Abstract

In 1986, during a second decade of severe droughts and famine, an Intergovernmental Authority was established by Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan to focus on the problems of drought and desertification. At the same time, however, this Authority inevitably took upon it the related tasks of conflict resolution and development. Later on Uganda and Eritrea joined the renamed Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). An overview is given of conflicts in the region, and in Sudan. What the paper concentrates on, however, is IGAD’s patient and apparently quite effective role in managing and resolving conflict, especially within Sudan itself. Appropriate details are given, stubborn and shifting positions of governments and rebel movements in Sudan are summarised, and concluding recommendations, warnings and encouragements are provided.

1. Inside a turbulent region: IGAD’s commitment to conflict resolution

Ever since its foundation in 1986 the Intergovernmental Authority on Drought and Desertification (IGADD), later renamed Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), has faced the enormous task of resolving conflicts in the Horn Of Africa. The Horn of Africa remains one of the most volatile regions on the continent, where internal civil wars have led to the total collapse of Somalia, the secession of Eritrea from Ethiopia, the ongoing border war between Eritrea and Ethiopia as well as the polarisation of Northern and Southern (and the Nuba Mountains people) Sudanese advocating for Islamic and secular state conceptions respectively. Conflict in the region, as in other parts of Africa, is not only “internationalised” (Adar 1998a), but it leads to what has been called “conflict triangulation” (Lyons 1996:88; Midlarsky 1992).

Uganda served as a base and arms conduit for the Southern Sudanese Anya Nya rebels in the 1960s and continues to play the same role for the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM)/Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). The SPLA also receives military support from Zimbabwe, Namibia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Israel and the United States. However, the SPLA’s main source of arms is the international market, with some of its arms coming from those captured by its forces from the Sudanese army. Sudan, on the other hand, supports William Kony’s (formerly with Alice Lakwena who now lives in a refugee camp in Kenya) Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the West Nile Bank Front (WNBF) which are fighting Yoweri Kaguta Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA), renamed Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF). The LRA is trained by Sudan at Jebelin, Kit II, and Musito and by 1997 numbered about 6,000 strong. Sudan also provided a base as well as material and logistical support to the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) during their struggle against Ethiopian regimes. The EPRDF was largely composed of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). While Sudan harboured the EPLF and EPRDF, Ethiopia gave the SPLA safe havens for its military operations against Khartoum (Simons 1995; Lyons 1995 and Anyang’ Nyong’o 1991).

Whereas the US gave Sudan massive military support, particularly during the reign of President Numeiri (1969-1985), Sudan now receives military aid from China, Russia, Yugoslavia, Iran, Iraq and Libya. China has since 1994 been the principle supplier of arms to Sudan, with Sudan offering China oil concessions. China is reported to have sold Sudan SCUD missiles in 1996 at the cost of a $200m loan from Malaysia, another country prospecting oil in Sudan. The conservative Islamic Gulf states, for example, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, support the SPLA because of their fear of the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Sudan. Sudan was the only Sub-Saharan African country that supported Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War (Adar 1998a:46). Apart from these linkages, there are other pertinent concerns for IGAD in the region and beyond, which deserve some observation. Sudan supports other militias operating in the continent, for example, Islamic Group (Egypt), Islamic Salvation Front (ISF, Algeria), Islamic Oromo Front (IOF, Ethiopia), Somali National Alliance (SNA, Somalia), Ethiopian Islamic Opposition (EIO, Ethiopia), Al-Ittihad al-Islamiya (Islamic Union, Somalia), Tunisian Islamic Front (TIF, Tunisia), and other Islamic groups in Kenya, Niger, Gambia and Senegal. These groups are trained in areas such as Damazin, Equatoria, and Hamesh Koreb near Eritrea. These are some of the wider problems which face IGAD in its conflict resolution initiatives in Sudan.

Egypt is faced with a dilemma. First, it is concerned with the growing Islamic fundamentalism in Sudan which spills over into its territory. Indeed, it is because of Sudan’s unhappiness with the Egyptian pro-Western stance that Khartoum was alleged to have planned the assassination of Hosni Mubarak during the 1995 Organisation of African Unity (OAU) meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Adar 1998a:47 and Africa Confidential July 7,1995:1). Second, the Egyptian dependence on the Nile River water makes the regime in Cairo wary of the implications of secession and independence of the South and they therefore support a unified Sudan. Third, the long standing Sudo-Egyptian dispute over the Halaib territory near the Red Sea adds to the complexity of the situation between the two countries. Egypt is not the only country that is fearful of the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. The other countries which are targeted by the Sudanese National Islamic Front (NIF) include the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (at least before its civil war broke-out), Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and Eritrea, with the latter fighting against the Eritrean Islamic jihad (Africa Confidential June 9,1995:2-3). The visit by Laurent Kabila of the DRC to Ethiopia in April 1998 is an indication of this wider “conflict triangulation” in the region (Ethiopia Herald 1998 and Horn of Africa: The Monthly Review 1998).

Conflict in the area has, at one time or another, experienced inter-regional dimensions, with the 1977-78 Ethio-Somali and the on-going 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean wars being good examples. The Ethio-Eritrean war has also weakened the Ugandan-Ethiopian-Eritrean coalition against Sudan. The irony of the scenario is that it is likely to help the IGAD peace process because Sudan may soften its stance in the Sudo-SPLM negotiations. The fact that Uganda is locked in the DRC civil war is an added advantage to the Sudanese. The civil war in the DRC occupies the Rwandan, Ugandan and the SPLA’s human and material resources because of their support for the rebels fighting the Kabila regime (Horn of Africa Bulletin Nov-Dec 1998). The arms deliveries to the DRC are mainly carried out by the three East African based air carriers such as Air Alexander International, Busy Bee, Sky Air, Planetair, United Airlines as well as Sudanese and Ugandan military aircraft.

The on-going 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean war, which erupted because of the disputed Badme area, has added a new dimension to the realpolitik in the region, with over 50,000 Eritreans expelled from Ethiopia and more than 10,000 Ethiopians losing their jobs in Eritrea. It is because of the Ethio-Eritrean war that a rapprochement has been re-established between Ethiopia and Sudan, severed previously as a result of the assassination attempt on Mubarak in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopia has not only closed the SPLA’s base in Gambela in western Ethiopia but has also agreed with Hussein Mohamed Aideed of Somalia to prevent the OLF operations against Ethiopia from their bases in Somalia. These are some of the immediate and long term challenges that face IGAD, particularly with respect to conflict resolution in Sudan. Conflicts in the Horn of Africa not only create operational and functional difficulties for IGAD but the multiplicity of the non-state actors, with national, regional, continental and global interests, provide additional multifarious impact on IGAD. The paper addresses this complex scenario in relation to IGAD. Specifically, it examines the role of IGAD in conflict resolution in Sudan.

2. IGAD’s regional dynamics and its linkage to Sudan

The development of more specific responsibilities in the region

The 1980s and 1990s have witnessed the emergence of the “second wave” of regional functional organisations in Africa (Shaw 1995; Nyangoro & Shaw 1998). These second-generation functional organisations perform tasks which conform to the idea of “African solutions to African problems” conceptualised within the context of “African Renaissance”. These regional International Governmental Organisations (IGOs) are increasingly performing tasks which go beyond socio-economic functional arrangements to those that fall within the general purview of realpolitik security perspectives. We are witnessing a shift away from the concept of “African solutions to African problems” to “African ‘sub-regional’ solutions to African ‘sub-regional’ problems”. This is a new phenomenon in the New World Order, at least with respect to Africa, and is an important one given the tendency of the Western countries’ movement towards isolationism in the post-Cold War era. The cases in point are the military involvement of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Economic Community of West African States Cease-Fire Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) in Lesotho and Liberia respectively (Shaw & Okolo 1994; Magyar & Conteh-Morgan 1998). This is not to argue that the role of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in conflict resolution in the continent has become irrelevant. What is emerging, is that African international relations are increasingly characterised by increased involvement of non-state actors in conflict resolution missions (Cleary 1997).

It is in this same vein that IGADD was transformed, that is, from an IGO responsible for ecological (drought and desertification) and humanitarian problems to one committed to conflict resolution, prevention and management. IGAD’s role can be seen in this larger context. It was the catastrophic droughts of the 1970s and the 1980s in the Horn of Africa which led to the establishment of IGADD, with the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) initiating the process. The founders of IGADD charged the organisation with the responsibilities of: alerting the international community and humanitarian agencies about emergencies in the region, bringing resources needed to cope with the situations, co-ordinating emergency situations and serving as an early warning system for the region. With financial support from Italy, IGAD established at the regional and the national levels an Early Warning and Food Information System (EWFIS) with remote sensing components (UNEP 1996:4). In conjunction with the “Friends of IGAD” (Canada, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Britain and the US) and other groups such as the Coalition for Peace in the Horn (US), European Working Group on the Horn (Canada) as well as other NGOs, IGAD continues to meet some of its obligations. However, some of the present stumbling blocks to IGAD’s peace process include lack of resources, capacity to implement programmes, transparency and co-ordination, grass-roots level participation and democratisation in general; and instability in the region.

In 1996 EWFIS estimated that its members required more than 21 million metric tons of cereals annually to meet the needs of those affected in the region. The 1996 IGAD total food aid imports reached 805,000 metric tons, with Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, Sudan and Kenya accounting for over 231,000, 186,000, 167,000, 117,000 and 74,000 metric tons respectively. The other two IGAD members, Uganda and Djibouti, received food aid totalling 15,000 metric tons each in the same period (IGAD 1996; IGAD 1999). IGAD encourages intra-regional trade to promote self-sufficiency and sustainable development as well as co-operation among its members. However, food deficits still account for some of the problems facing IGAD, with Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea being the largest recipients in the 1990s.

Some of the immediate challenges facing the countries in the Horn of Africa and IGAD as well as national and international non-state actors operating in the region have been drought, famine, refugees as well as victims of landmines and war. Conflict remains the major contributing factor with far reaching ramifications to the disasters because of instability in the region. As Table One demonstrates, the emergency food aid which the IGAD members (including Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania) received between 1985 to 1994 was more than double the regular food aid. For example, the emergency food aid which they received as a percentage of the total food aid in 1985, 1992 and 1994 accounted for more than 67%, 85% and 105% respectively. As Table One shows the Emergency Food Aid for 1985, a year before IGADD was founded, accounted for over $378 million compared to nearly $140 million Regular Food Aid. Between 1989 and 1994 the Emergency Food Aid increased steadily in comparison to the Regular Food Aid. Thousands of people died of famine in Ethiopia and Sudan between 1984 and 1985 mainly because of famine which affected most of Sub-Saharan Africa and led to the formation of the International Conference on Assistance to Refugees in Africa (ICARA) (Kibreab 1994).

Table 1. Food aid trends in the greater Horn of Africa, 1985-1994 ($millions)

| 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | |

| Emergency Food Aid | 377,589 | 197,207 | 25,755 | 140,281 | 79,172 | 191,789 | 200,598 | 242,186 | 247,926 | 260,690 |

| Regular Food Aid | 183,311 | 114,620 | 113,696 | 90,032 | 57,864 | 40,910 | 32,620 | 41,321 | 79,954 | 86,740 |

Source: USAID 1995

The original founders of IGADD, Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan (later joined by Eritrea and Uganda), concerned with the perpetual conflict and humanitarian situations in the region, with its 133 million people, recognised that sustainable economic development of the Horn of Africa was contingent upon peace and security. Regional co-operation therefore becomes a necessity, particularly in areas where the “security of the state and its rulers are threatened” (Clapham 1996:120; Buzan 1983). It was the 1973-74 famine which led to the collapse of Emperor Haile Sellasie and instigated unrest in Sudan. Similarly, the 1984-85 famine contributed to the downfall of Numeiri and weakened Mengistu Haile Mariam’s regime paving the way for its collapse.

The problems in the IGAD region are also compounded by refugees and the internally displaced people. The civil war in Sudan has killed more people than any other war since World War II. It has killed more people than the conflicts in Bosnia, Kosovo, Somalia, Afghanistan, and Chechnya combined. For the past fifteen years it has claimed the lives of more than 60,000, 5,000, 1,200, and 180 people per year, per month, per week and per day, respectively. Over 80% of Southern Sudanese are internally displaced. More than 100,000 died of famine in 1998 alone (Fisher-Thompson 1999; Winter 1999). In 1990, for example, there were over 2 million refugees in the area (Bakwesegha 1994:5). Together with internally displaced people the total number of refugees in the IGAD region reached 5 million in 1994 (USAID 1994). By 1991 there were nearly 1 million Ethiopians who had fled their country due to the civil war and famine. The UNHCR repatriated 31,617 (1995), 62,000 (between 1993 and 1996) and 4,400 (1997) Ethiopian refugees from Djibouti, Sudan and Kenya respectively (UNHCR 1997). On the other hand Ethiopia received more than 338,000 refugees early in 1997, of whom 285,000, 35,500, 8,000 and 8,600 were Somalis, Sudanese, Djiboutians and Kenyans, respectively. The 1991 overthrow of Siad Barre and the continued intra-clan and sub-clan “battle of territorial control” have forced more than 900,000 Somalis to flee their country, mainly to the neighbouring countries of IGAD member states. By the time Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993, over 900,000 Eritreans had fled their country (Adam 1995). The UNHCR spent over $260 million between 1994 to 1995 to repatriate the Eritreans, mainly from Sudan (UNHCR 1998). The refugee problem in the IGAD region is not only a function of the perpetual civil wars, but also a product of the environmental and economic factors which contribute to the complexity of the situation.

IGAD’s growing involvement in the Sudan peace process

IGAD became more involved in conflict resolution in Sudan from 1990, when Sudan requested the organisation to assist in the peace process with the Southern rebels. This was the second time in the history of the civil war in Sudan that Khartoum decided to make its internal affairs a subject for discussion by other interested parties to the conflict, like IGAD. The first time was in 1972 when Numeiri entered into negotiations with the Southern Sudanese rebels. The leadership in Sudan viewed IGAD as the only vehicle that could prevent external actors from infringing on its internal affairs. In other words, IGAD was seen “as a means to forestall the intervention of other powers with greater leverage” (Deng et al 1996:161-162) and also as a regionally and indigenously generated IGO which cuts across ethnopraxis (Avruch & Black 1991). Yet, when other members of IGAD – Ethiopia, Eritrea and Uganda – pressured Sudan through IGAD to resolve the problem in the South, Sudan quickly invoked its sovereignty (Deng et al 1996). This rigidity on the part of Sudan notwithstanding, the leadership in Sudan accepted that the involvement of IGAD in its internal affairs is legitimate. IGAD therefore responded by gradually transforming itself into an organisation responsible for conflict resolution in the region. It has established four hierarchical and complementary structures designed to deal with problems facing the region. They include the Authority of Heads of State and Government which meets once a year; the Council of Ministers, mainly Foreign Ministers, that meets twice a year; the Committee of Ambassadors/Plenipotentiaries attached to the Headquarters whose responsibilities are to advise and guide the Executive Secretary; and a Secretariat, headed by an Executive Secretary, appointed by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government for a term of four years, renewable once. These administrative structures have expanded the objectives and scope of IGAD in the region. The establishment of the 1993 Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management and Resolution by the OAU is seen by IGAD as a complementary mechanism for regional co-operation (Zartman 1995a; Zartman 1995b). IGAD was conceived within this broad context, with a view to promote regional dynamism conducive to peace in the Horn of Africa even if the end results were minimal. It was through IGADD’s diplomatic initiative that Mengistu and Siad Barre agreed to sign the 1988 historic agreement which led to the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between Ethiopia and Somalia (Simons 1995:69, Lyons 1995:245). The rapprochement between the two countries was historic because they had fought the 1977-78 bitter war which involved the United States, the Soviet Union and Cuba.

With reference to the 1997 Cairo Accord involving the leading Somalia factions and endorsed by the League of Arab States, IGAD stated in its Declaration adopted by the 17th Session of the Council of Ministers in Djibouti 15th March, 1998 and reaffirmed by the IGAD Heads of State and Government, that it is prepared to engage in “consultation with all those who are prepared to contribute to the peace process in Somalia on the basis of the IGAD initiative and on condition that they refrain from engaging in parallel initiatives and limit themselves to supporting IGAD’s efforts” (IGAD 1998). The issue of the centralisation of the Sudanese peace process within the IGAD framework is an important one for the organisation, particularly with respect to the co-ordination of the peace process.

The membership of Eritrea and the new leadership in Ethiopia gave IGAD a new regional dynamism and stimulus in the peace process, initially at least, particularly because Sudan had provided sanctuary for the former allies, EPLF and EPRDF, who are now engaged in a devastating war. IGAD’s original hope was that Eritrea and Ethiopia would provide a moderating influence on Sudan. However, this optimism never materialised following the Eritrean severance of diplomatic relations with Sudan in December 1994 accusing Khartoum of supporting the Eritrean Islamic jihad (Deng 1995). As a quid pro quo, Eritrea has been giving military, political, moral and logistical support to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) fighting the Bashir regime. In a show of displeasure with the Sudan Government, Eritrea handed over the Sudan embassy in Asmara to the NDA. The differences between the two countries entered a new phase in 1997 when Sudan, with Libyan disapproval, opposed the Eritrean application for membership to join the League of Arab States. The planned investments in airports and hotels in Eritrea by a multimillionaire Saudi Arabian businessman, Hani Yamani, Chairman of Air Harbour Technologies Group, is likely to tip the balance in favour of Eritrean admission into the League. The amalgamation of ten Eritrean opposition movements in 1999 with the Sudo-Ethiopian mediatory efforts into the Eritrean National Forces Alliance (ENFA) and the on-going Ethio-Eritrean war, which began on May 6, 1998, continue to undermine IGAD’s peace process in the region. The denial of entry both into Djibouti (IGAD’s Headquarters) and Ethiopia by IGAD’s Executive Secretary, Dr. Tekeste Ghebray, an Eritrean, after attending IGAD Partners’ Forum (IPF) meeting on Somalia in Rome, November 1998, is a clear testimony to the difficulties that face the organisation.

One of the central concerns of the US is the Libyan-Sudanese support for Islamic fundamentalism and Islamic organisations such as Hamas, Hezbollah, Gamaat Islamiya, and Abu Nidal, which Washington considers to be terrorists. The support by the Bush Administration for the partition of Sudan based on the Ethiopian model of regionalism (ethno-regional federalist arrangements) was not radically different from what the SPLM and the other rebels have advocated since the 1950s, and which has been inscribed in the IGAD Declaration of Principles (DOP). It is based on the idea of equality in diversity, where the rights of individuals are clearly provided for in the Constitution. The Clinton Administration, through the Greater Horn of Africa Initiative (GHAI), launched in 1994 by the USAID Administrator, J Brian Atwood, works in partnership with IGAD and has endorsed its DOP as the framework for resolving the impasse in Sudan. The GHAI works in conjunction with other US Government Departments and agencies with interests in the region, for example, USAID Horn of Africa Support Project (HASP), Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (FDA), Sudan Transition Assistance for Rehabilitation (STAR), and Office of Food for Peace (FFP); and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM), among others, all of which support the IGAD peace process.

The Clinton Administration’s policy in Sudan is based on the long standing policy of combating terrorism and regional extremism, supporting an end to civil war, calling for respect for human rights, and promoting the humanitarian situation (US Department of State, Testimony: E. Brynn on US Policy Toward Sudan 1995:6). The August 1998 US bombing of a pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum suspected of producing chemical weapons was carried out within this larger context. The US bombing of the factory was in response to the simultaneous bombings of American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, which killed nearly 500 people and injured over 5,000 in Kenya alone. The accusations by the international relief workers against the Sudanese Government for using chemical weapons against the rebel strongholds in the South is likely to confirm the US claims (Lynch 1999; Denyer 1999).

To help it cope with wars and disasters in the region IGAD established an Emergency Fund and pledged to raise over $1 million. The Friends of IGAD gave $500,000 to the fund, of which $300,000 was donated by the US (Horn of Africa: The Monthly Review 1998:2). The US has also earmarked over $7.4 million for IGAD over the next five years beginning from 1998. The revitalisation of IGAD, particularly in 1996, to an IGO responsible for economic co-operation, conflict prevention, management and resolution, and humanitarian affairs has enhanced its mandate and expanded its objectives. With “positive sovereignty” derived from effective state control eroding/having eroded in the region, IGAD will continue to experience functional and operational difficulties. On the other hand turbulence in the region has enhanced IGAD’s role to deal with internal conflict situations, traditionally regarded as the sole preserve of sovereign states. Apart from these recurring problems, the IGAD region, as other parts of Africa do, houses authoritarian and repressive regimes, with some leaders like Moi of Kenya (one of the longest serving presidents in Sub-Saharan Africa) presiding over a kleptocratic state. The civil war in Sudan, fought on secular and Islamic ideological perspectives, has forced the successive regimes in Khartoum to centralise power within the ambit of the Presidency, using the state as an instrument for security, war and oppression.

3. Inside a turbulent state: IGAD’s peace process in Sudan

Islamisation and minority religions

The civil war which broke out in 1955 between the Anya Nya of the South and the Northern Sudanese regimes ended in 1972 and led to the reduction of military and logistical support which the rebels received from the Central Africa Republic, Ethiopia, Kenya and Zaire as well as military training by the Israelis. The Addis Ababa Accord was a landmark peace process brokered by the World Council of Churches (WCC) and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. Sudan, under the leadership of Numeiri, accepted the terms of the Accord which included, among other things, religious rights and autonomy for the Southern Sudanese and other marginalised peoples. The Accord established some form of regionalism in the area, with the formation of Southern Sudan Provisional Government (SSPG), the Nile Provisional Government (NPG), the Anyidi Revolutionary Government (ARG), the Sue River Revolutionary Government (SRRG), and the Sudan-Azania Government (SAG), all of which incorporated specific ethnic groups. However, a rift which occurred between the so-called “outsiders” (comprising those who went into exile and those who remained in the bush fighting the Sudan Government) and “insiders” (those who remained in the country and formed political parties and were also accused of collaborating with the regimes – a mistrust which still prevails in the South) undermined tangible progress in consolidating unity and autonomy. Faced with the threat of growing radical Islamic fundamentalism and deteriorating economy at home, Numeiri abrogated the terms of the Accord and reintroduced Islamisation. The decision led to the re-emergence of the Southern Sudanese liberation movements in 1983. The SPLM/SPLA and other liberation movements have been fighting for self-determination, democracy and religious rights (Deng & Gifford 1987).

The incorporation of the Islamic sharia laws into the Constitution has led to the centralisation of power and the adoption of a theocratic state in Sudan, some of the consequences of which have been the marginalisation and repression of the non-Muslims (Adar forthcoming). The state is therefore used as an instrument of oppression and by extension constitutes the centre of the contestation between the North and the South. In this regard, it is fair to argue that ever since the civil war broke out in 1983 the Sudanese state has gradually been “criminalised” through intra-state conflicts. Who are the major contenders in the protracted Sudanese war against the regimes in Khartoum? What are the main contentious issues at stake? What are the policy positions of the centripetal and centrifugal forces? What role has IGAD played in its attempt to broker peace in Sudan? Who are the other state and non-state actors concerned with the situation in Sudan and what are their roles and relationships with IGAD?

The issue of self-determination

As in other parts of Africa where civil wars are commonplace, intra-factional conflicts have at one time or other undermined the unity and strength of the liberation movements in Sudan. The major contenders in the liberation struggle in Sudan have included among others, the SPLM/SPLA, the Southern Sudan Independent Movement/Army (SSIM/A), the Patriotic Resistance Movement of Southern Sudan (PRMSS), the Southern Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SSPLM)/Anya Nya Two, and the Nuba Mountains Solidarity (NMS). The 1991 split which occurred between John Garang (Dinka) and Riek Machar (Nuer), the dominant personalities within the SPLA/SPLM, led to factional fighting and the formation of the SPLA-Mainstream (Torit Group, led by Garang) and the SPLA-United (Nasir Group, led by Machar). This split caused a major rift within the movement and thousands were killed and over 300,000 were displaced between 1991 and 1993. The rift between the two leaders was largely due to personal grounds and a contest for the control of the movement.

With the help of IGAD, the SPLA-Mainstream and the SPLA-United reached a consensus on two basic points as their negotiating positions with the Sudanese Government, namely self-determination for the Southern Sudanese and the Nuba Mountains, and a transitional period (Prendergast & Bickel 1994). Riek Machar and his group renamed the SPLA-United to the Southern Sudan Independence Movement (SSIM), which in 1997 amalgamated six factions into the United Salvation Democratic Front (USDF), established a military wing named South Sudan Defence Force (SSDF) and allied to Khartoum. The al-Bashir National Islamic Front Government also established a Coordinating Council for the Southern States (CCSS) and rewarded Machar by appointing him to head the body which has not thus far made any meaningful impact in the region.

IGAD’s role as the main peace broker has received continental and international recognition with the OAU, the United Nations and Friends of IGAD (who later re-conceptualised their role as IGAD Partners’ Forum, IPF) giving it more financial and political support. Apart from their support for IGAD’s peace process, Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW), and the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights (UNHCHR) have also proposed that international civilian human rights monitoring groups should be stationed in the affected areas to monitor the human rights violations by the Sudanese government and the liberation movements (Prendergast 1997:21). IGAD’s role has, therefore, been legitimised and internationalised with the support it receives from regional, continental and global state and non-state actors. The factional differences notwithstanding, the Southern and Nuba Mountains liberation movements generally agree on the objective of the separation of Religion and State and self-determination.

The issue of the Nuba Mountains and the Southern Blue Nile (SBN), given their geographic location in the North, are tricky issues for the SPLA/SPLM and other Southern liberation movements. The SPLA, with a quarter of its 60,000 army drawn from the Nuba, has insisted since 1985 that the area constitutes part of Southern Sudan because of its marginalisation by the regimes in Khartoum. A regional assembly was established in 1992 by the SPLM/SPLA to legislate on matters pertaining to the area under its control and to work closely with the SPLM’s Sudan Relief Rehabilitation Association (SRRA) in the delivery of humanitarian needs (De Waal 1999:1; Prendergast 1997:58). The Sudanese Government, however, maintains that the Nuba Mountains is part of the North and as such is not subject to any negotiations based on self-determination perspectives. On this issue, Sudan has received sympathetic support among the IGAD members, Egypt and the OAU in general. The OAU has remained conservative on the question of self-determination conceptualised within the context of re-drawing of the African states’ boundaries. The principle of uti possidetis institutionalised within the Charter of the OAU, in most cases, still carries the day.

Issues with regard to secular democracy

It needs to be emphasised that the issue of self-determination has not been the only negotiating position of the SPLM/SPLA and other liberation movements. The liberation movements’ original negotiating positions in the 1980s and early 1990s were based on the following perspectives: non-sectarian and non-theocratic states; united confederal states based on democracy, human rights and equality; and self-determination. These were the SPLM’s negotiating positions in the 1992 and 1993 Abuja (Nigeria) mediation. It is important to note that the inclusion of self-determination as a condition for the South and the Nuba liberation came as a result of the National Islamic Front (NIF) Government’s insistence on the adoption of sharia law, with the SPLM/SPLA stressing that self-determination is not to be viewed as synonymous with secession but as a choice between unity and secession. The imposition of sharia law by the regimes in Sudan has been the major stumbling block to the IGAD peace process since the 1980s (Adar 1998a, Adar forthcoming). The Abuja rounds did not yield any progress towards conflict resolution. During the 1994 IGAD peace negotiations in Nairobi, Kenya, the delegation from the Sudan Government reiterated the Government’s position by stipulating that “sharia and custom as they stand are irreplaceable”, stressing also that “legislation inspired by other sources are gauged and ratified according to the principles of sharia and custom” (Petterson 1999:131). These policy options by the SPLM/SPLA and the government in Khartoum were harmonised into the IGAD Declaration of Principles (DOP).

The IGAD Declaration of Principles

The 1994 IGAD Declaration of Principles stipulated some of the central elements of the negotiating viewpoints which have been suggested by a number of interested parties to the conflict over the years. The Declaration of Principles provide, among other things, that:

The right of self-determination of the people of South Sudan to determine their future status through a referendum must be affirmed … Maintaining of unity of Sudan must be given priority by all the parties provided that the following principles are established in the political, legal, economic and social framework of the country: Sudan is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural society. Full recognition and accommodation of these diversities must be affirmed … Extensive rights of self-determination on the basis of federation, autonomy … to the various peoples of Sudan must be affirmed. A secular and democratic state must be established in Sudan. (Horn of Africa Bulletin Sep-Oct 1994:27)

The DOP incorporated most of the negotiating positions of the Southern movements and in that light can be considered a triumph for the liberation movements, particularly for the SPLM/SPLA. The DOP also provided that the people of Sudan (North and South) had the right to determine their future through a referendum if the two parties fail to agree on the major principles contained in the Declaration.

Responses to the Declaration of Principles

The IGAD Declaration of Principles received a boost following its endorsement by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which is comprised of, among others, the SPLA/SPLM, the Umma Party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the Sudanese Communist Party (SCP), and the Legitimate Command led by Gen. Faithi Ahmed Ali, who are fighting against the NIF government of Bashir. Since then, the Government of Sudan has been under pressure from the northern and southern opposition movements to accept IGAD’s Declaration of Principles. The NDA endorsement of IGAD’s Declaration of Principles came as a result of the consensus which emerged at the end of the December 1994 Chukudum Accord between the Umma Party, led by former President Sadiq al-Mahdi (1985-1989), and the SPLA/SPLM, and was later reinforced by the 1995 Asmara Declaration of the NDA.

Most of the IGOs and NGOs operating in the Horn of Africa and Sudan in particular have endorsed the 1994 DOP promulgated by IGAD, thereby internationalising and legitimising its role. During their meeting with the UN Security Council members at their mission in Sweden, in November 1998, CARE International, Oxfam, Doctors without Borders, and Save the Children called on the UN to “generate a forceful and positive lobby for peace” and to “reinforce and complement the IGAD process” (Horn of Africa Bulletin Nov-Dec 1998:25-26). The IGAD peace process in Sudan has also received support from churches concerned with the humanitarian situation in the country and the Horn of Africa in general. At the end of their meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, church leaders from the Great Lakes and the Horn of Africa regions representing among others, the All African Conference of Churches (AACC), the National Council of Churches of Kenya (NCCK), and the New Sudan Council of Churches (NSCC) as well as observers from the SPLM and the Sudan Government declared their “recognition of IGAD as the primary forum for peace in Sudan based on the Declaration of Principles” (Horn of Africa Bulletin Mar-Apr 1998:27). The WCC affirmed its support for the IGAD DOP as the viable framework and the basis for a just and lasting peace in Sudan. At the end of the WCC Eighth Assembly meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, the delegates from Sudan stated in their press release that:

We call on the WCC to support the IGAD … peace initiative with the Declaration of Principles as the basis for resolving the Sudanese conflict. The WCC should not be party to the international conspiracy of silence on the genocide in Southern Sudan … The churches are in danger of showing the same indifference to the plight of Southern Sudan as they did to the plight of Jews under Hitler.

(WCC Press Release, no 34, 10 Dec 1998) Although the northern opposition parties such as the Umma Party and the DUP are sensitive to the idea of the secession of the South, they accept at least in principle, the right of the Southerners to hold a referendum on their future, which can lead to independence, provided that the separation can lead to the establishment of two friendly neighbouring countries (Lesch 1999:2). It seems that in retrospect Sadiq al-Mahdi (together with the Islamic-oriented parties in the NDA) has accepted that during his tenure as President of Sudan his Administration failed to accommodate the Southern question. Sadiq’s domestic policies did not deviate radically from those of Numeiri who had introduced the Islamic September laws prior to his overthrow by the military. The NDA’s endorsement of the Declaration of Principles may also be interpreted to mean that it is a mere tactic used by the Islamic parties within it to secure the SPLM/SPLA’s support to get rid of al-Bashir. Abandoning Islamisation programmes on a long-term basis is bound to encounter difficulties given the growing Islamic fundamentalism towards the centre in Sudan led by, among others, Hassan al-Turabi (Mahmoud 1997; An-Naim 1988; Warburg 1991).

The incorporation of Islamic laws into the 1998 Constitution of Sudan is a clear testimony to the importance attached to the Islamic movement towards the centre. The Constitution provides that Sudan is a unitary state wherein “people co-exist with their cultural diversity, Islam being the religion of the majority, while Christianity and other religions and doctrines are given due consideration inasmuch as there is no compulsion in religion” (Horn of Africa Bulletin Mar-Apr 1998:25). The Constitution also provides that sharia customary law (al-urf) and national consensus (ijma al-ummah) constitute the basis for legislation in Sudan. It is unlikely that the NDA, if it were to come to power, would overlook the growing internal Islamic movements, making the option of maintaining a unitary state in Sudan not viable, particularly for the SPLM/SPLA.

For most part of the 1990s the regime of al-Bashir rejected the IGAD Declaration of Principles, maintaining instead that any form of a referendum must take cognisance that the status of the Southerners is inseparable from the rest of Sudan. The government of Sudan is fearful that the implementation of the IGAD Declaration of Principles in toto may open up a pandora’s box for the rest of the country, particularly the Nuba Mountains and the SBN. Though in 1997 al-Bashir finally signed the peace process document incorporating the IGAD Declaration of Principles, his regime still maintains that the document is not legally binding on his government (Lesch 1999:3; Deng 1999:6).

Area linkages and tribal rivalries

The question of the Nuba Mountains and the SBN remains a difficult one for both the Sudan Government and the SPLM/SPLA. At the 1997 IGAD negotiations, the document presented by the SPLA/SPLM on the question of the Nuba Mountains and the SBN contained the following “separate but parallel” viewpoints: the right of self-determination alongside Southern Sudan, but separately; that the Southern Sudan, the Nuba Mountains and the SBN are to establish separate administrations during the transitional period; that the Southern Sudan, the Nuba Mountains and the SBN are to exercise their right to self-determination; and that the SBN and the Nuba Mountains are to demand regional self-determination which incorporates their socio-cultural, linguistic and religious ways of life (De Waal 1999:2).

The Nuba-SBN-South Sudan linkage was, however, moderated at the 1998 Addis Ababa IGAD negotiations by the Nuba-SPLA and SBN-SPLA commanders Yusuf Kowa Meklci and Malik Agar, respectively. Taking cognisance of the two regions’ incorporation into the larger South Sudanese proposals, the two leaders suggested that the Sudan Government should conclude the self-determination process with the South if the inclusion of Nuba and the SBN is the main obstacle. They, however, insisted that the right of self-determination and secession by the South would not prevent them from continuing with the liberation struggle in the North (Kuol 1999:2; Deng 1999:7). This decision was meant to close all avenues of intransigence on the part of the Sudan Government on the question of self-determination for the South.

The agreement reached in April, 1999 between the Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups, the Dinka and the Nuer, is likely to strengthen the liberation movements’ negotiating leverage vis-í -vis the Sudan Government. The meeting – funded by USAID – which led to the Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Covenant, as the pact was dubbed, was brokered by the New Sudan Council of Churches and signed by over 300 chiefs from both sides in the presence of the SPLA commander Salva Kiir (a Dinka from Gogrial region) and the Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Rumbek, Monsignor Caesar Mazzorali (Horn of Africa Bulletin Mar-Apr 1999:23). The Dinka-Nuer rapprochement is bound to have positive and negative impacts on the SPLM/SPLA and the Sudan Government, respectively. More importantly, however, at least for the SPLM/SPLA, is that it is going to weaken the base of Riek Machar and USDF and SSDF as well as Lam Akol’s SPLA-United, both of whom are already experiencing a rift from within their ranks and a mistrust by the Sudan Government. The agreement will reduce pressure on the SPLA forces and as such help their military strategists to redirect their efforts towards the Sudanese Popular Defence Forces (SPDF) and the People’s Defence Forces (PDF), estimated to be more than 100,000 and 150,000, respectively.

For decades, the Sudan regimes have exploited the Dinka-Nuer ethnic rivalries to weaken the Southern movements, particularly the SPLA. Apart from this intra-ethnic conflicts the SPLA has also been engaged in military conflict with the Sudan Government instigated militias called murahalin, drawn mainly from the cattle raising Baggara Arabs (Rizeiqat, Rufaa al Huj, and Misiriya) in Darfur and Kordofan areas, particularly in the late 1980s and 1990s (Bradbury 1998). Sudan also supports other militias against the SPLA as well as giving material and logistical support to some militias against countries in the IGAD region and in other parts of the continent. Apart from giving support to the murahalin and the SSIM, Sudan also provides logistical and material help to the Lotohus, the Toposas, and the Mandaris operating in Equatoria, Kenyan-Sudanese border, and Terakeka (north of Juba), respectively. These militias were supplied with intelligence, landmines, and other arms, particularly G-3s, Kalashnikovs, mortars, and light machine guns.

The Dinka-Nuer agreement already discussed is likely to reduce risks involved in carrying out humanitarian operations to help millions of the war victims, let alone victims of 500,000 to 2,000,000 land mines laid in Sudan, mostly in the South (Horn of Africa Bulletin Sep-Oct 1994:34). The increasing involvement of IGOs and NGOs on matters pertaining to humanitarian concerns and conflict resolution is an added incentive to IGAD. The experiences of the 1991-93 Dinka-Nuer conflicts concentrated around Ayod, Waat and Kongor towns, dubbed the “Starvation Triangle”, which claimed over 20,000 lives and reduced NGO operations, may never re-occur (Prendergast 1997, Rone & Prendergast 1994). In such war torn areas the internal NGOs, for example, the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Association (SRRA), the Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC, Sudan Government’s Humanitarian arm), the NSCC, and the Relief Association of Southern Sudan (RASS, Machar’s SSIM humanitarian wing) as well as the international IGOs and NGOs, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), World Vision Centre of Concern, CARE International, the Sudan’s Red Crescent (SRC), Save the Children, Oxfam, and Doctors without Borders, among others, have been instrumental in providing humanitarian assistance as well as conflict resolution initiatives.

The US also provides substantial humanitarian assistance to the war ravaged country, Sudan. In conjunction with other agencies, the USAID’s Regional Economic Development Services Office for East and Southern Africa (REDSOESA) serves as a base for the Clinton Administration’s mechanism for food security, sustainable economic growth and conflict prevention strategies in the area (USAID 1999). The US humanitarian support for Sudan has also been directed through the UN-led Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) and some of the NGOs operating in war affected areas. In 1995, for example, the US gave over $30 million and $2.8 million in aid to the USAID and OLS, respectively, for humanitarian efforts in Sudan. Between 1989 and 1998 the US gave humanitarian assistance of over $750 million to Sudan, with over $110 million disbursed in 1998 alone.

Armed forces and military spending

As Table Two indicates, Sudan ranks second to Ethiopia in its armed forces and military spending. The figures for the armed forces for the Sudan exclude the PDF. In 1994 alone Sudan spent over $400 million in military procurement. Sudan’s military expenditure increased markedly, particularly after the military takeover in 1989. Since then, the Government of Bashir continues to spend more the $1 million per day in the war efforts against the rebel movements in the South. Table Two shows that unlike some of the members of IGAD, Sudan’s armed forces have also increased steadily since the late 1980s. The figures for Sudan do not include the PDF established by the Bashir regime to augment the SPDF. Whereas the SPLA exchange timber, cattle, animal trophies for weapons, the Sudanese Government relies on oil and mineral production for its military expenditure. The increased production of oil is not only going to harden the negotiating position of the Sudanese Government vis-í -vis the liberation movements but it will stagnate IGAD’s peace process.

Oil and mineral production in Sudan have attracted a number of prospectors such as Qatar’s Gulf Petroleum Corporation, Russian state-owned YUKOS and Zarubezh-neftegasstroi, a Canadian firm, Talisman Energy, Malaysia’s Petronas Carigali, Chinese National Petroleum Company, and Sudan’s National Oil Company (Adar 1998a; Field 2000; Africa Confidential 1995:4). The Greater Nile Oil Project (GNOP), established and owned by China National Petroleum Company (40%), Malaysian Petronas Carigali (30%), Talisman Energy (25%), and Sudapet-Sudan National Oil Company (5%), is responsible for most of the production of oil in the country (Field 2000). The NIF Government permitted Arakis Energy (later bought by Talisman Energy in 1998) to hire Executive Outcomes of South Africa to protect its oil fields near Bentiu. Crude oil is transported from Hijleij (West Kordofan) and southern Darfur to Port Bashir, south of Port Sudan by Chinese, Argentinean and British companies. The other operating oil fields are at Adar, Western Upper Nile, and Unity, Unity State (Field 2000). Apart from oil, the French, Chinese, and South African mineral companies have also entered the Sudanese market for gold prospecting, with a Franco-Sudanese firm, ARIAB, taking the lead in gold mining.

4. Summary of negotiating positions of Sudanese goverments and rebel movements

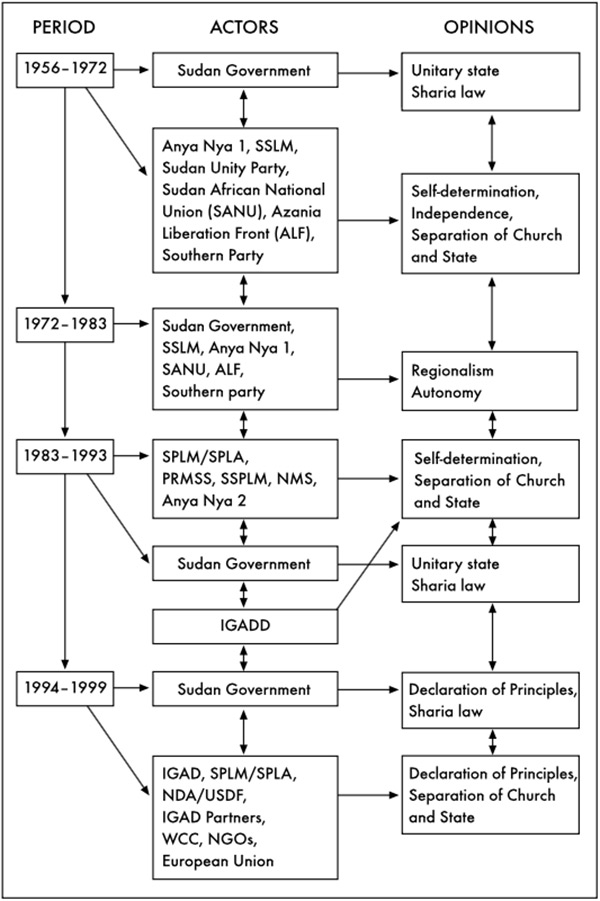

The challenges which IGAD has encountered in its peace process in Sudan are enormous and persistent. Figure One demonstrates the consistency and change with respect to the negotiating positions of the Sudanese Governments and the rebel movements over the years, particularly between 1956 and 1999. As the Figure indicates, the central negotiating position by the Sudanese authorities over the years has been that of retaining a theocratic Islamic unitary state based on sharia laws. The rebel movements, on the other hand, have championed the idea of the separation of church and state, autonomy and self-determination.

Table 2. Armed forces and Military expenditure of IGAD members, 1985-1995

| Armed Forces (Thousands) | |||||||

| Year | Djabouti | Ethiopia | Eritrea | Kenya | Somalia | Sudan | Somalia |

| 1985 | 4 | 240 | NA | 19 | 43 | 65 | 15 |

| 1986 | 4 | 300 | NA | 20 | 50 | 59 | 15 |

| 1987 | 4 | 250 | NA | 21 | 50 | 59 | 25 |

| 1988 | 4 | 250 | NA | 20 | 47 | 65 | 35 |

| 1989 | 4 | 250 | NA | 20 | 47 | 65 | 40 |

| 1990 | 4 | 120 | NA | 20 | 47 | 65 | 60 |

| 1991 | 3 | 120 | NA | 20 | NA | 65 | 60 |

| 1992 | 8 | 120 | NA | 24 | NA | 82 | 70 |

| 1993 | 8 | 120 | NA | 24 | NA | 82 | 70 |

| 1994 | 8 | 120 | NA | 22 | NA | 82 | 60 |

| 1995 | 8 | 120 | NA | 22 | NA | 89 | 52 |

| Military Expenditure ($ Million) | |||||||

| Year | Djibouti | Ethiopia | Eritrea | Kenya | Somalia | Sudan | Uganda |

| 1985 | NA | 252 | NA | 122 | NA | 146 | 63 |

| 1986 | 44 | 264 | NA | 127 | 33 | 128 | 89 |

| 1987 | 49 | 305 | NA | 158 | NA | 197 | 189 |

| 1988 | 52 | 397 | NA | 213 | NA | 245 | 77 |

| 1989 | 36 | 468 | NA | 162 | 14 | 280 | 78 |

| 1990 | 41 | 542 | NA | 198 | 9 | 204 | 92 |

| 1991 | 49 | 409 | NA | 195 | NA | 531 | 131 |

| 1992 | 46 | 164 | NA | 209 | NA | NA | 101 |

| 1993 | 31 | 145 | NA | 179 | NA | NA | 80 |

| 1994 | 27 | 132 | NA | 151 | NA | 436 | 73 |

| 1995 | 22 | 118 | NA | 173 | NA | NA | 126 |

Source: US Department of State 1998

Figure 1. Conflict in Sudan and actors’ opinions on the Southern Sudan questions, 1956-1999

Originally, Sudan regarded the civil war as an internal matter and was not willing to negotiate its own sovereignty. However, over the years, particularly in 1972 and 1990, Sudan officially expressed a willingness to discuss with third parties matters pertaining to its internal affairs. As Figure One indicates, for the first time, the NIF led Government accepted, in principle, the idea of the separation of church and state inscribed in IGAD’s Declaration of Principles. However, it is important that we make some observations with respect to the various viewpoints which are still linked to the parties in the conflict. For example, the SPLM/SPLA accepts the idea of a unitary state provided there is a complete separation of church and state, equality for all the Sudanese to be incorporated in the Constitution and equal sharing of wealth. The Umma Party on the other hand supports a decentralised system during the transition period, with special status to Southern Sudan and thereafter an envisaged vote for unity. In other words, autonomy of the South, according to the Umma Party, would encourage the South to accept unity.

Conclusion

An emerging consensus

The situation in the Sudan is a complex one. It has attracted many state and non-state actors with interlocking interests. Ever since its creation IGAD has brought the parties to conflict in Sudan to a point where they have accepted, at least in principle, the option of self-determination for the South. This is obviously an achievement on the part of the Organisation, given the turbulence in Sudan and the region in general. The transformation of IGAD into an IGO responsible for conflict resolution, prevention and management has given the organisation incentives on the Sudanese peace process. It is fair to argue that a consensus is emerging among the belligerents with respect to the option of self-determination for the South. Apart from the other pertinent issues that I have discussed, the other areas of disagreement between the Sudan Government and the SPLM/SPLA include the right boundaries of the South. The SPLM/SPLA insist that self-determination is to apply to the district of Abyei Dinka, Nuba Mountains, and South Blue Nile, areas considered to be culturally and historically part of the South. For IGAD to succeed in maintaining the consensus which is emerging, a number of factors need to be taken into account.

Recommendations and warnings

- First, a coalition of IGAD-OAU-UN peacekeeping force based on the “US/NATO” model, with prior consent of the parties, is needed to maintain the emerging consensus. The peacekeeping force must be given a broad mandate including peacemaking, and it should have the ability to disarm and demobilise the parties to the conflict.

- Second, a referendum for the South and other marginalised areas should remain an option for the affected areas. It will have to be supervised by an international monitoring team.

- Third, there is a need for shuttle diplomacy, perhaps similar to the Henry Kissinger-Lee Doc Tho diplomacy of the 1970s which ended the Vietnam War, comprising experts appointed by IGAD, the OAU, League of Arab States, Organization of Islamic States (OIS), and the UN to speed up the peace process. This can be done by way of the appointment of special envoys to IGAD to enhance the peace process and to deal with humanitarian issues in conjunction with IGAD. The OAU and the UN bodies need to take a more active role in the IGAD peace process, particularly given that Sudan has accepted, in principle, the DOP.

- Fourth, the UN’s pro-active involvement in the peace process would help in the monitoring of the situation and the imposition of an arms embargo against parties that do not adhere to the agreement.

- Fifth, IGAD should involve all the belligerents in the peace process irrespective of their political affiliation. The more inclusive the peace process, the more likely that it would have a long lasting peace impact in the area.

- Sixth, the IPF and other interested parties need to develop coherent and co-ordinated policies based on long term objectives, for example, post-settlement aid for reconstruction, debt relief, investments, and trade.

The initiatives by Egypt and Libya on the peace process in Sudan, while well intentioned, may instead harden the SPLA position. Libya and Egypt are, at the bilateral levels, banking on convincing the NDA to cease hostilities and negotiate a peaceful settlement to the conflict in Sudan. There is a paradox in the way the world is merely watching while the Sudanese state continues to be criminalised by those who purport to be speaking on behalf of their peoples. The level at which the state is criminalised is taking a new dimension, with the NIF led Government with its full knowledge and acquiescence re-introducing slavery.

Promising co-operation

The concerted efforts and direct initiatives of the civil society, particularly the women’s bodies such as the Nuba Women’s group and the Southern Women’s group working across the ethno-centric and religio-cultural divides with their northern counterparts, as well as the NSCC, are steps in the right direction that deserve incentives from all those concerned with democracy and human rights. The 1998 Wunlit Covenant has laid the foundation for frequent consultations among the Nuers and Dinkas both at the official and the grassroots levels culminating into what has become known as the Nuer-Dinka Loki Accord. The UN, OAU, and more so IGAD, can build on these initiatives to enhance confidence among the belligerents.

Sources

- Adam, H.M. 1995. Somalia: A Terrible Being Born? in Zartman, I.W. (ed) Collapsed States: The Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority, 69-89. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Adar, Korwa G. 1994. Kenyan Foreign Policy Behaviour Towards Somalia, 1963-1983. Lanham: University Press of America.

- Adar, Korwa G. 1998a. A State Under Siege: The Internationalisation of the Sudanese Civil War. African Security Review 7(1), 44-53.

- Adar, Korwa G. 1998b. From Nations to Nation State to Nations: The Withering Away of Somalia. Politics, Administration and Change, 30 (Jul-Dec), 30-47.

- Adar, Korwa G. Forthcoming. Islamisation and the Sudanese Civil War: The Fallacy of the Sudanese Policy of National Identity, in Toggia, Pietro, Lauderdale, Patrick & Zegeye, Abebe (eds), Terror and Crisis in the Horn of Africa: Autopsy of Democracy, Human Rights and Freedom. Ashgate: Aldershot.

- Africa Confidential 9 Jun 1995, 36(12), 4.

- Africa Confidential 7 Jul 1995, 36(14), 2-3.

- An-Naim, A.A. 1988. Constitutionalism and Islamism in the Sudan, in The International Third World Studies: Building Constitutional Orders in Sub-Saharan Africa, 99-118. Valparaiso, IN: International Third Word Legal Studies Association and the Valparaiso University School of Law.

- Anyang’ Nyong’o, P. 1991. The Implications of Crises and Conflicts in the Upper Nile Valley, in Deng, F.M. & Zartman, I.W. (eds), Conflict Resolution in Africa, 95-114. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

- Avruch, K. & Black, P. 1991. The Culture Question and Conflict Resolution, Peace and Change 16, 22-45.

- Bakwesegha, C.J. 1994. Forced Migration in Africa the OAU Convention, in Adelman, H. & Sorenson, J. (eds), African Refugees: Development Aid and Repatriation, 3-18. Boulder: Westview.

- Bradbury, M. 1998. Sudan: International Responses to War in the Nuba Mountains, Review of African Political Economy 77 (25) (Sept), 463-474.

- Buzan, B. 1983. People, States and Fear: The National Security Problem in Internal Relations. Brighton: Wheatsheaf.

- Clapham, C. 1997. Africa and The International System: The Politics of State Survival. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cleary, S. 1997. The Role of NGOs Under Authoritarian Political Systems. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Deng, F.M. 1995. Mediating the Sudanese Conflict: A Challenge for the IGADD, CSIS Africa Notes, No. 169 (Feb), 1-7.

- Deng, F.M. 1999. Sudan Peace Prospects at a Cross-Roads: An Overview. USIP Consultation on the Sudan, Washington, D.C., 14 Jan, 1-12.

- Deng, F.M. et al. 1996. Sovereignty as Responsibility: Conflict Management in Africa. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

- Deng, F.M. & Gifford, P. (eds) 1987. The Search for Peace and Unity in Sudan. Washington, D.C.: The Wilson Press.

- Denyer, S. 1999. UN Probes Claim Sudan Used Chemical Weapons. Reuters, Nairobi (2 Aug).

- De Waal, A. 1999. The Road to Peace in Sudan: Prospects for Pluralism in Northern Sudan.

- USIP Consultation on Sudan, Washington, D.C., 14 Jan, 1-6. Ethiopian Herald, 11-12 Apr 1998.

- Field, Shannon 2000. The Civil War in Sudan: The Role of the Oil Industry. Johannesburg: Institute for Global Dialogue. (IGD Occasional Paper No. 23.)

- Fisher-Thompson, J. 1999. US Senate to Consider Bill to Push Peace Process In Sudan. USIS Washington File, 27 July.

- Horn of Africa Bulletin. 1994. 6(5) (Sept-Oct), 26-35. Horn of Africa Bulletin. 1998a. 10(2) (Mar-Apr), 24-34. Horn of Africa Bulletin. 1998b. 10(6) (Nov-Dec), 21-35. Horn of Africa Bulletin. 1999. 11(2) (Mar-Apr), 23-35.

- Horn of Africa: The Monthly Review, 1998. (April-May), 1-14. IGAD 1996. Food Situation Report No. 2/96. Djibouti. IGAD.

- IGAD 1998. Declaration of the 17th Session of the Council of Ministers of IGAD on the Conflict Situation in the Sub-Region. Djibouti: IGAD (15 Mar).

- IGAD 1999. Programme on Conflict Prevention, Resolution and Management. Djibouti: IGAD. Kuol, D.A 1999. Notes on the Peace Process in Sudan.: USIP Consultation on Sudan, Washington, D.C., 14 Jan, 1-8.

- Kibreab, G. 1994. Refugees in the Sudan: Unresolved Issues, in Adelman, H. & Sorenson, J. (eds), African Refugees: Development Aid and Repatriation, 43-68. Boulder: Westview.

- Lesch, A. 1999. Consultation on Sudan. USIP Consultation on Sudan, Washington, D.C., 11 Jan, 1-8.

- Lynch, C. 1999. UN Unit Seeks Sudan Chemical Weapon Probe. Washington Post, 3 Aug, A12. Lyons, T. 1995. Great Powers and Conflict Reduction in the Horn of Africa, in Zartman, I.W. &

- Kremenyuk, V.A. (eds), Cooperative Security: Reducing Third World Wars, 241-266. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Lyons, T. 1996. The International Context of Internal War: Ethiopia/Eritrea, in Keller, E.J. & Rothchild, D. (eds), Africa in the New International Order: Rethinking State Sovereignty and Regional Security, 85-99. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Magyar, K.P. & Conteh-Morgan, E. (eds), 1998. Peacekeeping in Africa: ECOMOG in Liberia. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Mahmoud, M. 1997. Sufism and Islamism in the Sudan, in Rosander, E. E & Westerlund, D. (eds), African Islam and Islam in Africa, 162-192. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Midlarsky, M.I. (ed) 1992. The Internationalization of Communal Strife. New York: Routledge.

- Nyango’ro, J.E. & Shaw, T.M. 1998. The African State in the Global Economic Context, in Villalon, L.A. & Huxtable, P.A. (eds), The African State at a Critical Juncture: Between Disintegration and Reconfiguration, 27-42. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Petterson, D. 1999. Inside Sudan: Political Islam, Conflict, and Catastrophe. Boulder: Westview.

- Prendergast, J. 1997. Crisis Response: Humanitarian Band-Aids in Sudan and Somalia. London: Pluto Press.

- Rone, J. & Prendergast, J. 1994. Civilian Devastation: Abuses by All Parties in the War in Sudan. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Shaw, T.M. 1995. New Regionalism in Africa as Responses to Environmental Crises: IGADD and Development in the Horn in the Mid-1990s, in Sorenson, J. (ed) Disaster and Development in the Horn of Africa, 249-263. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Shaw, T.M. & Okolo, J.E. (eds) 1994. The Political Economy of Foreign Policy in ECOWAS. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Simons, A. 1995. Networks of Dissolution: Somalia Undone. Boulder: Westview Press. UNEP 1996. Report of the Regional Consultations Held for the First Global Environment Outlook. Nairobi: UNEP.

- US Department of State 1995. Testimony: E. Brynn on US Policy Toward Sudan. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of African Affairs.

- US Department of State 1998. World Expenditures and Arms Transfers, 1996-1997. Washington, D.C.: Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.

- USAID 1994. African Disaster Response, African Bureau Office of Disaster Response Coordination and Office of Sustainable Development, Private Sector Growth and Environment Division. Washington, D.C.: USAID.

- USAID 1995. USAID Office of Food for Peace. Washington D.C.: USAID.

- Warburg, G. 1994. The Sharia in Sudan: Implementation and Repercussions, in Voll, J.O. (ed) Sudan: State and Society in Crisis, 90-107. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Winter, R. 1999. Sudan’s Humanitarian Crisis and the US Response. US Committee For Refugees, Testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Subcommittee on African Affairs, 23 Mar.

- World Council of Churches 1998a. Nations Must Stop the Slaughter in Sudan, WCC Eighth Assembly, Press Release no. 10, 5 Dec.

- World Council of Churches 1998b. WCC Must Not be Party to Conspiracy of Silence on Genocide, Press Release, no. 34, 10 Dec.

- Zartman, I.W. 1995a. Collapsed States: The Disintegration and Restoration of Legitimate Authority. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

- Zartman, I. W. 1995b. Inter-African Negotiation, in Harbeson, J. & Rothchild, D. (eds), Africa in World Politics: Post-Cold War Challenges, 209-233. Boulder: Westview Press.