Abstract

South African foreign policy is premised on the African Renaissance concept of good governance. The country’s good governance objectives are to strive for world peace and the settlement of all international disputes by negotiation – not war. Furthermore, South Africa’s foreign policy is informed by its domestic policy which is guided by the vision of a democratic South Africa that promotes best practices with regard to good governance regionally and globally. Given its vision of effective global governance, South African foreign policy faces many challenges due to the various continental demands that include global food shortages, low intensity conflict, and low employment levels. This article argues that South Africa cannot accomplish its foreign policy objectives by itself and advocates the use of civic interest groups as a strategic tool of implementing soft power. In demonstrating the impact of civic interest groups as a foreign policy instrument, the article illustrates how globalisation has changed the world of international diplomacy, requiring non-state actors to become more active in transforming the economic and political playing field. Throughout the discussion, the South African Dialogue for Women is used as a case study that demonstrates how South Africa could further achieve its objectives of African Renaissance by supporting civil society initiatives in promoting good governance on the ground.

1. Introduction

In July 2004, the South African Women in Dialogue (SAWID) initiative, supported by the office of Mrs. Zanele Mbeki at the office of the Presidency, facilitated a dialogue with Burundian women. The South African and Burundi Women in Dialogue (SABWID) was the second intercontinental peace dialogue organised to promote peace among women in the Great Lakes Region, by developing and sharing strategies for mainstreaming women’s issues and by discussing post-conflict developmental challenges (South African and Burundi Women in Dialogue 2004:6). The objectives of dialogues such as SABWID are usually designed to bring together stakeholders to discuss priorities and needs in the social and human sciences, and to agree on a particular plan of action. Interest groups, civic education organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), parastatals, and others have become successful in their action plans to address conflict and provide capacity building and mediation, thereby facilitating democratic measures. Their impact on democratisation has expanded their influence on global affairs making them attractive agencies of foreign policy.

Due to the influence of interest groups on the global arena, there is much debate about the role of diplomacy in shaping foreign policy. The modern diplomat is very far removed from the original job description of an ambassador in the era of Greek city states, when diplomacy was limited to the interaction between monarchs to maintain peace. We operate in a much more complex environment, where the Department of Foreign Affairs is no longer the only player in the world of international diplomacy. Other departments of state as well as non-state actors now work in areas that were previously the sole preserve of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This level of influence by interest groups has positioned them to become effective foreign policy tools for promoting soft power in various countries such as India, Canada, and the United States. The basic concept of power is the ability to influence others to get them to do what you want. ‘Soft power’ is the ability to achieve desired outcomes in international affairs through attraction rather than coercion. It works by convincing others to follow, or getting them to agree to, norms and institutions that produce the desired behaviour (Nye & Owens 1990).

Due to its regional work the SABWID dialogue, the focus of this study, is considered a civic education project that qualifies as an option of soft power application by the South African government. SABWID, which is considered as a civic education organisation, began engaging in regional capacity building activities in order to resolve conflict in countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burundi. Civic education organisations are a brand of institutions that have started broadening the scope of civil society programmes that have a democratic focus (Carothers & Ottaway 2002). Civic education usually involves efforts to teach people the basic principles and procedures of democracy (Carothers & Ottaway 2002). The involvement of gender-based civic education groups such as SABWID is a positive breakthrough, as women’s interest groups are increasingly influencing the ability of governments to set their own policies, and to promote and protect human rights in general.

By assessing SABWID, this article will determine whether South African interest groups can be utilised as a foreign policy tool that could promote African Renaissance through transformation cooperation. SABWID was selected as a case study because of the following:

- It focused on a wide range of local Burundian civil societies and political groups promoting citizenry participation and reconciliation.

- The dialogue occurred prior to the electoral process in Burundi. The electoral process was viewed as an important initial step towards the creation of a legitimate independent government making it a key component of the democratisation process.

- The dialogue was gender-based, which is critical, given the role of women during the post-conflict reconstruction period.

- The dialogue’s objectives were in line with promoting human security and the African Renaissance.

According to Ms Sue van der Merwe, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, the mandate of the Department of Foreign Affairs is to ensure that South Africa conducts its foreign policy in a manner that promotes citizenry participation and the human security of its people, through a principled foreign policy which should also be sought for the peoples of the continent of Africa.1 SABWID’s objectives of promoting good governance measures, outlined by Sue Van der Merwe, were in line with South Africa’s application of African Renaissance principles such as integration and transformation of security, and healing and reconciliation within the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) framework (South African and Burundi Women in Dialogue 2004).

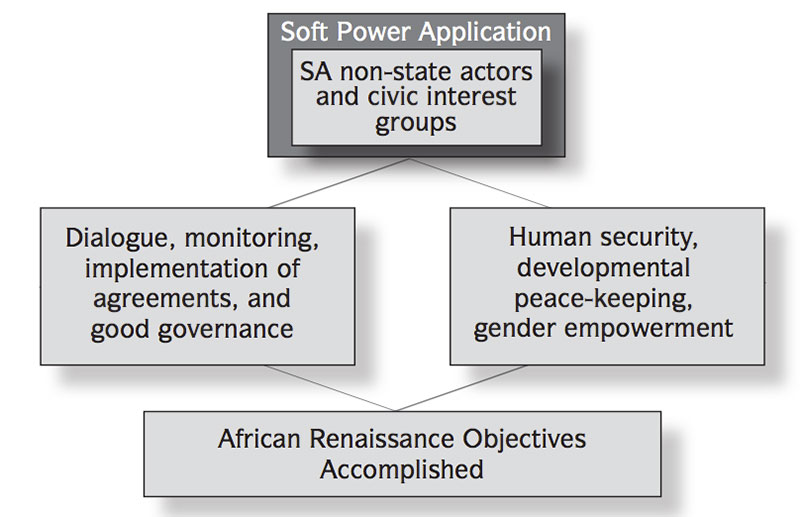

Diagram 1

The African Renaissance concept favours a developmental, peaceful and multilateral approach to resolve conflicts and instability on the continent and establish good governance (Institute for Security Studies 2004).

Foreign Affairs Minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma elaborates further on South Africa’s foreign policy goals being focused on African Renaissance principles when she asserts that ‘the promotion of peace and security is one of South Africa’s most important objectives in the region. South Africa’s foreign policy agenda includes the strengthening of conflict prevention and resolution capabilities of the region and rendering assistance in monitoring and addressing domestic issues that affect regional stability’.2 The fact is the African continent still consists of an abundant number of weak states, failed states, states undergoing post-conflict reconstruction, and states still attempting to implement consolidated democracy. These countries form a large cluster that South African foreign policy may have to address at one point or another. By implementing civic education organisations or interest groups as a foreign policy tool, South Africa will not be an exception in the international community as countries such as Canada have adopted a strategy of using interest groups to promote their foreign policy measures in a positive way. Canadian civil societies, research institutes, NGOs and media houses such as the Canadian International Information Strategy (CIIS) have become an optional medium for enhancing Canadian influences – its soft power – and promoting the delivery of Canadian foreign policy (Axworthy 1997:187).

The impact of interest groups or civil societies on the African continent in performing capacity building measures – such as developmental peacebuilding, conflict resolution and public service delivery – also explains how they have become a growth industry on the continent. Human security is an essential link for political development as it encompasses human rights, good governance, access to education and health care and ensuring that each individual has opportunities and choices to fulfil his or her potential (Annan 2000). Technically, human security is one of the key functions that are to be provided by the state. Instead, weak states such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Liberia and Sierra Leone continue to rely on interest groups to provide their citizens with basic and yet critical elements of human security, and community empowerment measures. South Africa has established a strong record of contributing significantly in facilitating human security in weak states such as the DRC by placing considerable effort and resources, both financial and human, into economic and political development. For example, South Africa had six government departments working in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including their defence force and electoral commission.

This developmental approach is attributed to a ‘soft power’ approach in promoting change in weak states. Joseph Nye who coined the soft power theory indicates that there are three kinds: the military approach where you can threaten or coerce the politicians into certain action; the second one is economic where you seduce them with payments; and the third kind is to attract people, or co-opt them, to do what you want. Soft power is a product of globalisation which is described as a process by which the people of the world are unified into a single society. This process is a combination of economic, technological, socio-cultural and political forces which have changed the way foreign policy is implemented (Croucher 2004:10). The relevance of these forces is demonstrated through the influence exercised by the media and civic education groups, which started becoming more prominent in the twentieth century. Equally important are the specialist advocacy groups that engage in public diplomacy around issues of peace and security.

2. The impact of the SABWID Dialogue on promoting African Renaissance principles

Civil war broke out in Burundi, a nation of approximately 6 million people, in October 1993 after Tutsi paratroopers assassinated the country’s first democratically elected leader, a Hutu (Security Brief 2003:51). The civil war was the result of long standing ethnic divisions between the Hutu and the Tutsi tribes in Burundi. Under international pressure, the warring factions negotiated a peace agreement in Arusha in 2000, which called for an ethnically balanced military and government, and democratic elections (British Broadcasting Corporation News 2004). The Burundi Civil War lasted from 1993 to 2005 with an estimated death toll standing at 300 000 (Mail & Guardian Online 2008).

South Africa assumed a leading role in addressing the Burundi conflict which is demonstrated by the diplomatic negotiations and peacekeeping process led by top leaders such as former President Nelson Mandela and former Deputy President Jacob Zuma. When South Africa became involved with Burundi, the United Nations that is tasked with the Responsibility to Protect did not even want to become involved at the initial phases after the Arusha Accords were signed. Case in point, the United Nations, designated by the Accords to provide troops to protect opposition leaders, refused to do so until there was an effective cease-fire in Burundi. South Africa, through its African Renaissance commitment, provided the lead by providing the necessary soldiers in Burundi to facilitate the peace process.

Former President Nelson Mandela, who was the Facilitator for the Burundi Peace Negotiations, spearheaded the involvement of gender in the peace process, which was considered essential for democratisation. This gender initiative was a positive step in promoting reconciliation as previously Burundian male delegates who participated in Arusha merely permitted temporary observer status to three Hutu and three Tutsi women, despite the urging from the former facilitator, Mwalimu Nyerere, to fully involve women.3 The delegates insisted that women should participate as part of political parties or civil society, which had already been given participatory status, and emphasised the need for a larger number of women delegates who would represent the broad spectrum of constituencies.4 South African foreign policy initiatives, through the involvement of the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), were successful in ensuring that all 19 political parties involved in the Burundi peace negotiations would guarantee that women participate in the peace process and that their concerns regarding the implementation of the peace accord would be taken into account.

These measures by South Africa in promoting gender were critical as an estimated 65% to 70% of Burundi refugees during that period were women and children. Moreover, the impact of the conflict on Burundi women became particularly severe, characterised by rape, killing and forced displacement (United Nations Development Fund for Women 2000b). Given the aforementioned conflict dynamics, and the path that was charted in promoting gender, the SABWID dialogue in addressing the Burundian peace process was significant. In an attempt to establish the significance of the dialogue, respondents were assessed on issues related to gender mainstreaming, reconciliation, South Africa’s impact on Burundi, the SABWID dialogue impact, and the prospects of having a regional AU dialogue structure for peace. Some of the surveys also attempted to establish whether UN Security Council Declaration 1325, which was passed unanimously on 31 October 2000 (Resolution S/RES/1325), did address the impact of war on women, and whether women’s contributions to conflict resolution and sustainable peace were applicable during the dialogue.

Human Rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, that monitor governmental actions, were one of the first prominent politically based interest groups that became a major force of globalisation. Along with the thousands of politically based organisations and advocacies that began to mushroom as a donor-based industrial complex, globalisation then produced millions of competing capacity-building civil societies that took over the role of much needed public service delivery in under-developed countries. Due to the proliferation of these organisations which are typically funded by the West, weak states are now outnumbered and out-resourced by these groups (Mohammed 2007). Some governments have now come to view the original interest groups as a strategic way of promoting positive goals and objectives. These governments have come to realise that it is through advocacy or capacity building that these various interest groups perform some of the key pro-democratic roles – articulating citizens’ interests and disciplining the state (Mohammed 2007).

The emergence of South African based trans-national civic education groups is a rather recent phenomenon that only began to emerge in the post-apartheid era. South African organisations only then started joining international civil societies in monitoring or assisting developing countries, specifically those that are affected by conflict in the late twentieth century. Consequently, compared to interest groups in regions and countries like Canada and India, South African interest groups have not been actively taken into consideration in the formulation of South African foreign policy. European Union foreign policy, according to Philippe van Amersfoort (2005), has a specific goal aimed at strengthening civil society in developing countries to achieve its objectives, notably in the field of human rights and democratisation. In India, on the other hand, interest groups are actually trained to have an effective impact on the country’s ‘Look East’ foreign policy by involving them in the economic and political growth of Asia (Indo-Asian News Service 2007).

However, despite its slow pace in utilising South African interest groups as a strategic element of its foreign policy, the South African government has been effective in establishing a positive history of involving its civil society in political processes regionally. For example, consultation with South African civil society and the private sector has been underway since 2005 leading to the NEPAD Implementation Strategy for South Africa (NISSA). As stated earlier, during the electoral process in the DRC, South Africa sent representatives from a number of civil societies in various parts of the nation to go and monitor elections in the DRC. South African civil societies have also been involved in monitoring the Zimbabwean elections. South African civil societies have now been actively involved in the process of diplomatic relations between South Africa and China. These aforementioned exercises are an excellent orientation towards civil society’s active participation in an international democratic process.

Along with interest groups that are usually consulted by the South African government to engage in foreign policy-based exercises, there are civic education organisations such as the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) that have independently managed to establish an impressive regional footprint in promoting the African Renaissance. ACCORD has been in the fore-front of promoting a South African Renaissance by promoting conflict transformation, peace and stability in at least 26 African countries for over 15 years. ACCORD is very relevant to South Africa as a foreign policy instrument as the institution has been actively working with various grass roots organisations in the region. The organisation’s primary goal of influencing positive political developments through promoting dialogue and institutional development as an alternative to protracted conflict (Indo-Asian News Service 2007) is not very different from African Renaissance principles. The dialogue approach used by ACCORD and SABWID, albeit at different levels, is premised on using communication to influence state actors and civil society members to act a certain way.

Dialogue is the interaction between people with different viewpoints, intent on learning from one another. The purpose of this learning is to lay the foundation for creating a new understanding and new solutions (Hardy et al 1998). Peace dialogue is defined as a dialogue practice of mutual accommodation applied in different dialogue procedures to achieve social transformation. The SABWID dialogue procedural tools were developed through local South African consultants such as Dr. Cheryl Hendricks and Allison Lazarus who both worked at the Centre for Conflict Resolution during this period. Their main focus was to promote interaction, understanding, and reconciliation amongst the Burundian women who were from different political and civil society groups. Various South African gender-based civil societies were also included in the dialogue as a method of exchanging lessons between the two countries, and advancing peaceful coexistence amongst Burundian people.

In assessing SABWID’s impact on South African foreign policy, a scientific analysis was done by interviewing some of the dialogue participants. The methodology used to determine the dialogue’s effectiveness focused only on the Burundian participants. The assessment was inclusive of surveys that questioned respondents about their views of the dialogue and African Renaissance. Implementation of the surveys was based on purposive samples, which required that the investigator purposefully select individuals or groups for their relevance to the research study (Simon 1986). Consequently, Burundian dialogue participants had to be purposefully selected based on their availability in Burundi.

a. Gender mainstreaming

The UN Security Council recognises the need to mainstream a gender perspective into peacekeeping operations in accord with the Windhoek Declaration and the Namibia Plan of Action on Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peace Support Operations (S/2000/693). According to the UN Economic and Social Council, mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications on women and men of any planned actions (including legislation, policies or programmes) in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres – so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate goal is to achieve gender equality (United Nations Economic and Social Council 1997: E.1997 L.10. Para. 4). More importantly, gender mainstreaming has been endorsed by the Beijing Platform for Action as the approach by which ‘governments and other actors should promote an active and visible policy of mainstreaming a gender perspective in all policies and programmes, so that, before decisions are taken, an analysis is made of the effects on women and men, respectively’ (United Nations Economic and Social Council 1997: E.1997 L.10. Para. 4).5

Given the marginalisation of women in the initial stages of most international peace processes, respondents were questioned about whether SABWID had effectively promoted gender mainstreaming through developmental peacekeeping strategies. 23% of the participants felt that SABWID had done a good job, 45% gave a better rating, while 3% felt they had provided excellent strategies. Most of the women also emphasised that sharing strategies of gender mainstreaming and promoting peace amongst the women was a relevant aspect of peacebuilding, particularly given the divisions that already existed due to ethnic or party lines. Gender equality and women’s empowerment, as emphasised earlier, are an integral part of national development, peacebuilding and conflict resolution. Empowering women on the ground in order that they play an equal part in security and maintaining peace, politically and economically, and be represented adequately at all levels of decision making – at the pre-conflict stage, during hostilities, and at the point of peacekeeping, peacebuilding, reconciliation and reconstruction – not only promotes African Renaissance but achieves the objectives of soft power through diplomatic means.

b. Reconciliation

Reconciliation has increasingly become important in the context of conflict prevention and development cooperation. While the physical reconstruction of infrastructure and the re-building of basic administrative and governmental structures are often the focus of international engagement, less attention is usually given to the re-building of societal links. Therefore, a society such as Burundi which had undergone a brutal war was bound to be fragmented. Participation of conflict resolution experts was an essential strategy of the dialogue because the causes of conflicts often continue to exist during democratic transition and after elections, making reconciliation initiatives an essential component of conflict resolution.

As established earlier in this discussion, dialogue involves interaction between people with different viewpoints, intent on learning from one another to sometimes achieve understanding and reconciliation. The SABWID dialogue ensured the participation of various involved political parties and civil societies, which made the study relevant in determining whether an understanding and reconciliation would be achieved amongst the Burundi women. Table one indicates some of the various political groups that attended the dialogue.

Table 1: SABWID Political Participants

| NAME | ACRONYM |

| Front Pour la Démocratie au Burundi | Frodebu |

| Union Pour le Progrès National | Uprona |

| Conseil National de Défense de la Démocratie – Force pour la Défense de la Démocratie | CNDD-FDD |

| Parti pour la libération du people Hutu | Palipehutu |

According to most respondents, the promotion of peace along party lines remained a challenge – as most non-CNDD-FDD members viewed the ruling government during that period as endorser of South African foreign policy.

Non-CNDD-FDD members kept pressing for a balanced representation of participation in future dialogues. However, these views, constantly voiced by non-CNDD-FDD members, had little effect on thinking that promoted reconciliation. Consequently, the dialogue promoted ownership of the peace process as the Burundian women, despite their differences in opinion, were seeking to be reconciled.

c. SABWID influence on the Burundian electoral process and democratisation

Resolution 1325 calls on all actors involved to adopt a gender perspective when negotiating and implementing peace agreements, including measures that ensure the protection of and respect for human rights of women and girls, particularly as they relate to the constitution, the electoral system, the police and the judiciary. As a capacity-building strategy of the electoral process, the SABWID dialogue was hosted prior to the elections in 2005. The Republic of Burundi held several elections in 2005, ensuring that the nation returned to constitutional democratic rule after a devastating civil war. During my field research in Burundi, one lady confirmed that before coming to South Africa she had no knowledge of how to galvanise women to become involved in the electoral process. She maintained that SABWID helped her raise an awareness of the electoral process among the women in her community.

Participants in the dialogue had to respond to a four-part survey on the influence of SABWID in promoting its envisaged outcomes. As to whether the dialogue promoted peace amongst women, 26% gave SABWID a fair rating, 26% a good rating while only 2% each gave ratings of ‘better’ and ‘excellent’. Upon interviewing some of the Burundian participants, a number of them indicated that they were able to facilitate the knowledge they had learnt from SABWID amongst their communities.

Several of the respondents felt that the dialogue mobilised women despite ethnic and political differences on common issues. Respondents also indicated that the dialogue illustrated the need for women to work together on political issues related to the well being of the country. Several women indicated that the dialogue was a positive tool with regard to the African Renaissance as well as South African foreign policy’s key objective of democratisation on the continent. Regarding the implementation of the dialogue, there were negative responses which asserted that some lacks of organisation and structure contributed to the respondents not taking SABWID seriously. Concluding responses were positive again whereby the respondents maintained that dialogue is an effective tool for peacebuilding which should be considered for the African Union in resolving instability.

When the participants were questioned as to whether the dialogue was successful in promoting South Africa’s cause of promoting African renaissance through democracy and peace building initiatives, only 39% recognised South Africa’s leadership efforts in Burundi, while nearly half of the group decided to abstain. This question was critical given the various suspicions that arose regarding South Africa’s objectives in the country and the region. If South Africa will participate in foreign policy activities of this nature in the future, it is essential that the civil societies in the identified country understand South Africa’s African Renaissance objectives.

Democratisation is the process whereby a country adopts a democratic regime. The transition may be from an authoritarian regime to a partial democracy, or to a full democracy, or one from a semi-authoritarian political system to a democratic political system (Putnam 1993). According to Chris Hauss (2003), real democratisation has been achieved only in these cases where the management of the transition process has not been left wholly in the hands of the elites but has rather been supervised by elements from the broader civil society. The involvement of civic associations in the electoral process through dialogues such as SABWID prepared a number of Burundians for their future political participation in a democratic regime. The fact is that horizontally organised social networks through effective civic education develop trust among people, and trust is essential for the functioning of democratic institutions (Mousseau 2000).

As to whether the dialogue was applicable to the Burundi transitional process as facilitated by the South African government, SABWID achieved a ‘yes’ score of 61%. This endorses the UN resolution that emphasises the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peacebuilding, and stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security, and the need to increase their role in decision making with regard to conflict prevention and resolution.

Gender equality and women’s empowerment programs are an integral part of national development, peacebuilding and conflict resolution. The surveys from SABWID dialogue demonstrate that gender dialogue can promote peace and stability. The dialogue was critical as it did impact democratic best practices as indicated by the participants. When asked whether the dialogue effectively addressed presented issues related to security and stability that would facilitate good governance strategies, which is a key pillar of South African foreign policy, 81% provided a resounding yes.

Imparting good governance measures was relevant to Burundi, as institutional mechanisms that favour women’s advancement in spheres of public life are still weak or poorly implemented. Burundi is not an exception: poor implementation is a phenomenon that applies to both stable and conflict-prone countries.

Respondents were also asked whether the African Union (AU) as an institution could benefit from another intercontinental dialogue such as this one, and in this regard some of the following statements were made:

- The political participation of women is critical in intercontinental dialogue.

- The expertise of African women in mediation and peace talks from different countries as in the SABWID combination is critical as participants tend to learn from each other.

- The African Union does not consistently promote regional dialogue amongst civil societies, which is essential for democratisation.

- SABWID should be continued in order to promote dialogue amongst the ethnic groups and gender equality in post-conflict reconstruction.

The responses from the participants emphasised the need for dialogue between ethnic groups and women from both South Africa and Burundi. The surveys also demonstrated the viability of utilising civic education groups to advance the consolidation of democracy through various techniques such as dialogue. Empowering women on the ground through dialogue in order that they play an equal part in maintaining security and peace, politically and economically, and be represented adequately at all levels of decision making – at the pre-conflict stage, during hostilities, and at the stage of peacekeeping, peacebuilding, reconciliation and reconstruction – would not only promote the African Renaissance but would also effectively promote soft power diplomatic processes.

3. Conclusion

The responses on the surveys discussed above demonstrate the possible impact of interest groups such as SABWID for positive soft power implementation. These positive channels of soft power through interest groups contribute to democratic consolidation by strengthening governance mechanisms and promoting open and transparent decision-making processes. Monitoring elections, protecting human rights, exposing government corruption, and supporting capacity-building measures are just a few examples of the work taken on by civil society. In general, interest groups embrace the wide-ranging needs and concerns of the community at large, and typically offer an open forum for the debate and discussion of ideas with the aim of strengthening democratic institutions. Sue van der Merwe argues that to be effective in promoting democracy and economic growth, government requires the cooperation of business, workers and all South Africans including civil societies to take advantage of these opportunities, to promote the country’s image, and to provide good service to investors, tourists and others (Department of Foreign Affairs 2006a).

On the other hand, in using interest groups as a positive tool of foreign policy, South Africa should be cognisant of the objectives and outcomes of the various entities. In regard to the private sector for example, the government should emphasise corporate social responsibility practices. On the African continent currently, there are mixed feelings amongst regional business people and politicians concerned with South Africa’s dominant economic role in the region. These feelings range from hopes that the neighbourhood giant will spark off a region-wide recovery to fears that South Africa will steal a competitive march on the nascent industries and political control of other countries (Economist Intelligence Unit 2004).

As Deputy Minister Van der Merwe argues, if the South African government has adopted deliberate efforts to build the confidence of other countries in our vision, South African businesses that operate on the continent must concentrate on forging partnerships for sustainable development rather than focusing on short-term profit gain. Otherwise South African businesses will continue to feed into stereotypes about unscrupulous business practices (Department of Foreign Affairs 2006b). Along with South African interest groups, South African companies should also engage in localised community-building projects, which will help maintain the country’s image in a positive light and negate the perception that the African Renaissance is just a tool for capitalistic interests. Finally, a multilateral approach through bodies such as the AU and the United Nations remain the best form of addressing the war economy (April 2006).

From a political perspective, positive long-term involvement from more interest groups such as SABWID and ACCORD could help eliminate some of the suspicion that constantly clouds South Africa’s foreign policy. For example, in July 2006 there were claims that South Africa engineered a ‘fake coup’ in Burundi to silence opposition and cover-up large-scale government corruption. This allegation spread through Burundi like a bush fire and re-ignited speculations on South Africa’s desire to colonise the region through its selected leaders. An interest group could, through civic education, win the hearts and minds of the community and reduce the high level of suspicion that sometimes promotes only the negative areas of a country’s global relations.

In the final analysis, the 21st century has basically afforded South African interest groups an opportunity to use globalisation techniques and organisational objectives to promote good governance on the continent. Through its current soft power approach, South Africa should continue playing an active role on the international stage in key areas such as peacekeeping, peacebuilding and disarmament (Axworthy 1997:187). However, the success of South Africa’s soft power approach will heavily depend on the country’s reputation within the international community, as well as on the continued flow of information between diplomats and the grass roots. Interest groups have at times developed questionable reputations that have been identified with the agendas of their countries of origin. President Mbeki has in the past questioned to what extent South African civil society made independent choices. This concern has been argued vigorously on a global level.

For example, a Boston Globe survey ‘identified 159 faith-based organisations that received more than $1.7 billion in USAID prime contracts, grants and agreements from fiscal 2001 to fiscal 2005’ (Ngugi 2007) as part of President Bush’s Faith Based Initiative. The implication for these 159 faith-based institutions was that despite the necessary services they provide they were viewed differently by the global community. It is essential that South African interest groups are never identified suspiciously as government agents, but are regarded as transformation entities strictly designed to promote democratic best practices. Interest groups such as SAWID and ACCORD have managed to maintain a positive image on the global arena which is essential in keeping the country’s image at a respectable level.

The challenge is to devise a strategy that would empower, on the ground, some of the interest groups which would be beneficial for the country. Structure is one of the required tools that would help to prevent the confusion that can be caused when a country is represented by a large number of interest groups that usually end up providing overlapping services in the region. Structure is essential particularly because South Africa has not yet developed a method of ensuring that its countrymen when travelling abroad fully embrace the concept of ‘proudly South African’ as a team. Currently, South African civil societies, civic education groups and government departments visit various countries representing their specific interests. It is not surprising to find a South African province or government department in another country promoting themselves first and South Africa second.

The trick in achieving soft power through effective transformation cooperation in the field is through recognising the ability of interest groups to achieve particular goals in a constructive method that positively and indirectly represents South Africa. A tool of assisting effective interest groups is to also ensure that a civil society rating system that does for global civil society what independent credit rating agencies do for the global financial system is implemented. This rating system could provide accurate information about the backers, independence, goals, and track records of different NGOs. It is essential that globalisation and effectiveness of NGOs are not held hostage by lack of reliable ways of distinguishing organisations that truly represent democratic civil society from those that are tools of uncivil, undemocratic governments (Naím 2007).

Even though most South African military forces serving under the United Nations have pulled out of Burundi, South Africa could remain actively involved through various interest groups. The democratisation path that Burundi is trying to implement is still full of challenges, as it still remains the ‘poorest country’ in the world. Violence and poverty continue to plague the people of Burundi, as those who participated in genocide against Hutus in 1972 – which led to the death of 100 000 Hutus and moderate Tutsis – have never been held accountable for their crimes. There is still a critical need for transformation cooperation that could be implemented in Burundi through various government departments and institutions such as SABWID and ACCORD. For example, proposed mechanisms for negotiating transitional justice have stalled. And recently, both Hutu and Tutsi civilians have allegedly been targets of mass killings and acts of genocide organised by the state and armed militia groups. The attacks have allegedly taken place against a background of government complacency, as in July and August 2006 when more than 30 civilians were killed by the National Intelligence Service.

These attacks demonstrate that democracy promotion remains an essential system that should still be effectively monitored in Burundi. It is fair to say that the issue of democracy promotion has become a central issue in the international system. Indeed, all around the world, people are pressing for their rights to be respected, for their governments to be responsive, for their voices to be heard and their votes to count, for just laws and justice for all. Recognition also is growing that democracy is the form of government that can best meet the demands of citizens for dignity, liberty, and equality (Lowenkron 2007). South Africa’s government, though besieged with South Africa’s own internal problems and pressurised by the international community to invest more of its foreign policy resources in Zimbabwe, should strategise a community-based foreign policy agenda that will promote democracy. The participation of women and the integration of gender issues should remain a priority in the implementation of peacebuilding efforts, and should be improved upon so that they can have a greater impact at regional level. More dialogue initiatives are necessary because negotiation and conflict resolution skills are critical for the maintenance of peace. Women have traditionally been identified as consensus builders. Therefore, further improving their skills through more civic education can lead to more linkages across parties and sectors of society, as well as between men and women, which could contribute to reducing the current low intensity warfare that threatens stability in the region.

Sources

- Annan, Kofi 2000. Security General salutes international workshop on human security in Mongolia. 8-10 May 2000. Available at <www.un.org/news/press/docs/2000>

- Alan, Simon 1986. Field Research Procedures and Techniques for the Social Sciences and Education. Johannesburg: University of Witwatersrand.

- April, Yazini 2006. A Foreign Policy Analysis of South Africa’s Diplomatic Leadership in the DRC. Paper presented to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Aug 2006.

- Axworthy, Lloyd 1997. Canada and Human Security: The Need for Leadership. International Journal 152.

- British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News 2004. Africa: Deadly Clash After Burundi Polls. 15 Oct 2004. Available at <www.bbc.co.uk>

- Carothers, Thomas & Marina Ottaway 2002. Defining Civil Society: The Elusive Team. The World Bank 4 (1).

- Croucher, Sheila 2004. Globalization and Belonging: The Politics of Identity in a Changing World. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Department of Foreign Affairs 2006a. Address by Ms Sue van der Merwe, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, to the South African Institute of International Affairs, Western Cape Branch, Cape Town, 14 Jun 2006.

- Department of Foreign Affairs 2006b. Another World is Possible. Address by Ms Sue van der Merwe, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, at the Business Unity South Africa (BUSA) Cocktail Reception, 17 Oct 2006.

- Economist Intelligence Unit 2004. Mr. Mbeki’s African Renaissance. Available at <www.economist.com> 16 Dec 2004.

- Fourth World Conference on Women 1995. Beijing Platform for Action for Equality, Development and Peace. Beijing Declaration, Sep 1995.

- Hardy, Cynthia, Nancy Phillips & Tom Laurence 1998. Distinguishing Trust and Inter-organizational Relations: Forms and Facades of Trust. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hauss, Charles 2003. Reconciliation. Knowledge Base Essay. Available at <www.beyondintractability.org> Sep 2003.

- Indo-Asian News Service 2007. Civil Society to be Involved in Foreign Policy Framing: Minister Pranab Mukherjee. 16 Jun 2007. Available at <www.freshnews.in>

- Institute for Security Studies 2004. Hawks, Doves, or Penguins? A Critical Review of the SADC Military Intervention in the DRC. Occasional Paper 88. Available at <www.iss.co.za>

- Lowenkron, Barry F. 2007. Realism: Why Democracy Promotion Matters. Keynote speech, delivered by Lowenkron as Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor to the National Committee on American Foreign Policy, New York, 13 Feb 2007.

- Mail & Guardian Online 2008. Burundi Rebels Shell Capital: Bujumbura, Burundi. 23 Apr 2008. Available at <www.mg.co.za>

- Mohammed, Abdul 2007. Ethiopian Foreign Policy Part II: Ethiopia’s Soft Power to Ensure Stability in the Horn. Available at <www.harowo.com> 15 Dec 2007.

- Mousseau, Michael 2000. Market Prosperity, Democratic Consolidation, and Democratic Peace. Journal of Conflict Resolution 44 (4), 472-507.

- Naím, Moisés 2007. What Is a Gongo? How Government-Sponsored Groups Masquerade as Civil Society. Foreign Policy: Washington Post Division, May-Jun 2007.

- Ngugi, Mukoma 2007. African Democracies for Sale. Global Policy Forum. Available at <www.globalpolicy.org> 7 Feb 2007.

- Nye, Joseph & William Owens 1990. The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books.

- Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Security Brief 2003. Political Transition in Burundi. African Security Review 12 (2). Available at <www.iss.co.za>

- South African and Burundi Women in Dialogue (SABWID) 2004. Report of a Dialogue in Pretoria, South Africa, 19-23 Jul 2004.

- United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) 2000a. Women at the Peace Table. Available at <www.unifem.org>

- United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) 2000b. Mandela Ushers Women into Burundi Peace Process. Available at <www.unifem.org> 21 Jul 2000.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council 1997. Gender Mainstreaming in the United Nations. Adopted Jul 1997.

- Van Amersfoort, Philippe 2005. European Civil Society. Asia Europe Journal 3 (3).

Notes

- Address by Ms Sue van der Merwe, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, on the occasion of the Budget Vote Debate of the Department of Foreign Affairs, National Assembly, Cape Town, 15 Apr 2005.

- Address by Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Minister of Foreign Affairs, on the occasion of the Budget Vote Debate of the Department of Foreign Affairs, National Assembly, Cape Town, 3 Jun 2004.

- In the second round of negotiations in Arusha in July 1998, women were regarded as a non-accredited delegation.

- Civil society and religious organisations were already granted permanent observer status (United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) 2000a: 9).

- See also Fourth World Conference on Women 1995:para 13.