Abstract

How does the 2020–2022 civil war in Ethiopia contribute to our understanding of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine? This study seeks to revisit the debate over the effectiveness of the R2P doctrine in the wake of increased intrastate conflicts. The objective is to assess the dilemma that arises with the implementation of R2P when governments are involved in the conflict and the international community is reluctant or unable to intervene. The study adopts the systematic review approach (PRISMA) to identify the shortcomings, trends, and debates around R2P. It uses the Ethiopian civil war to contribute further to the existing body of literature. The paper finds that, indeed, the R2P doctrine is facing serious challenges with its implementation. It shows that when governments fail to acknowledge the other actors as legitimate combatants and instead describe them as terrorist groups, it becomes difficult to uphold the R2P doctrine. The paper also identifies a lack of leadership and coordinated efforts at regional and international levels as contributing factors, which further undermine the effectiveness of R2P. The paper concludes that the Ethiopian civil war exposes serious shortcomings in the R2P doctrine that need to be reviewed and reformed urgently. It proposes the adoption of a systems-thinking approach that can streamline the actors and processes of response during civil wars.

Introduction

The adoption of the R2P doctrine was received with both excitement and scepticism among policy makers and researchers alike (Newman, 2013; Junk, 2016; Bellamy, 2022). Researchers have sought to examine the impact of R2P on, among other issues, conflict resolution, state sovereignty, and humanitarian interventions (Martin, 2011; Zimmerman, 2022; Berg, 2022). At the core of these studies was the occurrence of mass atrocities which were witnessed during conflicts in places like Srebrenica and Rwanda in the 1990s. It sparked the need to develop a framework that would address the obstacles that hindered international interventions in countries where governments were unable or unwilling to protect civilians during a conflict.

The ideas of non-interference and sovereignty had emerged during the Treaty of Westphalia. At the time, they were seen as the underlying reason for the inaction by international and regional actors with regard to the domestic affairs of other countries (Cohen and Deng, 2016). Nonetheless, the horrors of genocide and other war-related atrocities motivated the International Committee on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) to recommend the R2P doctrine in 2001. It was later overwhelmingly ratified by states during the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in New York in 2005. Proponents viewed this as a unique way of preventing the kind of tragedies that had characterised the conflicts in Srebrenica and Rwanda.

This is because the R2P doctrine states that “(1) sovereign states have a responsibility to protect their population against genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and ethnic cleansing; (2) the international community should help individual states to live up to that responsibility, and; (3) in those cases where a state is incapable or unwilling to protect its citizens, other states have a responsibility to act promptly, resolutely and in compliance with the UN Charter” (Thakur and Weiss, 2009).

However, since the ratification of the R2P doctrine, its implementation has faced an uphill task and, in many instances, has come under criticism. The Arab spring that had spread across North Africa and the Middle East allowed both proponents and opponents of the R2P doctrine to reflect on their positions. For example, the intervention in Libya (Nuruzzaman, 2022; Kul, 2022), which had a tragic result, gave the opponents of R2P some basis to strengthen their view of non-interference and sovereignty. At the same time, it gave proponents of R2P reasons to rethink and build consensus on how the doctrine could be best reformed. The purpose would be to ensure its longevity and acceptance in the long term (Wamulume et al., 2022; Pison, 2022).

Furthermore, R2P’s effectiveness has also come into question during the conflicts in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan, and other parts of the world (Nyadera, 2018; Nyadera et al., 2023). This has sparked a serious debate on whether R2P is capable of achieving some of the objectives it has set out to achieve. The grounds upon which R2P was established remain solid and even opponents cannot overlook its importance in ensuring the protection of civilians during conflicts. However, some of the concerns that have emerged relate to the abuse of the R2P doctrine by states seeking to promote their own interests. In addition, there are other normative questions that remain problematic. These include the criteria and timing of interventions, accountability when such interventions worsen the situation, and the issue of whose responsibility it is to intervene (Murray, 2012; Zähringer, 2021; Pedersen, 2021). The challenges facing the implementation of R2P continue to emerge with the conflict in Ethiopia.

The conflict in Ethiopia between the government and Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) has been a key cause of concern for policymakers and researchers. This is because of the devastating impact it continues to have on the civilians. It is also because of the timing given the ravaging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and how that exacerbates the suffering. Despite emerging literature on the conflict, there has been limited attention directed towards a much bigger question that has the potential of challenging the effectiveness of some international norms and doctrines. In this particular conflict, the challenging question arising is whose responsibility it is to protect civilians during the war? The R2P doctrine is clear on the government’s responsibility to protect its citizens from potential genocide. However, certain factors pose a difficult challenge in the implementation of the R2P doctrine. These include crimes against humanity, extrajudicial killings, ethnic cleansing and war crimes, the asymmetric nature of this conflict as well as the actors involved. Indeed, such complexities are not unique in Ethiopia.

The crisis in Syria, the war in Libya, and the catastrophe in Yemen can all be understood from this lens. It has been two decades since the R2P doctrine was adopted. It seems to be facing immense challenges domestically where the government does not want to acknowledge that there is a conflict that can lead to mass atrocities. It also faces international challenges where power play within the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) undermines decisions on humanitarian intervention (Lepard, 2021; Welsh, 2021).

With civilians caught up between the government and TPLF forces, the risk of atrocities and war crimes being committed against civilians by both parties increases substantially. Even more importantly, some of the government response measures and narratives such as requesting civilians and other international actors (such as Eritrea) to join its efforts against the TPLF signal problems. It not only signals the complexity of the conflict but also the danger of mass atrocities being committed.

The motivation to carry out this study is to examine the complexities of the conflict and propose a systems-thinking approach as an alternative framework. Such a framework can integrate regional organisations into the R2P doctrine creating a new layer of actors who can respond should the government and the international community fail to act on time. While both parties to the conflict have been blamed for committing atrocities and war crimes, it is the weaknesses of existing conflict analyses, resolutions, and management frameworks that call for reforms.

The Ethiopian civil war is not only a timely case study to examine, but it also has clear characteristics that would necessitate the activation of the R2P doctrine. Indeed there is a threat posed to civilians by both parties and there is an inability/lack of commitment by the government to protect civilians in areas where the government experiences opposition. This justifies the choice of this particular civil war.

The paper then examined reports on the nature and intensity of the violence. It used this information to question why the government of Ethiopia has not lived up to the expectations of domestic and international norms as prescribed under R2P. It also assessed the reasons for the slow humanitarian intervention in Ethiopia, given the international obligation to react whenever governments fail to protect their citizens. In the case of Ethiopia, the civilians and government are engaged in a war. This creates a situation where the government is required to protect its adversaries. The author then examined the gaps in the R2P doctrine and recommended alternative approaches. Such approaches will help to strengthen the responsibility to protect especially in instances where the government is part of the conflict. The study will generate policy recommendations.

Ethiopia in Context

According to the World Bank (2022), Ethiopia’s population as of 2020 was approximately over 115 million people – making it the second-largest country in Africa in terms of population after Nigeria and above Egypt. This population is constitutive of more than 80 ethnic groups, thereby making Ethiopia a multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic, and multi-religious society. However, four ethnic groups namely, the Oromo (35%), the Amhara (26%), the Somali (6.2%), and the Tigre (6%) constitute approximately two-thirds of the total population (Fessha, 2022). Freedom House, an independent democracy watchdog organisation established in 1941, categorises Ethiopia in its 2022 Democracy Index as a “not free state” (Freedom House, 2022). The organisation uses measures such as rule of law, freedom of expression, association and belief, and the rights of women, minority groups, and marginalised groups. Such a low score for Ethiopia can partly be because of turbulent political developments and the conflict between the central government and the security forces in the Tigray Region. In terms of its political structure, more than 13 regional states collectively make up the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Some of them include: Afar; Amhara; Benishangul-Gumz; Gambella; Harrari; Oromia; Somali; Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples (SNNP); and Tigray. All of these constitute the national regional states, while Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa are categorised as city administrations.

The regional states operate as semi-autonomous entities with a significant level of self-rule. They are comprised of: regional councils; the executive administration; the constitution; the regional language (used in courts, schools, and public offices); the flag; and the authority to prepare and approve budgets and economic development programmes (Zewde et al., 2002). Despite the constant political problems facing the country, there have been improvements. Ethiopia has recorded significant economic growth and reduction in the levels of absolute poverty as well as improved access to social services such as healthcare and education. Between 2000–2009, the gross domestic product (GDP) expanded by an average of 8.44%, whereas between 2010–2019, GDP grew by an average of 9.27% (Katema and Diriba, 2021). The African Development Bank puts Ethiopia’s GDP growth for 2022 at 4.9%. This is while the World Bank puts the number at 5.6% and the International Monetary Fund puts the country’s GDP growth for 2022 at 6.1%. Despite the varying figures with regard to growth, the trend indicates that the country’s GDP growth is on a positive trajectory.

Historical Background of the Conflict

The Constitution of 1995 was created in an attempt to address the complexities of a multi-ethnic society by allowing Ethiopia’s diverse ethnic groups some element of cultural, economic, and linguistic autonomy. It also sought to rectify Ethiopia’s historical imbalances with regard to political power. However, the Constitution has had unintended consequences that overshadowed the original constitutional promise. The shortcomings within the Constitution of 1995, for instance, played a key role in shaping contemporary conflict dynamics by institutionalising ethnic politics (Bayu, 2022). Not only did it divide regional governments along ethnonational identities, but it also granted the right to secession and self-determination to the “nations, nationalities, and peoples” of Ethiopia (Abdullahi, 1998). The Constitution of 1995 has therefore replaced the general sociological notion of a state existing as a nation, with a new idea of Ethiopia existing as a ‘nation of nations’. Ethnonationalism has therefore evolved to occupy the centre of domestic politics and, with it, a political culture of ethnonational competition and regional hostilities. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) capitalised on ethnonational politics as a political currency, so much so that its policies produced even further sentiments of marginalisation across different ethnic groups.

The lack of inclusivity and consultations in its approach to governance had begun to brew tensions between the federal government and some ethnic groups such as the Oromo. The Oromo historically fought against the federal government and the political domination of the Amhara during the imperial era. For example, in 2014, the federal government developed the Addis Ababa Master Plan. The plan sought to extend the geography of the capital city into the Oromia territory and, in the process, displace thousands of Oromo farmers (Záhořík, 2017). The clash between protestors and the federal government, motivated some political players to use the Oromia grievances to push for an insurgency. These clashes led to the death of hundreds of civilians and many more others who were arrested and imprisoned. Although the government abandoned this plan, it was too little too late as protests had quickly spread to other regions. Also, protestors picked up on other grievances such as the demand for the respect of human rights and freedoms, economic justice, and better representation (Dias and Yetena, 2022). What these nation-wide protests managed to achieve in the long run was that Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn (2012–18) ultimately resigned following internal party pressure from the EPRDF politburo. This paved way for Abiy Ahmed’s transition into power as the prime minister in 2018.

Emboldened to take action and address the grievances that the protestors had raised, and which had led to the resignation of his predecessor, Abiy embarked on an ambitious reform agenda. As an Oromo himself, his appointment to the position of prime minister was received with great enthusiasm. This was because of his youthful exuberance. It was also because the Oromo ethnic group hoped that their political marginalisation in Ethiopian politics, which had been dominated by Tigrayan elites, had finally come to an end. Keeping up with the wave of public support, Abiy took certain actions which included: the release of thousands of political prisoners; the lifting of restrictions on freedom of the press and expression; the support of Sahle-Work Zewde (a female) for president; the establishment of gender parity in the cabinet; the signing of a peace agreement with the Oromo Liberation Front; and inviting exiled Ethiopian opposition political leaders back to the country (Ylönen, 2018). To crown these reforms, within less than two years since coming to power, Abiy won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize. This was for his role in the establishment of a peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea. The agreement put an end to a conflict stalemate that had spanned two decades after the 1998 border dispute. However, these reforms were quickly overtaken by the deterioration of elite political relations. Also, the hope and stability that was engrained at the beginning of Abiy’s political term quickly evolved into real concerns for a protracted civil war and a biting humanitarian crisis. But what underlying factors were responsible for this unprecedented change that led to violent conflict in Ethiopia’s social and political dynamics?

Characteristics of the 2020 Ethiopian Civil War

In November 2020, conflict broke out between the federal government and groups categorised as rebels. These rebel groups are mainly drawn from and affiliated with the TPLF. In the beginning, the conflict was presented as a swift security operation response by the federal government. However, it ultimately developed into a protracted conflict involving the Ethiopian military forces and the Eritrean military forces who support the Ethiopian forces. The immediate cause of the escalation of political tensions into military warfare was an outcome of a pre-emptive attack on Ethiopian military bases by the TPLF in Tigray. The TPLF cited that the attack was anticipatory self-defence against the military build-up by the Ethiopian Defence Forces that was reportedly going on around the Tigray region. At one point in time, significant gains by the TPLF saw it establishing complete military control in Tigray before launching attacks on other regions. These regions include Amhara, Afar, and a march towards the capital city of Addis Ababa – coming as close as 380 kilometres from the city. In response, the federal government declared a state of emergency and embarked on a programme of conscription of youths and retired military personnel loyal to the federal government. The purpose was to counter the incursion by Tigrayan forces towards the capital (Salemot, 2021; Abbink, 2022).

These efforts significantly transformed the battleground in favour of the federal government who managed to push the TPLF forces back to the mountains of Tigray. However, as is with all cases of wars and violent conflicts, these clashes had far-reaching impacts. According to Ghosh (2022), the Ethiopian civil war has left many people dead, and many others exposed to starvation, while properties and land have also been lost in the process. This war is one of the worst the country has experienced in decades. The federal government has been accused of playing a significant role in the number of civilian casualties who starved to death. This was because they as the government prevented the delivery of humanitarian aid. However, the Tigrayan forces have equally been accused of rape, looting, and the murder of the Amhara and Afar groups.

Immediate causes of the conflict

While there are varying immediate causes that triggered the violent conflict in Ethiopia, this paper examines a number of them. First, the unilateral political decisions and reforms initiated by Abiy were not broadly welcomed across the political divide. It was in particular not welcomed among the Tigrayans who evaluated such actions as exclusive and an attempt by the prime minister to centralise power. It is imperative to recognise that the TPLF was established as a political party with a Marxist–Leninism ideological orientation – one that strongly despises political centralisation in favour of political decentralisation. Therefore, three things triggered the TPLF’s fear that Abiy was attempting to centralise power, weaken regional governments, and establish personal rule. These include: key decisions by Abiy’s government to indefinitely postpone elections in the name of public health preventive measures against COVID-19 in 2020; the disbandment of the EPRDF as a coalition and; the merger of its constitutive regional political parties into the Prosperity Party. As a sign of defiance, the TPLF regional government in Tigray held its own elections in 2020 against the directives and guidelines of the

federal government. It thereby influenced the Ethiopian parliament to take

a historic vote that culminated in the decision to cut ties between the federal government and leaders from the Tigray region.

Second, the crisis within the EPRDF also had an impact on the outbreak of the conflict. The EPRDF coalition had been on the periphery of power in Ethiopia until 1991 when it formed a government. The TPLF was a key player in the coalition and dominated governance in Ethiopia for over three decades. Members from the TPLF were in control of critical government institutions such as the defence and security apparatus, public administration, and the economic spheres (Jones, 2020). However, such dominance began to face opposition from the Amhara and Oromo parties which also formed part of the EPRDF coalition. According to Ostebo and Tronvoll (2020), intense rivalry from within the coalition as well as mounting public protests led to the collapse of the EPRDF in 2018. This led to the rise of Prime Minister Abiy. He quickly began to consolidate power with the aggrieved members of the EPRDF to the exclusion of the TPLF who refused to join the new political party (Gavin, 2021).

In addition, members of the TPLF began raising concerns over what they considered as deliberate efforts to reduce their influence and level of autonomy in their region. With Abiy reluctant to enter into a power-sharing agreement with the TPLF, and growing grievances among the TPLF members, conflict between the government and the TPLF became inevitable.

Third, the political and constitutional crisis that emerged due to the delayed elections cannot be ignored in trying to understand the causes of the Ethiopian civil war. Jima and Meissner (2021) observe that the government’s decision to postpone elections citing challenges that had been brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic was instrumental in leading to the violent conflict. This paper also adds that the political trends at the time had significantly reduced trust among different actors in Ethiopia at the time. Far worse, was the decision by the TPLF to conduct elections in their region. Also, the declaration by the government that such elections were illegal provided the justification to declare war on the TPLF.

The decision by the government to declare its operation a war against terrorists worsened the situation. This happened because it not only justified the use of excessive’ force in TPLF-held regions but it also excluded international actors.

The reason is that wars on terrorism can be considered as a domestic issue.

The hardline and reaction of the TPLF also did very little to save the situation.

These combined with other factors contributed to the disaster witnessed during the crisis. The factors included the power struggle between the dominant political parties in Ethiopia; the systematic removal of Tigrayans from government positions; historical land grievances and; the position of Eritrea especially to the extent that it harboured desires to take revenge against the historical actions of the TPLF regime.

A Systematic Review Approach

This study adopted a systematic research approach which was divided into three chronological phases. Phases I and II were used to identify useful sources and the arguments and claims advanced in the existing set of literature. Phase III on the other hand was used to expound on the conceptual and theoretical perspectives of the existing studies. It identified the challenges and shortcomings with regard to the current application of the R2P concept/doctrine.

Phase I was instrumental in anchoring this study within the broader context of existing studies. In this phase, the researchers were able to explore the trends in R2P research such as the nature of research questions and the objectives that have influenced previous studies. This study was able to identify issues that have dominated R2P research and those that have been overlooked. Our in-depth analysis of the existing literature also revealed a dichotomy in the debates surrounding R2P with regard to both academic and policy dimensions. Based on the findings of the existing trends in R2P research, this study was able to anchor its objectives and goals on areas that have been generally ignored. In addition to the conceptual and theoretical aspects of R2P, Phase I of the study also provided an in-depth understanding of the conflicts in Ethiopia. It furthermore shed light on how scholars from multidisciplinary and diverse backgrounds have studied the country and its challenges. What we find is a deficiency in using the R2P approach in understanding the dynamics and state of affairs in Ethiopia. Yet, the country offers an interesting example of the potential challenges and strengths of R2P as a doctrine. To fulfil our objectives during Phase I, we were guided with questions such as: (1)What is the historical dimension of the conflict in Ethiopia?; (2) What have scholars examined and concluded as fundamental issues in the conflict?; (3) What has been the conduct of the Ethiopian government in the context of the R2P doctrine during this conflict?, (4) What are some of the implications of overlooking R2P in our general understanding of asymmetric conflicts currently dotting many parts of the world?

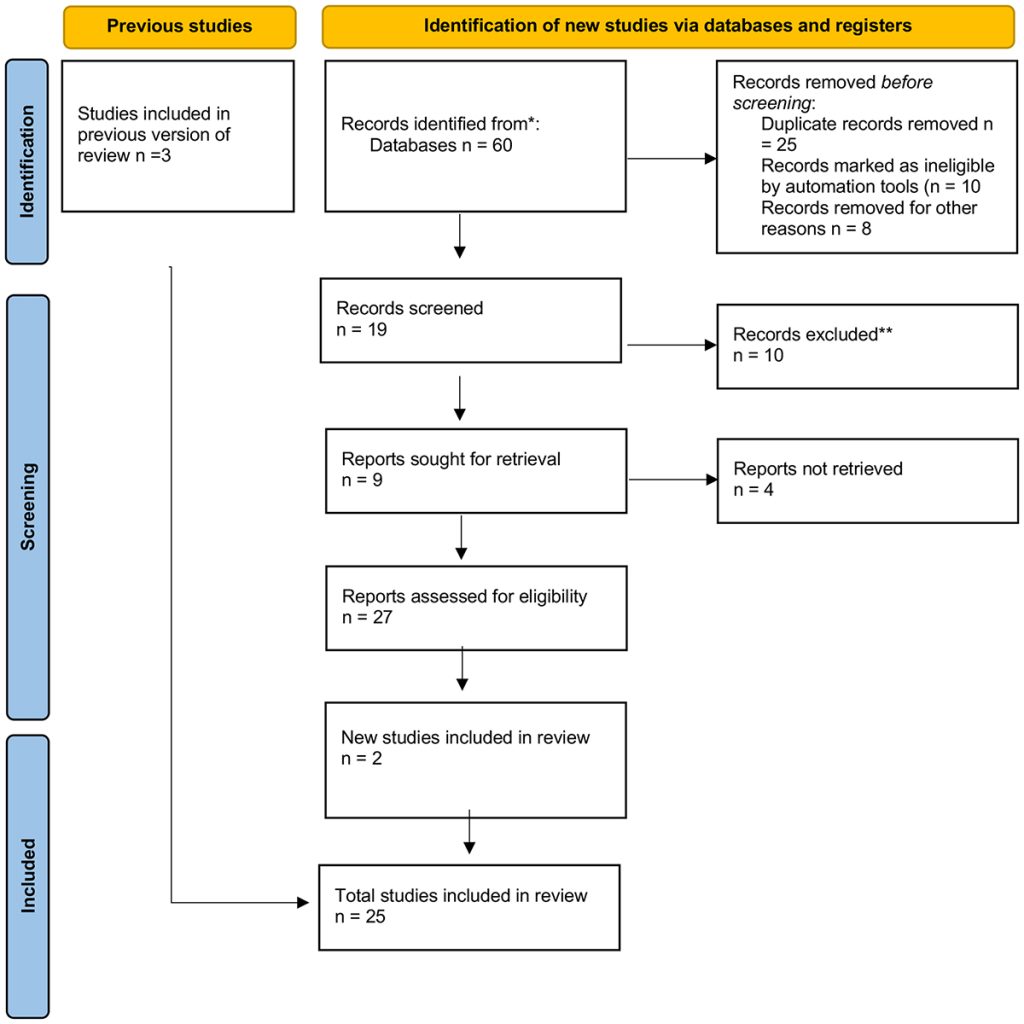

Phase II involved an extensive search of relevant databases and policy platforms where information relevant to this study could be extracted. Searches into these databases were able to generate reports, books, articles, formal publications, and other reputable publications applicable in our study. Scopus, the Web of Science, university libraries, JSTOR, Ebsco, and institutional and government digital libraries were some of the main databases used in this study. Sources were searched using key words such as R2P, Ethiopia-Tigray, asymmetric conflicts/warfare, international law of armed conflict, peace studies, and Africa (see Table 1). The study used the exclusion and inclusion criteria of PRISMA to narrow down on the most valid and relevant literature which were then analysed for the study. A total of 63 sources were generated from the above search. This was before sources that were ineligible, duplicates, and published in languages that the authors did not have a good command of, were eliminated. The eliminated sources did not feature in the analysis of the study. In the end, a total of 25 sources were adopted and used in the study (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Key search words used in the various databases

| Database | Search titles/keywords/terms |

| Web of Science; Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ); Scopus, University Libraries; JSTOR; EBSCO; Academic Databases; Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ); Digital institutional libraries such as those that belong to governments and international agencies. | Peace and conflict resolution; R2P; civil wars; Ethiopian conflict; wartime governance; asymmetric conflicts/warfare; international law of armed conflict; peace studies; Africa; TPLF; non-state violent actors; protracted conflicts; ethnic identity; political settlement; rebel alliances; rebel hierarchies; armed conflict; state building; human security |

Figure 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of PRISMA

In Phase III the authors note that there is a shortcoming in the application of the R2P doctrine to examine conflicts in Africa, more specifically in Ethiopia. This is despite glaring reluctance on the side of government to protect civilians during conflicts. A look at the nature of conflicts in Africa since the turn of the new millennium indicates that most of the conflicts are between state and non-state actors. However, an objective analysis of the violence being experienced in most of the African states gives a different picture. It seems to be overshadowed by narratives of war against terrorism, secessionist movements, or enemies of the state.

Reducing conflicts with regard to these three narratives promotes the need to protect the survival of the state. It underestimates the need to protect civilians which is what R2P seeks to accomplish. Therefore, by using the R2P framework to explore the situation in Ethiopia, the objectives of the paper include: (1) to revisit the debate on the effectiveness/usefulness of international norms or doctrines in dealing with contemporary conflicts; (2) to introduce a new dimension in understanding the situation in Ethiopia. This is a dimension that focuses on the responsibility and obligation of parties involved in conflicts, in this case the responsibility on the part of the Ethiopian government and other parties, including the TPLF and Eritrea; (3) to identify factors that undermine the effectiveness of R2P in Ethiopia and possibly across the world. See Table 2 to understand Karp’s (2015) concept of prospective and retrospective responsibility. But such challenges are not unique to the government of Ethiopia. We observe the same trend with the situation in Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and many other countries.

Table 2. Prospective/Retrospective Responsibility and Prevention/Response: What counts as a failure?

| Prospective Responsibility | Retrospective Responsibility | |

| Prevention | Responsibility for a person, outcome, event or object, irrespective of direct causal involvement. One has failed to fulfil one’s responsibility if one fails to take appropriate preventive action, regardless of whether the outcome or event actually comes to pass. | The responsibility to take all reasonable steps to avoid future harm. One has failed to fulfil one’s responsibility if harm occurs that can be traced back one’s actions or inactions that failed to prevent it. |

| Response | Responsibility to take future action if a pre-specified set of circumstances arises. One has failed to fulfil one’s responsibility if those prespecified circumstances arise, and if one does not respond at all, if one does not respond appropriately, and/or if one is not able to respond. | Responsibility to act in a way that minimises harm or minimises a problem, once harm or a problem is imminent or under way. One has failed to fulfil one’s responsibility if one’s actions are harmful, or if one callously ignores a problem that one has the capacity to address. |

The Concept of the R2P Doctrine (prevention, reaction and reconstruction)

Theexisting literature has been dominated by studies on R2P. Some of these studies have resulted in a debate about whether R2P is an international norm, doctrine, or principle (Cunliffe, 2011; Pattison, 2010; Ercan, 2014). Other scholars (Hehir, 2010) have even questioned whether R2P is a useful framework or “a mere slogan employed for differing purposes shorn of any real meaning or utility”. Murray (2013) has even proposed an interesting argument that the state’s involvement in the prevention of mass atrocities is guided by “rational calculations premised on self-interest”. This can explain why R2P-inspired interventions have been applied in some conflicts and not in others on the grounds of protecting civilians as was the case in the intervention in Libya in 2011. Still, a similar intervention is yet to be seen in Ethiopia where the civilians are finding themselves in threatening situations as a result of the conflict. However, other scholars have cast doubt on whether R2P was even the basis of intervention in Libya (Morris, 2013). This is while proponents of rational choice in states’ intervention such as Nuruzzaman (2014) have a different opinion. Nuruzzaman (2014) uses the lack of intervention in the Syrian conflict, despite the atrocities committed there, as a sign that countries are motivated by their own interests and capacity to intervene.

Can we say that these arguments are justified? Is the R2P an incon-sequential framework? If so can it be strengthened or does it need to be abolished altogether? There are emerging debates that R2P should not only be evaluated in instances where it has succeeded but also whenever states have failed to adhere to the doctrine. Then its usefulness becomes visible since it sets measurable and observable standards. This is in line with the definition of norms by Finnemore and Sikkink (1998) who have argued that a norm is “a standard of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity”. Norms such as the R2P tend to have a socialising effect on states, because they seek conformity, legitimation, and esteem within the international system. This means therefore that despite the challenges facing the implementation of R2P, it should not just be disbanded but improved for better efficiency.

However, despite the pressure to conform to international standards and norms, countries such as Ethiopia, Syria, and even Yemen seem to overlook this pressure. They have committed mass atrocities against civilians. To that end, they violate the R2P norm that requires governments to protect civilians. The question that remains is: Does international reputation matter? And what are some of the reasons for these countries boldly committing atrocities despite the existence of international norms? This study argues that a combination of domestic, regional and international factors contribute to undermining the implementation of the R2P.

One of the justifications is the so-called war on terrorism, which has become a fashionable response by governments that are intent on committing atrocities. As we see in the case of Ethiopia, but also in other cases such as Syria, the government will quickly label a group terming them as a terrorist organisation. By doing so, they legitimise the use of excessive force against them. Such classification could be true based on the fact that civilians and the TPLF also committed acts of violence that can be equated to acts of terrorism. However, it is the limitations that wars on terrorism have on doctrines such as R2P and just war that is of importance to this study. The war on terror is a global phenomenon that has caused both friends and foes to collaborate. The threat of terrorism has also been presented as a serious threat, sometimes even more so than mass atrocities. This can explain how governments are justifying the use of excessive force. The global war on terrorism is also overshadowing the implementation of R2P and this is not a new challenge. In 2001, when the ICISS report was almost being disseminated, the attacks on

11 September in the United States of America (USA) overshadowed

the significance of the report. This was because the global attention shifted to international terrorism and counter-terrorism operations.

Even though the government can be unwilling to or incapable of protecting civilians, R2P offers a way to overcome this shortcoming. This is through international interventions which, by looking at the conflict in Ethiopia, seem not to have been implemented. The question is why did the international community become unable or unwilling to intervene in Ethiopia? As we revisit the R2P doctrine, we need to also understand emerging constraints that hinder international actors from intervening. One is the growing nationalist sentiments and the crisis in multilateralism. Scholars such as Algan et al. (2017), Roth (2017), and Stoker (2019) have examined the growing populist and nationalist sentiments across the world. They have focused on how these could impact states’ involvement in global affairs. This can explain the rise in an inward looking approach by countries that would otherwise have intervened to help resolve some of the instances of mass atrocities across the world.

Another reason why countries are not responding to calls for intervention has to do with the ‘cost’ both in terms of resources and reputation. There seems to be little motivation to intervene in some of the contemporary conflicts. This is visible in the failed attempt by the United States (US) to capture warlords in Somalia, the criticism that emerged after the Libyan intervention, and the disastrous outcome of the Saudi-led coalition. With the fear of backlash and being trapped in unending wars, states seem to shy away from getting involved in other disputes. This is especially so when they have little interest in those countries. This can be one of the reasons why the Ethiopian conflict has not seen regional and international intervention.

Furthermore, intense rivalry among global powers that sometimes plays out at the UNSC cannot be overlooked as a key factor undermining R2P. For international actors to intervene in a conflict, a resolution from the UNSC will go a long way in legitimising such a move. However, the UN as an organisation and liberal institutionalism as an approach to global peace and security, are facing serious challenges and limited success. Such challenges are spilling over and affecting the implementation of other international norms and laws (Meunier and Vachudova, 2018; Hout and Onderco, 2022).

Implications: R2P and the Ethiopian Conflict

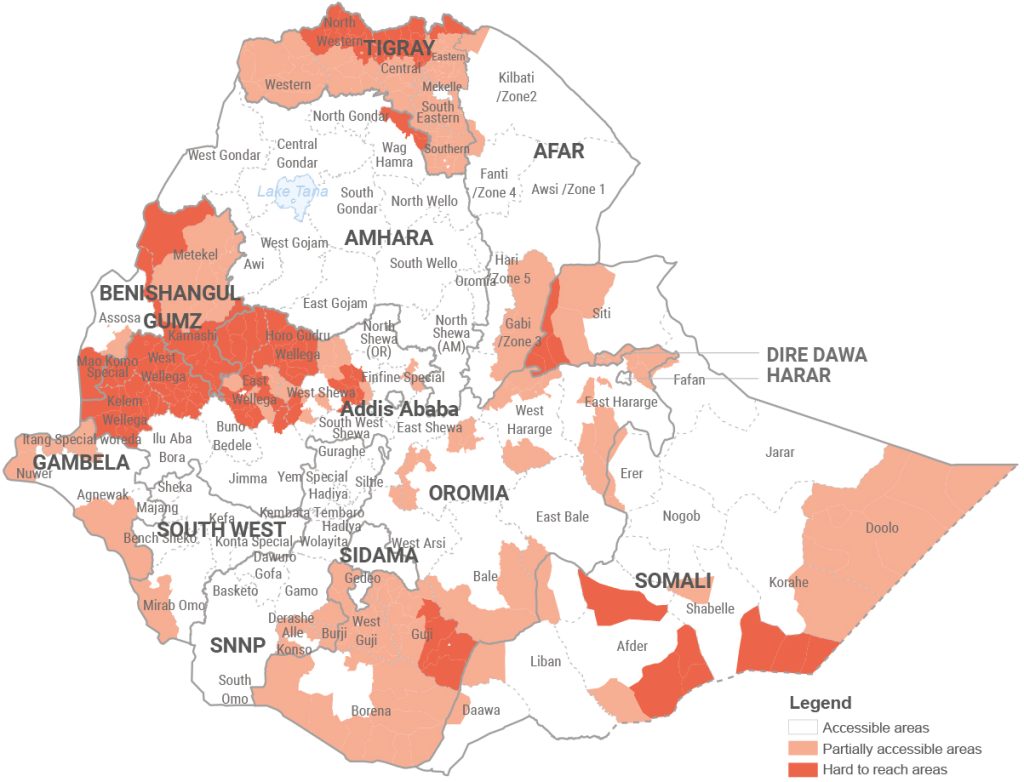

Some steps have been taken by the Ethiopian government to try and end the conflict. The prime minister lifted the state of emergency. He has also collaborated with Tigrayan forces to declare a cessation of hostilities as well as the release of political detainees. More recently, a peace agreement was led by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)/ African Union (AU). It was midwifed by the former president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, and the former Nigerian president, Olusegun Obasanjo. This has changed the dynamics of the conflict. These positive steps may contribute to reduced hostilities and will probably bring an end to the conflict. However, some atrocities had been committed during the war. Who will bear the responsibility? And how will they be held accountable? For example, the Tigray region has continued to experience a blockade in receiving humanitarian support (Berhe et al., 2022). This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Map showing areas which humanitarian aid can access, partly access and hard to reach

Accessible: The population has optimal access to humanitarian assistance and services.

The operational environment to relief operations – from a security perspective – is enabling, partners should apply caution as per normal. There are no phy sical access constraints impacting relief activities.

Partially accessible: The population is able to access limited humanitarian assistance and services. Insecurity continues affecting the safety and security of the population and aid workers, impending relief operations on an intermittent basis. There are some restrictions to the operating environment, including in terms of the rights of the population to access aid. While some partners may be operating in the area, caution should be applied in light of risks and mitigation measures put in place. Some physical access constraints may impact relief activities.

Hard-to-reach: The population’s access to humanitarian assistance and services is highly restricted. The security situation is extremely volatile, compromising the safety and security of the population and aid workers, impending relief operations on a permanent basis. Aid personnel need to be extremely cautious when planning and conducting operations, which should be restricted to life-saving activities, and need to put in place extraordinary mitigation measures and consider alternative operational approaches. Physical environment constraints are having a major impact on relief operations and people’s access to aid.

As stated before, the Tigray region in the north is highly affected by a government blockade of humanitarian support during the conflict. However, we also see that this is not the only region facing these type of problems; other parts of the country such as Sidama, Somali, and Benishangul Gumz are also facing a serious lack of access to humanitarian support (Gesesew et al., 2021; Mulugeta and Gebregziabher, 2022). People living in the said regions face a combination of problems. These include the negative impact of the conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, and economic woes. This has been further exacerbated by the lack of access to humanitarian support, thereby threatening their human security and ability to survive during these tough times (Nyadera and Bingol, 2021; Agwanda et al., 2021). It can be argued that the various efforts to pressure the belligerents in the conflict to end the war could be in line with the R2P spirit. However, such efforts did not yield a lot. For example, the United States sent its Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa, Jeffrey Feltman in 2021 to hold peace talks with the parties involved in the conflict. He did not manage to resolve the war (Oxford Analytica, 2021). Perhaps the view that the United States was not a neutral player in the conflict could have undermined its leverage on the conflict.

Similarly, efforts by the AU to send a delegation to Addis Ababa to broker peace did not materialise. The response from the government that they were dealing with a terrorism challenge meant that the conflict could only be addressed through internal means. Also, since the government declared their actions with regard to the conflict, a counter-terrorism operation, the extent of force to be applied could not be restrained. The UNSC’s response to the conflict also reflects the very challenge of implementing R2P. For example, a statement that the council issued during November 2021, when the war was intense, creates a perception that the international body was helpless to intervene. Instead, members of the council “expressed serious concern”. They “called for refraining from inflammatory hate speech and incitement to violence and divisiveness”. They also “called for the respect of international humanitarian law” without offering any tangible measures of how these issues would be implemented (Tefera, 2022).

Another challenge that could have hindered the implementation of

R2P in Ethiopia can be found in legal controversies that characterise the R2P and existing international norms. For example, the UN Charter discourages and even limits the use of force by its members in other states. Specifically, Article 2, paragraph 4 of the UN Charter states that member states “shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations”. This leaves many countries in a state of dilemma on whether to intervene in other countries’ internal affairs or not. This is further strengthened by Article 2(1) of the UN Charter which emphasises that the organisation “is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its members”. This explains why the Ethiopian government was opposed to international efforts, citing the issue as an internal problem.

Ethical considerations also impact the implementation of R2P. This is especially the case when states consider stopping violations of human rights, even if it means adopting coercive measures. However, the use of coercive measures to stop violations of human rights does not guarantee that civilians will not be victims of such interventions. Furthermore, nationalists tend to dispute the assumption that governments have an ethical obligation to protect the human rights of people in other countries (Yazici, 2019; Williams et al., 2020).

Conclusion

This paper aims to examine the challenges facing the implementation of R2P. It examines the Ethiopian civil war and argues that it offers a unique example of the constraints involved with the protection of civilians and curbing mass atrocities during conflicts. The findings show that the situation in Ethiopia is a result of several factors including: (1) the failure in past interventions such as the situation in Libya, which resulted in more destruction than was intended; (2) the global war on terrorism and how it gives states an ‘excuse’ to use excessive force against a segment of its population; (3) the rise in populism and nationalist sentiments has not only resulted in a crisis in multilateralism, but it has also created a more inward focus by some states, instead of them focusing on international roles; (4) there are also legal challenges that make it difficult to implement R2P. These include constraints that are a result of other international laws and norms that restrain countries from interfering with other countries’ internal affairs; (5) ethical considerations are becoming increasingly important. This is the case given the critique from a nationalist theorist that states do not have to intervene in other countries and protect the human rights of those countries’ citizens.

However, despite the challenges facing R2P, it remains an important international norm that can be used to set standards of how states and international actors are supposed to act during conflicts. The R2P gives an idea of what has been violated and by whom. Such information can be used to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. Indeed, R2P has great potential. It can be used as a yardstick to measure the commission or omission of mass atrocities. However, it can also be improved to become an effective tool for protecting civilians, especially in the wake of the ‘return of wars’.

References

Abbink, J. (2022) The looming spectre: A history of the ‘state of emergency’ in Ethiopia, 1970s–2021. In Routledge Handbook of the Horn of Africa (pp. 302–316). Routledge.

Abdullahi, A. M. (1998) Article 39 of the Ethiopian Constitution on Secession and Self- determination. A Panacea to the Nationality Question in Africa? Verfassung in Recht Und Übersee, 31 (4), 440–455. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.5771/0506-7286-1998-4-440>.

Agwanda, B., Asal, U. Y., Nabi, A. S. G., and Nyadera, I. N. (2021) The Role of IGAD in Peacebuilding and Conflict Resolution: The case of South Sudan. In Routledge Handbook of Conflict Response and Leadership in Africa (pp. 118–128). Routledge.

Algan, Y., Guriev, S., Papaioannou, E., and Passari, E. (2017) The European trust crisis and the rise of populism. Brookings papers on economic activity, 2017 (2), 309–400.

Bayu, T. B. (2022) Is Federalism the Source of Ethnic Identity-Based Conflict in Ethiopia? Insight on Africa, 14 (1), 104–125. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1177/09750878211057125>.

Bellamy, A. J. (2022) Sovereignty Redefined: The Promise and Practice of R2P. The Responsibility to Protect Twenty Years On: Rhetoric and Implementation, 13–32.

Berg, A. (2022) The Crisis in Syria and the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). The Interdisciplinary Journal of International Studies, 12 (1), 7–7.

Berhe, E., Ross, W., Teka, H., Abraha, H. E., and Wall, L. (2022) Dialysis service in the embattled Tigray Region of Ethiopia: a call to action. International Journal of Nephrology, 2022, 1–6.

Cohen, R., and Deng, F.M. (2016) Sovereignty as Responsibility: Building Block for R2P. In Bellamy, A.J and Dunne, T. eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Responsibility to Protect. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 74–93.

Cunliffe, P. (2011) Critical Perspectives on the Responsibility to Protect: Interrogating Theory and Practice. Routledge: London.

Dias, A. M and Yetena, Y. D. (2022) Anatomies of Protest and the Trajectories of the Actors at Play. In Sanches, E.R. Popular Protest, Political Opportunities, and Change in Africa (1st ed., pp. 181–199). Routledge. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003177371-11>.

Ercan G, (2014). R2P: From Slogan to an International Ethical Norm. Uluslararası İlişkiler / International Relations, 11 (43), pp. 35–52.

Fessha, Y. T. (2022) What language in education? Implications for internal minorities and social cohesion in federal Ethiopia. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19 (1), 16–34. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1696348>.

Finnemore, M and Sikkink, K. (1998) International norm dynamics and political change. International Organisation 52 (4): 887–917. Freedom House. (2022) Ethiopia Country Report. Available from: <https://freedomhouse.org/country/ethiopia/freedom-world/2022>.

Gesesew, H., Berhane, K., Siraj, E. S., Siraj, D., Gebregziabher, M., Gebre, Y. G and Tesfay, F. H. (2021). The impact of war on the health system of the Tigray region in Ethiopia: an assessment. BMJ Global Health, 6 (11), e007328.

Ghosh, B. (2022) The World’s Deadliest War Isn’t in Ukraine, But in Ethiopia. Bloomberg. Available from: <https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-

worlds-deadliest-war-isnt-in-ukraine-but-in-ethiopia/2022/03/22/eaf4b83c-a9b6-11ec-8a8e-9c6e9fc7a0de_story.html>.

Hout, W and Onderco, M. (2022) Developing Countries and the Crisis of the Liberal International Order. Politics and Governance, 10 (2), 1–5.

Junk, J. (2016) Testing boundaries: Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar and the scope of R2P. Global Society, 30 (1), 78–93.

Karp, D. J. (2015) The responsibility to protect human rights and the RtoP: prospective and retrospective responsibility. Global Responsibility to Protect, 7 (2). pp. 142–166.

Katema, M and Diriba, G. (2021) State of Ethiopian Economy: Economic Development, Population Dynamics, and Welfare. Ethiopian Economics Association. Available from: <https://eea-et.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SEE-Book-2020_2021.pdf>.

Kul, S. (2022) Libya and Syria: The Protection of Refugees and R2P. The Responsibility to Protect Twenty Years On: Rhetoric and Implementation, 133–151.

Lepard, B. D. (2021) Challenges in implementing the responsibility to protect: the security council veto and the need for a common ethical approach. The Journal of Ethics, 25 (2), 223–246.

Martin, S. (2011) Sovereignty and the responsibility to protect: mutually exclusive or codependent? Griffith Law Review, 20 (1), 153–187.

Meunier, S and Vachudova, M. A. (2018) Liberal intergovernmentalism, illiberalism and the potential superpower of the European Union. JCMS: Journal of common market studies, 56 (7), 1631–1647.

Morris, J. (2013) Libya and Syria: R2P and the spectre of the swinging pendulum. International Affairs 89(5): 1265–1283.

Mulugeta, A and Gebregziabher, M. (2022) Saving children from man-made acute malnutrition in Tigray, Ethiopia: a call to action. The Lancet Global Health, 10 (4), e469–e470.

Murray, R.W. (2013) Humanitarianism, responsibility or rationality? Evaluating intervention as state strategy. In: Hehir, A and Murray, R.W .eds. Libya: The Responsibility to Protect and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention. New York: Palgrave, pp.15–33.

Murray, R. W. (2012) The challenges facing R2P implementation. In The Routledge Handbook of the Responsibility to Protect (pp. 78–90). Routledge.

Newman, E. (2013) R2P: Implications for world order. Global Responsibility to Protect, 5(3), 235–259.

Nuruzzaman, M. (2014) Revisiting ‘Responsibility to Protect’ after Libya and Syria.

E-International Relations, 8 March. Available from: <http://www.e-ir.info/2014/03/08/revisiting-responsibilityto protect-after-libya-and-syria/>.

Nuruzzaman, M. (2022) “Responsibility to Protect” and the BRICS: A Decade after the Intervention in Libya. Global Studies Quarterly, 2 (4), ksac051.

Nyadera, I. N. (2018) South Sudan conflict from 2013 to 2018: Rethinking the causes, situation and solutions. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 18 (2),

59–86.

Nyadera, I. N and Bingol, Y. (2021) Human Security: The 2020 Peace Agreement and the Path to Sustainable Peace in South Sudan. African Conflict & Peacebuilding Review, 11 (2), 17–38.

Nyadera, I. N, Islam, M. N and Shihundu, F. (2023) Rebel Fragmentation and Protracted Conflicts: Lessons from SPLM/A in South Sudan. Journal of Asian and African Studies.

Oxford Analytica. (2021) Ethiopia’s Tigray tensions will deepen. Emerald Expert Briefings, (oxan-es).

Pattison, J. (2010) Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility To Protect: Who Should Intervene? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pedersen, M. B. (2021) The Rohingya Crisis, Myanmar, and R2P ‘Black Holes’. Global Responsibility to Protect, 13 (2–3), 349–378.

Pison Hindawi, C. (2022) Decolonizing the Responsibility to Protect: On pervasive Eurocentrism, Southern agency and struggles over universals. Security Dialogue, 53 (1), 38–56.

Roth, K. (2017) The dangerous rise of populism: Global attacks on human rights values. Journal of International Affairs, 79–84.

Salemot, M. A. (2021) Non-derogable Rights during State of Emergency: Evaluation of the Ethiopian Legal Framework in Light of International Standards. Hawassa UJL, 5, 175.

Stoker, G. (2019) Can the governance paradigm survive the rise of populism?. Policy & Politics, 47 (1), 3–18.

Tefera, F. F. (2022) The United Nations Security Council Resolution 2417 on Starvation and Armed Conflicts and Its Limits: Tigray/Ethiopia as an Example. Global Responsibility to Protect, 14 (1), 20–27.

Thakur, R and Weiss, T. (2009) R2P: from idea to norm—and action?. Global Responsibility to Protect, 1 (1), 22–53.

Wamulume, W. G., Tajari, A., & Sariburaja, K. (2022). (In) Effectiveness If Military Intervention under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P): A Case Study of Libya.

Open Access Library Journal, 9 (5), 1–22.

Welsh, J. M. (2021) The Security Council’s Role in Fulfilling the Responsibility to Protect. Ethics & International Affairs, 35(2), 227–243.

Williams, C. R., Kestenbaum, J. G. and Meier, B. M. (2020) Populist nationalism threatens health and human rights in the COVID-19 response. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (12), 1766–1768.

Yazici, E. (2019) Nationalism and human rights. Political Research Quarterly, 72 (1), 147–161.

Ylönen, A. (2018) Is the Horn of Africa’s ‘Cold War’ over? Abiy Ahmed’s early reforms and the rapprochement between Ethiopia and Eritrea. African Security Review, 27 (3–4), 245–252. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2019.1569079>.

Záhořík, J. (2017) Reconsidering Ethiopia’s ethnic politics in the light of the Addis Ababa Master Plan and anti-governmental protests. The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 8 (3), 257–272. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2017.1370330>.

Zähringer, N. (2021) Taking stock of theories around norm contestation: a conceptual re-examining of the evolution of the Responsibility to Protect. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 64.

Zewde B, Pausewang, S and Yamāh̲barāwi ṭenāt madrak (Ethiopia) (Eds.). (2002). Ethiopia: The challenge of democracy from below. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet ; Forum for Social Studies.

Zimmerman, S. (2022) R2P and Counterterrorism: Where Sovereignties Collide. Global Responsibility to Protect, 14 (2), 132–154.