Abstract

This article examines the dynamics of the connections between the nationalist government of Zimbabwe and the armed forces, which have translated into serious politicisation of the security sector and heavy militarisation of politics in the country. What has emerged in Zimbabwe is a clear nationalist-military oligarchy as a form of government. The question is: When did this nationalist-military oligarchy emerge? What are its dynamics and implications for governance in Zimbabwe? This article grapples with these fundamental questions in an endeavour to contribute to the on-going and animated debate on the crisis of governance in Zimbabwe in the 21st Century.

Introduction

On the 28th of December 2005, the then president of the main opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), Mr. Morgan Tsvangirai1 wrote a letter to President Robert Mugabe, which was copied to the Chairman of the African Union (AU), the Secretary General of the United Nations (UN) and the Chairman of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), complaining about how Robert Mugabe and the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) have transformed the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) and the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) ‘into combative political units of your party ZANU PF.’ Mr. Tsvangirai’s letter went on to highlight how the President of Zimbabwe as the Commander-in-Chief of the ZDF and as State President has violated the Zimbabwean constitution through politicisation of the armed forces. His letter is worth quoting at length because it encapsulates the whole problem of politicisation of the security sector and the militarisation of politics as well as the dangers of these processes to democracy and the future of civilian government in Zimbabwe. Beginning his letter, Mr. Tsvangirai stated that:

As the Commander-in-Chief of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF), you are no doubt acutely aware of the Constitutional provisions and the relevant Acts of Parliament governing the conduct and operations of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) and the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP). There are neither constitutional nor legal provisions in either the Constitution or the Defence Act and the Police Act which empower you to transform these national institutions into combative political units of your political party ZANU PF. Instead, in the Constitution and relevant Acts of Parliament, an impregnable line is clearly drawn between the areas of military operations and competence and those that are within the province of competence of political and civic authorities. You are constitutionally bound to maintain and uphold the line. Where the line is drawn is not a matter of interpretation, argument or haggling. The line is cast in stone. To equivocate on this fundamental principle is to overthrow a critical provision of the constitution and subvert the relevant Acts of Parliament. The ZDF and the ZRP are specifically and explicitly barred from participating in politics and political process of the country as organized units with distinctive preferences operationalised in the context of military and police formations aligned to a particular political party. They can participate in politics as individual private citizens entitled to cast their votes in secrecy of the ballot box. This line between military and political/civil matters is designed to ensure the perpetuation of representative civilian government as opposed to the imposition of an unrepresentative military junta. For the record, I have stated that under an MDC government, the professional standing, hierarchy and integrity of the Army and the Police will be jealously guarded. The Army and the Police will be insulated from the negative effects of competitive politics on their esprit de corps (Tsvangirai 2005).

For the purposes of democracy and the canons of constitutionalism, Tsvangirai’s letter is vital because it directly tries to protect the constitution as the supreme governing instrument in Zimbabwe. Secondly, it alludes to the importance of separating military and civilian issues. Thirdly and more importantly, it raises some concerns about the danger of creating conducive environment for a military junta in Zimbabwe.

This takes us to the fundamental question of how the civilian government mobilised resources and mechanisms to protect themselves from their own security forces and how ruling elites have succeeded in keeping the military on its side, but against the people. Zimbabwe under ZANU-PF has seen the ruling nationalist elite succeeding in politicising the army and the police and using these national institutions against the civilian population and opponents since the achievement of independence in 1980. Simon Baynham has underscored the fact that ‘clearly, this is a subject of key importance but one that has received inadequate attention in the study of African political affairs’ (Baynham 1992:5).

In Zimbabwe, a strong alliance between ZANU-PF nationalist leadership and the military forces has stood at the road to democracy and post-nationalist dispensation. It has guarded the nationalist shrine up to today and has defined politics in terms of a straight-jacket that only fits those with nationalist and military background. The latest causality has been the embers of democracy and post-nationalist alternative that started burning in 2000. These have been beaten back by threats and actual violence unleashed on the democratic train by the armed forces (regular ones) in collaboration with irregular quasi-military elements, both in support of the ruling ZANU-PF nationalist regime. This is a point made clearly by Tsvangirai in his letter when he said:

Tragically, the record of your regime displays a deliberate strategy to bend the Constitution and warp the relevant Parliamentary statutes in order to obliterate this critical separation between civilian and military affairs, as a way to thwart and neutralize legitimate and peaceful democratic political change. In the result, you have now created a civil-military junta, which acts as an illegal bulwark against democratic political opposition in general. This is amply demonstrated by the undeniable fact that since 2001, you have remained silent when members of the ZDF and ZRP officer corps make public political pronouncements singling out the MDC as an enemy political formation that must be destroyed, while at the same time, the same officers profess unqualified allegiance to your political party, ZANU PF (Tsvangirai 2005).

Indeed the military forces in Zimbabwe, particularly the senior officers, have not hidden their partisan dispossession in the political landscape of the country. For instance, in December 2001 General Vitalis Zvinavashe, then overall commander of the ZDF, flanked by the commanders of the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA), Airforce, Police and the Directors of the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) and Prisons, openly announced, at a televised press conference, their partisan and unequivocal allegiance to ZANU-PF. They went on to threaten a military takeover if another party other than ZANU-PF won the presidential elections. This action of the military commanders more than any other incident convinced many people that there was indeed an unbreakable umbilical cord between ZANU-PF nationalist elites and the military and that the military had transformed itself into a willing instrument of a particular political party and a particular presidential candidate.

The military commanders’ open declaration of their intention to negate popular will if it happened to be against ZANU-PF amounted to a threat to the constitutionally guaranteed provisions and democracy at large. Since 2000, a significant number of military commanders have uttered political statements favourable to ZANU-PF and threatening to those challenging ZANU-PF’s more than twenty five years rule over Zimbabwe.

Dangers of Involving the Military in Politics: Some Theoretical Issues

The legendary Napoleon Bonaparte’s maxim that without an army there is neither independence nor civil liberty is countered by Edmund Burke’s warning that an armed disciplined body is in essence dangerous to liberty. Indeed, armies use coercive force to achieve their objectives. The military has three main advantages over civilians. Firstly, superiority in organisational unity. Secondly, it has a highly emotional symbolic status. Finally and more importantly, it has superiority in the means of applying force (Finer 1962:6). Baynham emphasised the fact that since the military has an ‘effective monopoly in the organized use of force’ they should utilise this power in a responsible manner for the benefit of society, rather than in an uncontrolled and self-serving fashion. He proceeded to add that, in order to ensure that this takes place, most societies have insisted on the subordination of the armed forces to the political authority of the day (Baynham 1992:1). However, in Zimbabwe the issue of subordinating the armed forces to the authority of the day has taken a dangerous twist with grave consequences for the future of civilian government.

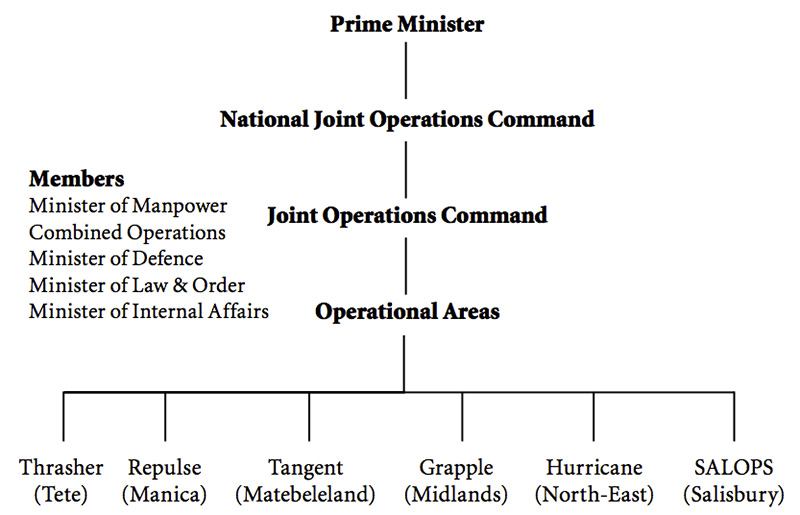

Due to the exigencies of fighting a protracted war of liberation from settler colonialism, the ruling ZANU-PF party operated as a quasi-military organisation. Since the early 1970s when the armed liberation struggle started, ZANU-PF (then known as ZANU only) never lost its military attributes. It became a party of civilian nationalist politicians and armed nationalist indoctrinated guerrillas. On the Rhodesia settler colonial side, the exigencies of counter-insurgency gave too much power to the Commander of the Combined Operations, General Peter Walls. Figure 1 shows the Rhodesian military structure in the period 1977–1979:

Figure 1: Rhodesian Military Structure, 1977–1979 Prime Minister

By the time of the ceasefire, the civilian leadership of Rhodesia had given over total control of military matters to Peter Walls to the extent that he was part and parcel of the delegation that negotiated the transition to independence at the Lancaster House Conference in Britain (Morris-Jones 1980, Bhebe & Ranger 1995, Stiff 2000).

Both ZAPU and ZANU civilian politicians fought hard from the 1970s to put those with military training under their control. The young military officers were indeed beginning to challenge the civilian leadership of the nationalist movement. The notable incidents – that were greeted with violence, detention, and/or co-optation – being the 11 March Movement in ZAPU in 1971,2 the Nhari revolt in ZANU, and the Zimbabwe People’s Army (ZIPA) saga that affected both ZAPU and ZANU in the 1970s. All these incidents, of which details are available in Ngwabi Bhebe and Terence Ranger’s Soldiers in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War (Bhebe & Ranger 1995), mirrored and magnified a lurking duality of power between civilian nationalists and their military wings. The crushing of ZIPA was a clear testimony to the resilience and strategic guile of the old guard.

Guerrilla armies of ZAPU (ZIPRA) and ZANU (ZANLA) like other armies enjoyed the monopoly of applying force on civilians. Secondly, guerrilla armies were different from conventional forces in that they were highly politicised if not indoctrinated to the extent that they operated as military cum political units. They carried in their heads nationalist movements’ ideologies and they were the active recruiters of the masses on behalf of their nationalist parties. They had access to the masses and they played a fundamental role in politicising the peasants in rural Zimbabwe (Ranger 1985, Lan 1985, Kriger 1992, McLaughlin 1996). Thirdly, guerrilla armies were not confined to the barracks; rather they existed like ‘fish in water’ among the public, to borrow Mao-Tse Tung’s words. On this issue, Ruth First noted that once the armies stepped beyond the barracks to engage in public policy making, ‘they soaked up social conflicts like a sponge’ (1970:436). First here was referring to conventional forces that are normally confined to barracks, but her analysis is also very relevant to guerrilla armies of ZAPU and ZANU in Zimbabwe. Indeed both ZANLA and ZIPRA ‘soaked up social conflicts like sponges’ in rural Zimbabwe to the extent that they even tried to wipe out what they considered as ‘witches’ (Alexander et al 2000, Nhongo-Simbanegavi 2000).

It is important to note that because the guerrilla armies operated as military cum mini-politicians, they became interested parties in politics. All guerrillas had passed through both military and political education in the rear bases in Mozambique and Zambia. Thus, even though they were not directly involved in the political direction of the nationalist movement, some of them tried to assume the role of umpires – the ultima ratio regum – of how the nationalist movement was to operate and under what conditions and terms. ZIPA was a clear example of this trend in the nationalist movement. ZIPA guerrillas (an out-fit of both ZIPRA and ZANLA) tried to vigorously embrace the Marxist-Leninist philosophy ahead of their leaders, discarding factionalism and fight as a united force, and to embrace the armed liberation option as the only solution to the Rhodesian problem. This initiative by the guerrillas themselves with the support of the frontline states was not welcomed by the civilian leadership of the nationalist movement. There was fear of losing dominance to the military wings as well as the direction of the revolution. Hence, ZIPA was quickly crushed and labelled a reactionary initiative (Bhebe & Ranger 1995).

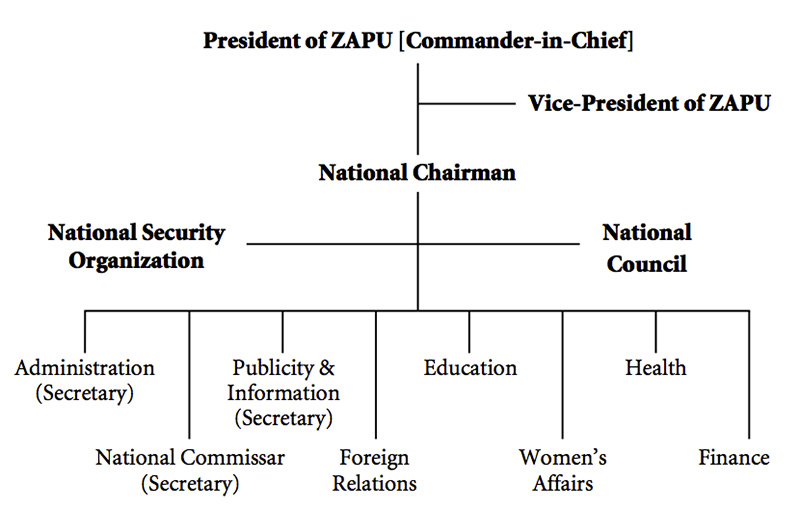

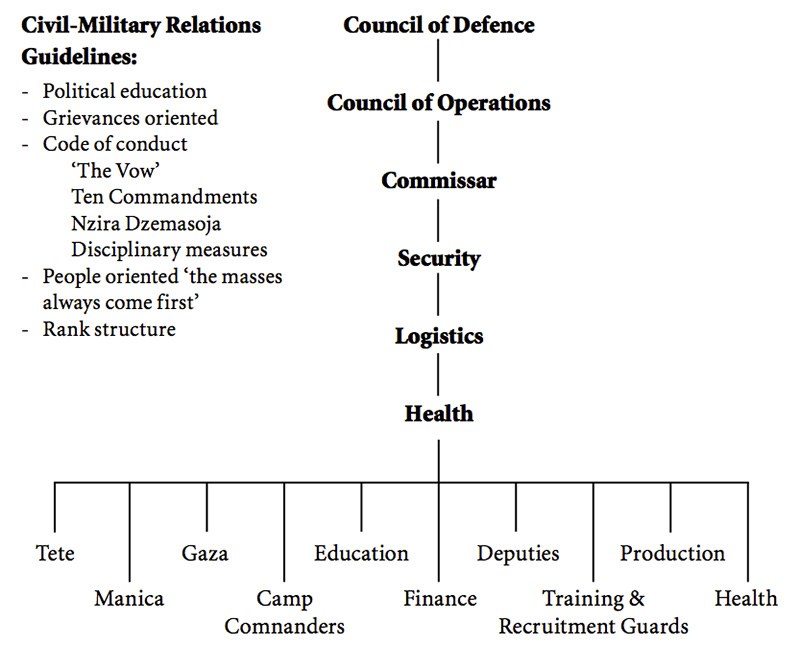

Efforts were taken in both ZAPU and ZANU to subordinate the armed guerrillas to the civilian nationalist leaders. First, the leaders of the parties elevated themselves to the High Commanders of the military wings. Secondly, the guerrilla leaders like General Josiah Tongogara in ZANU and Nikita Mangena (later Lookout Masuku) in ZAPU were integrated into the highest decision-making body of the nationalist movements (Politburo). Figure 2 on page 56 shows the ZAPU Political Structure.

Figure 2: ZAPU Political Structure

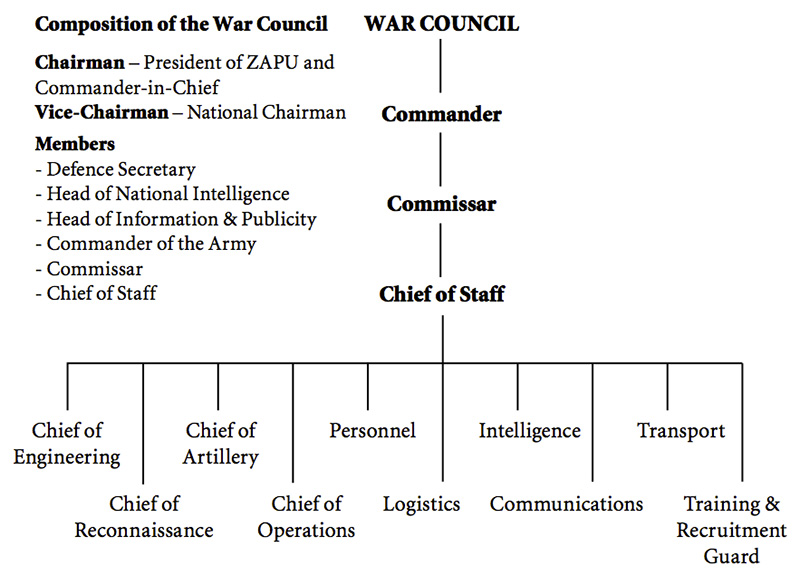

The fusion of the military and the political leadership in ZAPU is generally attributed to the Jason Ziyapapa Moyo document entitled ‘Observations on Our Struggle of 1976’. See Figure 3, which gives details on the fusion – if not the subordination of the military to the civilian political leadership of ZAPU. Ziyapapa was the deputy President and one of the key strategists of ZAPU before his assassination in 1976.

It was in the late 1970s that ZAPU created the Revolutionary Command Council as a representative body of party officials and military commandos. The War Council was the executive body that would take decisions emanating from Revolutionary Council discussions and was linked directly to the ZIPRA High Command. Efforts were made to unite the military and civilian nationalist aristocracy, to the extent that ‘The same men wore both hat and helmet’ (Nordlinger 1977:11). In this way, civilian nationalists won the day and civilian supremacy was maintained because the differentiation between military and non-military elites was very thin or insignificant to the extent that nationalist liberation war propaganda and ideology taught that all the leaders of the nationalist revolution were commanders of the military wings including those without any slightest military training and know-how.

Figure 3: ZIPRA Command Structure

Samuel P. Huntington applied himself fully to unravel the question of how civilian supremacy over military forces is achieved. He made a conceptual distinction between the ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ controls. When applied to guerrilla armies and nationalist liberation movements, Huntington’s models reveal interesting scenarios. Professionalism can be a disciplining factor to a military person, while patriotism and indoctrination can discipline a guerrilla fighter. The more patriotic the guerrilla fighters are, the more they would be prepared to serve the people and to die for them and the less of a threat they would pose to the nationalist leadership. Guerrilla armies were by and large constituted as political forces that operated under close party supervision (Huntington 1957).

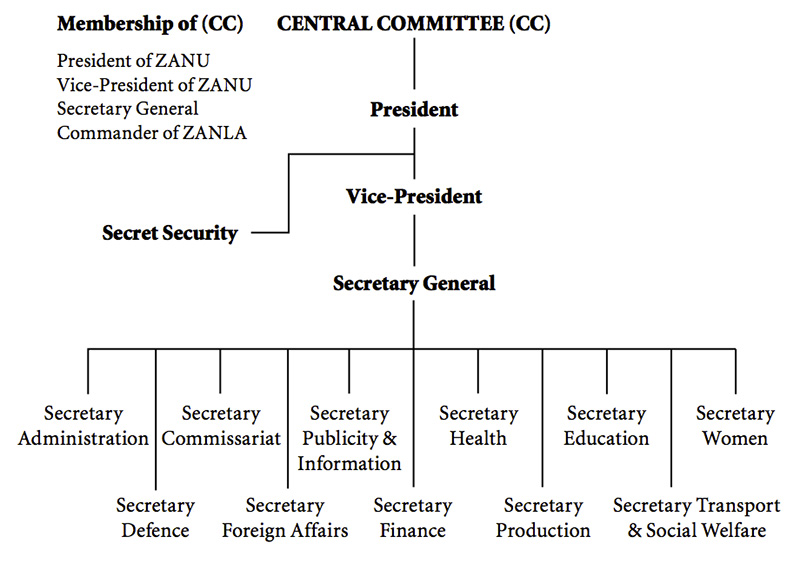

Eric Nordlinger’s penetration model is also very relevant to the understanding of the interaction between guerrillas and civilian nationalist leaders in Zimbabwe. Nordlinger emphasised the idea of civilian dominance that was ensured through the deployment of ideological controls and surveillance, founded upon a dual structure of authority in which military personnel were subordinated to political functionaries (Nordlinger 1977:11). In the case of ZANU and ZAPU, party commissars worked very hard in making sure guerrillas toed the party line (Nhongo-Simbanegavi 2000). See Figure 4 and Figure 5 on pages 59 and 60 respectively.

In the case of the ZANLA forces, they were expected to know ZANU party hierarchy to the extent that whenever they politicised the peasants their slogans followed a clear power line, starting with Pamberi na Comrade Robert Gabriel Mugabe (Forward with Comrade Robert Gabriel Mugabe). The civilian party leaders were literally worshipped by the rank and file of the party including the military forces. The party leader behaved as a super being and the messiah of the revolution. Terence Ranger argued that perhaps it was from this worship of the party leader that the post-colonial problem of personality cult was created (Ranger 2003).

Figure 4: ZANU Political Organisation, 1977–1980

At the end of the day one is forced to rephrase Samuel Huntington’s excellent theoretical intervention to read: ‘Subjective civilian control achieves its end by civilianizing the military, making it the mirror of the nationalist party. Objective civilian control achieves its end by militarizing the military, making them the tools of the ruling nationalist elite’ (Huntington 1957:83). [The italicised part is my rephrasing of Huntington’s statement to fit armies under nationalist regimes.]

Figure 5: ZANLA High Command

The new Zimbabwean state that emerged from the armed liberation struggle inherited highly politicised and highly indoctrinated military units. The Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF) were indoctrinated to believe that ZANLA and ZIPRA were terrorists and the latter believed that the former were colonial forces that needed to be disbanded. However, the exigencies of the compromise at Lancaster House dictated that these military units with different ideologies were to be integrated into a single Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA). This amalgamation of different military forces into a single national army takes us to the question of the character of the post-colonial Zimbabwean army.

The Character and Orientation of the Zimbabwean Military Forces

The Lancaster House Agreement of 1979 that gave birth to Zimbabwe in 1980 determined the character of the new army of Zimbabwe. The army was to be an integrated force of three major forces: ZANLA of Robert Mugabe, ZIPRA of Joshua Nkomo and the Rhodesian Security Forces of Ian Smith.

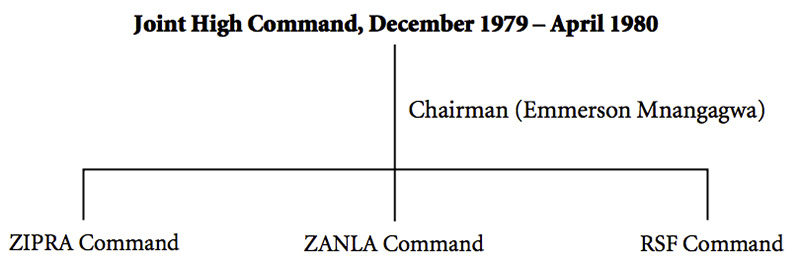

The stages in the integration of the three different forces included the formation of a Joint High Command (JHC) comprised of personnel from ZIPRA, ZANLA and RSF. The JHC emerged from the Ceasefire Commission. At the helm of JHC was the new Minister of State Security, Emmerson Mnangagwa. RSF Commander Lieutenant General (Lt. Gen.) Peter Walls was appointed commander of the JHC. His task was to implement the new defence policy, and manage the integration and conventional training that was to follow, while preparing to defend the state, the people and the country (Parliamentary Debates 1980:964). Wall’s colleagues (subordinates) in the JHC were senior commanders of the Rhodesian Air Force, ZANLA and ZIPRA. The idea was that it was necessary to demonstrate unity in the top echelons of military command in order to facilitate the same process in the middle of the military hierarchy, as well as among the rank and file (Chitiyo & Rupiya 2005:339). See Figure 6 for the transitional JHC structure:

Figure 6: Transitional Period

The integration exercise, however, was to be carried out within the context of tension in the country and among the military units themselves. For the first time, ZANLA, ZIPRA and RSF were to come nearer to each other. ZANLA and ZIPRA were expecting privileges as guerrilla forces that brought about the liberation of Zimbabwe. The Rhodesian forces looked at ZIPRA and ZANLA as ill-trained and unprofessional forces. ZIPRA and ZANLA expected to be transformed overnight into the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF). They believed that the Rhodesian forces were to be disbanded as a colonial force that oppressed the people (Interview with Leonard Ndlovu, Ex-ZIPRA). ZIPRA as a former military wing of PF-ZAPU was also agitated by the fact that their party (ZAPU) and their leader, Joshua Nkomo, had lost elections in 1980, while ZANLA forces were very happy that their party (ZANU-PF) and their leader (Robert Mugabe) had won the elections in 1980 (Mazarire & Rupiah 2000).

While the ZANLA forces sometimes accommodated ZIPRA forces as part of the liberation army, they were outrightly hostile towards the Rhodesian Security Forces. They also privileged themselves above ZIPRA whose leader and party had lost the chance to rule Zimbabwe. These tensions broke out into open military engagements, pitting together ZANLA against ZIPRA in Assembly Points (APs) of Chitungwidza, Connemara, Ntabazinduna, and Entumbane (Stiff 2000).

As the integration exercise was going on, the politicians were busy trying to solve and settle old scores. Inflammatory language was very common among ZANU-PF politicians who were so elated with electoral victory that they forgot that the major task of nation-building and the creation of a national army needed a sober thought. The most provocative ZANU-PF leaders were Enos Nkala, Edgar Tekere, Maurice Nyagumbo, Emmerson Mnangagwa, and Kumbirai Kangai (Catholic Commission for Justice & Peace, and Legal Resources Foundation 1997). PF-ZAPU’s response came through Josiah Chinamano, the Vice-President, who in early November 1980 alluded to the dangers of ZANU-PF slogans which had the effect of denigrating armed ZIPRA men. He referred to such slogans as Pasi ne Machuwachuwa (Down with ZIPRA) and Pasi ne vanematumbu (Down with those with big stomachs – a reference to Nkomo) (The Herald, 7 November 1980). Some ZANU-PF leaders took advantage of their electoral victory to settle scores with PF-ZAPU and the ZIPRA forces. PF-ZAPU and the ZIPRA forces were to be forced to accept that they were a junior force in the liberation struggle and Joshua Nkomo was to surrender the title ‘Father Zimbabwe’ (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2005).

Norma Kriger (2003) noted that from the start ZANU-PF wanted to build a party nation and a party state, crafted around and backed by its military wing (ZANLA). This was clearly demonstrated by the continued use of party slogans, party symbols, party songs and regalia at national ceremonies like Independence and Heroes Days (Kriger 2003:75). ZANU-PF and ZANLA moved quickly to occupy the centre of Zimbabwean political space immediately after independence. The national broadcaster, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC), was soon monopolised by the ruling party (ZANU-PF) and its war-time military wing (ZANLA). A concerted effort was made to de-legitimise and peripherise ZIPRA from the new ZANU-PF reconstructed liberation war history. ZIPRA was soon cast as a threat to the sovereignty of Zimbabwe, and its war-time commanders and the whole leadership of PF-ZAPU were reduced to ‘rabble-rousers and political malcontents who were still licking their wounds as a result of having lost the elections…’ (The Chronicle, 11 November 1981).

David Martin and Phyllis Johnson’s book The Struggle for Zimbabwe: Chimurenga War (1981) became the official master narrative of the liberation struggle that sidelined the other liberation forces and movements, elevating ZANU-PF and ZANLA to the centre of the whole nationalist history of Zimbabwe. This book was distributed to every secondary school in Zimbabwe, marking the beginning of partisan ethos in Zimbabwe.

While the policy of reconciliation adopted in 1980 emphasised unity in the country, the political actions of the ZANU-PF leaders compromised every aspect of this noble notion. ZANU-PF politicians behaved as though Zimbabwe was a one-party state. For instance, every Sunday morning up to the time of the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987, the programme, Dzimbo dzeChimurenga Dzakasunungura Zimbabwe (Chimurenga Songs that Liberated Zimbabwe) consisted of ZANLA songs only. This raised a lot of resentment from other people who felt that ZIPRA songs were supposed to be included too. One letter in the Herald of as far back as August 1980 protested against this bias, saying the songs were ‘…intended to suggest that ZANU (PF) alone fought and won the liberation war and this is a disgraceful distortion of history’ that seeks ‘to shun the visible reality that ZAPU (PF) exists and has fought as much as ZANU (PF) has done in the liberation war’ (The Herald, 21 August 1980). Since the end of the liberation war, ZIPRA mobilisation songs were not played on airwaves.

The broader issue of power struggles among Zimbabwean nationalists as well as factionalism that pre-dated 1980 is well treated in Masipula Sithole’s book Zimbabwe: Struggles Within the Struggle (Sithole 1999). What has not received adequate analysis were the implications and actual impact of this aspect of nationalist politics on the nature of the military that finally emerged in Zimbabwe. As noted by Horace Campbell, there were a number of questions raised by the prospect of integrating three distinct armies with different military traditions and differing perceptions of their role in the politically independent Zimbabwe. The pertinent question that dogged the ZANU-PF leadership and Robert Mugabe, in particular, as the Prime Minister and Minister of Defence was: What sorts of political control would be required to keep cohesion and discipline in the armed forces? (Campbell 2003).

The entire ZANU-PF leadership did not trust the former ZIPRA guerrillas as well as the former Rhodesian Security Forces.3 These two forces too were equally suspicious of ZANU-PF and former ZANLA forces’ intentions and plans. ZANU-PF politicians’ careless speeches worsened the fears among ex-ZIPRA and ex-Rhodesian forces. The first result of all this was demobilisation or early retirement of many white officers from the army. The second consequence was violent clashes between ex-ZIPRA and ex-ZANLA forces at the Assembly Points. The third impact was the demobilisation of a number of ex-ZIPRA forces from the army. The fourth result was a clear and sure move by ZANU-PF away from creating an integrated national army and towards making its war-time military wing the core of the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA).

This move was concretely indicated by the openly hostile official position towards ex-ZIPRA forces. Instead of being embraced as fellow liberation forces, they were largely viewed and ostracised as a nucleus of an alternative sovereignty, derived from the pre-colonial independent Ndebele state. They and their political leaders were seen in the same light as a potential source of counter-hegemonic alternative that needed to be crushed very quickly. Therefore, the clashes between ex-ZIPRA and ex-ZANLA forces were openly blamed on one side, that is ZIPRA, and their unwanted party, PF-ZAPU. Therefore, the discovery of arms caches in PF-ZAPU and ZIPRA-owned properties in 1982 was enthusiastically seized by ZANU-PF leadership as the clearest example and exhibit that ZIPRA and PF-ZAPU were planning to violently depose the democratically elected government of Zimbabwe under ZANU-PF.4 No wonder then that the discovery led to the crumbling of the veneer of the coalition government and the tenuous national unity (Catholic Commission for Justice & Peace, and Legal Resources Foundation 1997).

The leader of PF-ZAPU, Joshua Nkomo, was dismissed from the government following the discovery of the arms caches. The two former commanders of ZIPRA (Dumiso Dabengwa and Lookout Masuku) were arrested and detained on the grounds of plotting to topple ZANU-PF government. Other PF-ZAPU cabinet ministers were withdrawn from the Government of National Unity (GNU). As though this was not enough, widespread witch-hunts were conducted, targeting former ZIPRA combatants serving in the national army. Some terrified former ZIPRA combatants fled from the army to the bush, leading to swelling of ranks of the so-called ‘dissidents’. ZANU-PF found the needed pretext to deal once and for all with PF-ZAPU and ZIPRA. The fiery ZANU-PF cabinet minister, Enos Nkala, told a rally in Bulawayo that his party’s task ‘from now is to crush Joshua Nkomo’ whom he castigated as a ‘self-proclaimed Ndebele king’. From then onwards, Joshua Nkomo lost the title of ‘Father Zimbabwe’ and was given a new title, ‘Father of Dissidents’. His colleague in cabinet, Edgar Tekere, openly stated that he has been working to destroy PF-ZAPU and Joshua Nkomo since 1962 (The Herald, 4 July 1982).

From as early as 1981 ZANU-PF leadership was already busy building a partisan and highly politicised military force. There were two major justifications for it. First was the South African threat. Second was the existence of dissidents. While no one would deny that the dissidents needed to be dealt with, the questionable issue was whether this dissident menace required the building of another brigade on top of the integrated ZNA. The reality is that by this time Zimbabwe had excess military units to deal effectively with the dissidents. Was a specially trained brigade really needed? On 13 August 1981, Prime Minister Mugabe announced that a new military formation to be called ‘5-Brigade’ was being raised to be used ‘purely for the purposes of defence and not for use outside the country’. It would be used ‘solely to deal with dissidents and any other troubles in the country’ (Stiff 2000:93).

The formation of the Fifth Brigade (later to be known as Gukurahundi) marked the beginning of politicisation of the Zimbabwean military forces. The Fifth Brigade became a purely ZANU-PF army, operating outside the rank and file of the ZNA and directly answerable to Robert Mugabe. Mugabe clearly stated that ‘they [Fifth Brigade] were trained by the North Koreans because we wanted one arm of the army to have a political orientation which stems from our philosophy as ZANU-PF’ (Stiff 2000:93). Also, the formation of the Fifth Brigade marked the beginning of the ethnicisation of the Zimbabwean military forces. The Brigade was composed of former ZANLA elements and they all came from the Shona-speaking group in Zimbabwe.5 It must be noted that ZANU-PF enjoyed widespread support in Mashonaland. So this army was drawn from its base.

In the ranks of the ZNA, Shonalisation was taking place. The former ZIPRA and Rhodesian forces were demobilised in large numbers, leaving ex-ZANLA in place. Some ZIPRA who wanted to serve their country in the capacity of soldiers were harassed and threatened with death. Some just disappeared while serving in the ZNA. This forced more ZIPRA forces to demobilise (Interview with Jervious Moyo, ex-ZIPRA). Numerous incidents indicated the purging of ex-ZIPRA from the ZNA. A confidential British Military Advisory and Training Team (BMATT) document refers to the removal in August 1982 of ZIPRA from the Mechanized Battalion, a battalion in Second Brigade led by ZANLA’s Agnew Kambeu. The report states that: ‘The battalion was well integrated with 33 percent each of Former Army/ZANLA/ZIPRA and had a high standard of operational capability coupled with sensible and constructive training. However last month all ZIPRA elements (some 250) were removed and sent elsewhere which had reduced the battalion to a fairly poor state although the Former Army company is apparently still [in] being and tends to be used for demonstrations’ (Annex C to BMATT/1406, 3 September 1982). Norma J. Kriger’s book, Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe: Symbolic and Violent Politics, 1980-1987, is full of details on the purging of ZIPRA from the ZNA (Kriger 2003). Chitiyo and Rupiya (2005) also confirm the purging of ZIPRA which they trace to the arrest of ex-ZIPRA Commanders; Dumiso Dabengwa and Lookout Masuku in 1982, the removal of ZAPU officials from Cabinet in February 1982, which led to the collapse of the tripartite military power-sharing arrangement mooted in April 1980. Now only ZANLA senior cadres remained. Chitiyo and Rupiya (2005:341) add that: ‘Much more significantly, from henceforth there was little to stop the full implementation of a factionally based security policy in the country’.6

Unlike the South African Defence Force (SADF) that has continued to reflect the heterogeneous nature of the country after the fall of Apartheid, the ZNA quickly assumed a Shona dominance. There was no attempt at ethnic balancing in the military forces. Ethnicisation went in tandem with politicisation, leading to the emergence of a feared military force in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwean military forces are not a people’s army at all. The civilians fear their military forces (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2003). The military has been used to harass and kill the people of Matebeleland (1982-1987). University students and workers know the violence of the Zimbabwean military forces – be it the army or the police, they are both violent.

The Constitution, Military Forces and Civilians in Zimbabwe

Morgan Tsvangirai’s letter quoted at the beginning of this paper alluded to the violation of the constitution by President Robert Mugabe as the Commander-in-Chief of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. The claim made by Tsvangirai was that the army was misused by Mugabe in a power game. This provoked the need to analyse the constitutional framework governing the command-and-control of the army.

The 1997 revised National Defence Policy contains a clear hierarchy of governance, command and control of the military. President Robert Mugabe is the Commander-in-Chief of the ZDF and he chairs the State Defence Council.

The whole structure is presented in Figure 7 on page 70. The State Defence Council is the highest body responsible for national security affairs and its meetings are attended by ministers of defence, home affairs, foreign affairs and finance, as well as the commander of defence forces and the secretary for defence (Chitiyo & Rupiya 2005:347).

The constitutional framework guiding the ZDF is the national Constitution which underpinned the defence policies. It was elaborated further by the Defence Act. The Constitution provided a clear mechanism for superiority of civilian control over the military as well as public accountability of the military. The National Defence Policy makes it clear that ‘…civilian military relations refer to the hierarchy of authority between the Executive, Parliament and the Defence Force. A cardinal principle is that the Defence Force is subordinate to the civilian authority…’ (Government of Zimbabwe 1997:20).

According to the National Defence Policy, the civilian political authorities formulate defence policy and remain responsible for the political dimensions of defence, while the military executes that policy. It is also clearly stated that the civilian political authorities must respect military autonomy through non-interference with the operational chain of command and application of the military code of discipline. The president’s powers as Commander-in-Chief are:

- Determining the operational use of defence forces

- Determining the execution of military action

- Declaring of war

- Making peace

The President has power to appoint the Commander of the armed forces, and every commander of a branch of the defence forces, after consultation with a person or authority prescribed by or under an act of parliament. The President also appoints the Minister of Defence as the manager of the daily political functions of the military, and to whom the commanders report, except when they report directly to the President in cases of emergency (Government of Zimbabwe 1997).The parliament constitutes a vital military management structure and mechanism in that the ZDF structures are established by acts of parliament. Parliament makes provision for the organisation, administration and discipline of defence forces. Therefore ZDF is subject to the security and administration of regulatory parliamentary committees such as budget, public accounts and security. The judiciary comes in in cases of civil suits against the military (Chitiyo & Rupiya 2005:350).

Figure 7: Management of Defence Forces in Zimbabwe

| Structure | Members | Functions |

| Defence Council |

|

|

| Defence Committee |

|

|

| Defence Co-ordinating Committee |

|

|

Source: Government of Zimbabwe 1997.

According to the Zimbabwean constitution, military personnel are prohibited from active participation in politics. They are not allowed to hold office in any political party/political organisation. However, they can exercise their democratic right to vote as individuals (Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe).

The Third Chimurenga and Involvement of the Military in Politics

Despite the existence of noble legal and constitutional provisions for civilian control of the military and clear demarcation of military and political issues, the war-time civil-military relations legacy continued to subvert these structures. During the time of the liberation war, the military wings and the political parties were integrated into one politico-military organisation as represented in Figures 2-5 in this paper. Chitiyo and Rupiya (2005:350) noted that the ideology that political power comes from the barrel of the gun and that the gun is subordinate to the former is a notion that has since been transferred to the present governmental authority without fundamental re-orientation. This nationalist thinking was well articulated by Robert Mugabe long ago in 1976 when he tried to define the role of the military vis-í -vis electoral democracy. He said:

Our votes must go together with our guns; after all, any vote we shall have, shall have been the product of the gun. The gun, which produces the votes, should remain its security officer, its guarantor. The people’s vote and the people’s guns are always inseparable twins (Quoted in Maroleng 2005a:12).

According to Chitiyo and Rupiya, several generals are represented in the politburo, central committee or other ZANU-PF party structures. All this does not augur well for a professional and autonomous military and has far-reaching implications for democracy. Allying guns and votes symbolises a violent conception of electoral democracy.

The periods leading to the general elections of 2000 and presidential elections of 2002 were dominated by clear military intervention in civil affairs on behalf of the ZANU-PF regime. The reconstituted and rejuvenated war veterans association came into the centre stage of Zimbabwean politics. Its leaders gained access to the deadly military arms, which they enthusiastically used to intimidate people, while some of them even shot and injured civilians over political scores.7 The war veterans operated outside the purview of the Zimbabwean laws and were given a free hand to deal in any manner with those assumed to be opposed to ZANU-PF rule.

The fast-track land reform programme was spearheaded by the war veterans and was characterised by some of the most gruesome activities and atrocities. Some commercial farmers were shot in cold blood by people who supposedly had no right to use firearms. The war veterans set up detention and torture centres in the occupied farms where they dealt cruelly with anybody they suspected to be supporting the opposition party (Movement for Democratic Change, MDC).

The other group that entered the centre stage of politics in Zimbabwe was that of the Youth Militias (derogatively termed the Green Bombers due to their greenish military-style uniforms). The Militias, just like the war veterans, operated like Robert Mugabe and ZANU-PF’s storm troopers. They acted as the party’s eyes and ears. They erected roadblocks where they harassed people; asking them to produce ZANU-PF party cards as their travel and life passports in Zimbabwe. The National Youth Training Centres were established throughout the country and as stated by The Herald of 28 January 2002, the aim was ‘to instill unbiased history of Zimbabwe’ on all school leavers. According to the Solidarity Trust, teaching in the youth centres was crudely rudimentary and it elaborated that:

…there is overwhelming evidence that the youth militia camps are aimed at forcing on all school leavers a ZANU/PF view of Zimbabwean history and the present. All training materials in the camps have, from inception, consisted exclusively of ZANU/PF campaign materials and political speeches. This material is crudely racist and vilifies the major opposition party in the country … The propaganda in the training camps appears to be crude in the extreme. One defected youth reported how war veterans told trainees that if anyone voted for the MDC, then the whites would take over the country again … A youth militia history manual called ‘Inside the Third Chimurenga’ gives an idea of the type of ‘patriotism’ that is instilled in the camps. The manual is historically simplistic and racist and glorifies recent ZANU/PF National Heroes along with the land resettlement. It consists entirely of speeches made by President Robert Mugabe since 2000, among them addresses to ZANU/PF party congresses, his speech after the 2000 election result, and funeral orations for deceased ZANU/PF heroes… (Solidarity Peace Trust 2003).

The trained youth ended up as warriors of the Third Chimurenga. They became very active during the past election times where they openly engaged in harassment of those considered to be anti-ZANU-PF. The police and the army either stood by or assisted these irregular forces in the harassment of the civilian population. The army and the police’s connivance at the violence of the state and its direct interference in civil life and politics came out clearly toward the 2002 presidential elections. The military leaders, comprising commanders of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF), Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), Zimbabwe Prison Services, and the Secret Service, led by General Vitalis Zvinavashe, issued a televised message to the people of Zimbabwe to the effect that they would never salute any leader (elected by the people) who had no liberation credentials. The incumbent leader of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, clearly had liberation credentials as a former guerrilla leader of ZANU and ZANLA in the 1970s’s liberation war. However, his opponent and competitor in the run up to the presidential elections, Morgan Tsvangirai of MDC, had no clear liberation war credentials. So the military chiefs were vowing that even if he was going to win presidential elections, they were not going to salute him as the new president of the country. Their statement was a masked coup d’état threat in the event of the MDC winning elections.

Prior to the general elections of 2000, the war veterans continuously threatened the Zimbabwean populace with its ‘song of going back to the bush’ if ZANU-PF lost the elections. This was not a new ZANU-PF election strategy. In the first democratic elections of 1980, ZANU-PF in alliance with its ZANLA military wing already threatened the people that if ZANU-PF lost the elections, they were ‘going back to the bush’ (Stiff 2000).

The Zimbabwe army commander, Constantine Chiwenga (a successor to Vitalis Zvinavashe), directly drummed up support among soldiers for President Robert Mugabe’s re-election in 2002. He toured almost all army barracks urging soldiers to rally behind ZANU-PF to thwart a possible victory by Morgan Tsvangirai, the MDC leader (The Financial Gazette, 31 May 2001).

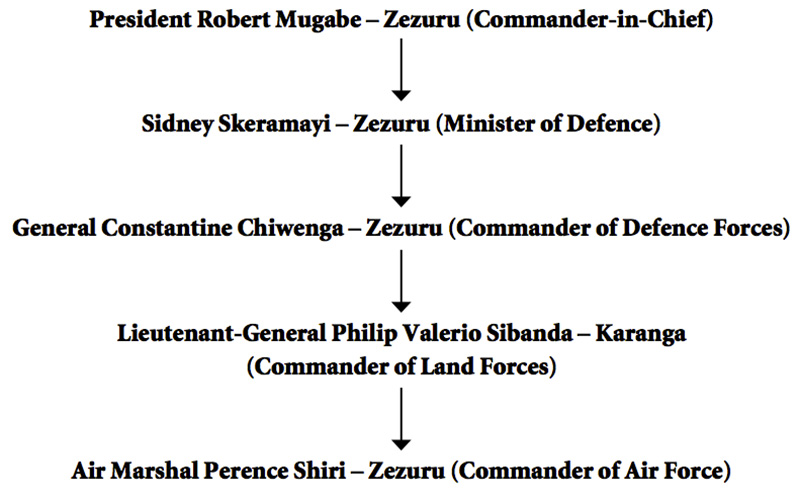

Zimbabwe’s top hierarchy in the defence force is exclusively dominated by Mugabe loyalists that included General Solomon Mujuru, General Vitalis Zvinavashe, Air Marshall Perence Shiri and General Chiwenga. All these men fought as senior members of ZANLA, the military wing of ZANU-PF during the liberation struggle. In other words, these military leaders are just as nationalist in ideological orientation as the civilian leadership of ZANU-PF. They are ‘nationalists in uniforms’ whose loyalty to ZANU-PF as a party is beyond question. The most disturbing issue is that the majority of these men also hail from the Zezuru sub-Shona ethnic group where President Robert Mugabe comes from. This amplifies a worse form of ethnicisation of the military which is even more dangerous than politicisation.

The above scenario at the top level of the military forces explains the solidity of the nationalist-military alliance. The question that needs to be answered is: What devices have been used by the ZANU-PF civilian regime to strike such a solid and enduring deal with the military forces?

Techniques of Creating a Nationalist-Military Oligarchy in Zimbabwe

Several devices have been utilised to create the nationalist-military oligarchy in Zimbabwe.

- Ethnic Factor – This technique has been used widely in post-colonial Africa where the post-colonial state is a conglomeration of different ethnic groups with doubtful loyalty to the ruling elite. The Zimbabwean army is today dominated by the Shona ethnic group. The top leadership is derived from President Mugabe’s Zezuru ethnic group. This creates an enduring loyalty to the party and its leadership derived not only from ethnic affiliation but also from ‘home-boyism’. Despite the fact that General Philip Sibanda, an ex-ZIPRA combatant and a Karanga, has been appointed the head of the ZNA, he is surrounded by not only Shona but Zezuru loyalists of Mugabe. The issue of the dominance of the Zezuru ethnic group in the top posts in the military emerged together with the debate on succession and the so-called Tsholotsho Declaration, leading Chris Maroleng of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) to write of ‘Zimbabwe’s Zezuru Sum Game’ (Maroleng 2005b). The argument is that President Robert Mugabe is Zezuru and the first Army General Solomon Mujuru is also Zezuru and Mugabe has appointed the wife of Gen. Mujuru as his first Vice-President ahead of Emmerson Mnangagwa (a Karanga) who was seen by others as the logical successor to Mugabe based on his loyalty and impressive liberation war credentials as well as post-independence political career. What Chris Maroleng terms the ‘Zezuru Sum Game’ is simply interpreted as a move by Mugabe and his Zezuru associates to establish a fiefdom through gaining total political dominance in key institutions including the army, thus elbowing the Karanga faction from power. As it stands today, the seniority structure in the army is evident in Figure 8 on page 76.

- Instrumental Pay-Offs – The ruling party has succeeded in ‘buying’ the loyalty of the military through selective material payments and privileges. The top leadership of the army is well accommodated, given good cars and they benefited from the land reform programme ahead of the landless peasants.

- Political Co-optation – Senior members of the military work together with the civilian members of the government. Some retire into being members of parliament, governors and party-political functionaries. Those who participated in the liberation struggle are considered to be the ears and eyes of ZANU-PF wherever they are. All war veterans have been turned into party functionaries. The ZANU-PF government has increasingly used the military in civilian activities. The widely criticised Operation Murambatsvina was conducted by the military. Military and security personnel have been placed in several top-level positions in civilian institutions. At the helm of the Electoral Supervisory Commission (ESC), the Grain Marketing Board (GMB) and the National Oil Company of Zimbabwe (NOCZIM) are military people. This has made the military to perceive themselves as more than the custodians of Zimbabwean territorial integrity and sovereignty from external threats. They see themselves as some Praetorian Guard that must safeguard ZANU-PF’s political dominance (Maroleng 2005:5). Some analysts even argue that ZANU-PF and Robert Mugabe’s heavy reliance on the military means that this is the only institution they can trust at the moment (Chitiyo & Rupiya 2005).

- Ideological Indoctrination – The Zimbabwean armed forces are deliberately indoctrinated with the values of ZANU-PF as a party. All the high ranking members of the military forces are expected to be members of ZANU-PF. As it stands today, the military is led by those who passed through the nationalist liberation war and who are thoroughly indoctrinated with ZANU-PF nationalist ideology. National Service Militias are another group of indoctrinated people who are now being recruited into joining the army and police.

Figure 8: Senior Military Personnel in Zimbabwe

Conclusion

The Zimbabwean military see themselves, first and foremost, as the servants of ZANU-PF and the particular ZANU-PF constructed regime, rather than servants of the state and the people. Political detachment and neutralism were rendered meaningless by political manipulation and were replaced by an ethos in which enthusiasm for the existing ZANU-PF regime becomes an essential quality in a military officer. This is vindicated by the enthusiasm displayed by both the police and army officers in harassing workers and civilian population during strikes, and other civil events deemed anti-ZANU-PF. Army units, particularly in Harare, kept track of those who were assumed to have voted for the MDC in the 2000 and 2002 elections and subjected them to various forms of harassment and beatings in the post-election period. Up to the time of writing, Zimbabweans stay in fear of their military forces.

Zimbabwe is reeling under a re-radicalised nationalist project presided over by ZANU-PF with the support of the military forces. The Zimbabwean state is militarised in form and content. There is a solid alliance between the war veterans and the ruling party, between the Youth Militias and the ruling party, and between the ZNA and ZRP and the ruling party. The commissioner of the police, Augustine Chihuri, openly stated that he was a ZANU-PF member (The Daily News, 5 September 2001).

The post-nationalist alternative represented by the MDC and the various civic groups such as the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) has been beaten back by this solid nationalist-military alliance in Zimbabwe. This has so far enabled the old forces of the nationalist liberation struggle to temporarily dislocate and displace the pro-democracy elements in the country.

Sources

- Alexander, J., McGregor, J. & Ranger, T. 2000. Violence and Memory: One Hundred Years in the Dark Forests of Matebeleland. London: James Currey.

- Baynham, S. 1992. Civil-Military Relations in Post-Independent Africa, in South African Defence Review, No. 3 (1992).

- Bhebe, N. & Ranger, T. (eds.) 1995. Soldiers in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- British Military Advisory and Training Team 1982. BMATT/1406, 3 September 1982. A confidential document.

- Campbell, H. 2003. Reclaiming Zimbabwe: The Exhaustion of the Patriarchal Model of Liberation. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Catholic Commission for Justice & Peace, and Legal Resources Foundation 1997. Breaking the Silence: Building True Peace: A Report on the Disturbances in Matebeleland and the Midlands Region, 1980-1988. Harare: CCJP & LRF.

- Chitiyo, K. & Rupiya, M. 2005. Tracking Zimbabwe’s Political History: The Zimbabwe Defence Force from 1980-2005, in M. Rupiya (ed.), Evolutions and Revolutions: A Contemporary History of Militaries in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

- Finer, S.E. 1962. The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics. London: Pall Mall.

- First, R. 1972. The Barrel of a Gun. Harmondsworth: The Penguin Press.

- Government of Zimbabwe 1997. National Defence Policy, Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe. Harare: Government Printers.

- Huntington, S.P. 1957. The Soldier and the State. New York: Random House.

- Kriger, N. 1992. Zimbabwe’s Guerrilla War: Peasant Voices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriger, N. 2003. Guerrilla Veterans in Post-War Zimbabwe: Symbolic and Violent Politics, 1980-1987. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lan, D. 1985. Guns and Rain: Guerrillas and Spirit Mediums in Zimbabwe. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- MacLaughlin, J. 1996. On the Frontline: Catholic Missions in Zimbabwe’s Liberation War. Harare: Baobab Books.

- Maroleng, C. 2005a. Zimbabwe: Increased Securitisation of the State?, in Institute for Security Studies Situation Report, 7 September 2005.

- Maroleng, C. 2005b. Zimbabwe’s Zezuru Sum Game: The Basis for the Security Dilemma in Which the Political Elite Finds Itself, in African Security Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2005.

- Martin, D. & Johnson, P. 1981. The Struggle for Zimbabwe: Chimurenga War. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House.

- Mazarire, G.C. & Rupiah, M. 2000. Two Wrongs Don’t Make A Right, in Journal of Peace, Conflict and Military Studies, Vol. 1 No. 1, 2000.

- Morris-Jones, W.H. 1980. From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe: Behind and Beyond Lancaster House. London: Frank Cass.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2003. The Post-Colonial State and Matebeleland: Regional Perceptions of Civil-Military Relations, 1980-2002, in Williams, R., Cawthra, G. & Abrahams, D. (eds.), Ourselves to Know: Civil-Military Relations and Defence Transformation in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2005. Fatherhood and Nationhood: Joshua Nkomo and the Re-imagination of the Zimbabwe Nation in the 21st Century. Unpublished paper, Monash University, South Africa, 2005.

- Nhongo-Simbanegavi, J. 2000. For Better or Worse? Women and ZANLA in Zimbabwe’s Liberation Struggle. Harare: Weaver Press.

- Nordlinger, E.A. 1977. Soldiers in Politics: Military Coups and Governments. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Ranger, T. 1985. Peasant Consciousness and Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe. London: James Currey.

- Ranger, T. 2003. Nationalism, Democracy & Human Rights in Zimbabwe. Volume Two. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Sithole, M. 1999. Zimbabwe: Struggles Within the Struggle. Harare: Rujeko Publishers.

- Solidarity Peace Trust 2003. National Youth Service Training: Shaping Youth in A Truly Zimbabwean Manner: An Overview of Youth Militia Training and Activities in Zimbabwe. Report, 5 September 2003.

- Stiff, P. 2000. Cry Zimbabwe: Independence: Twenty Years On. Alberon: Galago.

- Tshabangu, O. 1979. The March 11 Movement in ZAPU – Revolution Within the Revolution for Zimbabwe. Heslington: Tiger Papers.

Newspapers

- The Chronicle, 11 November 1981. The Herald, 7 November 1980. The Herald, 21 August 1980.

- The Herald, 4 July 1982.

- The Herald, 28 January 2002.

- The Financial Gazette, 31 May 2001.

Oral Interviews

- Jervious Moyo, Gwanda, Zimbabwe, 19 January 2005. Leonard Ndlovu, Gwanda, Zimbabwe, 19 January 2005.

Other Sources

- Tsvangirai 2005. Letter by Morgan Tsvangirai to President Robert Mugabe, 28th December 2005.

- Parliamentary Debates 1980. First Session: First Parliament, 19 August – 19 September 1980.

- Constitution of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 1980.

Notes

- The MDC suffered an internal split in 2005 over the issue of participation in the senatorial elections. Tsvangirai was opposed to participation but some of his colleagues wanted participation. At the time of writing Tsvangirai is the president of one faction and the other faction is led by Professor Arthur Mutambara.

- This incident, just like the whole story of the contribution of ZAPU to the liberation struggle, remains less well known. However, it is documented in a booklet by O. Tshabangu (1979).

- Having lost their political influence, most former RSF senior officers soon lost interest in the military. In June, Lt. Gen. Peter Walls tendered his resignation to the Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, citing personal reasons. Senior Air Force Commander Alexander McIntyre also resigned and was followed by other middle- and lower-ranking white soldiers.

- Arms cashes were found in ZAPU-owned properties like NITRAM and Egg’s Nest around Bulawayo. Another arms cache was found near Wha Wha prison in Gweru. Up to its dissolution in 1987, ZAPU denied having any connections with the arms caches. Some argue that the arms were hidden by the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) who wanted to implicate ZAPU in internal disturbances of the 1980s. That ZANU wanted a casus belli to destroy ZAPU was very apparent as they continually tried to associate Joshua Nkomo with the dissidents. In Zimbabwe under ZANU-PF, political opponents are commonly associated either with the intention to stage a coup, violently destabilise the country or assassinate Robert Mugabe. First, it was Joshua Nkomo and ZAPU, next it was Bishop Muzorewa, third it was Ndabaningi Sithole and now it is Morgan Tsvangirai and the MDC. At the time of writing this paper, ZANU-PF government is talking about having found arms caches in Manicaland and they are frantically trying to link MDC to these weapons. Many people think it is the work of the CIO.

- In 2002, I participated in a research project sponsored by the Institute for Security Studies (SA) and the Centre for Defence Studies (Zimbabwe) on civil-military relations and defence transformation in Southern Africa. I did field work in Matebeleland region focusing on Ndebele perceptions of the military. There was overwhelming evidence that the Fifth Brigade that killed an estimated 20 000 civilians was Shona speaking. In some instances people mentioned that the Fifth Brigade itself told people that it was a Shona army sent to wipe out the Ndebele for what they did in Mashonaland in the 19th Century. See Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2003.

- After the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987, many ex-ZIPRA combatants who were unfairly dismissed from ZNA during the early 1980s tried to re-join the army indicating that they did not leave on their own volition. A certain Mr. Gibbs Sibanda (not his real name) who now runs a bottle store and is a member of the Zimbabwe War Veterans Association and an ex-ZIPRA, told me that he was a Captain in the then Army and was based in Battle Fields near Kwe Kwe in 1982. He narrated how he left the army. He said one day he was approached by two ex-ZANLA colleagues who asked him whether he still wanted to remain alive. His answer was ‘yes’. He was then told that the position of Captain he was holding was only for ex-ZANLA forces, not ZIPRA. He was told to relinquish the post and to apply for demobilisation. Two of his colleagues who refused to demobilise just disappeared up to today.

- The self-proclaimed leader of the farm invasions, Joseph Chinotimba, shot his neighbour in Glen Narah, Harare, accusing the woman of being a supporter of the MDC. He was never prosecuted.