Abstract

National dialogues are increasingly recognised as vital tools for resolving political conflicts, fostering state- and nation-building, enhancing social cohesion, and facilitating peaceful socio-economic and political transformation. Despite a growing body of literature examining national dialogues and their outcomes, there remains a gap in understanding their theoretical underpinnings and conceptualisations. This article addresses this gap by conducting a discursive analysis offering an alternative theoretical framework for national dialogues, drawing on three theories: social contract, consociationalism, and conflict transformation. Using secondary data from scholarly journals, reports, political agreements, and documented policies and strategies, this article assesses the theories’ applicability in developing a robust conceptual framework for national dialogues. An analysis of each theory demonstrates that, while they approach peacebuilding from different angles, they share unique and common themes such as participatory governance, addressing root causes, and building trust and cooperation, which are essential in designing and implementing successful national dialogues. Leveraging the unique elements of each theory, the observed insights provide a more comprehensive approach to planning and implementing national dialogues, even in diverse socio-economic and political contexts. The findings’ implications are pertinent to scholars in the field of peace studies, governments, political entities, civil society organisations, and international stakeholders engaged in national dialogue processes.

Keywords: National dialogue, consociationalism, social contract theory, conceptual framework, political crisis, peacebuilding.

1. Introduction

National dialogues are gaining currency in the world as a tool for conflict transformation and to address internal conflicts among conflicting groups and between the state and its citizens (Murray and Stigant, 2021; Felek, 2024). The dialogues are referred to as ‘national’ because they are nationally owned processes established to address political crises, social and economic challenges, or issues of national significance to reach amicable consensus-based solutions. Core elements of successful national dialogue designs include clear objectives, sufficient political will, credible facilitation, adequate inclusivity, public participation, transparency, implementation strategies, deadlock-breaking measures, and adequate resource allocation (Guo et al., 2015; Paffenholz, Zachariassen and Helfer, 2017; Murray and Stigant, 2021). However, despite national dialogues’ increased use and identification of their core elements, there is a theoretical deficiency of explaining assumptions behind national dialogues. The extant literature covers conceptual indicators of how to design and facilitate successful national dialogues, with a dearth of autonomous theories and conceptual frameworks. Scholars such as Blunck and Vimalarajah (2017) explore practitioner conceptions of national dialogues, their design processes and implementation while Guo et al. (2015) and Paffenholz, Zachariassen and Helfer (2017) provide detailed analyses of what constitutes successful national dialogues by drawing lessons from various country case studies.

A robust theoretical framework will help to advance explanatory, descriptive, and analytical scholarship, as well as the practice of national dialogues. This article contributes to this national dialogue discourse by proposing a theoretical framework established by three theories — social contract, consociationalism, and conflict transformation — as useful concepts to explain the underlying assumptions of national dialogues and their core elements. These theories were chosen because, when applied, they are transformative, mitigate and prevent conflicts, and promote peacebuilding. Further, these theoretical attributes of the broader hypothesis of national dialogues are tentative but contributory to the understanding and design of the phenomenon.

This article is structured around three discussion themes: understanding national dialogues, a conceptual framework for national dialogues, and a case study of Zimbabwe. The article commences with an exploration of the concept of national dialogues and the key factors instrumental to their success. Subsequently, it constructs a rationale for the development of a conceptual framework for national dialogues. It then presents a case study of Zimbabwe, which serves as a practical test bed for the proposed conceptual framework, leveraging the country’s extensive history of national dialogues.

2. Understanding national dialogues

A dialogue refers to: “a meaningful interaction and exchange between people (often from different social, cultural, political, religious, or professional groups) who come together through various kinds of conversations or activities with a view to increased understanding” (Dialogue Society, 2023:1). A national dialogue, therefore, can be understood as being an act of thinking together at a national level. Blunck and Vimalarajah (2017:21) define national dialogues as “nationally owned processes aimed at generating consensus among a broad range of stakeholders in times of deep political crises, in post-war situations or during far-reaching political transitions”. This definition highlights the significance of national dialogues in their national ownership and intervention in situations or times of instability. Furthermore, Guo et al. (2015:16) define a national dialogue as “a peacebuilding instrument which seeks to build trust and confidence among national actors, foster inclusive participation, and promote consensus on key political, economic, and social measures during periods of political transition”. Thus, Guo et al. (2015) emphasise the role of national dialogues in conflict resolution and peacebuilding. Yohannes and Dessu (2020:3) offer a different definition of national dialogues, stating that they are “formally mandated, inclusive, broad and participatory official negotiation frameworks, which can resolve political crises and lead countries to political transition”. This definition’s stipulation of the formality of national dialogues begs the question: Should dialogues be ‘formally mandated’ to be accepted as national dialogues?

The above definitions provide three characteristics of what constitutes a national dialogue: (i) the situation prevalent in a country; (ii) the purpose and intention of the dialogue to address a national conflict; and (iii) the level of inclusivity of diverse actors seeking to build a consensus. The definitions proffered imply that a national dialogue is a transformative conflict resolution tool that is applied in an inclusive process involving diverse actors seeking a consensus on issues of national importance. While Guo et al.’s (2015) definition includes social and economic issues, Yohannes and Dessu (2020) confine the ambit of a national dialogue to the resolution of political crises. Yohannes and Dessu also clearly indicate that the dialogues must be formally mandated. Arguably, whether mandated formally or not, a dialogue can be considered ‘national’ if it includes political and other role players functioning at a national level. Therefore, what distinguishes a national dialogue from other dialogues is its geographical scope, level of inclusivity in terms of participation and representation, and discussion of a matter of national importance.

The objective of a national dialogue is to reach a common understanding among diverse stakeholders on a broad range of social, economic, and political issues. Yohannes and Dessu (2020:4) note that national dialogues are convened to resolve political crises and lead countries to political transition, as was the case in Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Kenya. In Benin, Togo, and Mali, national dialogues were organised to usher in governments transitioning from authoritarianism to democracy (Guo et al., 2015). In Zimbabwe and South Africa, national dialogues contributed towards constitutional reforms and coalition governments. In Yemen, the national dialogue process led to the country’s transition to a federal state, while in Bolivia, national dialoguing aimed at consolidating democracy and providing an impetus for institutional reforms, including electoral disputes and constitutional and institutional reforms (Guo et al., 2015; Murray and Stigant, 2021).

In Pakistan, a grand national dialogue was necessary to address three problems:

One, low trust between citizens and their representatives (so that they do not end up being seduced by extremists that mock the system). Two, increased distance between people and decisions about their lives (so that they do not end up being seduced by separatists that offer alternative models). Three, a lack of pluralism (so that minorities feel secure in their own country) (Mosharraf, 2020:1).

Based on the foregoing discussion, a national dialogue could be regarded as an appropriate instrument to address political disputes “over past abuses, power sharing, regional autonomy and territorial claims and [could be] a vital tool for addressing the challenges of managing political transition and building sustainable peace” (Yohannes and Dessu, 2020:3).

National dialogues are not only limited to addressing national political crises and transitions but can also include consultations on national social and economic development solution-seeking processes requiring consensus from stakeholders. For example, Rwanda holds yearly national dialogue forums (Umushyikirano Rwanda) to discuss socio-economic development issues of national importance. In November 2023, the country held a national dialogue on human rights while in January 2024, it held a national dialogue on national unity, development, and youth empowerment (Bahati, 2024).

However, it is important to note that the motivation for convening national dialogues is not universal; it is complex and varied. Some political parties and civic institutions insist on facilitating national dialogues, genuinely hoping for an inclusive engagement aimed at transforming existing conflicts. Conversely, some “sitting leaders seek to cement their power, extend their terms or co-opt opposition while placating critics under the guise of consultation and inclusion” (Murray and Stigant, 2021:5). For example, in 2023, Sudan facilitated a “strictly choreographed” national dialogue process to silence critics and co-opt weak opposing parties into the ruling party’s political agendas without genuinely promoting inclusive problem-solving processes (Ottaway, 2023:1). In Zimbabwe, the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) established the Political Actors Dialogue (POLAD) in 2018, co-opting weak opposition parties and mollifying the mainstream opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC)-Alliance party.

Similarly, the Zambian government, led by the Patriotic Front (PF), sought to facilitate a raft of constitutional and legislative reforms that would benefit them, using the National Dialogue Forum (NDF) from 2019 to 2021. The NDF was tightly controlled by the government, and it was criticised for its lack of inclusivity and broad public participation (Lumina, 2019). The outcomes of the forum were highly disputed and contributed to increased polarisation and division within the country (Mukunto, 2021). Like the Zimbabwean POLAD, Zambia’s NDF was designed to protect the interests of the ruling PF party, as argued by Cheeseman (2019).

National dialogues differ from (national) negotiations or mediation by virtue of their objectives and conduct. Mediation involves a third party in addressing a conflict, whereas negotiation involves bringing the conflicting parties together to find common ground. Both processes do not oblige inclusivity (broad-based participation and representation) and they are not broadly consultative. Contrarily, a national dialogue promotes inclusivity and broad representation and participation of various groups to reach a consensus. Moreover, national dialogues expand participation into integrating various groups and interests beyond political and military elites (Papagianni, 2014). Conversely, mediation and negotiation are habitually exclusive, discrete, and involve a few elites away from the entire societal actors (Guo et al., 2015). However, there are overlaps in these three alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. Either mediation or negotiation or both may take place before, after, or parallel to a national dialogue (Blunck and Vimalarajah, 2017). This means that in practice there is a fluid distinction between mediation, negotiation, and national dialogue.

2.1 Essential factors for successful national dialogues

Designing national dialogues is a complex political process that necessitates careful planning and consideration, including ensuring adequate stakeholder representation, building trust among actors, and establishing mechanisms for implementation of agreements (Papagianni, 2014). While drawing lessons from the seminal work by Paffenholz, Zachariassen and Helfer (2017) on what makes or breaks national dialogues, Guo et al. (2015) on understanding national dialogues, Blunck and Vimalarajah (2017) in their national dialogue handbook, among other scholars, there is a need to continue improving theories and practices for organising successful national dialogues. Murray and Stigant (2021) observe that critical national dialogue success factors include a clear mandate for the dialogue, a neutral convenor, inclusive participation and representation of diverse groups and interests, and a clear implementation plan of the dialogue’s agreed-upon decisions. A well-defined implementation plan “provides a strategic momentum beyond the dialogue itself” (Murray and Stigant, 2021:3). The authors echo similar findings from Paffenholz, Zachariassen and Helfer (2017) who discovered that while national dialogues are increasingly being used as political conflict resolution tools, only half of them have been successfully implemented. Based on seventeen national dialogue case studies, the author observed that there are six national dialogue success factors, which are: (i) representation and selection of actors; (ii) decision-making procedures; (iii) choice of mediators and facilitators; (iv) duration or timeframes of the national dialogue; (v) support structures for the national dialogue; and (vi) coalition-building among participating actors. While these success factors provide empirical insights on what to consider when designing national dialogues, there is little discussion of the theoretical frameworks underpinning the practice of national dialogues, except for inferences about the national dialogues’ transformative abilities.

Blunck and Vimalarajah (2017) provide a variety of national dialogue models where distinct success factors can be identified. Their guide offers a wealth of information on diverse national dialogue models, phases of national dialogues, and institutional structures and frameworks. In conceptualising national dialogues, the authors observe theoretical overlaps between the practice and study of peacebuilding. As a result, they labour to distinguish national dialogue from mediation and negotiation. This article, therefore, seeks to enhance theoretical precision of national dialogue conceptual frameworks by proposing a trifecta model combining the theories of social contract, conflict transformation, and consociationalism. National dialogues are not a panacea to national conflicts, rather, they are “part of a broader continuum of mutually reinforcing efforts that foster dialogue, forge agreements and drive towards peace” (Murray and Stigant 2021:3). This further justifies the need to continuously improve the theories and practices of national dialogues.

It is important, however, to point out that a national dialogue is an inadequate tool to address political crises and conflicts with a regional dimension, as is the case with Great Lakes conflicts covering Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Rwanda (Ford, 2024), as well as the Lake Chad Basin covering Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Niger (Nagabhatla et al., 2021). Addressing these regional conflicts would require a regional dialogue as opposed to a national dialogue. Nonetheless, the proposed conceptual framework — consociationalism, social contract, and conflict transformation — may still be applicable in designing a regional dialogue.

2.2 Towards a conceptual framework for national dialogues

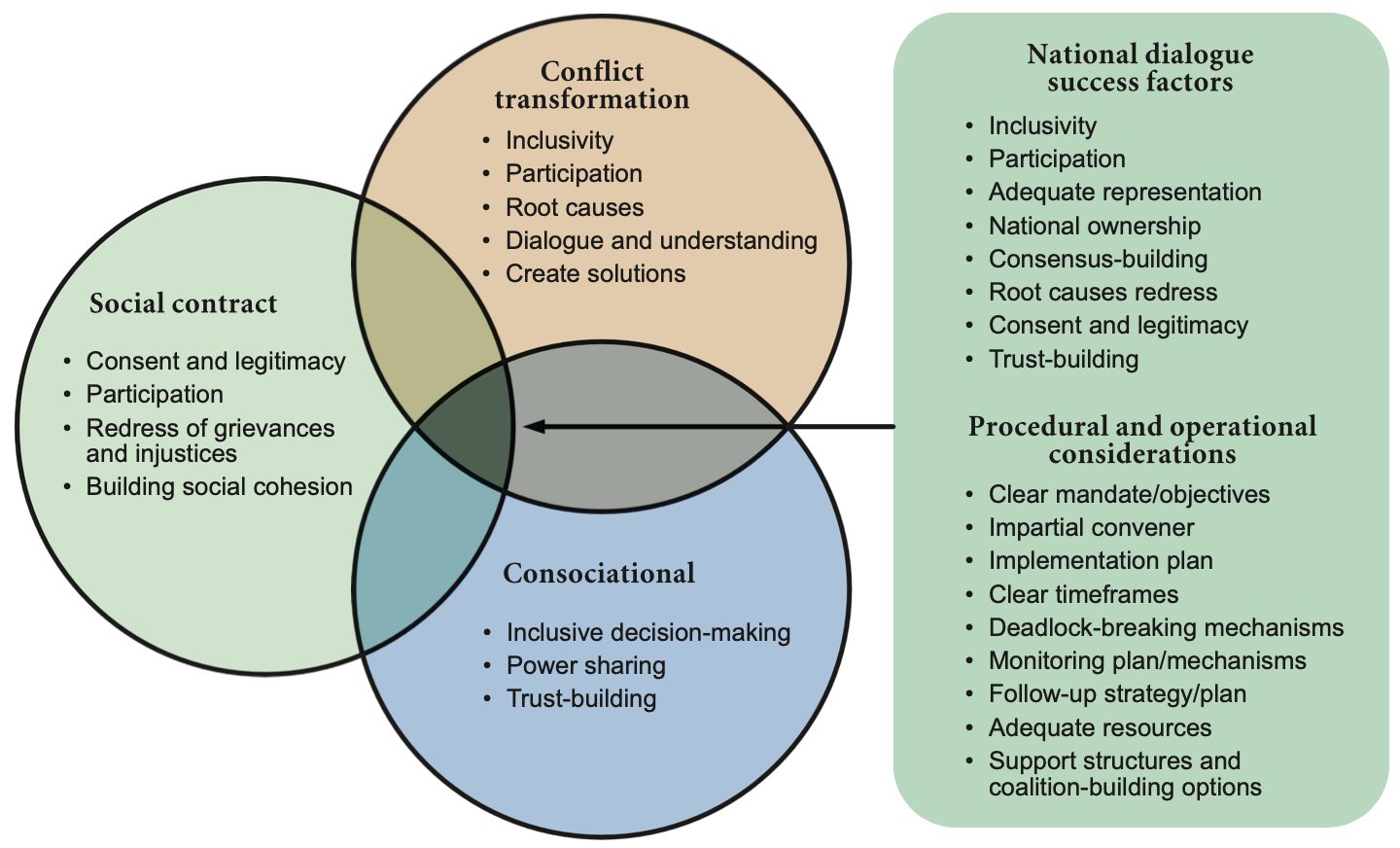

The concept of national dialogues does not have a standalone theory; it is founded on the notions of conflict prevention, management, and resolution. A general search of ‘national dialogue theory’ on research platforms such as Google Scholar, does not yield any related results. Hence, this article attempts to contribute towards the establishment of a national dialogue theoretical framework by using the consociational theory, conflict transformation theory, and the social contract theory. These three theories were chosen because their constitution involves elements essential in designing successful national dialogues, such as participation, inclusivity, impartiality, ownership, transparency, trust-building, consensus-building, and consent. The proposed theoretical framework is built on the work of Paffenholz, Zachariassen and Helfer(2017) on what makes or breaks national dialogues, Guo et al. (2015) on understanding national dialogues, and Blunck and Vimalarajah (2017) in their national dialogue handbook. The suggested framework acknowledges that national dialogues are not only events but also processes and outcomes of various actions, all intended to address national conflicts through an inclusive, participatory, and consensus-building approach. Figure 1 shows a visual depiction of the contributory concepts of consociationalism, conflict transformation, and social contract to national dialogue based on the author’s conceptualisation.

Figure 1: National dialogue theoretical framework

The three theories depicted in Figure 1 are essential in the design and implementation of national dialogues because they are all peacebuilding frameworks that provide valuable insights into conflict management and resolution.

2.2.1 Conflict transformation theory

The theory of conflict transformation is linked to national dialogues because both are applicable approaches to peacebuilding and conflict resolution at the national level. Conflict transformation is defined as “a process of engaging with and transforming the relationships, interests, discourses and, if necessary, the very constitution of society that supports the continuation of violent conflict” (Miall, 2004:4). It aims to “transform the events, people and relationships” through collaborative problem-solving means (Ercoşkun, 2021:6) — an objective that responds directly to the needs of national dialogues. The purpose of national dialogues, in part, is to transform perspectives of the conflicting parties by changing their attitudes and behaviours towards other conflict parties and the conflict itself (Pathak, 2016). This implies that dialogues are transformative, and the conflict transformation theory can be used to explain how dialogues transform perspectives.

The concept of conflict transformation is drawn from the seminal works of Johan Galtung (1996) and John Paul Lederach (1995), who are considered the fathers of peace studies (Botes, 2003; Ercoşkun, 2021). Both Galtung and Lederach view conflict as an opportunity to improve relations among conflict actors by transforming their personal, structural, and conflict issue perspectives. Hence, the theory of conflict transformation is a framework for understanding the management of conflicts, which proposes that conflicts can be opportunities for positive change and growth rather than merely destructive events to be avoided or resolved by force (Ercoşkun, 2021:6).

A deeper definitional analysis of the conflict transformation theory reveals its link to national dialogues. For example, Kriesberg (2011:50) defines conflict transformation as “the processes of transition to relatively non-destructive conduct and to a relationship between adversaries that is regarded as largely non-contentious”. In this definition, there are two clear-cut components: (i) transition from a destructive conflict situation to a non-destructive situation (conflict termination) and (ii) building a relationship between conflicting parties, including recovering from the trauma and hurt caused by the destructive conflict. These two elements are familiar in national dialogues in situations where dialogues are established to negotiate for the cessation of hostilities and later the establishment of a more sustainable relationship anchored on socio-political and economic reforms. Impliedly, therefore, the nexus of conflict transformation and national dialogue goes beyond just building the capacity of conflict actors to deal with their conflict, but to ensure systematic and structural changes in the conflict realm (Lederach, 2014).

National dialogues are increasingly seen as “seminal for the transformation of relationships, the promotion of empathy, and the rapprochement of particular groups after conflict” (Planta, Prinz and Vimalarajah, 2015:4). This is because they bring together diverse stakeholders at the national level to dialogue on specific issues that have an impact on peace and stability in the country. By ensuring that all voices are heard and represented, national dialogues foster inclusive decision-making and build consensus and legitimacy for the outcomes of the process. Thus, these dialogues position inclusivity (of diverse stakeholders) as a central element of transformative national dialogues. Inclusivity in national dialogues is transformative because it promotes more informed deliberations and deeper concurrences that lead to implementable and sustainable agreements. The transformation does not happen in only one space, but in multiple spaces, including transformations among actors, changes in the conflict issue, the perspectives about the conflict, and structures sustaining the conflict (Botes, 2003; Miall, 2004).

However, whereas national dialogues may be transformative, not all dialogues are transformative (Planta, Prinz and Vimalarajah, 2015). Some dialogues are intended to terminate conflicts without necessarily transforming the root causes of conflicts. For example, Zimbabwe’s national dialogue on the constitution focused on the immediate production of a new constitution without necessarily transforming the institutions that sustained bad governance and cultures of violence. Unsurprisingly, since 2013, when the new constitution was adopted, it has been mutilated several times, because the structures sustaining bad governance were not transformed during the constitutional reform processes.

Some national dialogues are also designed to benefit the incumbent leaders’ political interests at the expense of genuine political conflict transformation. For example, the Egyptian national dialogue, launched on 3 May 2023, was a one-sided and top-down initiative designed to protect the incumbent regime (Ottaway, 2023). Similarly, in the Gabonese 2024 national dialogue, the president allegedly “invited about 100 senior military officers and about 250 people who were loyal to the ousted Bongo regime” to ensure that the views from the national dialogue will perpetuate his stay in power (Kindzeka, 2024:1).

2.2.2 Social contract theory

The social contract theory emphasises that the consent of the governed should be central in decision-making, a notion applicable to the scope of national dialogues. ‘Social contract’ refers to the “entirety of explicit or implicit agreements between all relevant societal groups and their sovereign (i.e. the government or any other actor in power), defining their rights and obligations toward each other” (Loewe, Zintl and Houdret, 2021:3). Social contracts between the government and citizens, therefore, regulate state–society relations. Hence, national dialogues can be regarded as a mechanism used to redefine or renegotiate the social contract between the political actors, the citizens, and the government (Inclusive Peace & Transition Initiative, 2017; Odigie, 2017). This is because a national dialogue allows diverse stakeholders to present their grievances to a forum of other stakeholders seeking to reconfigure how they are governed by the state and how different state actors can participate in the social contract.

The notion of the social contract is derived from classical liberal writers such as Thomas Hobbes (1651), John Locke (1689), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762), and Hugo Grotius (1625). The social contract theory hypothesises that an agreement (formally or informally) between the state and citizens is good for socio-economic and political stability, hence facilitating sustainable peace and development. If the social contract breaks down, there will be conflict between the state and its citizens. For example, the breakdown of the social contract between citizens and their state in Tunisia, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and Libya resulted in the Arab Spring revolutions (Loewe, Zintl and Houdret, 2021). In these countries, renegotiation of social contracts came through national dialogues, among other mechanisms. The Yemen National Conference held between 2013 and 2014, for instance, was aimed at producing a new social contract, including constitutional and institutional reforms (Paffenholz and Ross, 2016). Equally, the Central Africa Republic’s (CAR) National Forum of Bangui held in 2015 aimed at defining “a new social contract between all layers of society of CAR via consensual, global and sustainable solutions” (Blunck and Vimalarajah, 2017:116). However, although the CAR national dialogue succeeded “in renegotiating the social contract through both armed group and citizen consultation”, it could not address the root causes of the conflict in the country (Murray and Stigant, 2021:34). The failure to address the root causes may be attributed to the lack of broad-based participation.

What defines the state–society social contract are the responsibilities and obligations between the government and the governed. The obligations of the state, through the government, include the provision of safety and security and social services, while the responsibilities of the citizens are to recognise the legitimacy of the government and to pay taxes, including complying with laws and regulations administered by the state. When both the state and the society adhere to the agreed rules and responsibilities, they create an equilibrium in state–society relations, hence strengthening social cohesion and stability (Loewe, Zintl and Houdret, 2021). However, if the state or the citizens fail to honour their obligations and responsibilities, the government collapses, and a social contract will require a renegotiation — a scenario in which a national dialogue fits. Hence, when designing national dialogues, it is important to consider the key elements of the state–society social contract, including safety / protection, provision of social and economic services, and participation of citizens in governance processes.

2.2.3 Consociational theory

This theory’s application to national dialogues is invaluable because it consciously promotes the inclusion of various groups in policy- and decision-making processes. Consociationalism is “a form of government applied in deeply divided societies which aims at achieving political stability” (Aboultaif, 2020:109) through power-sharing, and inclusive decision-making. The concept of consociationalism is drawn from the seminal work of Arend Lijphart (1977), who advances that for divided societies to maintain political stability and peace, they should practice consociationalism. This form of governance has four core features: government by executive power-sharing or grand coalition, mutual veto rights for diverse groups, proportionality, and community autonomy for each social segment (Lijphart, 1977; Aboultaif, 2020; Haughey and Loughran, 2024). It is, therefore, a conflict regulation mechanism for societies that are ethnically divided, politically polarised, and economically unequal. The concept’s applicability to African societies requires further investigation.

The assumption of consociationalism is that common policy issues should be decided by participation of many segments of the society while at the same time allowing minority groups deciding on their group-specific issues alone (Valentim and Dinas, 2024).

Bogaards, Helms and Lijphart (2019:342) maintain that “the value of consociationalism as a concept for peaceful conflict regulation increases with the degree of polarisation and division in a given society”. The same principle applies to calls for a national dialogue. Demands for national dialogues generally increase with more dissent, divisions, and deep polarisation among citizens along political competition, party politics, ideological differences, religious, economic, and social identity fault lines. For example, the call for a national dialogue in Ethiopia has been primarily attributable to the rising political insecurity, increasing identity politics, polarisation, and inequalities (Felek, 2024). This shows that factors that warrant the application of consociationalism are closely related to those warranting national dialogues.

However, it is important to note that consociational practice can be considered too elitist and become exclusive of grassroots groups and organisations (McGarry and O’Leary, 2006). Integrationist scholars such as Hayward (2015:592) argue that even though consociationalism could be regarded as too elitist, “peacebuilding should be pinned to the concept of consensus-building, given its insinuation of inclusivity.” Countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium are arguably peaceful because they include consociational policies in their governance processes to ensure that minorities are represented, have a voice, and can influence decisions (Wilkinson, 2000). In contrast, there are countries where consociationalism has completely failed because of elitism and dictatorship of the minority, as was the case in Lebanon and Iraq (Mako and McCulloch, 2024). In Lebanon, for example, consociationalism failed because it reinforced both horizontal and vertical inequalities (Makdisi and Marktanner, 2009:i). Some African countries characterised by political elitism and ethnicity may also fall into this category of failed consociational democracy. Hence, when designing national dialogues for success, consociationalism must be deliberately considered, but without promoting segmental elite dominance or coerced consociationalism in the national dialogue process.

3. Pretesting the framework: Zimbabwe’s political dialogue actors

Zimbabwe is an ideal test case for the proposed national dialogue conceptual framework because of the country’s prior experience with national dialogues. Zimbabwe has experienced national dialogues characterised by inter-party dialogues and broad-based citizen-inclusive dialogues. These initiatives were largely prompted by the country’s severe political polarisation, which was marked by instances of grave politically motivated violence and severe economic challenges (Moyo and Helliker, 2023). Political polarisation in Zimbabwe poses a significant obstacle to achieving lasting peace and socio-economic progress. Among many other attempted national dialogues, the country’s most recent national dialogue efforts occurred in 2019 when POLAD was established (Musendekwa, 2024). Prior to POLAD, other dialogues worth noting, include the 2008–2009 coalition government dialogue leading to the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU), the constitutional dialogues mooted in 2009 leading to the adoption of a new constitution in 2013 (Nhengu and Murairwa, 2020; Musendekwa, 2024), and the inter-party dialogue held in 1987 leading to the Unity Accord (see Banana, 1989; Mashingaidze, 2005).

POLAD was established as a national dialogue platform, in response to the country’s highly contested 2018 presidential election results and “an intensified political crisis triggered by fuel price hikes, leading to countrywide protests from 14 to 16 January 2019” (Mandikwaza, 2019:21). The platform brought together the ruling ZANU PF party and 17 fringe political parties that had participated in the 2018 elections but without the main opposition party, the MDC-Alliance (Ndoma, 2020; Marongwe, Duri and Mawere, 2022; Mazorodze, 2023). Symptomatically, POLAD was an inter-party-political conflict transformation platform aimed at facilitating a peaceful resolution of the hanging 2018 electoral disputes, the fatal post-election military shootings of protestors, and the general demand for socio-economic and political reforms.

When President Emmerson Mnangagwa launched POLAD in May 2019 as a national dialogue process, he emphasised that the platform’s goal was to facilitate a peaceful resolution of conflicts through dialogue, positive engagement, and mutual agreement (Ndoma, 2020). This evidently implies that POLAD was a space for conflict transformation, bringing together political parties as citizens’ representatives. However, the most significant problem in designing this conflict transformation space was that POLAD excluded the major opposition party, the MDC-Alliance, in favour of smaller opposition parties that became key players in the dialogue. Before the formation of POLAD, Brian Kagoro had warned that the ruling party and government needed to understand that “none of the contending forces can survive if they do not take immediate action to minimise institutional, political, social and economic pressure that they are independently faced with” (Kagoro, 2018:1). Hence, a genuine national dialogue capable of transforming the country’s socio-economic and political fortunes required good faith, committed mutual trust, and a truly impartial and powerful mediator. The ruling party did not consider these conflict transformation tenets when designing the national dialogue process, which is why POLAD failed to prevent subsequent electoral and political disputes. More precisely, the POLAD dialogue platform failed to gain acceptance from all parties involved in the post-election conflict, raising questions about its political legitimacy. This undermined its credibility and trustworthiness among the main opposition party, civil society, and the general populace (Dendere and Taodzera, 2023; Musendekwa, 2024).

The Zambian National Dialogue Forum, established in 2019 by the ruling Patriotic Front, encountered similar legitimacy challenges that led to its disapproval from opposition parties, civil society organisations, and religious groups (Mukunto, 2021). The legitimacy of a national dialogue platform is pivotal in determining its ability to effect behavioural and attitudinal transformation among conflicting parties. In conflict transformation theory, legitimacy in national dialogue helps to build trust, encourage participation, promote inclusive participation, and ensure the acceptance of both the dialogue process and its outcomes. This, in turn, facilitates a shift in attitudes and behaviours among conflicting parties, encouraging them to engage in collaborative problem-solving.

The establishment of POLAD, in part, was to cure the social contract legitimacy crisis between the government and citizens because of the contested 2018 presidential election results. In establishing POLAD, one of the conditions put forward was that parties must accept Emmerson Mnangagwa as Zimbabwe’s legitimately elected president (Mazorodze, 2023). The precondition implied that consent would be obtained from political parties and citizens by force, and that refusal to give consent would result in the loss of the right to participate in POLAD’s national dialogue process. Beyond political parties, the general Zimbabwean population disapproved of POLAD because of its lack of inclusivity. In a 2021 survey, for example, only 28 per cent of 1,200 respondents identified POLAD as the only option for promoting political stability and development in Zimbabwe. When asked about POLAD’s need for inclusivity, 73 per cent of the respondents concurred that the national dialogue platform was not inclusive, indicating the need for an inclusive national dialogue beyond political parties (Afrobarometer, 2021). Arguably, the government should have considered the social contract theory in designing the POLAD process to ensure that consent and legitimacy are genuinely sought and that the people’s grievances are addressed.

Adequate representation and inclusive participation are cardinal success factors in national dialogues. Yet POLAD was extremely exclusive of the main political actor, the MDC-Alliance party and by extension the civil society. The heads of the Civil Society Coalition observed that the POLAD national dialogue process was discriminatory and exclusive, and they argued that the civil society, political and religious leaders, the diaspora community, and the victims and their families affected by the country’s socio-economic and political violations should be included (Ndoma, 2020). However, the government continued with the POLAD platform without heeding the national dialogue stakeholders’ calls. As a result, POLAD failed to achieve any material results, including the much-envisaged political and economic reforms because it remained exclusive, partisan, and controlled by the ruling party (Gumbo and Shava, 2021).

POLAD was also established without regard for consociationalism; yet the country has visible ethnic social divisions characterised by unequal access to resources, development, and inclusion in national decision-making processes. For example, the people of Matabeleland have a genuine historical grievance of both political annihilation and economic marginalisation, but their issues were never included in POLAD’s conflict transformation agenda; yet their grievances remain a thorny national healing and reconciliation issue for Zimbabwe (Reim, 2023). In fact, “the convergence of grievance and resentment among various groups and constituencies has thus given rise to highly ethnicised politics in Zimbabwe” (Muzondidya and Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2007:293) such that any future national dialogue must take consociationalism into account to avoid excluding minority groups’ grievances.

Prior to POLAD, in 2008, Zimbabwe had experienced a successful national dialogue process that culminated in the formation of a GNU in 2009, following a disputed presidential election marred by political violence (Raftopoulos, 2013). This dialogue was an inter-party negotiation involving three political parties embroiled in the electoral results dispute: ZANU PF and two factions of the Movement for Democratic Change — MDC-Tsvangirai (MDC-T) and MDC-Mutambara (MDC-M). The success of the national dialogue can be attributed to its adherence to conflict transformation principles, resulting in the signing of the Global Political Agreement (GPA) and the formation of a coalition government in 2009. However, the dialogue failed to incorporate consociational and social contract theories, thereby marginalising citizens, civil society, and the churches in shaping the desired coalition government. Arguably, this oversight was detrimental, as it may explain the incomplete implementation of the GPA, with ZANU PF reneging on its obligations.

Coalition governments arising from genuine national dialogues should be inherently inclusive of both political and non-political actors. This inclusivity is essential because such governments, by design, are conflict transformation mechanisms “adopted to effect relief from conflict and suspend hostilities among raging political and non-political actors” (Nhengu and Murairwa, 2020:48). Hence, if the coalition dialogue had extended its inclusivity to various actors beyond political parties, robust implementation and monitoring mechanisms would have been entrenched. This broader engagement might have mitigated ZANU PF’s unyielding influence, both during the dialogue process and within the GNU and led to sustained conflict transformation.

Nonetheless, the constitutional dialogue that formed part of the inter-party dialogues’ agreement (see Article VI of the GPA) involved a semblance of the proposed conceptual framework, including the notions of conflict transformation, consociationalism, and the social contract. The constitutional dialogue, initiated between 2009 and 2013, applied the design of national consultations allowing citizens, civil society, churches, and political parties to participate in the constitution-making process. It was an inclusive process with a high-level degree of legitimacy, although the process drew criticism for being overly controlled by the three parties in the coalition government. Arguably, the constitution-making process demonstrated an inclusive consensual dialogue process allowing diverse actors to engage in transformative, sound conversations that extended beyond the influence of political elites. This inclusivity may explain the high approval rate of the 2013 constitution, which received 93% support from 60% of the total electorate, in contrast to the 2000 draft constitution that was rejected by 54% of the 20% of the electorate who participated in the referendum (Sachikonye, 2013). The rejection of the 2000 constitution can be attributed to a lack of consensus among both citizens and elites involved in its preparation, as well as its failure to incorporate conflict transformation, consociational representation, and alignment with social contract principles.

The 1987 Unity Accord dialogue is spectacular for its attempt to incorporate both notions of consociationalism — by integrating the Shona and Ndebele ethnicities — with conflict transformation, aiming to resolve the political conflict between the nationalist parties, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) and ZANU. This dialogue was prompted by the violent campaign known as Gukurahundi, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 20,000 people between 1983 and 1987, predominantly in the Midlands and Matabeleland regions of Zimbabwe (Mashingaidze, 2005; Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Benyera, 2015). The dialogue led to the signing of the Unity Accord on 22 December 1987, which successfully merged the parties into a unified ZANU PF, effectively establishing a one-party state and bringing an end to the atrocities and hostilities.

However, the accord was widely criticised for appeasing the ruling party’s interests, and that it was an elite pact that side-lined citizens and civil society (Nkobi, 2011), a situation similar to the 2008 coalition government dialogue. The Gukurahundi affected communities were excluded from contributing to the contents of the Unity Accord and shaping their desired post-conflict justice initiatives. Had the government considered the notions of social contract, the affected communities and the general Zimbabwean citizens would have been consulted. Such an inclusive approach could have fortified the Unity Accord by addressing justice and reconciliation concerns, potentially preventing the Gukurahundiatrocities from continuing to haunt Zimbabwean society four decades later. This inclusive dialogue could have fostered a more unified Zimbabwe, with reduced ethnic-based political tensions and an increased demand for consociational democracy and a renegotiated social contract.

4. Conclusion

Overall, the three theories of social contract, conflict transformation, and consociationalism are essential in designing and implementing successful national dialogues. As noted earlier, to ensure that national dialogues are implemented successfully, there is a need for clear objectives of the dialogue process, inclusivity and participation of diverse groups, trust-building, consensus, and legitimacy of all decision processes. The national dialogue must strive to address not only existing conflict issues but the root causes of the crisis being addressed. These elements can best be addressed when the national dialogue designers consider the proposed conceptual framework integrating the social contract, consociational, and conflict transformation theories. The social contract theory highlights the consent of the governed, the consociational theory advocates for inclusive decision-making, and the conflict transformation theory emphasises dialogue and engagement among conflicting stakeholders, which are all important factors in good governance. All three theories emphasise the importance of inclusivity, inclusive decision-making, and collaborative actions towards social change; hence, they are eminently suitable to inform national dialogue design and implementation.

Reference List

Aboultaif, E.W. (2020) Revisiting the semi-consociational model: democratic failure in prewar Lebanon and post-invasion Iraq. International Political Science Review, 41 (1), pp. 108–123.

Afrobarometer. (2021) People’s development agenda, leaders’ performance, national dialogue, freedoms, and perceptions of social media. Findings from Afrobarometer Round 8 survey in Zimbabwe. Afrobarometer [Internet], 7 July. Available from: <https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/zim_r8_diss_2-mips-perform-etc_presentation_7jul21.pdf> [Accessed 13 February 2024].

Bahati, M. (2024) Umushyikirano 2024: National dialogue to discuss development, unity. The New Times [Internet], 13 January. Available from: <https://www.newtimes.co.rw/article/13734/news/politics/umushyikirano2024-national-dialogue-to-discuss-development-unity> [Accessed 19 February 2024].

Banana, C.S. ed. (1989) Turmoil and tenacity: Zimbabwe, 1890–1990. Harare, College Press.

Blunck, M. and Vimalarajah, L. (2017) National dialogue handbook: A guide for practitioners. Berlin, Berghof Foundation.

Bogaards, M., Helms, L. and Lijphart, A. (2019) The importance of consociationalism for twenty‐first century politics and political science. Swiss Political Science Review, 25 (4), pp. 341–356.

Botes, J. (2003) Conflict transformation: a debate over semantics or a crucial shift in the theory and practice of peace and conflict studies? International Journal of Peace Studies, 8 (2), pp. 1–27.

Cheeseman, N. (2019) Lunga erodes Zambia’s democracy. Mail & Guardian [Internet], 6 September. Available from: <https://mg.co.za/article/2019-09-06-00-lunga-erodes-zambias-democracy/> [Accessed 22 July 2024].

Dendere, C. and Taodzera, S. (2023) Zimbabwean civil society survival in the post-coup environment: A political settlements analysis. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 12 (2), pp.132–152.

Dialogue Society. (2023) Journal of Dialogue Studies. Dialogue Society [Internet], 11 November. Available from: <https://www.dialoguesociety.org/publication/journal-of-dialogue-studies/ > [Accessed 10 January 2024].

Ercoşkun, B. (2021) On Galtung’s approach to peace studies. Lectio Socialis, 5 (1), pp. 1–8.

Felek, M.Z. (2024) The 2022 Ethiopia’s first-ever national dialogue formation: analyzing challenges and prospects. Cogent Social Sciences, 10 (1), pp. 1–17.

Ford, R. (2024) Conflict in the Congo: A critical assessment of Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Senior Honors Thesis, Liberty University. Digital Commons [Internet] Available from: < https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2502&context=honors> [Accessed 22 July 2024].

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: peace and conflict, development and civilization. London, SAGE Publications.

Gumbo, T. and Shava, C.K. (2021) Application of Lederach’s conflict transformation theory by Zimbabwe Council of Churches in national dialogue: an insider perspective. AfriFuture Research Bulletin, 1 (2), pp. 134–147.

Guo, X. et al. (2015) Understanding national dialogues. New York, Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA).

Haughey, S. and Loughran, T. (2024) Public opinion and consociationalism in Northern Ireland: towards the “end stage” of the power-sharing lifecycle? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 26 (1), pp. 187–207.

Hayward, K. (2015) Conflict and consensus. In: Wright, J.D. ed. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Oxford, Elsevier. pp. 589–583.

Inclusive Peace & Transition Initiative (IPTI). (2017) What makes or breaks national dialogues? Inclusive Peace & Transition Initiative [Internet], October. Available from: <https://www.inclusivepeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/report-national-dialogues-en.pdf> [Accessed 2 February 2024].

Kagoro, B. (2018) Zimbabwe: what are the realistic chances for political dialogue in Zimbabwe? The Zimbabwe Independent, 7 December, p. 12.

Kindzeka, M. (2024) Gabon opens national dialogue to bring country to civilian rule. Voice of America [Internet], 2 April. 2024. Available from: <https://www.voanews.com/a/gabon-opens-national-dialogue-to-bring-country-back-to-civilian-rule/7553797.html> [Accessed 24 July 2024].

Kriesberg, L. (2011) The state of the art on conflict transformation. In: Austin, B., Fischer, M. and Giessmann, H.J. eds. Advancing conflict transformation. The Berghof handbook II. Opladen / Framington Hills, Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Lederach, J.P. (1995): Preparing for peace: conflict transformation across cultures. Syracuse, Syracuse University Press.

Lederach, J.P. (2014) The little book of conflict transformation. Good Books, New York.

Lijphart, A. (1977) Democracy in plural societies: A comparative exploration. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

Loewe, M., Zintl, T. and Houdret, A. (2021) The social contract as a tool of analysis: introduction to the special issue on “Framing the evolution of new social contracts in Middle Eastern and North African countries”. World Development, 145,p. 104982.

Lumina, C. (2019) Zambia’s proposed constitutional amendments: sowing the seeds of crisis. African Network of Constitutional Lawyers (ANCL) [Internet], 29 November. Available from: <https://ancl-radc.org.za/blog/zambias-proposed-constitutional-amendments-sowing-the-seeds-of-crisis> [Accessed 22 July 2024].

Makdisi, S. and Marktanner, M. (2009) Trapped by consociationalism: the case of Lebanon. Topics in Middle Eastern and North African Economies, 11, pp. 1–15.

Mako, S. and McCulloch, A. (2024) Afterword: consociationalism and the state: situating Lebanon and Iraq in a global perspective. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 30 (1), pp. 164–172.

Mandikwaza, E. (2019) Constructive national dialogue in Zimbabwe: design and challenges. Conflict Trends, 2019 (1),pp. 20–28.

Marongwe, N., Duri, F. and Mawere, M. eds. (2022) Morgan Richard Tsvangirai’s legacy: opposition politics and the struggle for human rights, democracy and gender sensitivities. Cameroon, Langaa RPCIG.

Mashingaidze, T. (2005) The 1987 Zimbabwe National Unity Accord and its aftermath: a case of peace without reconciliation. From national liberation to democratic renaissance in Southern Africa. National Transitional Justice Working Group [Internet]. Available from: <https://ntjwg.uwazi.io/api/files/1549871826637gx19ui5kjul.pdf> [Accessed 24 July 2024].

Mazorodze, W. (2023) Political leadership in Zimbabwe in the aftermath of the military coup. Change without change? In: Chari, T. and Dzimiri, P. eds. Military, politics and democratization in Southern Africa: The quest for political transition. Cham, Springer. pp. 53–81.

McGarry, J. and O’Leary, B. (2006) Consociational theory, Northern Ireland’s conflict, and its agreement. Part 1: What consociationalists can learn from Northern Ireland. Government and Opposition, 41 (1), pp. 43–63.

Miall, H. (2004) Conflict transformation: a multi-dimensional task. In: Austin, A., Fischer, M. and Ropers, N. eds.Transforming ethnopolitical conflict: The Berghof handbook. Berlin, Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management. pp. 67–90.

Mosharraf, Z. (2020) Urgent: a grand national dialogue. The News International [Internet], 8 December. Available from: < https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/755297-urgent-a-grand-national-dialogue> [Accessed 24 February 2024].

Moyo, G., and Helliker, K. eds. (2023). Making politics in Zimbabwe’s second republic: The formative project by Emmerson Mnangagwa. Cham, Springer Nature Switzerland

Mukunto, K.I. (2021) National dialogue and social cohesion in Zambia. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 21 (2), pp. 58–80.

Murray, E. and Stigant, S. eds. (2021) National dialogues in peacebuilding and transitions: creativity and adaptive thinking. Peaceworks. Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace.

Musendekwa, M. (2024) Strides and struggles of coalition governments in southern Africa: The case for Zimbabwe. In Hishonga, T.S. ed. Enhancing democracy with coalition governments and politics. Pennsylvania, IGI Global. pp. 172–187.

Muzondidya, J. and Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2007) “Echoing silences\”: Ethnicity in post-colonial Zimbabwe, 1980–2007. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 7 (2), pp. 275–297.

Nagabhatla, N. et al. (2021) Water, conflicts and migration and the role of regional diplomacy: Lake Chad, Congo Basin, and the Mbororo pastoralist. Environmental Science & Policy, 122 (1), pp. 35–48.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. and Benyera, E. (2015) Towards a framework for resolving the justice and reconciliation question in Zimbabwe. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 15 (2), pp. 9–33.

Ndoma, S. (2020) Untangling the Gordian knot: Zimbabwe’s national dialogue. In: Masunungure, E. ed. Zimbabwe’s trajectory: stepping forward or sliding back? Harare, Weaver Press and Mass Public Opinion Institute.

Nhengu, D. and Murairwa, S. (2020) The efficacy of governments of national unity in Zimbabwe and Lesotho. Conflict Trends, 2020 (1), pp. 47–56.

Nkobi, Z. (2011) Post-independence politics. South African History Archive (SAHA) [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.saha.org.za/zapu/post_independence_politics.htm> [Accessed 23 July 2024].

Odigie, B. (2017) Regional organisations’ support to national dialogue processes: ECOWAS efforts in Guinea. Conflict Trends, 2017, pp. 20–28.

Ottaway, M. (2023) Egypt launches a one-sided national dialogue. Wilson Center [Internet], 1 May 2023. Available from: <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/egypt-launches-one-sided-national-dialogue> [Accessed 19 February 2024].

Paffenholz, T., and Ross, N. (2016). Inclusive political settlements: new insights from Yemen’s national dialogue. PRISM, 6(1), 198–210

Paffenholz, T., Zachariassen, A. and Helfer, C. (2017) What makes or breaks national dialogues? Geneva, Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative and the Graduate Institute of International Development.

Papagianni, K. (2014) National dialogue processes in political transitions. Civil Society Network Discussion Paper No. 3.Brussels, Civil Society Network.

Pathak, B. (2016) Johan Galtung’s conflict transformation theory for peaceful world: top and ceiling of traditional peacemaking. Transcend Media Services [Internet], 29 August. Available from: < https://www.transcend.org/tms/2016/08/johan-galtungs-conflict-transformation-theory-for-peaceful-world-top-and-ceiling-of-traditional-peacemaking/> [Accessed 19 March 2024].

Planta, K., Prinz, V. and Vimalarajah, L. (2015) Inclusivity in national dialogues: guaranteeing social integration or preserving old power hierarchies? IPS Paper No. 1, Inclusive Political Settlements.

Raftopoulos, B. (2013) The 2013 elections in Zimbabwe: the end of an era. Journal of Southern African Studies, 39 (4), 971–988.

Reim, L. (2023) “Gukurahundi continues”: violence, memory, and Mthwakazi activism in Zimbabwe. African Affairs, 122 (486), pp. 95–117.

Sachikonye, L.M. (2013) Continuity or reform in Zimbabwean politics? An overview of the 2013 referendum: Briefing. Journal of African Elections, 12 (1), 178–185.

Valentim, V. and Dinas, E. (2024) Does party-system fragmentation affect the quality of democracy? British Journal of Political Science, 54 (1), pp. 152–178.

Wilkinson, S.I. (2000) India, consociational theory, and ethnic violence. Asian Survey, 40 (5), pp. 767–791.

Yohannes, D. and Dessu, M.K. (2020) National dialogues in the Horn of Africa: lessons for Ethiopia’s political transition. East Africa Report. Addis Ababa, Institute for Security Studies (ISS).