Abstract

The use of transitional agreements to resolve differences between the state and non-state armed actors across the African continent appears to be on the rise. However, many of these transitional agreements tend to be stagnant and fail to deal with grievances, causes of political unrest and conflict or to provide sustainable paths to democracy. Drawing on the civilian-led Transitional Government of Sudan from 11 April 2019 to 25 October 2021 (the length of the transitional agreement), and an original dataset, this article argues that the policies of the transitional government of Sudan, political rhetoric and the challenges of implementing transitional agreement policies did not align with political realities. This was primarily due to the inability of the Transitional Government of Sudan to dismantle existing power structures under previous regimes. We find that the Transitional Government of Sudan neglected to consider path dependencies of the previous regimes, which led to its being unable to provide the people of Sudan with strategies that could help to circumvent existing structures set up by past regimes. As a result, the efforts of the Transitional Government of Sudan acted as exacerbators of existing inner struggles. The article argues for the need for better technical support and provisions to support incoming transitional governments trying to emerge from autocracy or dictatorship to democracy during transitional periods.

Keywords: Sudan, transitional government, regime security, military and state power.

Introduction

In July 2019, critical stakeholders in Sudan, including the Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) — a coalition of political organisations and professional associations — brokered an uneasy power-sharing arrangement designed to steer the country through a 39-month-long transitional period before ceding control to an elected government. Under the provisions outlined in the agreement and subsequent constitutional declaration, a series of proposals was launched to help support and safeguard this reform process and mitigate any resurgence of illiberal or dictatorial norms. During the signing of the agreement in 2019, efforts on behalf of the Transitional Government of Sudan (TGS), civil society organisations, rebel groups and international partners were underway. However, on 25 October 2021, Sudan succumbed to yet another coup after a failed attempt on 21 September 2021, which led to the dissolving of parliament and the declaration of a state of emergency (Tchie and Mashamoun, 2022). Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok was arrested and Lt. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sovereign Council, framed the coup as an attempt to push Sudan towards stability and progress. Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok was later reinstated as head of the TGS as part of a 14-point agreement — only to step down weeks later. Meanwhile, civil society groups and protesters rejected the move and continued to seek a civilian-only government (Duursma, 2020). Pressure from the international community, shuttle diplomacy from the then United Natinos Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan and the African Union (AU) led to the release of detained officials and the reinstatement of the civilian-led authority, but in April 2023 Sudan fell into a deep crisis of conflict that spread to many parts of the country.

While African mediation efforts have produced some noticeable outcomes (Duursma, 2020), such as reaching an agreement, their success may not necessarily be identical to creating long-term stability. In fact, recent transitional agreements (TAs) such as the one in Sudan were stagnant, failed to deal with the root causes of grievances (they neglected the challenges that transitional governments must navigate) and often appeared to have delayed steps towards democratic consolidation (Richmond, 2013). Despite this, there has also been a growth in the use of TAs as conduits to stability, which for many civilians in Sudan leaves them assuming that these agreements will produce the necessary and desired outcomes (Tchie, 2023). In fact, previous research has found that TAs produce forms of military governments led by military actors who entrench authoritarian rule and use the TAs to eventually deliver electoral authoritarianism (Schedler, 2007). This raises three broader lines of inquiry that existing literature has failed to address. First, how successful are transitional power-sharing agreements led by transitional governments with fragile structures, which is not necessarily identical to long-term stability. Second, whether the materialisation of TAs between the military and civilians, masked as civilian-led or as joint civil‒military transitions, are effectively meeting their agenda of civil‒military relations. Finally, whether recent TAs — often triggered by popular civilian uprisings — are working. Thus, this gap provides us with an opportunity to understand the use of transitional governments in Africa by drawing on the case of Sudan. Sudan was selected as a single case study to allow the examination of complex institutional phenomena from multiple perspectives over time. In selecting Sudan, the article provides an understanding of the context which enables the authors to leverage exclusive access to phenomena that may be challenging for external parties to observe. Thus, the article assesses the power structures in place in Sudan to understand the complex environment in which the Sudanese transitional government had to navigate to deliver on the TA (which lasted from 2019‒2021).The article also explores how the TGS implemented provisions within the TA and whether it acted as an exacerbator of existing inner struggles.

The article is structured in three parts. Section two examines the formation and structuring of state power in Sudan. This section analyses how Sudan has been organised since independence and how past state authorities and regime(s) have restructured state power using security forces. It explores the 2019 civilian uprising in Sudan and the regime’s fall. Section three outlines the research design used to collect data as part of the analysis, touching on the methodology, coding processes and data limitations. The section then evaluates the efforts of the TGS to achieve the provisions of its Constitutional Declaration and examines the efforts of the TGS policies. The results reveal that while there was some effort by the TGS, structural challenges related to how the state and power were institutionalised, organised and distributed in Sudan under past military regimes restricted the TGS from operating within and outside the existing state system. Thus, to some degree it has acted as an exacerbator of existing inner struggles. The final section provides concluding thoughts designed to address the questions proposed above.

Structuring state power

Sudan’s history has been marked by several transitions that have set the country on a course from militarised autocracy to civilian democracy, from multiple regional conflicts to flawed peace deals and, crucially, from Sudan as an exiled state to one that once attracted vast international support. Despite being one of Africa’s first states to gain independence from colonial rulers, the mechanisms governing state power before independence have continued to undermine the post-colonial arrangements, despite shifts of state control between civilians and the military. This has resulted in Sudan’s conflicts having their roots in the colonisation period (Johnson, 2011), which witnessed a north‒south divide fuelled by Turkish and British imperialists who favoured resource extraction through economic and social strategies. Many of these strategies focused on investment in northern Sudan and extraction from the South, between 1920 and 1947 (Ali et al., 2005). Through this north‒south divide by colonial powers, further structural divisions were created by northern elites, which led to the first Sudanese civil war between 1955 and 1972. This was later resolved under the Addis Ababa Agreement (Beswick, 1991: 200). The divide created an inter-group and inter-regional relationship that led to peripheral grievances during the preparation for independence. The reason for this was that the northern elites exclusively inherited vast political control over the country (Deng, 1995: 488).

Through brutal military repression and strategies of division, “identity”, co-opt and rule (Mamdani, 2009), the British colonial administration in Sudan was able to maintain sustained rule. The strategy was not new across the African colonies, but this fundamentally set African states back decades, hindering their transition to unique forms of African ecological democracies. Consequently, current African democratisation efforts have their roots in the institutional legacy of colonial domination linked with indirect rule and every day running of the “native authority system” (Mamdani, 2009: 192). Embedded in this strategy was the successful attempt to create a narrative that vilified pre-colonial Africa as barbarous and uncivilised. Underscoring this structure was a process of glossing over the violence of colonial occupation, the assertion of civilising missions based on the unquestioned moral and material superiority of western civilisation, and the justification of colonial rule as a form of trusteeship. This notion has evolved and continues to fashion state structures through liberal peacebuilding and democracy ideologies and frameworks of liberal democratisation in Africa. It also manifests through support for TAs, western development aid and current security approaches (McAuliffe, 2017). This has created a wave of governance and leadership incompetency that has restricted Africa’s steps towards unique forms of democracy (Jonathan et al., 2020).

In post-independent Sudan, colonial structures were expressed through post-colonial regimes that remastered colonial policies. These regimes mirrored tactics and techniques through divide-and-rule campaigns and exploitation of peripheral territorial control. Such tactics would later shape conflicts outside of Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, and would feed into the strategies used by the Sudanese state to gain control or intervene to take complete control of the state (El-Battahani, 2006). Inevitably, this laid the groundwork for the post-colonial class formation and the rise of the northern bourgeoisie who dominated the Sudanese political arena and added a class dimension to the developmental state (Khalid, 1990:72‒73). This post-independence class domination manifested itself through a Nile Valley elite dominance of the political system. To date, not one of Sudan’s heads of state is ethnically linked with states outside of Khartoum (riverine tribes), which demonstrates a profound lack of diversity and inclusion. Khartoum-centred policies led to internal conflicts often interlinked with land and natural resources disputes. This was further aggravated by the erosion of governance, weak institutional and law enforcement arrangements and poorly implemented policies. For example, traditional leaders previously played a significant role in natural resources challenges, conflict management systems and local governance structures across remote areas, but many of these systems have been dismantled. Most of the policies implemented by the military regimes of President Jaafar Nimeiry and President Omar al-Bashir still contributed to the erosion of state and local capacity (ElHadary and Abdelatti, 2016).

Political and economic exploitation

Over 50 years, Gaafar al-Nimeiri (1969–1985), the National Islamic Front (1989–2001), Omar al-Bashir (2001‒2019) and the transitional government (2019‒2021) revived old colonial policies and arrangements that would help restructure state power to the advantage of security forces and elites. This allowed them to abuse resources outside of Khartoum for personal gain (ElHadary and Abdelatti, 2016). During the early 1970s, Nimeiri deployed ‘infitah’ economic liberalisation policies, opening the pathway for Arab Gulf states and further resource extraction policies. The nationalisation and sale of land for mechanised agriculture, introduced in the 1970s, 1990s and 2013, favoured investors from Khartoum or outside of Sudan at the expense of local communities. This further exasperated tensions between the centre and the peripheries (Tchie, 2021). These policies produced capital-intensive and large-scale agricultural schemes that focused on exporting raw materials to ‘catch up’ economically (ElNur, 2008).

In 1989, Bashir’s Islamist-backed coup further weakened civil society and reorganised state power to create a patronage network, particularly among large parts of the security sector. This placed Sudan’s politics, economy and resources into the hands of the security forces and elites from Khartoum who were masked as Islamists and associated with the National Congress Party (NCP) (Tchie and Ali, 2021). As a result, security forces such as the Rapid Support Force (RSF) and segments of the Sudanese Army controlled gold mining areas (Ibrahim, 2015) and other natural resources, which contributed to the destruction of pastures in eastern Sudan (UNEP, 2020). Across the north‒south border regions, state exploitation policies also renewed conflicts over timber exploitation by the charcoal companies in the north that encroached on forests from southern areas (UNEP, 2020).

Institutionalising power through security actors and conflict

Under Bashir, security forces were used as critical instruments for political power and in the interests of those associated with or who were part of the NCP. The discovery of oil and its revenues enabled Bashir’s regime to dramatically increase military expenditure, expand and upgrade its military hardware, develop an arms industry and use oil infrastructure to prosecute war (Human Rights Watch, 2004). Bashir’s control over state power also included using political Islam to exploit power between competing factions within the regime and infiltrating officials. Across the security sector, Bashir — with support from the NCP — created and supported paramilitary and local forces, incentivising them through the purchase of uniforms and regular salaries. The strategy also included embedding armed forces or the intelligence services under the command and control of the president’s office to directly restructure security sectors and state institutions.

Bashir’s regime dominated four critical components of the Sudanese state across society and the security sphere. The first component was the Sudanese Islamic Movement’s religious ideology, a crucial tool for Bashir’s regime stability that comprised competing power centres. The second component was to control the National Intelligence and Security Service, led by Major General Salah Abdallah ‘Gosh’ during the institution’s former years. Gosh played a role in the alleged attempted coup of 2012 and the April 2019 ousting of Bashir. The institution was later rebranded as the General Intelligence Services in July 2019. The third component was the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), headed by Bashir and used to reform the political economy of state power. Bashir frequently retired and purged officers from the SAF to prevent future coups and rebellions. The SAF were used in many operations against the South Sudanese Liberation Movement/Army in the pre-independent South Sudan. The final component was the RSF, composed of elements from the Janjaweed militia group, now headed by Lieutenant General Mohammed Hamdan ‘Hemedti’ Dagalo, field commander for the RSF counter-insurgency unit and deputy chair of the Sudanese Sovereign Council (Sudan Tribune, 2021a). The RSF fought against rebel groups in Darfur, the Blue Nile and South Kordofan (Stigant, 2023).

The fall of the regime

Between 2018 and 2019, inflation was rising and the Sudanese people were struck by the rising cost of everyday items such as bread and fuel. This squeezed households by dramatically increasing the cost of living. Non-violent protests soon erupted outside the capital in April 2018 and eventually called for the regime’s removal in mid-December 2018. As protests spread across the country, Bashir attempted to make concessions, but Sudanese citizens persisted with calls to remove Bashir. In April 2019, after mounting pressure internally, Sudan’s long-standing head of state, Bashir, was removed by military generals. Negotiations between the Sudanese Professional Association or opposition alliance and the Transitional Military Council (TMC), mediated by the AU and Ethiopian Prime Minister, were underway when further violence followed. The TMC persisted in maintaining dominance and the status quo, while the alliance insisted that the transitional government be civilian-led and include marginalised groups. The agreement between the TMC and the alliance went through many drafts. At first, the TMC wanted a two-year transitional period, but the opposition alliance wanted a four-year transitional period. A deadlock emerged over who would control the three branches of government: the Sovereign Council, the Executive and the Defence and Security Council. The compromise was a messy middle ground and not a practical one, given the previous governance structures in Sudan. Four months later, the TMC and FFC signed a three-year transitional power-sharing agreement.

However, during this period, Sudan’s path to democracy included attempted mutiny (BBC, 2020), attempts to kill former Prime Minister Hamdok (Al Jazeera, 2020) and a coup on 25 October that removed the prime minister and dissolved parliament and the TGS. Furthermore, a more recent outbreak of violence occurred in April 2023. This demonstrates the fragility and difficulty of consolidating peace in Sudan and the long road that lies ahead before future elections occur. In addition, it highlighted the continued power imbalance between the Sovereign Council, the Executive, the defence and security forces, civil society groups and protesters. The inexperience of the opposition and increased fragmentation of leaders within the FFC were married with huge unrealistic expectations of transforming the country’s political institutions and socio-economic structures into a fully-fledged democracy in three years.

Since Bashir’s removal, state power has continued under General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman al-Burhan, head of Sudan’s former Sovereign Council and SAF, and Lieutenant General Hemedti, head of the RSF (Tchie, 2019). Al-Burhan has taken control of the Military Industry Corporation, a SAF holding company in charge of many of the companies once owned by NCP leaders and Bashir’s associates. In contrast, the RSF controls the businesses previously run by General Intelligence Services. General Abbas Abdelaziz, former head of the RSF, oversaw al-Sati, another holding firm (Gallopin, 2020). The incapacity of the TGS to dismantle existing state structures, implement security sector reforms and solidify control over tax revenues has meant that the TGS had no control over companies run by the security actors during its tenure. This demonstrates the regime’s power that continues to hold Sudan ransom. In June 2020, the TGS stated that 638 of 650 government-owned companies do not pay income taxes to the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, including 200 belonging to the military actors (Sudan Tribune, 2021b). Consequently, the restructuring of state power under the security forces over the last 50 years has meant the TGS control over the state would have been limited and with large portions (if not all) of the state still under the old system.

Assessing Sudan’s transitional government

The following section provides details of the research design and method applied to the data collected to analyse the efforts and progress of the policies of the TGS and their overall achievements. This is done by evaluating the policies and steps taken by the TGS to achieve its mandate within the provisions of the Constitutional Declaration signed by the FFC and TMC on 18 August 2019 until the coup on 25 October 2021. Using qualitative data, the analysis draws on an array of data sources, including local news, newspapers, online reports, government sources, websites, policy documents and civil society reports. The analysis captures a snapshot of two years of data, collected over three years and continually tabulated against the provisions within the 2019 Constitutional Declaration. The data collection included policies aimed at reaching provisions within the Constitutional Declaration and data were gathered from online newspaper outlets but scrutinised against other sources to confirm or dismiss the claims. Newspapers such as the Sudan Tribune and Radio Dabanga provide a consistent stream of information on the TGS and were consulted daily as part of the data collection and data review points. Both papers publish in Arabic and English, which allowed for variations in reporting to be detected and verified.

Data collected daily were also reviewed weekly, while announcements on policies were monitored beyond their initial declaration and being signed, ratified, enshrined into law and implemented in practice. While policies can be agreed upon at international and national levels, it is even more critical that these policies are implemented at a local level. This ensures buy-in from the people that the policies are designed to support, as set out in the TA. Thus, the data collected indicates (classifies) whether the policies were implemented at regional (sub-national), national or international levels as per the TA. This means the data collected continually assessed the progress made on the announced or implemented policy throughout the observation period (the length of the transitional period). Finally, the data gathered were designated against each article, aligned with the mandate of the then TGS. As part of the data collection process, short notes and comments on each declared policy were given, which reflect some of the key points highlighted in the policy of the TGS. Collecting this latter information allowed the researcher to understand the implications of policies for everyday Sudanese during the transitional period, at least to some extent.

Methodology and coding

This study investigated the effectiveness of the TGS in achieving its mandate as stated in the 16 provisions of the Constitutional Declaration. It further investigated whether the TGS may have acted as an exacerbator of existing inner struggles. This article describes the efforts of the then TGS which are measured against the extent to which the TGS was able to move forward with its priorities into actionable policies, and enshrine these policies into law. To operationalise the efforts of the government’s policies and for measurement purposes, collected and verified data were categorised and analysed through three processes. The first process relates to the geographical level: regional, national and international. The three levels of operationalisation allow the authors to examine, to some extent, the efforts to implement these policies at the different levels across society. For example, the TGS had outlawed female genital mutilation but, in practice, it is still widely done throughout the country (UNFPA, 2020).

The second process explores whether these policies are agreed, ratified or enshrined into law. Here we explored whether the policies were implemented by the judicial, legislative and institutional bodies or law enforcement authorities. At the time of data collection, Sudan’s Transitional Legislative Council was yet to be formed, which restricted the possibility of further analysis. However, since this function is stipulated in the agreement, we did not omit this variable but acknowledge this would have been a missing component of the TGS efforts. In turn, this would have an impact on any government’s ability to deliver on its policies. Nevertheless, while there was not a functioning legislative body or council, state institutions were functioning and the TGS made attempts to reform this sector in line with its efforts to achieve provisions within the agreement.

The third process explored whether the policies were implemented into practice by the authorities, that is, police, governors, institutions and judicial authorities. This approach allowed the analysis to assess progress and examine whether it may have acted as an exacerbator of existing inner struggles.

Data limitations

While the analysis assesses the efforts of the TGS, some shortcomings were faced. First, since the data relied on a variety of sources, the data collection process hinged on what had been reported and, often, due to the slow and bureaucratic systems in place in Sudan, it became difficult to fully capture what exactly had been done, how effective the policies were and at what operational level they were being implemented. In essence, a policy might be announced at the national level. However, at the regional level, that same policy might be captured in one state and not in all states, this speaking to a variation in delivery, which means some efforts by the TGS did not fully reflect the spatial dimensions or dimensional analysis of Sudan’s TA. Monitoring the full evolution of TGS policies in Sudan requires substantial field research to confirm that the policies were being implemented at state and community levels.

Second, while the data collection approach was rich, the very nature of triangulation of data was challenging since the perspective collected could not always be standardised across different data points. This means it became difficult to follow up on nuances that emerged from the data collection; hence the analysis can only remain a snapshot of the two-year period that the TGS was in power for. This means the analysis cannot generalise the findings at different levels, which restricts the inferences and claims made but does not limit the overall contribution of the paper.

Third, the data collected could not capture other controlling or intervening variables. For example, during the two years, Darfur’s instability may have contributed to restricting the TGS from implementing policies. Capturing other controlling variables would have provided the analysis with an opportunity to make more robust inferences. As a result, the analysis cannot make statistical inferences, but provides an overview of progress by the TGS in line with the TA.

Finally, the authors are aware that democratisation and political transformation can take a long time to be achieved and that the two-year assessment conducted in this article is not exhaustive or conclusive of the overall efforts of the TGS and its efforts to deliver on the TAs. Considering the pre-existing structural challenges of past regime(s), the authors chose to analyse that specific period in time from the moment the TGS was formed in 2019 until its dissolution in October 2021. The authors further assessed how successful the TGS was in meeting its mandate and agenda during that time.

Analysis of results

The TGS was mandated to address the structural issues existing from the past regime that allowed the militarisation of politics and the state in Sudan. It was tasked with implementing measures to achieve transitional justice, fight corruption, recover stolen funds, reform the economy and state institutions, serve the public, strengthen pillars of social peace and rebuild trust between all people in Sudan. When taking a closer look at the 16 provisions of the Declaration, three of the provisions make reference to addressing or resolving challenges from the past regime. For example, provision 15 stipulates: “Dismantle the 30 June 1989 regime’s structure for consolidation for power (tamkeen) and build a state of laws and institutions”.The rest of the provisions refer to generally making “reforms to alleviate the grievances” which would have not been possible during the past regime.

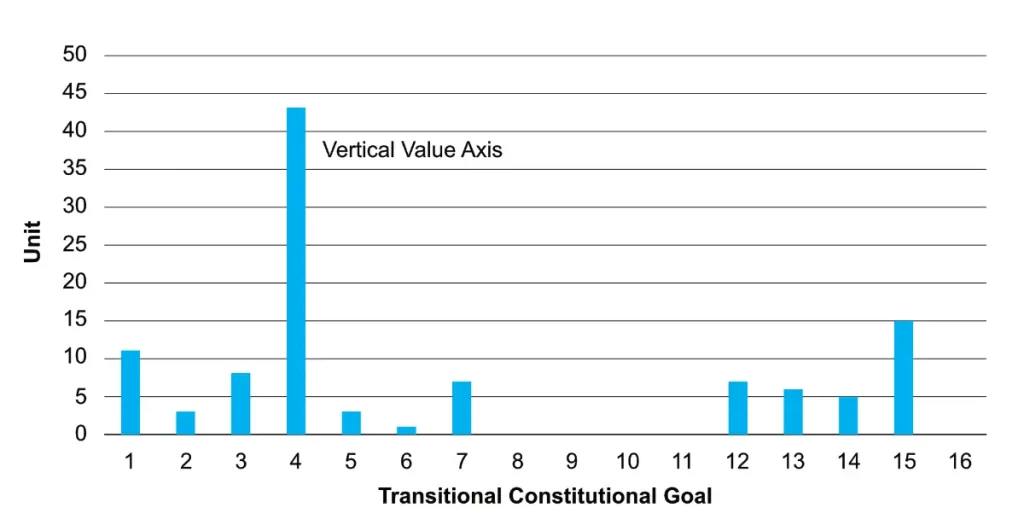

During the transitional period, the TGS had the main duty of implementing these 16 provisions in the Constitutional Declaration but many of these did not receive adequate attention. Our analysis finds that no action was taken under five of those provisions (see Figure 1 below). These include strengthening the role of young people in all social, political and economic fields (line bar 8); establishing mechanisms to prepare a permanent constitution for Sudan (line bar 9); holding the national constitutional conference (line bar 10); enacting legislation related to the tasks of the transition period (line bar 11); and forming an independent investigation committee to conduct investigations on 3 June 2019 (line bar 16). In contrast, the findings demonstrate that most of the measures were dedicated to resolving the economic crisis (line bar 4), where a total of 43 different actions were found during the period of observation and from what we could find. The least of these measures was towards working on settling the status of those who were arbitrarily dismissed from civil and military service (line bar 6).

Source: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

The slow progress and gridlock of the transition could be attributed to the Constitutional Declaration and the way the political arrangements were established. Antagonistic parties were placed as heads of the government and it was assumed that these two parties would cooperate and govern with no selfish motivations. The mandate given was too broad, vague and unrealistic given the resources available (Davies 2022:22).

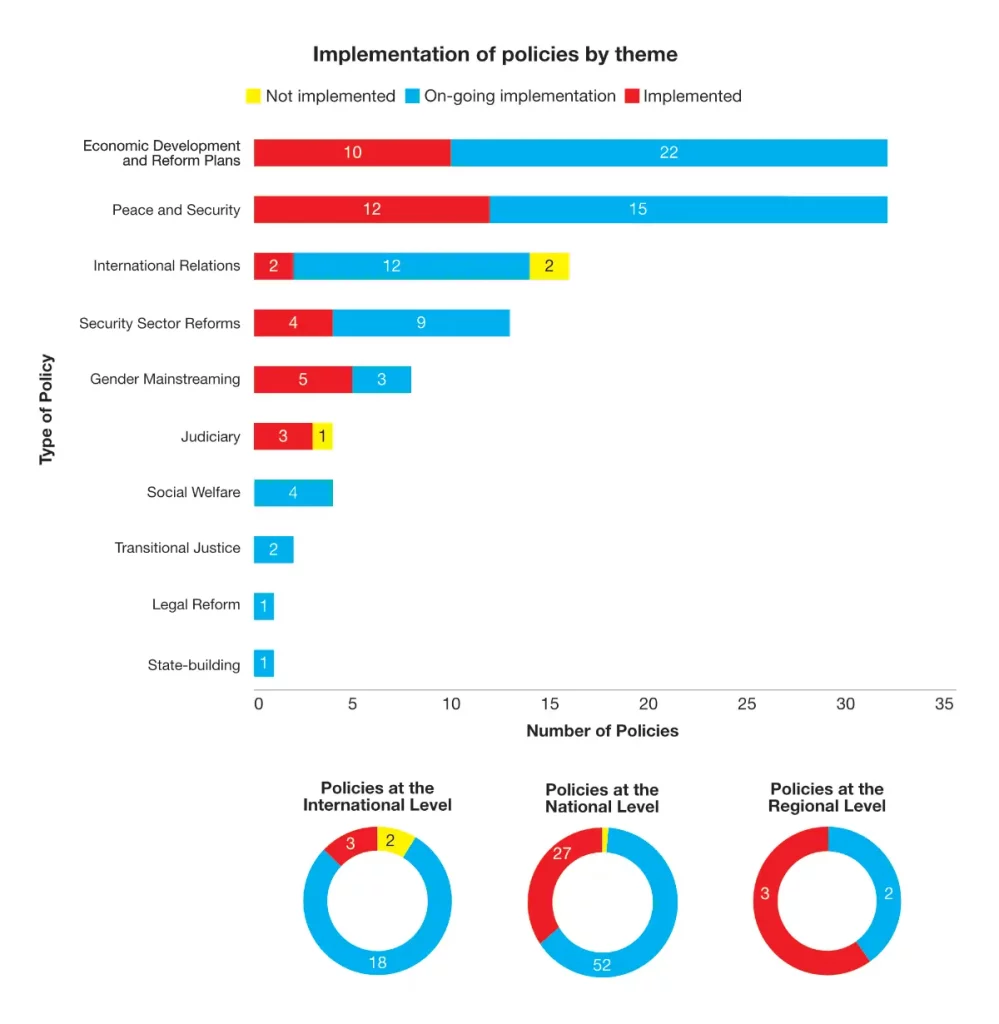

Most policy actions concerned economic development and reform plans. We observed 32 actions in this regard and 27 for peace and security matters (see Figure 2). While the TGS had a framework to follow and the mandate to bring about actionable change, it lacked a clear roadmap and specific steps to achieve its provisions and goals. This resulted in disagreements and delays in implementing reforms, such as establishing a truth and reconciliation commission and properly restructuring the security sector. In some ways, it exacerbated existing internal challenges.

Source: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

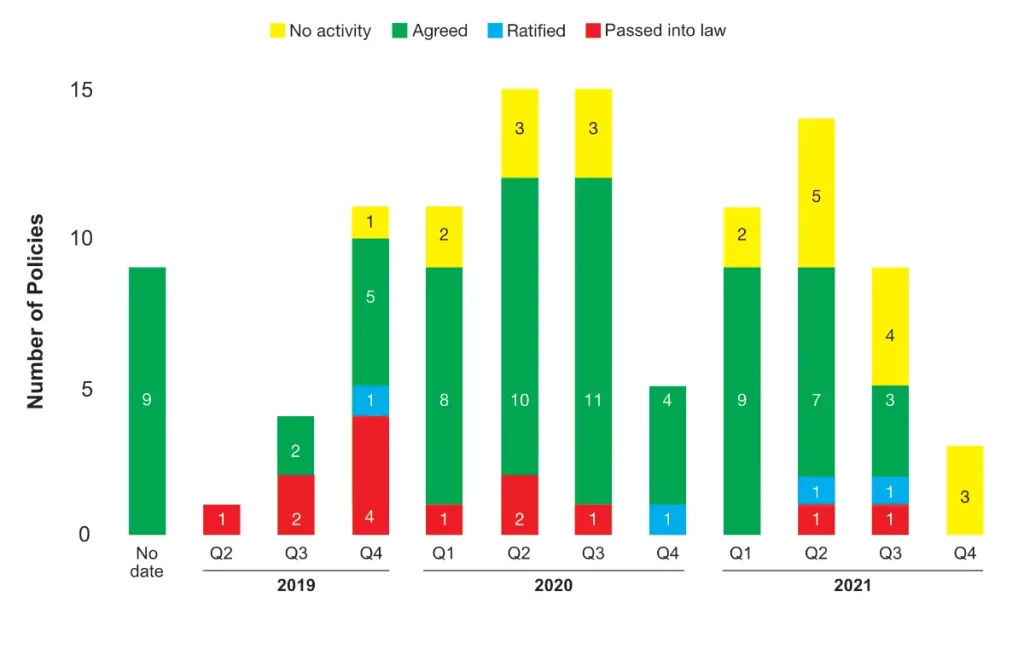

Figure 3 reveals that out of the 108 policy actions observed during the period of observation, only thirteen were enshrined into the Sudanese law. Some of these included important policies such as approving the Anti-Corruption National Commission Law. This suggests that very little was done to enforce policies into law, rendering these policies somewhat irrelevant to the efforts of the TGS and the objective of the TA to sustain peace in Sudan. Of the policies, 59 were agreed upon but not ratified or enshrined, exhibiting stagnation in the TGS policies and some limitations of the TGS to move the transition further. Figure 2 shows that most actions were taken with a national focus, and only five were taken with a regional focus. This demonstrates a lack of inclusivity in and follow up by the TGS on the different policies and their implementation. For example, despite female genital mutilation being illegal and enshrined in Sudanese law as illegal, it is still a social phenomenon that is widely practised across the country. This practice would require extensive social awareness to educate against it.

In addition, 23 of the policies implemented had an international dimension, which demonstrates the interest in meeting international expectations or donors demands. This seems to have been at the expense of ignoring troubled internal dynamics.

Source: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).

The TGS performed most of its policy actions towards achieving economic development in the country. A total of ten policies, out of 32 policies were implemented in practice. Although this is a relatively high amount of policies to be implemented in such a short time, it raises questions about the TGS’s ability to bring about economic reforms after announcing them. The TGS not only inherited the economic burden of the old regime but was also left with few resources and little room to manoeuvre the existing structure of the states. Further examination of these policies found that most of the efforts were motivated by self-interest on the part of foreign partners. For example, the clearance of the African Development Bank arrears was made possible with the support of the United Kingdom through a bridge financing of GBP 148 million, as well as support from Sweden and the Republic of Ireland.

Figure 2 above shows that sixteen policy actions were taken under the area of international relations and these actions correspond with the efforts of the TGS to address the issue of sanctions. This placed additional strain on Sudan’s access to financial resources. Efforts such as the removal of Sudan from the list of state sponsors of terrorism were positive developments, but did not materialise into sustained economic recovery. While the move unblocked the access to international financial support, most of this was in the form of debt relief. In January 2021, Sudan signed the Abraham Accords with Israel in order to normalise relations with other states and unblemish the state from sanctions. However, this was not ratified by the Sudanese legislative council as it was a non-binding agreement. Recent research found that when the population was asked whether the TGS policies had helped to resolve the economic issues of the previous regime, only 27% of the population sampled agreed with this statement (Mansour and Yousif, 2021).

On the matter of peace and security, we find that almost half of the efforts of the TGS focused on rhetoric rather than policy implementation. Policies implemented around security sector reform and military reform witnessed some progressive but limited actions. For instance, as early as October 2019, Lt. General Burhan took the decision to reform the command structure of the SAF, which was seen as a commitment to reforming the military structures and removing supporters of the former regime. The Joint High Military Committee and the Ceasefire Committee was intended to ensure the implementation of the different security arrangements as per the Juba Peace Agreement. However, the military dragged its heels in forming these bodies, suggesting that the military might not have been interested in following through on the Juba Peace Agreement. Instead, it seems the regime sought international credibility to become a security partner of other states (US or Turkey) (Refaat, 2021; Young, 2021). Further analysis on the statements put forward by the TGS remained mere statements and were not implemented. For instance, the military agreed to pass its civilian operations to the Ministry of Finance but never set up a date for this process to take place. The exclusion of certain groups in some of these actions highlights the inability of the TGS to ensure equal representation to address all grievances. For instance, the major pitfall of the Juba Peace Agreement was the absence of the other two armed groups, the Sudan Liberation Movement and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement North, to fully complete an all-inclusive peace agreement. Recent research demonstrates that only 37% of Sudanese people were optimistic about whether the peace process was going the right way (Mansour and Yousif, 2021). In addition, there was an enormous expectation gap on the political side, where a strong sense of entitlement from all parties and a relative reluctance from civil society to work with the military, hindered any advancement in the peace process (Perthes, 2024).

The Dismantling Committee made 37 decisions related to the dismantling of the former regime structures. Of those 37, eleven were implemented and seventeen were in the process of being implemented. Important measures included the decision to form committees to review concession companies working in the field of gold and to investigate facts on the gold market to regulate the gold producing companies. However, despite putting these resolutions forward, they remained in an ongoing implementation mode and never came to existence. Eleven measures linked to Bashir were implemented, including his detention and corruption charges put forward against him. Other important policy actions taken and implemented, despite being criticised for their lack of due process, were the actions of the Dismantling Committee which dismissed 151 judges in August 2020 for their association with the Bashir regime. However, with the Dismantling Committee being formed by lawyers with political and activist backgrounds, shared concern emerged that there was a possibility of selective justice to fit their own interest rather than general interest.

As a result, overall, we find that the mandates of the Constitutional Declaration lacked a grand vision for implementation. This facilitated actors to compete against one another and had an impact on the implementation process of the TA and, more broadly, the future of Sudan. In addition, the TGS failed to consider path dependencies of the previous regimes, which inhibited the TGS from being able to provide the people of Sudan with adaptive strategies that could support and circumvent existing structures set up by past regimes. As a result, we find that the transitional power-sharing agreement led by the TGS and with fragile structures, which would not necessarily be identical to long-term stability, was not successful in the case of Sudan. This article finds that there is evidence to suggest that, in the case of Sudan, civilian-led or joint civil‒military transitions have significant challenges to effectively meet their agenda. This is largely linked to the structure of the state, competing agendas from the international community but also internal capacity and lack of support from regional entities. Finally, we find evidence to suggest that, in part, the TGS in Sudan has made efforts to ensure that they work to meet their mandate but these efforts are often overridden by deep-rooted challenges, such as coups, economic challenges and the existing structures of the past regime. This, we suggest, may have played a role in intervening in and exacerbating existing inner struggles. In essence, while the TGS was going through several processes at once — state building, peacebuilding, governance restructuring — it had little capacity to manage. Since the TGS was composed of competing interests, this resulted in a lack of coordination between the TGS and critical political actors. This made the Constitutional Declaration not achievable in the long-term. We find no evidence that a comprehensive embrace of liberal peacebuilding ideals helped the TGS to deliver sustainable peace and economic prosperity. This raises the question of whether liberal peace, along with its variant, liberal democracy, is an adequate theory that should inform state building in divided societies. In fact, we find that the TGS was unable to provide the people of Sudan with adaptive strategies that could help to circumvent existing structures set up by past regimes.

Conclusion

In this article, we find that the TGS could not effectively implement the policy announcements and measures it was mandated to deliver. The results show that half, or more than half in some cases, of the statements or policies announced did not reach the implementation mode. It raises doubts over whether TAs are useful for states transitioning to democracy. In addition, questions emerge over whether transitional power-sharing agreements masked as civilian-led or joint civil-military transitions, where civil-military relations have either been non-existent or strained due to a host of interlinked issues, are effective mechanisms to move states towards democracy, or whether they simply reproduce modernised versions of military regimes designed to appease western donors and justify their self-interests.

Drawing on the case of Sudan, we have added to the literature on Sudan by demonstrating the difficulty in achieving peace through TAs. The lack of a clear roadmap with clear benchmarks to address general public interests with an equal and balanced focus across the country was missing. We also find that the TGS efforts were often focused on trying to meet international expectations and external credibility, which had an impact on efforts at home and exacerbated internal challenges. One of the biggest challenges to consolidated peace in Sudan was the TGS’ ability to dismantle the deep state created over the last 60 years. This is partly because no single party can govern Sudan without the support of the security sector, which has been a part of restructuring state power and remains one of the most significant threats to Sudan’s democracy. Sudan’s history and legacy of military rule and internal conflict leave the country at risk of experiencing continued outbreaks of violence and the possibility of regressing to an authoritarian regime. Thus, as the recent coup in Sudan has demonstrated, it needs to create structures that reduce corruption and risks and that develop effective adaptive stabilisation policies to support the restructuring of state power towards democracy. Finally, the case of Sudan has helped our conceptual understanding of implementing TAs in Africa through somewhat western liberal peacebuilding efforts. The article should be used as a springboard to assess the effectiveness of existing and future TAs and to explore how these agreements impact on the internal dynamics of states in transition.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for further helpful comments and suggestions from colleagues at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Dr Jihad Mashamoun, Tinashe Tony Chikafa, journal editors, peer reviewers and our partners at the Training for Peace programme.

Reference list

Ali, A., Elbadawi, G.I., and El-Batahani, A. (2005) The Sudan’s civil war: Why has it prevailed for so long? Chapter 10. In: Collier, P. and Sambanis, N. eds. Understanding civil war: Evidence and analysis. Volume I: Africa. Washington DC, World Bank.

Al-Jazeera. (2020) Sudan PM Abdallah Hamdok survives assassination attempt. Al- Jazeera [Internet], 9 March. Available from: <http://www.ajazeera.com/news/2020/3/9/sudan-pm-abdalla-hamdok-survives-assasination-attempt> [Accessed 9 August 2020].

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). (2020) Sudan army quells Khartoum mutiny by pro-Bashir troops. BBC [Internet], 15 January . Available from: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-51112518 [Accessed 9 August 2020].

Beswick, S. (1991) The Addis Ababa Agreement: 1972-1983 Harbinger of the Second Civil War in the Sudan. Northeast African Studies, 13 (2‒3), pp.191‒215.

Davies, B. (2022) Sudan’s 2019 constitutional declaration: Its impact on the transition. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/sudans-2019-constitutional-declaration-its-impact-on-the-transition-en.pdf> [Accessed 14 May 2024].

Deng, F. (1995) War of visions: Conflict identities in the Sudan. Washington, DC, The Brookings Institution.

Duursma, A. (2020) African Solutions to African Challenges: The Role of Legitimacy in Mediating Civil Wars in Africa. International Organization, 74(2), pp. 295-330.

El-Battahani, A. (2006) A complex web: Politics and conflict in Sudan. Conciliation Resources, 18, pp. 10‒13.

Elhadary, Y. and Abdelatti, H. (2016) The Implication of Land Grapping on Pastoral Economy in Sudan. World Environment, 6 (2), pp. 25–33.

ElNur, I. (2009) Contested Sudan: The political economy of war and reconstruction. London, Routledge.

Gallopin, J-B. (2020) Bad Company: How dark money threatens Sudan’s transition. European Council on Foreign Relations, no. 324, pp. 1‒31 [Internet]. Available from: <https://ecfr.eu/publication/bad_company_how_dark_money_threatens_Sudans_transition/> [Accessed 23 September 2020].

Goodluck J, Chambas, M.I., Olonisakin, F, Akinola, A.O., Kassi Bou, J. C., Toure, B.A., Olojo, A, Darkwa, L.A.O “Africa in Perspectives: Spotlight on West Africa.” Moderated by Andrew E. Yaw Tchie. London, United Kingdom: Royal United Services Institute, 2020. Available at: <https://www.rusi.org/events/open-to-all/africa-in-perspective—spotlight-on-west-africa>. [Accessed August 2020].

Human Rights Watch. (2004) Darfur destroyed, ethnic cleansing by government and militia forces in Western Sudan. Brussels, New York, Washington D.C: Human Rights Watch [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.hrw.org/report/2004/05/06/darfur-destroyed/ethnic-cleansing-government-and-militiaforces-western-sudan> [Accessed 9 August 2020].

Ibrahim, M. (2015) Artisanal mining in Sudan – opportunities, challenges and impacts. Paper presented at 17th Africa Oil Gas Mine, 23‒26 November 2015, in Khartoum [Internet]. Available from: <https://unctad.org/meetings/en/Presentation/17OILGASMINE%20Mohamed%20Sulaim- an%20Ibrahim%20S4.pdf> [Accessed 12 September 2020].

Khalid, M. (1990) The government they deserve: The role of the elite in Sudan’s political evolution. London, Kegan Paul.

Mansour, A. and Yousif, A. (2021) Attitudes of the Sudanese people towards the performance of new transitional government: An exploratory Study. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations,Vol 15(2), pp. 65-75.

McAuliffe, P. (2017) Transitional Justice, liberal peacebuilding and the endogenous determinants of transformation. In: Transformative Transitional Justice and the Malleability of Post-Conflict States [Internet]. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783470044> [Accessed 9 August 2020].

Mamdani, M. (2009) Saviours and survivors: Darfur, politics, and the war on terror. New York, Pantheon.

Perthes, V. (2024) Roundtable at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI): Lesson Learned on UNITAMS. EPON/TfP Seminar. 5 June 2024.

Radio Dagbana. Available from: <https://www.dabangasudan.org/en> [Accessed 9 August 2020].

Refaat, T. (2021) Sudan, Turkey re-sign deals worth $10 billion. Sada Elbalad English [Internet].Available from: <https://see.news/sudan-turkey-re-sign-deals-worth-10-billion> [Accessed 20 December 2021].

Richmond, O. (2013) Failed Statebuilding Versus Peace Formation. Cooperation and Conflict, 48 (3), pp. 378–400.

Schedler, A. (2007) Electoral Authoritarianism in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. DOI: 10.4135/9780857021083.n21.

Stigant, S. (2023) What´s Behind the Fighting in Sudan: The ongoing confrontation between the military and Rapid Support Forces undermines stability in Sudan and the Horn of Africa. United States Institute of Peace. Available from: <https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/whats-behind-fighting-sudan> [Accessed August 2023].

Sudan Constitutional Declaration, 2019. Accessed August 11, 2021. Available at: https://constitutionnet.org/vl/item/sudan-constitutional-declaration-august-2019 [Accessed August 2021].

Sudan Tribune. (2021a) Darfur armed groups accuse Sudan’s military of delaying security arrangements. Sudan Tribune [Internet], 29 May. Available from: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article69613> [Accessed 28 August 2021].

Sudan Tribune. (2021b) US’s power pledges more support to Sudan calls to disband the RSF. Sudan Tribune [Internet], 4 August. Available from: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?iframe&page=imprimable&id_article=69902> [Accessed 29 August 2021].

Tchie, A. (2019) How Sudan’s protesters upped the ante and forced al-Bashir from power. The Conversation [Internet], 11 April. Available from: https://theconversation.com/how-sudans-protesters-upped-the-ante-and-forced-al-bashir-from-power-115306 [Accessed 25 October 2019].

Tchie, A. and Ali, H. (2021) Restructuring state power in Sudan. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal [Internet], 16 (1), pp. 41‒51. Available from: <http://dx.doi.org/10.15355/epsj.16.1.41> [Accessed 20 August 2020].

Tchie, A. and Mashamoun (2022) After the Coup: Regional Strategies for Sudan. Available at: <https://africanarguments.org/2022/01/after-the-coup-regional-strategies-for-sudan/ > [Accessed August 2022].

Tchie, A. (2023) Enhancing the African Union´s function in supporting transitional governments in Africa. Training for Peace (TfP) Report. 2 August 2023. Available at: <https://trainingforpeace.org/publications/enhancing-the-african-unions-function-in-supporting-transitional-governments-in-africa/> [Accessed August 2023].

The New Arab. (2017) Sudan’s Bashir orders six-month ceasefire extension in three regions. The New Arab [Internet], January 16. Available from: <https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2017/1/16/sudans-bashir-orders-six-month-ceasefire-extension-in-three-regions> [Accessed 9 August 2020].

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2020) Sudan: The First State of Environment and Outlook Report 2020: Environment for Peace and Sustainable Development. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme [Internet]. Available at: <http://www.unep.org/resources/report/sudan-first-state-enviroment- outlook-report-2020> [Accessed 24 October 2021].

United Nations Populations Council. (2020) Voices from Sudan 2020: A Qualitative assessment of Gender-Based Violence in Sudan. Khartoum: United Nations Population Fund, 2020, Available at: <http://www.reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNFPA_16th.pdf> [Accessed October 2021].

Young, A. (2021) Exploring new security partnerships with Sudan. US Department of State [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.state.gov/dipnote-u-s-department-of-state-official-blog/exploring-new-security-partnerships-with-sudan/> [Accessed 24 October 2021].