Dr Kelemework Tafere Reda is a Visiting Researcher at the Institute of Dispute Resolution in Africa (IDRA), University of South Africa (UNISA).

Abstract

Land is a contentious resource in the pastoral areas of Ethiopia. Traditional pastoralism, which is both a mode of production and a cultural way of life, dictates communal ownership of grazing land on which individually owned livestock graze. Pastoral land in Afar has traditionally been administered by the local communities themselves. However, with a gradual incorporation of the pastoralists into the Ethiopian modern polity, there have been competitive interests over issues of land administration between local communities and the state which often led to conflict and instability. Government land administration policies often contravene the age-old pastoral customary institutions; and stakeholder relations have taken a bitter course following the expansion of commercial agriculture, land investments and development projects. Using data obtained through Qualitative Interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) this paper analyses land administration trajectories and dynamics in Afar region. It assesses how contradictions between statutory and customary tenure systems shape relations between multiple resource users including the state, investors, local communities, and neighbouring cultural groups. It also examines the impact of multi-stakeholder land disputes on land resource management, thereby identifying appropriate policy options for effective land administration practices in the pastoral areas.

Introduction

Pastoralism with livestock husbandry as its main feature has existed for many centuries in the Horn of Africa region and East Africa as a whole. Ethiopia is home to ten million pastoralists who occupy over 61 per cent of the country’s land mass. They are found in seven of the twelve regional states in Ethiopia and occupy the most inhospitable arid and semi-arid environments characterised by high temperature and low and erratic rainfall patterns (Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia 2010), often with an annual rainfall of less than 500-750 mm (Markakis 2004:4). At present, pastoralists find it difficult to make efficient use of their land resources due to internal and external factors pertinent to land tenure and use. Development policies of the 1970s and 1980s have actually failed to recognise customary rights of pastoralists to land (Cotula et al. 2004:23).

The Afar, who belong to two groups of distinct descent (Getachew 2001), are one of the largest pastoral groups in the Horn of Africa. They are found in Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti. Their population in Ethiopia is 1 390 273 and they occupy an area of 96 707 square kilometres (Central Statistical Authority 2008). In terms of Ethnic composition, the majority (i.e. over 90%) are Afar; but there are also settlers from other ethnic groups. These include Amhara, 5.22%; Argoba, 1.55%; Tigrayans, 1.15%; Oromo, 0.61%; Welayta, 0.59%; and Hadya, 0.18% (CSA 2008).

The Afar region is one of the poorest, drought-affected and least developed regions of Ethiopia, and is neglected by national development initiatives (Guinand 2000; Piguet 2002). It is only in recent years that efforts have been undertaken to provide basic infrastructure such as roads and administrative buildings as well as education and basic health services. However, despite these positive developments, pastoralists in Ethiopia are facing the problem of land grabbing and the new agrarian colonialism (Galaty 2011:6).

Research question and methodology

The study upon which this report is based employed qualitative approaches of data collection with ethnography as the principal research method. The fundamental research question was: How do the dynamics in land tenure and land governance shape relations between stakeholders in the Afar region? Hence the specific objectives were 1) to examine the formal and informal land tenure systems in Afar region, 2) to analyse the dynamics in land use and land administration from the point of view of local communities, 3) to examine government attitudes and policies on land use and administration, 4) to examine emerging disputes among stakeholders as a result of changes in land use and administration practices.

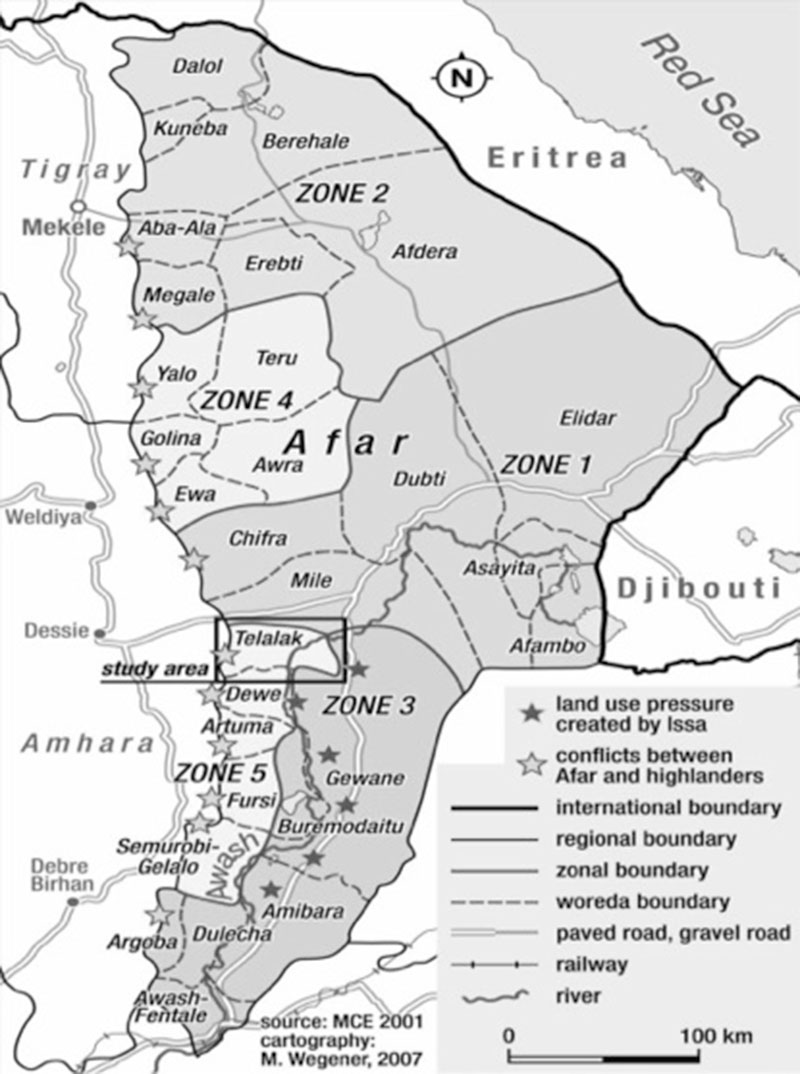

Fieldwork was conducted on a sample of nine districts of the Afar region. These were Awash, Assayta, Dubti, Chifra, Kuneba, Ab’ala, Amibara, Gewane and Ewa. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with forty five knowledgeable key informants selected from the nine districts. A total of eighteen Focus Group Discussions (two FGDs in each district) were also conducted to ascertain community views and practices. Each focus group was composed of eight to ten participants representing the different sections of the community in terms of age, gender and socio-economic status. There was also a total of nine informants from the local Woreda1 administrations in order to understand the government’s perspectives. The findings of the study are presented below in the form of descriptive narratives. The quotations presented in the text emanated from the Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and key-informant interviews and are representative of the overall feedback obtained from respondents during the fieldwork period.

Map 1: Location of conflict prone areas involving Afar and other groups.

The formal and informal tenure systems

According to informants, water, grazing land and forests are key resources in the Afar lowlands. Land is particularly perceived by the Afar pastoralists as the most indispensable asset, as it, together with livestock, plays an indispensible role in times of life and death, conflict and peace, happiness, misery and sadness.

There are typically two types of land tenure systems that have crystallised over the course of time. The first is the formal system which is based on policies, laws and proclamations put in place by the federal and regional governments.

The second relates to informal tenure, in which land boundaries and rules of resource use and administration are traditionally defined on the basis of clan-based social organisation. The latter operates in accordance with existing customary norms and value systems.

The formal tenure systems are more recent and are an extension of the government’s experience with agrarian societies in the highland parts of Ethiopia. As Helland (2006) points out, the fact that pastoral land tenure received less attention in the country’s constitution and overall public policy is indicative of the fact that pastoralists have been socially and politically marginalised.

In the context of the Afar, the customary and government tenure systems are in frequent interaction with one another and have been subject to the influence of various socio-economic, cultural and political factors. The informal tenure system has hitherto been dominant and has not been in concurrence with government tenure approaches that place emphasis on harmonised national level land use rights to households. Except in the case of land taken by the government for development projects and specific plots apportioned for investors (which for the most part still remains in the custody of clan heads), most other land is communally administered and is predominantly used for communal livestock grazing. Grazing land and forest reserves have long been governed by the sultanate2 or/and clan-based institutions. Each clan and sub-clan has its own territory and access by others is subject to prior mutual consent.

Formal and informal tenure systems have their own strengths and weaknesses. For example, although land is deemed to be communally owned under the traditional pastoral tenure system, there is often a problem of equitability. The customary institutions are mainly based on a clan system in which clan territories provide the framework for land resource utilisation, management and administration. This kind of clan-based territorial land resource use and administration can potentially have a negative impact on fair and sustainable resource distribution, use and management in the region. In the customary arrangement, only members of a clan have the right to claim land found within the clan territory. The implication is that in situations where irrigation is proposed as a food security intervention, people who live in the same administrative unit (or neighbouring areas) but belonging to other clans may be denied access to land under the customary rules. As adequately explained by informants in Amibara Woreda of Zone 3 administration, this exclusionist trend in the customary institutions may infringe upon the government’s efforts to ensure food security in the region. It also triggers conflict among different clans or territorial groups within Afar.

Besides, despite their strength in the sphere of resource and conflict management, customary institutions generally disenfranchise certain vulnerable groups and tend to be gender insensitive. They fail to protect some of the crucial rights of women. This violates the constitutional rights of women to access land and defies one of the major principles of the regional land policy.

The government tenure system comes under severe criticism owing to its biased understanding of the pastoral mode of production. The notion that depicts pastoralism as less productive and environment unfriendly has affected the mind-sets of governments in East Africa (øgard et al. 1999). The Ethiopian case is no exception. The government has, as a matter of policy, tried to be inclusive, empowering pastoralists in decision making on issues pertinent to their local conditions and indeed in other political matters as well.3 However, in reality, the government’s presence in the lowland peripheries is generally limited. The formal institutions required for the implementation of appropriate land tenure, land administration and land resources management are far from strong. Where the formal land governance structures existed, they often contravened the age-old customary institutions of natural resource management by introducing practices that were alien to community norms. Instead of supporting and providing adequate operational space to the already effective indigenous institutions, the formal machineries tend to disenfranchise and replace community-based structures. This has led to tremendous loss of land resources in recent decades. An old man in Gewane complained, ‘Now that we are side-lined, we sit back and watch as our resources are degraded and the trees are cut down and taken away by day-time robbers’ (Key-informant interview conducted on 26 August 2013).

Land use dynamics and governance: Local views and practices

During the time of the Emperors and earlier, the Afar relied on ‘nomadic’ pastoralism in which multi-species livestock husbandry formed the crux of their livelihood. Afar pastoralism is founded on the philosophy of individual ownership of livestock in communal land, which enabled pastoralists to move freely in the different ecological sub-zones. Seasonal mobility guaranteed optimum use of temporally and spatially variable resources.

In times of drought, there are often consultations between neighbouring clans on joint pastoral land use which also entails harmonisation of customary rules on natural resource use to accommodate the interests of multiple resource users. Many neighbouring sedentary agriculturalists, however, often perceived the communal pastoral land as ‘no-man’s land’ since communal land use right is often confused with open access to resources. A highland farmer who came down to Ab’ala market in Afar commented, ‘Lowland resource is like holy water, free for everyone to use at will. You can just help yourself to it at your convenient time‘.4 These attitudes have contributed to deforestation and misuse of resources in the pastoral areas. Many of the indigenous tree species have been destroyed on a massive scale for charcoal and firewood production by highlanders (Focus Group Discussions conducted in zones 2, 3 and 4 of Afar region, 24 August to 7 September 2013).

Recently, the land use pattern in the study area has exhibited a significant change owing to ecological and demographic factors as well as a shift in state policy. The frequency of drought has increased over the past few decades, compelling the Afar to look for alternative livelihood strategies including trade, wage labour migration and crop cultivation. Moreover, the Afar people have also experienced population pressure, expansion from neighbouring cultivators and pastoralists (such as the Issa Somali) and invasive weeds such as Prosopis juliflora, locally called Woyane or Dergihara.5

The Ausaareas (particularly in the Asayta and Afambo districts) have better experience in farming. Traditionally land has been allocated by customary land administrators, based on orders from the sultan via clan leaders (Kedo-aba). The apportionment of river water among users follows a similar trajectory. Traditional land administrators make reports on problems and achievements through the same structure. In parts of southern Afar, agriculture as a mode of livelihood is a relatively recent development dating back to the 1970s. However, informants in the northern part of the Afar region argued that they started farming as early as the 1960s albeit much of it was based on share cropping with highlanders. Still in other areas around the Middle Awash Valley (such as Amibara, Gewane, Chifra) informants indicated that they started crop cultivation only after the 1990s with the coming to power of the incumbent government and the subsequent pressure from the political administration. Whenever agreements with the regional government were reached on the allocation of agricultural land for cultivation, emphasis was often placed on the need to respect already existing clan-based boundaries in order to avoid conflict and inter-clan feuds (Interview with local elders in Amibara and Gewane districts, 25-27 August 2013).

In some areas, especially along the Awash River, a good deal of land has also been assigned to investors on the basis of a contractual agreement with clan heads. As part of the agreement, investors share about 30-40 per cent of their produce with clan chiefs (kedo Aba) who in turn are expected to distribute the proceeds to member households. Clan heads, for their part, are expected to take care of the agricultural fields by preventing animal and human encroachments into the farms.

Despite such changes, local people still perceive pastoralism as the most viable mode of production in the arid and semi-arid areas that characterise their environment. The increased inclination to agriculture is generally the result of the pastoralists’ frantic efforts to deal with the challenges of persistent drought and resource depletion. The inclination has also resulted from the government’s subsequent campaigns to convince herders to become sedentary farmers. Regardless of such ecological and political pressures, restocking and returning to the old ‘purely’ pastoral mode of life have always constituted the priority concern of communities. Speaking of the relative advantage of pastoralism over agriculture, a well-known community leader stated:

‘We live in an environment where the pattern of rainfall is irregular and unpredictable. In drier seasons, we move with our animals in search of grass and water elsewhere. If we were to depend on crop cultivation for our livelihood, we would be in trouble because we cannot possibly move the land to where there is adequate water when the rains fail in our place’ (Interview with clan elders in Amibara district, 24 August 2013).

The romantic connection to traditional pastoralism and the values associated with it are still solidly grounded despite gradual fragmentation of the traditional institutions over the last few decades. With the diffusion of Western value systems, urbanisation and the expansion of technological gadgets (such as modern communication and transportation facilities), the younger generation has become reluctant to sustain local culture. They consider traditional institutions as archaic and primitive and call for radical change in the socio-cultural set-up. As a result generational conflict has become evident. An informant in Assayta district described the steady loss of tradition as follows:

The power of the sultan which had political and judicial functions is now being diluted. The clan leaders which were the main actors in reconciliation are made powerless too; and they are now replaced by the modern courts. Even the camel, our most cherished animal, has been replaced with motor vehicles; and there are modern drugs instead of our traditional medicine. We don’t know where we are heading (Key informant interview in Assayta district, 5 September 2013).

Clan leaders still command respect but traditional administration of pastoral land is based on consensus building involving ordinary clan members including women. The perception (by non-Afar) that supreme power is vested in clan leaders is no longer correct. Decisions on how pastoral land should be used and administered, including the delineation of boundaries and assignment of land for grazing and settlement purposes, are made collectively. This is not to undermine the role played by clan heads in leadership, nor to deny their active roles in gauging the behaviour of clan members, but to underline the fact that clan headship is not hereditary and hence clan leaders do not possess veto rights on community matters.6

The focus group discussions conducted in all the study sites revealed that little has changed over the past several decades regarding local people’s perceptions and views on how land should be administered. Land and water resources are largely considered God’s gifts and in principle all people have the right to use them. Local pastoralists believe land belongs to the specific clans. This is a traditional view that descended down across generations since time immemorial. In connection with this, a key informant in Assayta district stated: ‘We [the Afar] don’t joke about four assets: religion, women, land and livestock’ (Interview with Afar elders in Gewane district, 25 August 2013).

Similarly, informants in the Amibara district supported this view through their proverbs about a malignant fear of an uncertain future if their communal tenure system is derailed. One proverb from the northern part of the Afar region states, ‘Ada-Habiniki-Adewi-konegera‘ literally translated as: ‘Once you lose your original trail of tradition, the enemy takes advantage of your resources’.

Community members are generally of the view that clans should be further empowered to deal with land use, administration and management. They believe that land is an indispensable asset of the Afar and that no land is free to be used for any other purpose than livestock husbandry. Clan-based tenure has always demonstrated its strength and the role of the formal administrative units (such as Woreda and Kebelle7 administration, agricultural and pastoral development offices) has been limited to the provision of technical backstopping to facilitate pastoral/agro-pastoral development. According to informants, the formal structures are almost entirely engulfed by the customary institutions. In its present state, the administration finds it useful to soothe community interests to some extent and does not often use vehement force to bring about radical changes to the status quo with regard to land administration matters.

On issues of resource governance, land administration and conflict management, what local people perceived as an appropriate role for government institutions is supervision and the provision of consistent technical and financial support to customary institutions. This could be done though training, assignment of incentives/remuneration for individuals or groups taking care of resources in the clan-based structures, experience sharing, and provision of logistical support. Government authorities were also advised to continue encouraging restorative justice by channelling disputes into appropriate local structures and assisting elders in enforcing sanctions when deemed necessary. In relation to this, the pastoral Afar often say ‘God and the state should rule from above‘.

As poverty was perceived to be a proximate factor in conflict, elders also advised the government to proceed with its infrastructure development (schools, roads, clinics, expansion of pastoral and agro-pastoral extension systems, telecommunication and communication facilities) in order to facilitate inter-cultural contact and dialogue among various groups.

Generally the following conditions currently play an inhibiting role on proper land administration and judicious management of range land resources in the Afar region.

First and foremost, there is a lack of participatory bottom-up approaches in policy planning and implementation: people often complain about blueprint approaches that usually descend down to the villages from either the federal or the regional government without prior consultations with local communities. There have been problems with consensus building because of the lack of commitment by those responsible to influence change. Often, there is a communication gap and misunderstanding leading to disparity between government plans and intentions and local people’s perceptions and knowledge of policies, programmes and strategies. Government authorities not only lack the capacity to impact change in the minds and hearts of pastoral people, they also lack the determination and stamina to challenge traditional pastoral values because of stiff resistance from communities.

Secondly, the functional integration between various interventions is very weak. Different programmes facilitating the move towards sedentary agriculture and the subsequent change in land administration lack proper coordination and integration. There is also lack of adequate government financial support for alternative livelihood and income generation in the lowlands. Some Afar informants asserted that communities may consider dropping the traditional pastoral philosophy on land administration only in the presence of a well demonstrated viable alternative to pastoralism which they find difficult to discern presently.

Furthermore, mapping of land resources is not well developed in Afar. This puts appropriate land use planning at risk. Currently little is known about the potential for agriculture and the areas identified for settlements have not been selected in concurrence with local people’s needs and priorities.

Policy and legal framework

As Helland (2006:9) states, government interest in the lowlands was observed during the imperial regime as early as the 1950s due to the high irrigation potential of the land. The 1955 Constitution of Ethiopia stated that ‘all property not held and possessed in the name of any person, natural or judicial, including … all grazing lands… are State Domain’ (Helland 2006). Although the feudal tenure system was abolished, the 1975 land reform retained the sole constitutional right of the State to own rural land. For the first time in modern history, Ethiopian farmers enjoyed land use rights enabling them to be the masters of their own produce. According to current rural land laws, communities are granted not only usufruct rights but also the right to inherit, transfer and lease land. However, sale of land is prohibited by law. All rural land (whether agricultural or pastoral) belongs to the state. Generally, the pastoral areas have until recently remained largely unaddressed in national land policies, laws and proclamations. In fact, the notion of ‘land’ has been predominantly discussed in the context of the agrarian mode of production.

The federal rural land administration and land use proclamation ratified in 2005 (Proclamation 456/2005) grants regional governments the mandate to draft their own detailed land administration laws, proclamations and guidelines that are suitable to local contexts in the respective regions. The Afar region was among the first to initiate a policy of pastoral land use and land administration in 2008. This was followed by the ratification of Proclamation 49/2009, along with specific regulations and guidelines for implementation that were issued in 2011. However, the new land use policies were not supported by appropriate governing institutions for efficient utilisation and management of resources, which led to deforestation and land mismanagement.

With regard to land tenure policies, people felt that the different regional states in federal Ethiopia should have been treated differently as they are historically and culturally different. Others believed traditional and statutory tenure systems can be harmonised to become mutually supportive. The biggest problem for them was the marginalisation of communities in land administration discourses.

A prominent key informant in Ewa district said the following:

The government wants to bring change to our tenure system which we may welcome if convincing, but how is this possible if we are not consulted in the decision-making process? Some administrators say our times [the rule of traditional people] are gone but they rush back to us whenever there are resource-based conflicts across the region (Interview with a clan leader, Amibara district, 23 August 2013).8

According to informants, the Afar are ready to make concessions in a way that will accommodate major government concerns and demands on condition that local institutions are recognised and the noble mandate of administering land is given to the traditional system. Pastoralists tend to be particularly uncomfortable with the idea of destocking because livestock are the most indispensable assets with economic, social and cultural value. In connection with this, one of the key informants stated: ‘They (government officials) asked us to reduce the number of our animals; in response, we asked them to reduce the amount of money they have in the bank first‘. Livestock are a source of insurance for the Afar. Animal husbandry is not only a source of income but also the foundation upon which social prestige and honour are based.

Villagisation and resettlement programmes

Two major government activities have curtailed pastoralist mobility in the middle and lower Awash Valley of the Afar region: villagisation and resettlement. Both significantly affect pastoral tenure and resource governance.

According to government authorities, voluntary settlements of pastoral communities are being initiated in order to supply people with basic infrastructure such as potable water, schools and health services, and agricultural inputs. The ultimate goal is to reduce their vulnerability to climate change impacts. Pastoralists are advised to combine quality-based animal husbandry with irrigation-dependent crop cultivation to ensure household food security (Focus group discussion with government officials in Amibara and Gewane districts, 24 and 26 August 2013). Successive governments in Ethiopia believed the sentimental attachments of pastoralists to their cattle should be replaced with a new, ‘modern’ attitude that curbs mobility. In ordinary discourses officials usually maintained the view that ‘pastoralists need not always follow the tails of their cattle to earn livelihoods‘. The formal land use and land administration policies were therefore intended to guide pastoral settlements, land distribution and certification activities. In principle, the regional government recognises the customary rights of pastoralists to grazing land. Nevertheless, on the ground, more work is being done to encourage pastoralists to lead what is often termed as ‘undisturbed life’.

Local administrators believe that change of community attitudes has been successfully achieved through awareness campaigns. As pointed out earlier in this paper, the more progressive younger generations and those in government administration think there is a need for drastic change in the pastoral way of life including the traditional land use and land administration trajectory: a total shift from the pastoral communal mode to one of predominantly government-owned, equitably distributed, cultivable land. They argue that pastoralism is no longer resilient given the ecological problems, loss of livestock, population growth and other pressures. Therefore they feel it is high time to distribute communal land to individual households for agricultural purposes based on the experience in the highlands (Interviews in Ab’ala, Kuneba and Ewa districts, September 2013).

Consequently, the government redistributed land which was previously occupied by investors. Those who voluntarily settled were provided with a hectare of land per household to start with. These government-sponsored pastoralist settlement programmes have taken root in several areas of the Lower and Middle Awash Valleys of the Afar region. Up to 20% of the land previously assigned to investors has been reclaimed for this purpose.9 The programme is currently being implemented in 9 districts, viz., Afambo (seven centres), Assayta (eleven centres), Dubti (eleven centres), Gewane (five centres), Amibara (five centres), Awash (one centre), Ewa (eight centres), Mille (four centres), and Burmodayto (four centres). According to the information obtained from the administration, the specific settlement centres were selected on the basis of some criteria such as proximity to perennial rivers, ground water potential, and proneness to flood risks, to mention just a few. Key opinion leaders were approached to convince people about the importance of villagisation. Some clan leaders were also instrumental in the diffusion of regional land laws and identification of beneficiaries to promote fair and equitable distribution of land resources. Efforts were made to ensure that such a scheme was acceptable by all or the majority of the people (Interview with Woreda officials in Dubti district, 30 August 2013).

There were, however, some challenges. Informants argued that the modality and conditions for such programmes often lacked clarity and have not been properly communicated to rural communities in advance. The principles and modes of action as well as intended target outcomes generally remained vague or obscure to the local population. These packages often came down to the region from the federal level policy makers in the form of orders. The lack of adequate grassroots participation has been reported as government authorities exhibited excessive dependence on clan leaders during consultations. The government has recently adopted a strategy of co-opting clan leaders10 into the formal government administrative structures in order to communicate its policy, facilitate easy diffusion of its plans, and ensure speedy implementation. Those who occupy key positions in the regional administration also tend to be sons and daughters of the clan leaders with divided loyalties to government interests on one hand and the demands of local community members on the other hand. The villagisation scheme also lacked consistent follow up and monitoring. It was highly centralised with very weak institutional linkages at various levels of decision making. Informants argued that it is a mirage (Bekerbeker) to try to improve pastoralist living conditions through sedentarisation. One of the clan leaders interviewed during the study elucidated the situation as follows:

The idea of pastoralist settlement with all the social and economic requirements met to our satisfaction is like driving in the desert. From a distance, you perceive as if there is a lake in the middle of the road and as you go closer the lake goes farther and farther away until you finally realize that it was only an illusion (Interview with clan leaders in Gewane district, 25 August 2013).

In general, the pastoralist Afar have always considered crop cultivation inferior to pastoralism. An informant in Amibara district, for example, enquired:

‘Why does the government want us to settle and start agriculture while everybody knows that our neighbouring cultivators are much poorer than us? They are the ones who always depended on food aid for survival’.

Pastoralist resettlement schemes of the government also posed another challenge to traditional pastoral mobility in southern Afar. Article 40 of the 1994 Ethiopian constitution states: ‘Ethiopian pastoralists have the right not to be displaced from their own lands. The implementation shall be specified by law’. Subsequent land appropriation and compensation laws granted pastoralists the right to obtain compensation for pastoral land appropriated by government for development projects such as sugar cane investments (although valuation of pastoral communal land has never been easy). Compensation for resettled communities11 is paid in the form of cash, provision of alternative farm lands as well as improved access to basic services. Regrettably, promises were often broken in some areas and expectations surpassed actual achievements on the ground. The proposed socio-economic support (schools, potable water supply, and clinics, to mention a few) were not largely fulfilled to the satisfaction of local communities.

Informants argued that settlement/resettlement plans were not well thought through before implementation. The areas identified for permanent relocation were not carefully selected and were found to be unsustainable due to increased proneness to more environmental risks such as drought, floods, excessive heat and human and animal disease. Clan leaders complained about double standards as they also lost benefits from informal land deals with investors in their place of origin besides the lack of appropriate infrastructure at resettlement destinations.

Tenure changes and conflict

In many instances, communal access to resources in the Afar gave way to private ownership, land grabbing and the replacement of customary tenure with modern systems. However, changes in the land use and land tenure were not accompanied by appropriate and implementable policies and laws. Besides, the institutional structures that safeguard property rights and good governance remained weak. Even the regional policies and laws that were established in recent years have remained too theoretical. These ‘tenure gaps’ created a breeding ground for disputes between local communities and the state.

Tenure conflict between the formal and informal systems dates back to as early as the 1950s and 1960s when irrigation schemes along major rivers challenged the communal, pastoral land use system. During the subsequent years, the government’s interest in the lowlands increased and more and more land use forms were introduced (e.g. in the form of national parks, sugar cane and cotton farming). During those early years, the traditional pastoral tenure did not easily succumb to the new situation owing to the relatively better social, economic and ecological conditions. At present, the pastoralist Afar tend to be confused with an overlap of two rather fragile land tenure systems. The traditional pastoral system is eroding; but the formal laws on land use and land administration have not been strong enough either. In a situation where neither is working effectively land resource management is put at stake. Weak land administration leads to competitive interests among stakeholders that are causing massive shrinkage of land resources in Afar. The Afar have lost a large amount of land due to expansion from neighbouring highland cultivators and Issa Somali pastoralists; expansion of commercial agriculture by local investors; development projects run by the state, as well as the spread of invasive trees. These developments create frustrations among Afar pastoralists and ultimately lead to conflict among various resource users both within and outside the Afar territory. A change in tenure from communal land use to a more private cultivation-based practice further complicated these conflicts since the new tenure automatically excluded other users who have had secondary access rights over grazing land. With the advent of the new ethnic federalism in Ethiopia, resource-based conflicts have since been compounded with the quest for political supremacy and issues of territoriality raised by various ethnic groups.12 The Afar people who remained largely fragmented and divided along clan structures in the past now perceive themselves as a unified political unit enabling them to defend their land collectively. However, it must also be noted that when resource-based conflicts between various communities erupt, the customary institutions are called in to amicably settle the disputes and subsequently resolve violent conflicts. Elders that are perceived as wise, impartial and honest act as mediators. They conduct a series of dispute-processing gatherings until negotiated settlements are finally reached in line with the culture of forgiveness, transfer of compensations and respect for traditional law. In as much as customary institutions put heavy emphasis on sustainable peacebuilding through restoration of community relations, they are much more effective than the government judiciary structures whose main role is to serve justice through formal litigation based on a fixed code of law. The informal system, on the other hand, is more flexible, transparent and participatory because it is based on local traditions, shared norms and value systems that are well known to community members since time immemorial.

The federal arrangement no doubt brought socio-economic transformation, the right to self-administration and relative political stability in the region. This is widely seen as a positive sign in the wake of a history of confrontation between Afar pastoralists and the previous repressive regimes who invaded their land. Afar informants acknowledge that state-community relations have generally improved following federalism. An Afar informant in the Middle Awash Valley said:

In the previous regimes who pursued a totalitarian political rule, we fought against our largely non-Afar administers and waged war against the national army who sometimes used helicopter gunships to attack us. Now, we don’t dare to kill our blood and flesh as the administrators are our sons and cousins (Interview with clan elders in Gewane district, 25 August 2013).

However, these developments by no means reduce the significance of incidents of clan-based violence and aggressive moves against local authorities over issues pertinent to land use and land administration. Disputes are still prevalent in the region because the rights of pastoralists are vague with regard to resource use and access under the government tenure system. As long as the state dictates various land use forms in the pastoral areas using a top-down approach, pastoralists feel the spasm of tenure insecurity that often leads to conflict.

Another outcome of the tenure gap concerns relations between state and private investors. State-investor relations were generally marred by feelings of mistrust and suspicion. For example, government officials often accuse investors of spreading rumours about government intentions to confiscate pastoral land for some other purposes while harbouring the ulterior motive of triggering local resistance.13 The investors in turn blame the regional government for being inefficient and inconsistent with its land administration plans. It is not at all uncommon to witness contradictory pastoral development schemes. For example, in 2013, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture initiated a five-year USAID-supported14 project called Land Administration to Nurture Development (LAND) which among other things focuses on protecting the rights of pastoralists to communal land. The overall objective was to improve tenure security of pastoralists through land registration and certification. While this was welcomed by a great majority of traditional pastoralists, it was not clear how such a programme would be synchronised with other seemingly contradictory government packages, such as the establishment of sedentary agriculture-based economy in the pastoral areas.

Conclusion

Land is still the basis of livelihood for the Afar pastoralists no matter how scarce it has become at present. Apart from the ecological and demographic factors, the widespread depletion of land resources may also be attributed to problems of land use and land administration as well as conflicting tenure systems.

It appears that relations between the formal and informal tenure systems are characterised by a state of tension and conflict with far-reaching political impacts. Land tenure transitions have increased the vulnerability of pastoralists as more and more of their grazing land is grabbed by other stakeholders. Moreover, traditional pastoralism is challenged by other land use forms. The dominance of the agrarian economy, the privatised form of land ownership, and encroachments by third parties have curtailed pastoralist access to grazing land and water. This has resulted in tenure insecurity that has ultimately culminated in poverty and destitution.

The way forward is one that recognises the traditional structures and promotes their integration with formal tenure systems. This may take two forms: incorporating the indigenous system into government laws and policies, or allowing both tenure systems to operate side by side. When operating in parallel, each institution (formal or informal) should assume a clear mandate, role and responsibility on issues related to natural resource governance, land use and administration, and conflict management. The customary institutions should be empowered to take a leading role in managing land and resolving conflicts based on local norms and value systems. Awareness campaigns could then be organised by the government on issues related to equitability and fair distribution of resources, gender issues and inclusive decision making to mention just a few. As pastoralist systems have unique features distinct from that of agrarian based economies, there is a need to institute context-based approaches of land tenure and land administration that take into account differences in economic, socio-cultural and political context.

Sources

- Central Statistical Authority 2008. Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia: Population size by age and sex. Addis Ababa, Population Census Commission.

- Cotula, Lorenzo, Camilla Toulmin and Ced Hesse 2004. Land tenure and administration in Africa: Lessons of experience and emerging issues. London, International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED).

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2005. Rural land administration and land use proclamation No 456/2005. Addis Ababa, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

- Galaty, John 2011. The modern motility of pastoral land rights: Tenure transitions and land-grabbing in East Africa. Paper presented at the international conference on global land grabbing, 6-8 April 2011, at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Sussex.

- Getachew, Kassa 2001. Tradition, continuity and socio-economic change among the pastoral Afar in Ethiopia. Utrecht, International Books.

- Guinand, Yves 2000 Afar pastoralists face consequences of poor rains. UNDP-UEU. Available from: <http://search.yahoo.com/search?p=Afar++Pastoralists+Face+Consequences+of+Drought&sm=Yahoo%21+Search&fr=FP-tab-web-t&toggle=1&ei=UTF-8> [Accessed 15 September 2013].

- Hassan, Ali 2008. Vulnerability to drought risk and famine: Local responses and external interventions among the Afar of Ethiopia. A study on the Aghini pastoral community. Available from: <http://www.google.co.za/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CDkQFjAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fopus4.kobv.de%2Fopus4-ubbayreuth%2Ffiles%2F364%2FAli_Hassen_web_low_version.pdf&ei=pmE_VMKaO-He7AbKtIH4Bw&usg=AFQjCNHwDJxd8v0w7Eo6WPI0kUVrMUdKdw&bvm=bv.77648437,d.d2s> [Accessed 16 March 2014].

- Helland, Johan 2006. Pastoral land tenure in Ethiopia. Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen, Norway. Available from: <https://www.mpl.ird.fr/colloque_foncier/Communications/PDF/Helland.pdf> [Accessed 12 March 2014].

- Markakis, John 2004. Ensuring the sustainability of pastoralism in East Africa. Minority Rights Group (MRG). Available from: <http://www.minorityrights.org/admin/Download/Pdf/MRG-PastorialistsRpt.pdf> [Accessed 21 March 2014]

- øgard, Ragnar, Trond Vedeld and Jens Aune 1999. Good practices in drylands management. Noragric Agricultural University of Norway, As, Norway.

- Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia 2010. Pastoralism and land: Land tenure, administration and use in pastoral areas of Ethiopia. International Institute of Rural Reconstruction, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Piguet, Francis 2002. Afar region: A deeper crisis looms. Assessment Mission: 10-19 October 2002. United Nations Development Programme Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2000. Afar pastoralists face consequences of poor rains. Rapid Assessment Mission: 19–24 April 2000. United Nations Development Programme Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia.

Notes

- Woreda is an administrative unit below the region and zone structures. For the sake of convenience the term ‘district’ has also been used in this paper to denote the same political unit.

- The sultanate is a hereditary spiritual leadership structure. Sultan Ali Mirah and his son Hamfrey Ali Mirah are considered the most influential spiritual leaders among the Afar especially in the Ausa area of Zone 1 administration.

- There are groups that reflect pastoralists’ concerns at higher levels of decision making. For example, the Pastoral Affairs Standing Committee addresses the demands, interests and priorities of Ethiopian pastoralists and brings them to the attention of policy makers in the parliament.

- Informant perspectives quoted throughout the paper are the author’s own translations from Amharic or Tigrigna languages which the Afar people speak reasonably well.

- Named after the dominant political parties of the last two governments in Ethiopia.

- In fact, informants have made it clear during the discussions that clan leaders may be replaced by others if they misbehave or act against the interest of the community.

- Kebelle is the smallest administrative unit in the government administrative structure. The organisation of Woredas and Kebelles in Afar do not necessarily follow traditional grazing systems.

- The Afar people have traditional conflict resolution mechanisms that are effective. Experience has shown that conflict cases that were handled by the formal courts have ended up without a satisfactory solution. Hence, the local administration now encourages resolution of disputes by local elders using customary approaches.

- During the Derg regime, large tracts of pastoral land around the Awash River were taken by state farms, much of which was returned to the community after the EPRDF came to power. Instead of developing the land themselves, clan leaders then decided to rent out the land to investors on behalf of the community for a 30-40% profit share.

- In many of the districts we visited, clan leaders or their close associates assumed important government positions either as administrators or as counsellors, but they often find themselves in difficult positions reconciling state trajectories and pastoralist interests (which they themselves inherently hold as traditional leaders).

- Government-run large scale development projects (such as the Tendaho sugar cane project) have displaced pastoralists from their dry season grazing land near the Awash river (the biggest perennial river in the Afar region).

- Prior to the 1994 constitution which gave ethnic groups their own regional administration, the Afar were part of different provincial administrations which currently fall under the Tigray, Amhara and Oromia regional states.

- There were occasions where investors made land deals directly with clan heads without prior permission and clearance from the government, which often resulted in land administration problems.

- United States Agency for International Development.