members of the SCNC are arrested without charge. They were gradually released through the rest of the year.50 members of the SCNC are arrested for purportedly holding an illegal meeting.Student-led protest for better opportunities in education for Anglophones turns violent.23 SCNC members are arrested by police. |

| 2006 | 65 SCNC members are arrested during a meeting.SDF parliamentary members walk out in protest of electoral bills for senators and councillors proposed by the Constitutional Law Committee. They demand an independent electoral commission.Two students are killed by police during protests over inequalities in education. |

| 2008 | A constitutional amendment is made to remove presidential term limits. |

| 2009 | AU Commission on Human Rights and Peoples Rights dismisses a petition by SCNC for independence. |

| 2010 | The 64th president of the UN General Assembly, Ali Triki presents two maps as gifts to Paul Biya showing the Republic of Cameroon (Francophone) and the other representing Anglophone Cameroon. Secessionists perceived this gesture as recognition of the independence of Southern Cameroon. |

| 2012 | SCNC announces plans to issue currency, identification cards and treasury bills in Anglophone regions. Plans are also announced for a petition against Cameroon’s ‘illegal’ occupation in Southern Cameroon. |

| 2014 | Republic of Cameroon organises and celebrates the 50th anniversary of the reunification. Anglophone Cameroonians detest this event and associate it with a distortion of history. |

| 2015 | All Anglophone Lawyers Conference themed around preserving Anglophone identity. |

The crisis took a turn in 2016 when frequent and violent clashes between separatist groups and the Cameroon government emerged. Clashes with security forces led to the death of twelve protesters in December 2016 and subsequently, an umbrella conglomerate of civil society organisations known as Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSC) was declared illegal (Amnesty International 2017). This escalation into conflict was exacerbated by two key events. First, the government appointment and deployment of Francophone judges (trained in Civil Law) to adjudicate over Common Law that is used in Anglophone Appellate courts.[1] The demand for lawyers to also file court cases in French in these courts sparked widespread protests from lawyers demanding the immediate reversal of such policies (JulesRoger 2018:23). Secondly, the appointment of teachers from Francophone Cameroon to work in Anglophone institutions without adequate knowledge of the English language also sparked protests by teachers, students, and activists.

The central government instead of adopting and emphasising diplomacy as the path to resolving the crisis, has often opted to apply force to crackdown protestors (Pommerolle and Heungoup 2017:532). In 2017, continued arbitrary arrests of activists and subsequent imprisonment led to the breakdown of negotiations meant to de-escalate the conflict. During the proclamation of independence of the Republic of Ambazonia that coincided with the Unification anniversary on 1st October 2017, security forces reportedly killed 20 protestors during the violent clashes and over 500 others were arrested.

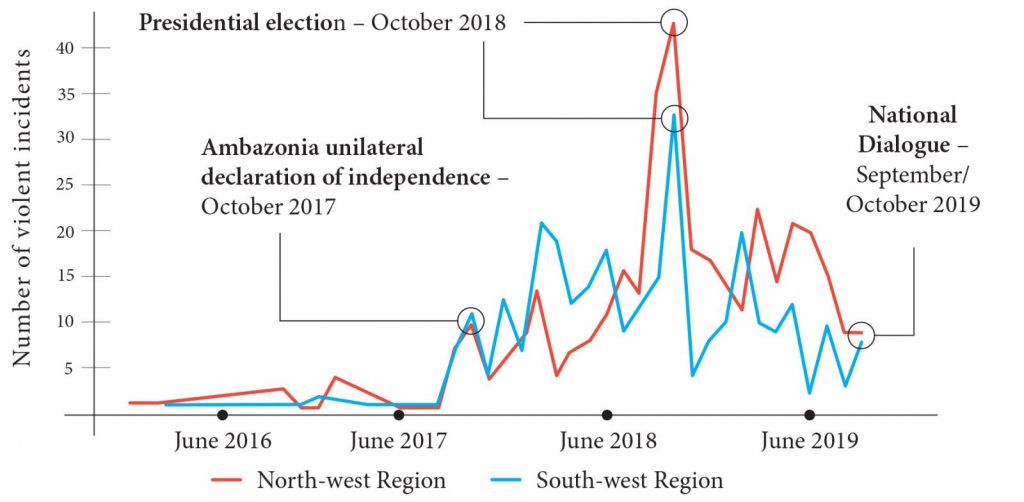

Figure 2: Violent events in Anglophone Cameroon (2016–2019)

Henceforth, retaliatory attacks on government institutions by armed militias have increased the presence of security apparatus in Anglophone regions. Some of the militia groups include Ambazonia Defence Force which is estimated to have approximately 300–500 fighters, and the Southern Cameroon Defence Forces (SOCADEF) that has approximately 400 militants (International Crisis Group 2019). Others are the Manyu Tigers (approx. 500 fighters); Red Dragons (approx. 400 militants); Seven Karta (approx. 200 fighters); Swords of Ambazonia and Ambaland Quifor (approx. 400 fighters); Ambazonia Restoration Army (few dozen fighters); and the Vipers (few dozen fighters). It is the emergence and activities of armed militia groups that have led to the increase in the number of people displaced internally (over 160 000) and externally (over 50 000) in 2017, that perhaps signified the transition of the Anglophone problem from a crisis into a conflict.

In 2018, clashes continued to escalate in the region after the arrest and forceful repatriation back to Cameroon of 47 Anglophone activists including the ‘interim President’ of the ‘Republic of Ambazonia’ and members of his Cabinet who had sought asylum from the government of Nigeria. Their subsequent detention as ‘terrorists’ triggered retaliations from militia groups who kidnapped over 40 civilian and government employees (Arieff 2018:4). By December 2018, violence between militia groups and the government had resulted in the displacement of approximately 550 000 people from Anglophone regions. This represents about 10% of the Anglophone population and positioned Cameroon as the sixth largest country with displaced population. Individuals fleeing the conflict, largely due to villages burned down by militia groups and government security agencies, have been forced to take shelter in forests. According to a report released by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance, more than 200 villages have either been completely or partially razed.

Often, some groups that are pushing for secession prefer to avoid targeting civilians. Studies such as Fazal (2018:161) argue that this is because such militia groups are concerned about their reputation within the international community and/or because they have no incentive to inflict harm on their surrounding populations – especially when their military capabilities cannot extend beyond their local geographies. However, for other Anglophone Cameroon separatist groups, targeting sections of the civilian population is a means of punishing those who ignore directives on issues such as boycotts and screening government sympathisers. For example, militia groups were identified as using machetes to cut off fingers of workers who did not boycott working on state-owned rubber farms. Several students were also kidnapped by separatist groups for failing to adhere to a school boycott order (Fazal 2018:161).

Militia groups have not only attacked government and civilians defying their orders, but also members of political groups supporting federalism. Ahead of the February 2020 elections, separatist militia groups attacked the party for not supporting the boycott of elections and withdrawing its parliamentary membership. According to Joseph Mbah who is a member of the SDF parliamentary group, ‘…SDF did not start its campaign on time in the Anglophone regions, because of the prevailing climate of intimidation and insecurity. Our members are being targeted by armed separatists. They have been kidnapped and threatened’ (Human Rights Watch 2020). In December 2019, more than 100 members of the SDF were kidnapped and all but six were released after a ransom was paid to the party. Generally, since 2016, the conflict has led to the loss of more than 3 000 lives, the displacement of more than 731 000 people and the denial of access to education for more than 600 000 children (Amnesty International 2020).

7. What is the way forward?

Resolving the Anglophone conflict in a sustainable manner will first and foremost require building trust between secessionists, government, and federalists and all the parties expressing a genuine desire to communicate through talking and listening. The government should take a lead in this regard because of its status as a legitimate actor with the capacity to convince the other actors in this conflict to engage in a genuine discussion. This does not necessarily mean that the parties will be expressing their unreserved commitment to resolve the conflict, but it may at least be a demonstration of an intent to build trust through actions marked by integrity and credibility.

Building trust can create an environment whereby the destruction of property by both government and armed militias in Anglophone areas can be brought to a halt and a path for constructive dialogue may be opened. The government should consider adopting a conciliatory voice, acknowledging the validity of Anglophone concerns, and considering the developing of a reparations policy for victims affected by the clashes between security officers and armed militia groups. Of great significance, the government should seek to refrain from making open demands and absolute statements about the form of (centralised) government as a precondition for dialogue with secessionists, even if it holds that the unity of Cameroon is non-negotiable. It is important to bring opposing groups to dialogue where consensus can be built. As a sign of good faith, Anglophone political activists who have been jailed should also be released.

The separatists on the other hand, should commence with internal negotiations that will persuade its members who have perhaps lost relatives during clashes with the government to understand that armed struggle will not attract international support, and will only serve to stain their image. This should also include urging members to abandon their previous calls for mass actions such as school and work boycotts, as a sign of good faith and of their will to dialogue with the government. Whereas the separatist will likely attempt to push for secession, they should also be willing to listen to other suggestions such as the option to abandon the claim for secession in exchange for more autonomy. It is also imperative that both the separatists and federalists engage in internal reconciliation so that they may develop a unity of purpose and a common stance towards potential solutions for the Anglophone grievances before engaging with the government in negotiations.

More and proactive international support should be mobilised to mediate in negotiations. Separatists do not recognise the legitimacy of the national government while the state does not tolerate any discussions short of a unified state. Getting to talk may therefore prove to be a cumbersome task. Consequently, the influence of the international community is central to negotiations. The African Union, as an active guarantor of African peace and security should take a leading role in attempting to mediate a solution either directly or through supporting the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). There needs to be appreciation of the possibility that volatility in Cameroon can spread and become a larger transnational crisis with ramifications for both Cameroon and the larger central Africa region. The African Union as a continental body must become bold and apply more pressure on the Cameroonian government to respect human rights and freedoms, including frequent fact-finding visits to the Anglophone regions to timeously assess the situation.

External security partners to the continent such as the United States, United Kingdom (UK) and France need to act more decisively on behalf of the international community to bring both sides to dialogue. The UK and the UN are historical actors in this conflict; France has sway over the central government while the US is a significant security partner for Cameroon in the war against Boko Haram. They are therefore in a prime position to keep pressure on both the government and the separatist groups to engage in a genuine conversation and reform to a system of governance that is inclusive. The US, UK and France, being permanent members of the UN Security Council, should petition the UN Human Rights Council to adopt the Anglophone Conflict into its main security agenda as current trends indicate that the conflict can threaten international peace and security since the region also suffers extensively from the Boko Haram threat. Moreover, the UN Human Rights division should actively investigate claims of violations of human rights by both government and the separatist militia groups.

The government of Cameroon must also commit to undertake key institutional reforms in governance. The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance adopted by the AU in 2007, presents an ideal referential framework to guide sustainable political reforms in Cameroon. This article has demonstrated that one of the underlying causes of political dissent is the failure for the government to uphold the treaty on federalism as was envisaged during the unification era. It is therefore appropriate, that the government reconsider a federalism that is supported by institutional frameworks guiding cooperation between national and federal governments. Such a framework ought to be established with provision for equitable revenue allocation, clear separation of powers between the federal states and the national government, as well as a guarantee of a free political ecosystem where grievances can be raised and rights to peaceful dissent are respected.

The various interactions between communities in the Anglophone regions with the police have resulted in several allegations that security forces have demonstrated total disregard of human rights and freedoms and have been involved in the death of several civilians. Such allegations are far-reaching and if proven true, would be in direct contravention of international laws on the protection of human rights and freedoms, particularly with respect to the sacred right to life. Pursuing a course of justice for the victims of police brutality falls within the capabilities of the Cameroon government. As such, it is imperative that the government commit itself to undertaking impartial and speedy investigations so that security officers found culpable of violating these rights are charged under the existing judicial laws that guide the conduct of security officers. Additionally, the central government that has a monopoly over the use of force must ensure that all security operations conducted in the Anglophone region adhere to the provision of international human rights and freedoms. Importantly, there is need for the security operations to uphold the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Firearms. The government can also deploy judicial police officers to monitor such security operations.

For progress to occur, three scenarios, based on the efforts put forward towards resolving the conflict, may be considered. At best: the conflict can be resolved through a politically negotiated settlement that will see the re-establishment of the previously conceived federal system at independence. This will perhaps highlight the utmost commitment of the government to re-establish peace in the country and significantly contribute to other efforts to deal with security threats posed by terrorist groups such as al-Shaabab in the northern regions of Cameroon.

Secondly, the most likely is a reform scenario: radical change to federalism will be suppressed, but there will be some allowance for decentralisation and promotion of both official languages. The government will then rigidly insist on its mandated power, guaranteed under national, regional, and international laws on self-determination. The issuance of a presidential decree in 2018, establishing the Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development indicates a partial reform agenda. Further reforms would include acceleration of decentralisation through implementation of the General Code of Regional and Local Authorities which allocates ‘Special Status’ to Anglophone regions as well as the Promotion of Official Languages in Cameroon that designates both English and French as official languages in all public institutions. These concessionary moves may well succeed in pacifying groups calling for the re-establishment of the federal system, but radical secessionists are likely to continue in the near future.

The third scenario, considered by this article as the worst, would be the failure to achieve any significant progress in the implementation of political, economic, and social reforms by the government and a subsequent outcome would be continuous attacks on government institutions by militia groups or a significant increase in civilian casualties from the conflict between the state and armed groups. This can trigger a much larger possibility of violent unrest in Anglophone regions, thereby leading to violent civil war. This article emphasises that the ideal solution would be a middle-ground reached on concessions from both the government by implementing political, economic, and social reforms, and abstinence from further attacks by armed groups. Equally, we discourage a secessionist agenda because it will not only attract strong opposition from the state, but also because it would set a dangerous precedent, especially for regions already challenged by other secessionist groups, such as Biafra.

8. Conclusion

The conflict has for several decades impacted a lot of people either directly or indirectly in Cameroon and it is necessary that a lasting solution be found. Compared with reactions to other conflicts in the continent, such as to the South Sudan conflict (Rolandsen 2015), the Somali conflict (Nyadera, Ahmed and Agwanda 2019) and the Boko Haram conflict (Nyadera and Bincof 2019), international response to the Anglophone conflict remains minimal. A few European countries (the UK, France and Germany) and the US have only from time to time issued statements calling the government and separatist groups to negotiate. On the multilateral front, the UN is also yet to take concrete measures to resolve the conflict. Attempts by Norway and Netherlands to introduce it as an agenda item in the UN Security Council were shot down(defeated) after failing to garner the minimum 9 out of 15 of the votes. Côte d’Ivoire, China, Ethiopia, France, Russia, and Equatorial Guinea all voted against.

However, while this article places an emphasis on the potential role of external actors in facilitating a solution to the conflict, the authors underline that an internal national dialogue initiated by the government in collaboration with dissenting groups, particularly from Anglophone Cameroon regions, hold the key to finding a sustainable solution. To initiate such a process at a national level, the government must extend a hand and demonstrate goodwill by ensuring that political detainees are released or given access to all the rights of accused persons including the right to legal representation. Separatist groups must also cease from engaging in illegal activities such as targeting government installations and kidnapping individuals suspected to be pro-government. These concessions can provide a good foundation upon which a process of national dialogue can be initiated and advanced.

Sources

Achankeng, Fonkem 2015. The Foumban constitutional talks and prior intentions of negotiating: A historico-theoretical analysis of a false negotiation and the ramifications for political developments in Cameroon. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective, 9 (2), p. 11.

Africa Elections Database 1960. 1960 Elections in Cameroon. Available from: <http://africanelections.tripod.com/cm.html> [Accessed 14 June 2020].

Agwanda, Billy and Basak Özoral 2020. The sixth zone: Historical roots of African diaspora and Pan-Africanism in African development. Journal of Universal History Studies, 3 (1), pp. 53–72.

All Anglophone Conference Standing Committee 1993. The Buea Declaration. Limbe. Nooremac Press.

Amnesty International 2017. Cameroon: Arrests and civil society bans risk inflaming tensions in English-speaking regions. Available from: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/pressreleases/2017/01cameroon-arrests-and-civil-society-bans-risk-inflaming-tensions-inenglish-speaking-regions/> [Accessed 14 June 2020].

Amnesty International 2020. Cameroon: Rise in killings in Anglophone regions ahead of parliamentary elections. Available from: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/02/cameroon-rise-in-killings-in-anglophone-regions/> [Accessed 15 June 2020].

Arieff, Alexis 2018. Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis: Recent developments and issues for Congress. Washington D.C. CRS Insight, IN10881, 6.

Armed Conflict and Location Event Data 2019. (ACLED). Crackdowns, ‘ghost-towns’, and violence against civilians in Anglophone Cameroon. Available from: <https://acleddata.com/2019/02/14/crackdowns-ghost-towns-and-violence-against-civilians-inanglophone-cameroon/> [Accessed 14 June 2020].

Awasom, Nico F. 2007. Language and citizenship in Anglophone Cameroon. In: Nugent, Paul, Daniel Hammett, and Sara Dorman eds. Making nations, creating strangers: States and citizenship in Africa. Leiden, Brill, pp. 143–160.

Ayuk, Augustine E. 2018. The roots of stability and instability in Cameroon. In: Takougang, Joseph and Julius A. Amin eds. Post-Colonial Cameroon: Politics, Economy, and Society.

Baye, Francis 2010. Implications of the Bakassi conflict resolution for Cameroon. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 10 (1), pp. 9–34.

Caxton, Atek, S. 2017. The Anglophone dilemma in Cameroon: The need for comprehensive dialogue and reform. Conflict Trends, 2017 (2), pp. 18–26.

Chereji, Christian-Radu and Emmanuel A. Lohkoko 2012. Cameroon: The Anglophone problem. Conflict Studies Quarterly, 1, pp. 3–23.

Connor, Walker A., 1994. Nation is a nation, is a state, is an ethnic group, is a…/ In: Connor Walker ed. Ethnonationalism: The Quest for Understanding, pp. 90–117.

Cunningham, William G. 1998. Conflict theory and the conflict in Northern Ireland. MA Thesis. Auckland. University of Auckland.

Dupraz, Yannick 2019. French and British colonial legacies in education: Evidence from the partition of Cameroon. The Journal of Economic History, 79 (3), pp. 628–668.

Europa Publications, 2003. Africa south of the Sahara 2004. London. Psychology Press. Fazal, Tanisha M. 2018. Wars of law: Unintended consequences in the regulation of armed conflict. Ithaka, Cornell University Press.

Fonchingong, Tangie 2013. The quest for autonomy: The case of Anglophone Cameroon. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 7 (5), pp. 224–236.

Gilens, Martin 2012. Affluence and influence: Economic inequality and political power in America. Princeton. Princeton University Press.

Hechter, Michael 1972. Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development.

New Brunswick. Transaction Publishers.

Howe, Stephen 2002. Ireland and empire: colonial legacies in Irish history and culture. New York. Oxford University Press.

Human Rights Watch 2018. ‘These killings can be stopped’: Abuses by Government and separatist groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions. Available from:<https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/cameroon0718_web2.pdf> [Accessed 15 June 2020].

Human Rights Watch 2020. Cameroon: Election violence in Anglophone regions. Available from: <https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/02/12/cameroon-election-violence-anglophoneregions> [Accessed 15 June 2020].

Ikejiani-Clark, Miriam ed. 2009. Peace studies and conflict resolution in Nigeria: A reader.

Ibadan. Spectrum Books.

International Crisis Group (ICG) 2019. Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: How to Get to Talks?.

Available from: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/cameroon/272-criseanglophone-au-cameroun-comment-arriver-aux-pourparlers> [Accessed 14 June 2020].

Johnson, Willard R. 2015. The Cameroon Federation: Political integration in a fragmentary society (Vol. 1434). Princeton. Princeton University Press.

Jules-Roger, Sombaye E. 2018. Inside the virtual Ambazonia: Separatism, hate speech, disinformation and diaspora in the Cameroonian Anglophone crisis. MA Thesis. University of San Fransisco.

Keke, R.C., 2020. Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia conflict: A political economy. Theory & Event, 23 (2), pp. 329–351.

Konings, Piet 2004. Opposition and social-democratic change in Africa: the Social Democratic Front in Cameroon. Commonwealth & comparative politics, 42 (3), pp. 289–311.

Krieger, Milton 2008. Cameroon’s Social Democratic Front: Its history and prospects as an opposition political party (1990-2011). Bamenda. African Books Collective.

Lansford, Tom 2019. Cameroon. In: Lansford, Tom ed. Political Handbook of the World 2018–2019, Thousand Oaks, CA, CQ Press, pp. 247–257.

Le Vine, Victor T. 1961. The Cameroons: From mandate to independence. Sacramento. University of California Press.

Le Vine, Victor T. 1975. Leadership transition in Black Africa: Elite generations and political succession. Munger Africana Library Notes, 30, pp. 1–67.

Mougoué, Jacqueline-Bethel T. 2019. Gender, separatist politics, and embodied nationalism in Cameroon. Michigan. University of Michigan Press.

Nelde, Peter 2000. Prerequisites for a new European language policy. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21 (5), pp. 442–450.

Ngoh, Victor J. 1979. The political evolution of Cameroon, 1884-1961. Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2929. Oregon. Portland State University.

Nyadera, Israel N. and Mohamed O. Bincof 2019. Human security, terrorism, and counterterrorism: Boko Haram and the Taliban. International Journal on World Peace, 36 (1), pp. 4–15.

Nyadera, Israel N., Salah A. Mohamed and Billy Agwanda 2019. Transformation of the Somali civil-war and reflections for a social contract peacebuilding process. Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences 18 (4), pp. 1346–1366.

Okereke, Nna-Emeka C. 2018. Analysing Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 10 (3), pp. 8–12.

Pommerolle, Marie-Emmanuelle and Hans De Maries Heungoup 2017. The ‘Anglophone crisis’: A tale of the Cameroonian postcolony. African Affairs, 116 (464), pp. 526–538.

Rolandsen, Øystein H. 2015. Another civil war in South Sudan: The failure of guerrilla government? Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9 (1), pp. 163–174.

Sama, Molem C. and Deborah Johnson-Ross 2005. Reclaiming the Bakassi Kingdom: The Anglophone Cameroon–Nigeria border. Afrika Zamani, 13 (14), pp. 103–122.

Song, Womai I. 2015. The Clash of the Titans: Augustine Ngom Jua, Solomon Tandeng Muna, and the politics of transition in post-colonial Anglophone Cameroon, 1961-1972.Doctoral dissertation, Howard University.

Stevenson, Garth 1999. Community besieged: The Anglophone minority and the politics of Quebec. Montreal. McGill-Queen’s Press.

Takougang, Joseph 2003. Nationalism, democratisation and political opportunism in Cameroon. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 21 (3), pp. 427–445.

Takougang, Joseph 2019. African state and society in the 1990s: Cameroon’s political crossroads. New York, Routledge.

Wanie, Clarkson Mvo, and F.O. Tanyi 2013. The impact of globalisation on agro-based corporations in Cameroon: the case of the Cameroon Development Corporation in the South West region. International Journal of Business and Globalisation 11 (2), pp. 136–148. Woolard, Kathryn A. 2013. Is the personal political? Chronotopes and changing stances toward Catalan language and identity. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 16 (2), pp. 210–224.

World Association for Christian Communication (WACC) 2019. Media and conflict in Cameroon today. Available from: <http://www.waccglobal.org/articles/media-andconflict-in-cameroon-today> [Accessed 26 October 2020].

Sen, Amartya 2006. Identity and violence: The illusion of destiny. London, Penguin Books. Sezgin, Erkan 2007. Formation of the concept of terrorism. In: Ozeren, Suleyman, G. Ismail Dincer and M. Diab Al-Badayneh eds. Understanding terrorism: Analysis of sociological and psychological aspects. Amsterdam, IOS Press.

Southers, Erroll 2013. Homegrown violent extremism. Amsterdam, Elsevier.

Tamir, Yael 2019. Why nationalism. Princeton and Oxford, Princeton University Press.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies 2020, Ethiopia’s factional politics. April 2020. Available from: <https://www.iiss.org> [Accessed 10 May 2020]. The New Humanitarian 2019. Power shift creates new tensions and Tigrayan fears in Ethiopia.

The New Humanitarian, 14 February. Available from: <http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2019/02/14/Ethiopia-ethnic-displacement-power-shift-raises-tensions> [Accessed 9 December 2019].

Tilly, Charles 1990. Coercion, capital, and European states: AD 990–1990. Oxford, Basil Blackwell.

Tsega, Eteffa 2019. The origins of ethnic conflict in Africa politics and violence in Darfur, Oromia, and the Tana Delta. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

United Nations 2017. World Population Prospects: Key findings & advance tables, United Nations, 2017 Revision. Available from: <https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/ Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf> [Accessed 29 November 2019].

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2017. Preventing violent extremism through education: A Guide for Policy-Makers. Paris, UNESCO.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) 2018. EthiopiaSomali Region inter-communal conflict: Flash update Number 1, 17 August. Available from: <https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-somali-region-inter-communalconflict-flash-update-number-1-17-august-2018> [Accessed 30 December 2019].

United Nations Population Fund 2020. World Population Dashboard: Ethiopia. Available from: <https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/ET#> [Accessed 3 June 2020]. Washington Post 2018. In Ethiopian leader’s new cabinet, half the ministers are women. Washington Post, 16 October. Available from: <https://www.washingtonpost.com/ world/africa/ethiopias-reformist-leader-inaugurates-new-cabinet-half-of-theministers-women/2018/10/16/b5002e7a-d127-11e8-b2d2-f397227b43f0_story.html> [Accessed 20 August 2019].

Williams, Paul 2011. War and conflict in Africa. London, Polity Press.

Yonas, Adaye 2014. Conflict complexity in Ethiopia: Case study of Gambella Regional State.

Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bradford, Bradford.

Endnotes

[1] The Common law system is based on the concept of a judicial precedent. Judges take an active role in shaping the law since the decisions a court makes are then used as a precedent for future cases. Whilst common law systems have laws that are created by legislators, it is up to judges to rely on precedents set by previous courts to interpret those laws and apply them to individual cases. Civil law systems, on the other hand, place much less emphasis on precedent than they do on the codification of the law. Civil law systems rely on written statutes and other legal codes that are constantly updated and which establish legal procedures, punishments, and what can and cannot be brought before a court.