Abstract

This article offers a brief review of repression and conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) over the last century, before analysing the transition process and the country’s prospects for consolidating a democracy in the future. The DRC peacekeeping process has been the United Nation’s most expensive project to date with an annual budget of over USD 1 billion per annum. The July elections were largely peacefully conducted and reflected a high level of participation. Building a stable sustainable democracy, however, will be difficult. The DRC must survive its poverty, lack of structure, debt, low levels of investment, internal fragmentation, and a history of violence and predatory neighbours. It must rapidly develop a strong, just state able to effectively broadcast power; resolve boundary issues in the face of potential internal and external threats; develop a common sense of nationhood and identity amongst its citizens along with a culture of constitutionalism (rule of law); acquire and effectively use aid from the international community; deal with potentially predatory neighbours; achieve rapid economic development and install effective dispute resolution mechanisms across a broad front to minimise a drift back to violence. It’s a daunting agenda with limited resources.

1. Introduction

On 30 July 2006, 25 million newly registered voters in the DRC had the opportunity to go to the polls to elect a new government. In the context of forty years of repression and a very violent civil war a peaceful election was a victory in itself. Elections however are no guarantee of a sustainable democracy; they only open the door to its possibility. Previous democratic elections in the Congo in 1960 and 1965 provided but a brief brutal interlude between the Belgian and Mobutu regimes. This article offers a brief record of repression and conflict in the DRC over the last century, before analysing the transition process and the country’s prospects for consolidating a democracy into the future.

The DRC encompasses over 2,3 million square km, an area two thirds the size of Western Europe. Despite a rich endowment of mineral deposits and huge potentials for hydro-electric power it is shockingly underdeveloped, boasting only about 500km of tarred roads. The vast majority of its population of 55 million people live in poverty with an estimated average per capita income of only USD 110 per annum (USD 770 ppp).1 Its Human Development Index ranking of 36,5 reflects not only poverty, but poor life expectancy (44,7 years) and literacy levels (65%).

2. Conflict Transformation and Democratisation

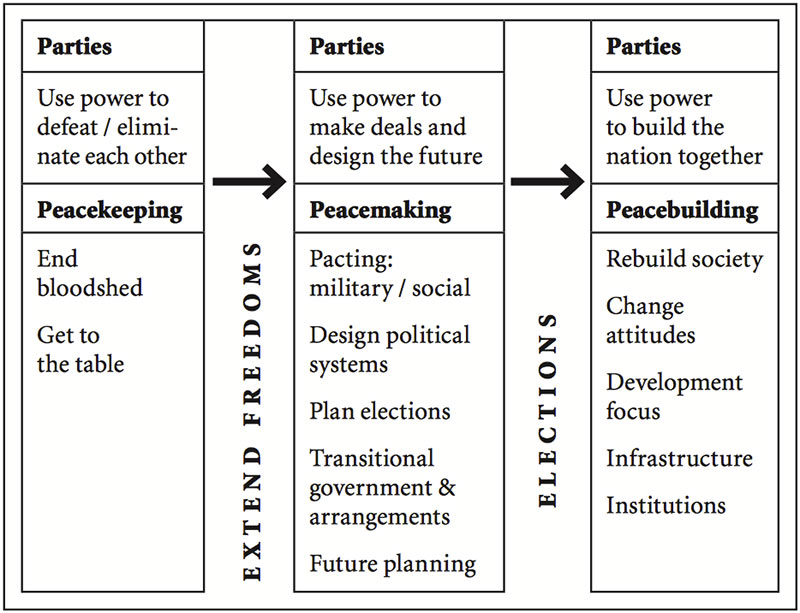

Transitions to democracy in contexts such as the DRC are a conflict transformation project. Typically the process of transforming a society of violent conflict in which parties use their power to eliminate or subjugate one another into one of tolerance in which they invest their joint energies into state-building moves through several distinct phases. In conflict transformation language, there is shift from peace-keeping to separate warring parties and bring them to the negotiation table, to peace-making in which leaders or representatives of parties negotiate a deal or a peace agreement, and then to peace-building in which conflict-generating environmental conditions are changed, and attitudes between the parties modified to allow an agenda of mutual interest to emerge and be developed. Such a process is synonymous with the now well-documented phases of a transition from authoritarian rule and violence to democracy (see Figure 1 page 38), through a process of liberalisation in which there are increased political and civil society freedoms, a period of pacting in which parties suspend their use of power against one another to stabilise the change process, elections and then democratic consolidation (Anstey 2006:281-321, De Villiers 1993, Ethier et al 1990, O’Donnell et al 1986). Progress depends on the design and implementation of effective conflict management systems in each phase of the process, but more especially the willingness of parties to respond to each other’s fears, hopes and dilemmas. Conflict resolution structures and procedures are of limited value in the absence of a shift in mindset on the part of those who use them. They become effective because parties are intent not simply on defeating one another, but because they want solutions which are just and which are responsive to the needs, hopes and fears of others – in short of everyone involved! In Zartman’s (2001:7-16) terms, conflict transformation requires shifts in perceptions of stakes amongst parties (from a zero to a positive sum game), a change in attitudes (from conflictual to accommodative) and the use of tactics to promote non-violent forms of exchange.

Figure 1: Democratisation: A Transformation of Conflict Project

Democracy is a values system. While democratic societies are often measured by the shape of their constitutions, judicial systems, commissions, forums, laws, structures and civil societal freedoms, the social glue which holds them together in diverse societies is a mix of inclusion, tolerance, accommodation (Goodin 1995) and a shared preference for non-violent settlement of disputes. Cultural influences shape the mode of exchange, but however direct or deferent the character of their debates – they have debates! Democracies reflect non-violent competition for power, and universal rights to vote and run for office, to assemble, to move freely, to form political parties, trade unions and other civic organisations, to voice opinions, to a free press (alternative sources of information), to protection from the courts, and to freedoms from fear and want (Anstey 2006:281-284, Diamond et al 1989, Dahl 1982). However deep the differences between groups, they are dealt with through debate, negotiation, the courts and other forms of non-violent dispute resolution. In Rousseau’s terms, a viable social contract (democracy) requires all individuals to submit to conditions they would impose on others – all are (and feel) equal under laws founded in the general will and regulated through impartial judicial systems. Individuals and groups see greater benefit from accommodating one another’s interests than in going to war over them.

As conflicts escalate, interest in accommodation diminishes. They escalate owing to poorly managed negotiations and/or as a consequence of strategies in which a party deliberately provokes open conflict because it sees greater utility in a fight (at least for a period) than in compromise or problem solving. Whatever the reason, the consequences are similar – parties polarise (in positions and perceptions); as they build in-group solidarity to fight effectively, they demonise each other; communications diminish; information is selectively (mis)understood; ‘hawks’ replace ‘doves’ as group leaders, and ‘if you are not with us, you are against us’ sentiments prevail. As parties use increasingly coercive tactics to achieve their ends, the process becomes self-sustaining. Anger, desires for revenge and for inflicting pain on the other overwhelm motives for peace. Original issues may be forgotten as each responds to the tactics of the other. Parties become afraid to suspend arms lest they are momentarily lulled and defeated by force. Advocacy for ‘anticipatory defence’ and rights to ‘pre-emptive strikes’ see offensive action argued away as self-preservation. Parties become increasingly entrapped in provocation-attack cycles. In addition, some groups find the conflict process itself gratifying – the adrenalin of the struggle, the camaraderie, the seduction of a ‘grand cause’ coupled with the demonisation of opposing groups facilitate a capacity to dismiss casualties on the other side as ‘unfortunate collateral damage’ (Anstey 2006:36-52, Pruitt & Rubin 1986, Coser 1956). The DRC has been through a brutal period of escalated conflict which some stakeholders realistically fear will contaminate a future democracy.2

In scarce-resource societies, capacity for mutual accommodation is often stretched. Where there has been war anger, desires for revenge and redress must somehow find expression in a manner which does not lead parties back to armed conflict. People do not just suddenly become tolerant. The pull to democracy is often hampered by the baggage of recent conflicts, and in contexts where people have been brutalised into a desperate struggle for survival. There is not an absence of conflict in democratic societies. Rather they deal with conflict in a different way. They identify sources of conflict within their own reality. They design systems to manage such conflicts in ways that minimise the risks of violence between citizens, and protect them from abuses by the state. In all societies, but especially those with a high risk of conflict, it is important then to have accessible trusted systems of conflict management. These should extend to all potential flashpoints and areas in the country. They should operate under the ambit of a constitution and their activities should consciously serve the interests of national unity and strengthening democratic values.

3. A Century of Violent Conflict and Repression in the DRC

Henry Morton Stanley acquired control over trade routes into Africa along the Congo River for King Leopold II of Belgium by enticing over 400 illiterate local chiefs to make their marks on treaties transferring land ownership to a trust. This ‘personal colony’ was formalised during the 1885 Berlin Conference where the continent was carved up amongst Europe’s powers. Desirous of an empire but anxious not to provoke the giants of imperialism, an ambitious Leopold played a duplicitous game, securing the region for himself under a banner of humanitarian endeavour while permitting a ruthless repression of the indigenous people. Over two decades he amassed a fortune in ivory, and then rubber, through a system of terror and forced labour, with the loss of an estimated 10 million lives (Hochschild 2006:233). After the iniquities of his system were exposed, Leopold ceded his ‘Congo Free State’ to the Belgian state in 1908, a year before his death. It became the Belgian Congo (Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006a:2).

The Belgian government continued to conscript huge numbers of indigenous people into forced porterage, military, rubber and mining endeavours. Indeed, during the Second World War forced labour of 120 days a year was legally permitted (Hochschild 2006:279). Meredith (2005:96) reports that the colony ‘was controlled by a small management group in Brussels representing an alliance between the government, the Catholic Church and the giant mining and business corporations, whose activities were virtually exempt from outside scrutiny’. Nevertheless, the country was run with increasing success through heavy investment in industrial development – the industrial production index rose from 118 to 350 between 1948 and 1958, with productivity almost tripling over the period. Immense mineral riches in Katanga boosted the local economy (and that of Belgium). There was also greater humanitarian investment. Missionaries established a dense network of schools and clinics across the country, and mining companies provided housing and welfare schemes (Meredith 2005:97). By 1960 the Congo boasted 560 beds per 100 000 inhabitants and the highest literacy rate in Africa (42%). However, there was little development of indigenous people beyond primary education. At the time of independence there were no Congolese doctors, school teachers or officers in the military (Meredith 2005:97, Johnson 1996:514), and only between six (Van de Walle 2001:129) and thirty (Meredith 2005) black college graduates in the country. The Belgians withdrew messily from the Congo in the colonial exodus of the continent in 1960 – and then continued to play a part in the chaos which followed.

The Congo’s first democratic election in 1960 saw 120 ethnically based political parties engage in a (sometimes violent) contest for power. The National Congolese Movement achieved most votes (33 of 137) and against the wishes of the Belgians and its firebrand leader, Patrice Lumumba was elected Prime Minister. Joseph Kasavubu became the President in the nation’s first national elections (Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006a:2). Following Lumumba’s open criticism of colonialism, black soldiers in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) mutinied, ejected their white commanders and embarked on a violent attack on Europeans and Africans from other persuasions. After five days, the Belgians sent in troops to restore order, an act denounced by United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld as a threat to peace and order in the region. Moise Tshombe, elected Premier of Katanga Province in the mineral-rich south, declared independence on 11 July 1960. The UN assembled a force to oblige a re-unification (Johnson 1996:515). This ugly mix of violent exchanges between local politicians, the military and a half-extracted Belgian colonialism was compounded by Cold War politics. To protect their mineral investments, the Belgians intervened, backing Tshombe’s secession. They were actively supported by the United States of America (US), interested in establishing a pro-western, anti-communist government in the Congo. Lumumba was seen as a risk and the US funded a programme launched to displace him (Nugent 2004:86-87, Blum 2003:156). On 14 July 1960, following international criticism, a UN force replaced the Belgian forces. The UN force entered but did nothing to reverse the secession of Katanga. Compounding the problem, Albert Kalonji declared independence for the South Kasai region (Nugent 2004:86). After the UN and the US refused him military assistance to put down the Katanga uprising, Lumumba asked for and received Soviet assistance but failed to achieve a military victory.

Encouraged by the US and the UN, President Kasavubu then dismissed Lumumba despite his support in the Congolese Parliament, and closed down the radio station he wished to use to broadcast his case to the nation. Lumumba responded by trying to dismiss Kasavubu but was left in a bad position, lacking military power, and lacking popular backing in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) while the UN was backing his opponent. On 14 July Mobutu conducted a military coup and placed himself in charge of the country. He tracked down and detained Lumumba and then handed him to Tshombe on 17 January 1961 – he was assassinated the same day with direct Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Belgian involvement (Meredith 2005:112, Nugent 2004:87, Blum 2003:158-159).

The Congo became a cauldron of competing internal and external forces, with the US reportedly supporting both rebels and the government at one point. By 1963, the US and the UN had decided that a unified Congo was a better bet and exerted influence to bring Tshombe’s secession to an end as well as end a resistance from Gizenga (Lumumba’s deputy) backed by Soviet assistance (Blum 2003:159). In 1964, widespread rebellion broke out across the eastern Congo with Lumumba supporters setting up a ‘Peoples’ Republic of the Congo’ in Stanleyville and executing an estimated 20 000 ‘counter-revolutionaries’. They were assisted by forces from Algeria, China, Egypt and Cuba. The US along with mercenaries from South Africa and Rhodesia assisted Tshombe with a mission to bring order to the region. About 2 000 white expatriates found themselves trapped by the war in Stanleyville. The rebel leader Gbenye sought unsuccessfully to bargain a cessation of American bombing raids with the safe release of 300 Belgian and US hostages it had taken. On 24 November 1964, US and Belgian paratroopers staged a rescue mission. In the ensuing battle, about 2 000 white expatriates were safely evacuated from eastern Congo but 300 were killed by rebels. The war between Tshombe’s forces and the rebels was short but brutal – about a million died in the carnage (Meredith 2005:115).

In April 1965, Tshombe’s party won 122 of the 167 seats in the National Assembly. A tension arose between Kasavubu and Tshombe over the appointment of a prime minister, with the latter eventually assuming office. Things continued to fall apart and Tshombe did not last long. In November 1965, Che Guevara withdrew his small Cuban expeditionary force which had been assisting Laurent Kabila’s rebels in the east of the country, disillusioned with their indiscipline, corruption, incompetence and dissolute character (Meredith 2005:149-150).

In the same month, Mobutu, with US support, launched the ‘Second Republic’ (November 1965 – April 1990), overthrowing Tshombe and Kasavubu to settle into thirty-five years of oppressive rule punctuated by periodic single-party elections. The country was renamed Zaire. Single-party rule (by Mobutu’s party the MPR)3 rapidly gave way to single-person rule (Nugent 2004). An oppressive stability was interrupted briefly in 1977 by raids into the Katanga Province by Angola-based rebels (FNLC)4 who were defeated with the assistance of French and Moroccan troops with US logistical support. During the 1980’s, the country was plundered by Mobutu who is estimated to have salted away up to USD 5 billion in European bank accounts – more than the national debt (Nugent 2004:236-237)! The national infra-structure collapsed, the administration and army disintegrated with disrupted supplies, fuel and pay. Independent opposition groups emerged.

When the Cold War ended in 1989, Mobutu’s support from the West, which had assisted to hold him in office, ended.

In the context of rising instability Mobutu initiated a process of ‘popular consultation’ around the future of the country and re-introduced a multi-party system of government in 1991. In the face of delays and subterfuge, opposition groups and civil society convened a Sovereign National Conference (CNS) doggedly holding to its work in the face of disruptive tactics by government. Mobutu was to be permitted to remain as Head of State but the CNS elected Etienne Tshisekedi (now leader of the UDPS5 party which boycotted the 2006 elections) as Prime Minister under a transitional constitution. The plan was scuppered by Mobutu, however. Political negotiations finally saw a single institutional framework in September 1993 and the Constitutional Act of Transition passed in April 1994. Presidential and legislative elections were, however, never held. Genocide and civil war in Rwanda spilled over into eastern Congo (the Kivu provinces) with interahamwe (Hutu militia) using Hutu refugee camps as bases to conduct hostilities in Rwanda against the Tutsi. In October 1996, Rwandan forces invaded Zaire, supporting an internal armed coalition force led by Laurent Kabila (AFDL).6 While Nugent (2004) notes that official accounts suggest that Rwandan forces limited their hostilities to militia, French (2004) and Guest (2004:119) argue it was an invasion of massive violence in which Rwandan forces decimated not just Hutu militia but also fleeing refugees. A South African peace initiative led by Mandela foundered, largely because Mobutu perceived a victory in hand (Laurence 2006:6).

On 17 May 1997, Kabila drove Mobutu from the country,7 proclaimed himself President, annulled the Transition Act and banned political opposition to give himself sole control. His decision in July 1998 to order out Rwandan and Ugandan troops that helped him to office sparked a civil war. The withdrawing forces assisted in the creation of a rebel group (RCD)8 which sought to take over Kinshasa (Apuuli 2004). This mission was thwarted by troop support from Angola, Chad, Sudan, Zimbabwe and Namibia, which enabled Kabila to retain control over Kinshasa and much of the west of the country, despite loss of authority over the east and south. Kabila’s belief that he could retain power sank South Africa’s second mediation effort in 1998 (Laurence 2006:6). The RCD then split into two major factions – RCD-Goma and RCD-Kinshasa – after internal differences. In February 1999, Uganda assisted the formation of the rebel group MLC9 built around ex-Mobutu soldiers, which took control of the northern part of the country. The spread of internal and external actors and level of violence made for a complex negotiation process.

4. Pacting: From Peacekeeping to Peacemaking

The first major victory for peace is often through peacekeeping efforts intended to keep warring parties apart and end the bloodshed. Wider returns are realised if an intervention creates space for negotiations, not simply in relation to substantive issues (designing elections, drafting constitutions) but also for relationship-building purposes. Leaders are given the opportunity to discover one another at a level beyond armed confrontation, with the potential for new levels of mutual understanding, insight and trust. Within the space of a ceasefire, parties are obliged to search for solutions in a manner which responds to each other’s interests and fears, and start behaving as political parties rather than armies. Such interim phases then serve as a transition into ‘normalised’ political exchange.

Analysts of democratic transitions refer to this phase of the change process as one of pacting, in which key stakeholders suspend their capacity to do damage to one another and start redirecting their energies towards designing and implementing systems of mutual accommodation. Recognising that political change is inevitable, or that their interests might be best preserved through negotiation rather than violent insurrection or repression, they enter pacts at political, military, social and economic levels in which they suspend their capacity for coercion in order to stabilise relations through the democratisation process.

At a political level, such pacts see the formation of transitional governments operating under interim constitutions with the task of designing and delivering a final democratic arrangement. In this way, a bridge is built from violence, oppression and fragmentation to an inclusive democratic society. Such pacts, of course, should occur not only on a political but also on social, economic and military levels. Many African democracy initiatives have foundered owing to their concentration simply on political exchange, and their neglect of civil society foundations (Bratton & Van de Walle 1997:9). One of the keys to the success of the South African transition to democracy was the role played by civil society – business, trade unions and the churches – in facilitating the change process (Anstey 2004:57-58).

The pacting phase gives all parties involved a window into the future. The shape of a constitution and the effectiveness of interim bodies of government and reconciliation signal to voters what they might expect after elections. It gives them something a little more than promises to vote for, and to hold their elected representatives to account to later on.

Participation in multi-party negotiations is closely bound up in processes of conflict de-escalation. However, they are delicately balanced. Parties arrive in a context of violent exchange with sharply defined in-group-out-group boundaries. During the process, if they wish to make progress on their own issues, they must look for ways to accommodate those of others. They must learn to deal with issues ‘on their merits’ if they are to avoid a reversion to violence. They must use the negotiation process as a means of protecting and furthering their interests. In this exercise they become aware not only of each other’s fears, hopes and aspirations, but also of each other’s goals, agendas, alliances and leverage. Parties may begin to look for new alliances, to see greater benefit in boycotting talks than participating in them, and to see returns in conditioning their participation – all of which may threaten the process. However, such shifts, trade-offs and manipulative endeavours should perhaps be seen as normative in a change process. The intention of negotiations is for parties to change, not to come out as they entered.

The signing of the Lusaka Cease-fire Agreement on 10 July 1999 by the governments of the DRC, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Namibia, and Zimbabwe and a little later by the MLC and factions of the now divided RCD was a breakthrough. It opened the door to the deployment of the UN Organisation Mission in the DRC (MONUC) to support the cease-fire in November 1999. MONUC’s mandate had four phases: forcible implementation of the cease-fire agreement; monitoring and reporting violations; disarmament, demobilisation, repatriation, resettlement, reintegration; facilitating the transition to credible elections (www.monuc.org 24/7/06). With a budget of over USD 1 billion per annum, it is the UN’s largest peacekeeping mission ever. Progress was, however, only really achieved after Laurent Kabila’s assassination by a bodyguard in January 2001. His son, Joseph, assumed power and immediately opened the door to a democratic transition. The Lusaka Agreement committed parties to work out a power-sharing arrangement for the formation of a transitional government and to form an integrated national army drawn from all forces and factions. Former Botswana President, Ketumile Masire facilitated the first meeting of the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) (including the government, RCD-Goma, MLC, non-armed opposition and civil society) at South Africa’s Sun City between 25 February and 19 April 2002.

While participation in multi-party talks enables new forums of exchange, and facilitates new understanding and ways of managing differences, not everyone comes to the table for the same reasons, or with the same visions of outcome. Parties change their positions, demands and tactics during the process in the context of new possibilities. Some may participate because they believe strongly in the democratic process – a principled participation. Others engage because they perceive the costs of sustained violence as too high with the risk of loss or stalemate and mutual destruction. Such groups may slow the process and seek deals beyond their actual backing on the ground. Then there are those who believe that they will win elections. For this group, talks and elections have a higher utility than continued violence. The intentions of likely winners, however, may not be democratic – negotiations and elections may simply offer a less costly and more socially acceptable route to eventual subjugation of political opponents. They will be interested in pressuring a rapid outcome. Some groups may participate simply to stop others achieving certain outcomes and make use of spoiling tactics. There may be some who neither want to continue violent conflict nor achieve a final outcome. Those who doubt both their capacity to win a war or an election may prefer a ‘permanent transition’ in which they have secured seats and influence in an interim national assembly. Such groups may resort to tactics of delay, dispute and ongoing debate. Negotiations in peace-making processes then reflect and must survive multi-motive scenarios. It is the capacity to respond to the motives, fears and concerns of the spread of parties in negotiations which facilitates workable deals, and it can be expected within multi-party negotiations that relations will become strategic with new coalitions and threats of boycotts as parties jockey for power.

Not unexpectedly then, the pacting process in the DRC experienced problems. Mistrust dogged the 2002 Sun City talks. Parties squabbled over the legitimacy of representatives, with rebel leaders contesting each other’s participation and accusing others of being stooges of the Kabila government. Some argued that Kabila should not remain in power while negotiations were in process (MLC, RCD-Goma, UDPS). This was dealt with through Mbeki’s proposal that Kabila’s retention of office be tempered by an arrangement of vice-presidencies amongst opposition groups. Talks were threatened when certain rebel groups (RCD-Goma) continued fighting, a tactic only ended after pressure from the UN Security Council and international community. The Uganda backed MLC then reneged on a pre-negotiation deal it had signed with the RCD-Goma to adopt a common strategy for the talks to announce that it had done a deal with the Kinshasa government (Kabila) to the effect that Kabila would become executive president and its own leader Bemba, prime minister for an interim period of 30 months. In the face of protest from other participants, and the ire of external player Rwanda, the Kabila-Bemba deal did not hold. Under international pressure another round of talks opened to seek an ‘all-inclusive’ agreement in Pretoria in October 2002. This round brought together representatives of the government, MLC, RCD-Goma, RCD-ML,10 RCD-N,11 political opposition, civil society and the Mai-Mai. According to Apuuli (2004), the rebel groups became aware they could not win militarily and were under direct pressure from Uganda and Rwanda (their external backers) to resume talks.

A complicating factor in the cessation of hostilities was the interests and activities of external parties, not least Rwanda and Uganda which had not only sponsored internal rebel groups, but whose troops did direct battle in Kisangani at one point. Suppliers of arms, finance or other key resources have important influence over parties’ capacity and motives to raise conflict levels or participate in peace dialogues (Huntington 1998:291-298). A critically important step in the peacekeeping process, then, was the international pressure brought to bear on external parties to withdraw troops from the DRC. Rwanda agreed to pull out in July 2002 following a commitment from the DRC to apprehend all interahamwe on its soil, and in September 2002 Uganda agreed to withdraw its troops and work with the DRC in a Pacification Committee in Ituri (on the DRC-Uganda border) where ethnic tensions bubbled between Hemas and Lendu (Apuuli 2004). The internal rebel groups they supported however remain, albeit in political party mode for purposes of the election. The choices of these groups post-election will be critical to the state-building project which lies ahead.

Although the major parties agreed to a formula for power sharing at the political, economic and military levels over a two-year transition period in the Pretoria Agreement on 17 December 2002, ethnic fighting in the Ituri region, and some late protests by RCD-Goma delayed final signature at Sun City to 1 April 2003. Kabila was to remain Head of State of an interim government and commander-in-chief of the army, assisted by four Vice-Presidents, one from each of RCD-Goma, MLC, the Kabila government and non-armed opposition. A formula for the distribution of Ministers’ and Vice-Ministers’ posts was agreed, as well as seats for parties within a 500-member Transitional National Assembly and a 120-member Senate (see Table 1 on page 50). In addition, the agreement included the integration of various RCD and Mai-Mai forces into a national army. An Independent Electoral Commission (CEI) was established, as were a National Human Rights Observation, a High Authority for the Media, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a Commission for the Fight against Corruption. By this time, an estimated 3,5 million people had lost their lives in direct conflict or as a consequence of collapsed social and health systems in the DRC war, and another 5 million had been displaced.

Table 1: Quota of Seats Agreed for the Interim Government

President & Commander-in Chief of Army: Joseph Kabila |

|||||

| Party | Vice-Presidents | Ministers | Vice-Ministers | National Assembly | Senate |

| Ex-government | 1 | 7 | 4 | 94 | 22 |

| Non-armed opposition | 1 | 7 | 4 | 94 | 22 |

| Civil society | – | 2 | 3 | 94 | 22 |

| RCD-Goma | 1 | 7 | 4 | 94 | 22 |

| MLC | 1 | 7 | 4 | 94 | 22 |

| RCD-N | – | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| RCD-ML | – | 2 | 2 | 15 | 4 |

| Mai-Mai | – | 2 | 2 | 10 | 4 |

The interim constitution increased the number of provinces in the Congo from 11 to 25, more accurately reflecting the DRC’s ethnic diversity. Additionally, it was agreed that each province should be run on a semi-autonomous basis retaining 60% of wealth generated for local projects, serving perhaps to ease longstanding secessionist tendencies in the mineral-rich south. Provision was made for elections every five years. The final outcome of elections may well see strong shifts in the distribution of positions of influence and seats in the legislature. Here the choices of losers and winners of the 2006 election will be critical (discussed later in this paper).

The risks for power-holders in oppressive systems include not only a loss of political power, but also of controls over the military and police, and of systems of patronage and corruption. They may be subject to acts of retribution for past acts of oppression. Without offers of protection in a future dispensation, they may see little reason to relinquish power peacefully. So it is here where the issues of war crimes tribunals, truth and reconciliation processes, and amnesties may come onto the table. In such moments of handover, previous victims of atrocities wield a new power and control over the process. Further casualties may only be avoided by assuring power-holders that they will receive protections they did not accord others during an oppressive regime. If these uncertainties are not dealt with, the risks of a military coup or scuppering of elections may be heightened. The past poisons the future because it is not dead – it lives in people in the form of residual anger, unresolved pain, expectations of redress, mourning and a sense of betrayal. Those who want most desperately to ‘move on’ are often those who suffered least under a previous regime or stand to gain most in a new one. For those who were victims, there is often unfinished business which the designers and players in a new dispensation must respond to if they hope to give long-term life to the infant democracy. Many may experience little change in their lives – they may remain locked in a survival crisis with few opportunities and little access to decision making. These groups need special access to systems of justice, conflict resolution and reconciliation. Parties at war do terrible damage to one another, and often to anyone in the vicinity of their hostilities. The DRC has experienced terrible loss of life over the last decade. Death, rape, violent assault, and fear have stalked its citizens. The prospect of a democracy offers hope for a future free of such atrocities and fears but it does not in itself deal with the pain of past experiences. It was, therefore, a worrisome signal that some parties argued on the eve of elections that little had been done to integrate armies or deal with issues of reconciliation.

5. Elections

The administration of the DRC election was a massive project involving 269 parties, 33 presidential candidates and about 9 700 parliamentary candidates across 25 provinces. The system which permitted votes for individuals within party lists made for complex ballot papers. In Kinshasa voters were faced with a six-page A3 ballot form reflecting hundreds of candidates. Electoral banners and posters reflected not only the names and in some cases pictures of candidates, but also their numbers on lists and the pages on which their names could be found (for example, number 840 on page 5). The election was coordinated through 11 provincial centres, 64 liaison offices and over 50 000 voting stations. The DRC’s election reflects the largest ever UN investment in such a project with annual expenditure estimated at about USD 1 billion. Over 15 500 peacekeeping troops were deployed in the country for several years, with 520 UN military observers, 324 civilian police and 2 493 civilian staff supporting the process. Poor road systems and weak communication infrastructure gave rise to a process of huge complexity. Over 200 000 electoral staff and 45 000 police were involved. Some early problems were experienced with payment systems and consequent strike action. Despite these headaches, the CEI registered an estimated 90% of the voting population – a quite extraordinary feat! About 65% voted in a referendum over the constitution in December 2005 with 80% approving it. Despite some equipment problems and a slow validation process, the exercise was regarded as a success (Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006b:36-37).

Elections can be situations of high conflict. On the eve of the election the International Crisis Group (ICG) (2006) identified a range of possible problems. Delays in the process had created a perception of a reluctance to cede power on the part of some interim parliamentarians. There were rising levels of unrest in Kinshasa, Mbuji-Mayi, Lubumbashi, Katanga, and Kivu areas. Concerns were being expressed over problems in election security, weak policing, potential interference by militia, politicised armed forces and accusations that the government in power was using its power to marginalise opposition elements, control key points, and manipulate the media. Further the ICG recorded fears of fraudulent electoral activities, disparities in wealth and access to funding amongst parties, corruption amongst officials and concerns over the boycott of the process by the UDPS. In addition, monitoring of the elections was seen as under-resourced with security risks making some areas potentially no-go zones (Katanga). There were fears that the judiciary, responsible for dispute resolution, was highly politicised (in favour of Kabila). MONUC proposed a ‘committee of the wise’ comprising five eminent Central African officials as a team to resolve disputes between candidates over misuse of government funds; misconduct by electoral or government officials; discrimination based on ethnicity or religion; abuse of the parties’ code of conduct; and other complaints. The fragility of the process was reflected in several breakdowns: RCD soldiers mutinied in Bukavu in May 2004, Kanyabayonga in November 2004 and Rutshuru in January 2006. Mai-Mai in the Kivu and Katanga areas clashed with the newly integrated National army (FADRC)12 in 2005. In a problem-solving workshop for election stakeholders organised by EISA and the Carter Center a week before elections, delegates raised concerns about the complexity of the ballot paper for a society with a high degree of illiteracy; lack of voter readiness; the implications of non-participants (UDPS); the problem of ‘losers’; tensions between the CEI and political parties and amongst parties themselves; and police bias in the process. A few expressed pessimism that the elections might be a disaster as not enough was in place to proceed.

Despite these fears the voting process on 30 July 2006 was largely peaceful. Only about 150 of the 50 000 voting stations were destroyed or attacked. Barring some violence in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi, voters conducted themselves well. Indeed, they were queuing to vote well before 06h00 in many stations across the country. A 70% turnout was recorded – 17,9 million people of the 25,4 million registered voted.

Parties in the DRC, however, have shown themselves more able to run elections than to live with their results. The first round of the Presidential election did not produce a clear majority winner. Groups loyal to Kabila (who won about 45% of the vote) and Bemba (about 20%) attacked each other in Kinshasa leaving thirty two dead before a cease-fire was achieved following international intervention. International efforts with President Mbeki in the forefront are seeking to ensure a peaceful run-off election between Kabila and Bemba on 29 October 2006.

It is hard to imagine a more fragmented legislature than that delivered once votes had been counted at the end of September 2006. In all, 68 parties and 63 independents won seats to the new legislature (Appendix A). Kabila’s PPRD13 as the winner of the largest number of votes took only 111 of the 500 seats (22,2%). Bemba’s MLC came in second with 64 seats (12,8%). No other party achieved above a 10% representation in parliament. Indeed, 29 parties won only a single seat, 12 won two seats, 7 achieved 3 seats, and 6 got 4 seats – 54 parties with less than a 1% representation! Government, then, must be by coalitions and alliances amongst parties – democratic but difficult to pull together, even in cases of a few minority parties seeking alliances on issues, let alone the plethora of players which must now assume responsibility for taking the DRC into the future. Unless some extraordinary long-term coalitions now emerge, the legislature may well prove ineffectual, offering plenty of room for a future of Presidential domination and a return to ‘big-man’ politics, albeit off a democratic base.

6. Democratic Consolidation: State building in the DRC

Democratic transitions in Africa have largely been short-lived. If the DRC’s fledgling democracy is to fly, it must survive its poverty, lack of infra-structure, debt, low levels of investment, internal fragmentation, a history of violence and intrusive neighbours. A sustainable peace will require inter alia rapid development of a strong and just state; a resolution of boundary issues along with a common sense of nationhood amongst citizens; a culture of constitutionalism (rule of law); focused ongoing assistance from the international community, including controls over predatory neighbours; and effectively designed systems of state including credible, accessible systems of dispute resolution wherever there is potential for conflict in the future (Anstey 2004; Fukuyama 2004; Herbst 2000).

A strong state is able to design and effectively implement policies and laws (broadcast power). This implies a competent legislature and law enforcement system, but also efficient revenue collection to cover the costs of such a system. European states were defined by the extent to which they were able to effectively extend power beyond a core to peripheral areas (Herbst 2000). ‘Failed states’ on the other hand are unable to protect their citizens from violence, guarantee rights at a domestic or international level, or maintain viable democratic institutions (Chomsky 2006:38,110). The art of democratic state building is the capacity to design and implement laws and policies in a manner regarded as legitimate by its citizens. Fukuyama (2004:2) states that ‘the task of modern politics has been to tame the power of the state, to direct its activities towards ends regarded as legitimate by the people it serves, and to regularise the exercise of power under a rule of law’. A capacity to coerce and extract revenues must then be supplemented by a capacity to protect and serve citizens. Impoverished African states are often unable to deliver these objectives to any beyond a small core area within their larger territory. This enables the formation of resistance groups in peripheral areas who mobilise on the platform of state incapacity. External support may boost their power to render areas ungovernable. Mobilising resistance in such scenarios is a great deal easier than the role of governance. Toppling a regime is no guarantee for a new group in power that it will be able to extend power any more effectively than its predecessor in scarce-resource economies. So a key challenge for the new government of the DRC is how to develop means of effectively broadcasting power across a massive geographical area despite an extraordinarily weak infra-structure, and in a context in which externally supported rebel groups have thrived.

This problem changes shape rather than diminishes in the context of a democratically elected state. Problems of broadcasting power and service delivery will in many senses be as large for a democratic state as an authoritarian one – whatever its character, it faces a large delivery/small capacity crisis. If rebel groups ignore the democratic credentials of a new government, a costly military may continue to absorb revenues. Expectations of development spending, social delivery, and state protection will however be higher for a democratic government than for a military one. Fukuyama (2004:7-57) suggests a distinction between the scope of a state’s activities and its strength or capacity. While an economist may see the optimal state as that of the US, strong with a limited scope of functions (such as defence, law and order, protection of property rights, macroeconomic management, public health), Europeans have argued that strong states must also attend to issues of social justice through more expansive functions in areas such as education, environment, social insurance, financial regulation, industrial policy and wealth redistribution. African states for the most part face a crisis of capacity in a context of huge social need. The weakness of the private sector and civil society push for a more expansive scope of state functions. In previous decades, bloated, ineffectual civil services contributed to problems in many African economies, but the structural adjustment programmes introduced to reduce state spending often created other problems. Power elites increased spending on the military and other departments enabling a consolidation of control while reducing social need expenditure. Analysts now argue that smaller states should not imply weaker states (Fukuyama 2004:7-57, 161-164, Van de Walle 2001:235-286, Bratton & Van de Walle 1999). There can be little contest with proposals for state capacity building, but there have to be questions about those aimed at reducing the scope of state functions to mirror those of some advanced economies where there are other sources of social and economic energy. Fukuyama (2004:12) implies that states with limited resources weaken themselves further when they are ‘unable to provide basic public goods like law and order or public infrastructure’ while trying to run parastatals and expansive wealth redistribution programmes. This is of course true, but the pressure for social delivery in poor nations cannot be ignored or postponed. Democracies are about votes, and votes may depend on service delivery. One may be tempted to shake out neo-patrimonial systems which served purposes of extended control and stability in favour of more efficient systems of social delivery, but not at the expense of social delivery. If the state is not to assume a direct role, it must rapidly develop policies which will enable other societal stakeholders to do so – a clear auxiliary role.

African nations have largely accepted the national boundaries imposed by European powers in 1885. As Herbst (2000) points out, however, the absence of territorial conflicts in Africa after 1960 served for a period to obscure the internal instability of its nations. The DRC faces several territorial problems. Firstly, secessionist movements in the mineral-rich south have a long history. Secondly, the DRC has over a long period of time been subjected to invasion and looting by other nations which have also supported internal rebel groups, aggravating problems of internal control and unity. In short, the integrity of the DRC may be under internal and external threat into the future.

States are defined not simply by their formal boundaries but by the sense of identity shared by their citizens. The design of a democratic DRC suggests an effort to respond to its ethnic diversity (through an increased number of provinces) and mute secessionism (through retention of provincial revenues). However, the question remains unresolved as to whether it is a unified state with an overriding sense of national identity amongst its people or simply an assemblage of geographically defined ethnic groupings each covetous of its identity and resistant to control by others. The absence of a strong national identity will inhibit a broad-based consensus for state-building purposes and, coupled with poor infrastructure, limits the capacity of a central government to acquire revenues, offer services, and broadcast control effectively. A semi-literate electorate with limited access to media and limited mobility is more likely to have voted for candidates on the basis of their local status and ‘known-ness’ (grassroots affiliation), than on the basis of policy formulations for the Congo as a whole (national policy preferences). So it is unlikely that the new National Assembly will take office with a clear development policy for the nation – it will have to be worked out. A national consensus in the DRC may prove difficult owing to its fragmented character, but also because of the challenges of delivering to massive need out of a scarce-resource economy.

Just as territory issues cannot be understood simply in terms of formal boundaries, so the exercise of formal authority cannot rely simply on the ballot box and a modern constitution. A nation requires a shared sense of identity, and a democracy requires a culture of constitutionalism. Modern Africa has had no shortage of constitutions, but what it has lacked is a capacity and shared will to implement these (Bratton & Van de Walle 1999; Johnson 1996:517). Many of the fears expressed by parties in the lead up to elections – the choices of losers, impartiality of the military, the police and the judiciary – reflect a lack of trust in the commitment of others to a rule of law. This is as much about the choices of winners as of losers of elections.

Those who failed to win levels of influence they aspired to, those fearing loss of wealth, opportunity or control over systems of patronage or embedded corruption and those who may be exposed to criminal charges under a new dispensation may see themselves as ‘losers’ in the election. In weak economies, election to political office is often the golden key to economic opportunity – loss of political status has very high stakes indeed. The risk of electoral losers taking the ‘Savimbi’ option of a return to arms, either immediately or once peacekeepers and the international media have withdrawn, may require maintenance of a ‘peacekeeping readiness’ by the international community for some time into the future. Zartman (1985:13) has pointed to the problems created by ‘leftover liberation movements’ which simply continue fighting if they do not win power.

The behavioural commitments and perceived integrity of likely ‘winners’ are of course just as important. Van Zyl Slabbert (1992) in the lead up to South Africa’s democratic moment in 1994 pointed out two important criteria for a successful transition – contingent consent, in which potential losers continue to play the electoral game in the belief that future opportunities to compete will not be denied by the winners, and bounded uncertainty in that all groups believe that whoever wins the election will sustain human rights and civil liberties for all into the future. Those who believe they might lose an election continue to play the democracy game because they trust that the ‘winners’ will play according to certain rules; that they will not be prevented from running for election again into the future; that they will have the freedom to organise for such a purpose; that they will not be subject to arbitrary or repressive action by the winners; and that economic opportunities will be open to them in a new dispensation. Democracy requires of ‘losers’ that they accept the outcome of elections, and it requires of ‘winners’ that they do not abuse their authority – both must play within the constitutional framework. This is a much underestimated leap in mindset for scarce-resource societies with deeply entrenched systems of patronage. It requires that agendas of broad-based social and economic delivery, based on effective administrations with competent work-forces, prevail over traditions of clan-based employment and tender practices.

Equally, those who decided to boycott the elections, such as the UDPS, must make choices of constitutionalism in the aftermath of elections. A party which decides not to participate may do so for many reasons, but it cannot hold the democracy train back – if it does not board, it will be left at the station. Having made the democratic decision not to participate is not a license to call the process unfair. Nor, however, is it a ‘forever decision’. Viable democracies are about frequent and fair elections. So a party can participate in future elections, advise its supporters to vote for other parties with similar policy positions or even not to vote at all – but it cannot legitimately advise them to undermine the electoral process for those who have decided to play, or resort to violence.

One way to view a democracy is that it is in essence a series of temporary or transitional governments. In addition, parliaments should perhaps be seen less as platforms for control than forums for national problem solving. Where elections are a regular feature of political life, parties can be voted in or out depending on their delivery to the voting population. Voters can choose to vote others into office if they are dissatisfied with delivery – in this sense loss may be but a temporary state of affairs. This is what keeps everyone honest in the system – loss of an election should not translate into loss of economic opportunity or access to justice or the right to organise for the next election.

Thinking about police services and armed forces must also be transformed. Within a unitary constitutional state, a judicial system seeks to protect people from infringing each other’s rights as well as from abuses by the state. Police are not an instrument of control for any particular political party or grouping of parties, but a vehicle to protect the constitutional rights of all citizens in a nation. In emerging democracies this often demands a shift in mindset for politicians, the wider society and amongst members of the police and armed services themselves. This has been a difficult project in the South African transformation process. In the case of Zimbabwe, the ruling party has subverted its judiciary and its police services, turning them into instruments of ZANU-PF14 policy and interests.

Effective, credible, accessible conflict management systems are key to effective transitions on many fronts. Party liaison forums, independent mediation and arbitration mechanisms, peace structures, independent forums for controls over and accreditation of police and army activities all have relevance during a transition period and into elections. After elections, those in government face the challenge of building and consolidating the new democracy. However successful the transition process to the point of elections, it is just the beginning. Infant democracies are fragile and vulnerable to attacks and to crises of expectation. The culture of violence which develops in war-torn nations makes it important for political and civil society stakeholders to assess the issues they will face in a new regime and design means of responding to these (Harris & Reilly 1998:135-342). Amongst others, conflict management systems must be designed to respond to tests of rights enshrined in a new constitution (courts; human rights commissions); tensions over delivery of social services (local ombuds; land commissions; aid and refugee bodies); the arguments of secessionist movements (mediation and courts); tensions over war crimes and atrocities (amnesty/truth and reconciliation/war crimes choices); unification of police and armed forces (carefully managed transformation projects) and complaints over their conduct (independent complaints directorates; courts); and conflicts arising from corporate practices, sometimes in interaction with government (auditor-general; pension ombuds; public protector offices).

The DRC has never realised its own wealth. First the Belgians plundered its resources, then Mobutu and in more recent times its neighbours Uganda and Rwanda. Not surprisingly, there is suspicion of those indicating a desire to help! There is not sufficient space for this debate here, but a coherent plan for sustainable economic development will be a critical platform for a viable democracy. Key to this will be a quick resolution of Fukuyama’s (2004) debate around state capacity and scope. The DRC must develop economic policies which will attract investors, promote economic growth, offer a fair deal to labour and satisfy voters. If the state is not to assume a less expansive role within the economy then it must develop policies for economic growth and redistribution with private sector interests. Although subject to criticism from all its social partners at various stages, South Africa’s National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC) offers a good example of a forum for social dialogue through which government can continuously engage with business, labour and civil society interests for development purposes. The consolidation of a democracy depends on an awareness that democracy is not simply a set of political arrangements, but one whose survival is dependent on civil society. A failure to develop democracy beyond political systems has collapsed many of Africa’s democratic initiatives experiments (Anstey 2004; Bratton & Van de Walle 1999). The strength of democracy, then, depends on building and empowering civil society rather than simply centralising controls. As Sandbrook (1993:121-150) points out, however, recognising the importance of a strong civil society for democracy is one thing; building one in the African context is another, fraught with obstacles.

7. Conclusion

After a bumpy start, the DRC’s democracy project progressed through a successful political pacting process and, with massive external investment, a peaceful election process with a high level of participation. At best, however, the DRC has only a fledgling democracy – and a sickly one. If it is to become ‘flight-worthy’, an extraordinary array of problems must be overcome and some important tests passed. The new democratic government must make important decisions as to state building to find an optimum balance in the mix of capacity and delivery demands – a problem magnified in the context of the nation’s poverty and weak infra-structure which weaken capacity to broadcast power effectively. A major test must be passed regarding internal and external threats to national integrity. Predatory neighbours must be kept in check and internal forces must see greater value in working within the democratic state than in breaking from it. The extent to which a ‘culture of constitutionalism’ exists amongst electoral ‘losers’ and ‘winners’, and the military and the police in the immediate aftermath of elections will be tested – and it is a test that must be passed if a meaningful democracy is to emerge from the ashes. The violent response of loyalists to Kabila and Bemba which greeted the announcement of a second round for presidential elections in October 2006 was symptomatic of how delicately poised the democratic experiment remains. Recognising the ongoing high potential for conflict in the DRC makes it imperative that popularly accredited, effective, accessible systems of conflict management be designed and resourced across society to prevent, minimise and regulate tensions into the future. Ways have to be found to support mechanisms which prevent a drift back to violence – peace must be seen by major stakeholders to have greater utility than a reversion to war. A democracy is not simply a matter of institutions, but a matter of societal will. Institutions will not prevail if the intent is not to use them or to corrupt them. For this reason, the final motivation perhaps needs to be for sustained external assistance to give this democratic project a chance – responsiveness to refugees, to those who are starving and traumatised by war, to the need for focused development programmes, to human rights education, to the development of infra-structure – these will be what holds this democracy together. Even should systemic corruption be defeated, a huge investment of resources will be needed to make this happen.

In this context, despite the size of investment in the democratic project to date and its successful election process, development of a sustainable democracy in the DRC will remain an immensely difficult project into the future. This, however, does not mean it is a project which should be abandoned if there are problems in early attempts at flight. In Lincoln’s words ‘the probability that we may fail in the struggle ought not to deter us from the support of a cause we believe to be just’.

Postscript

At the time of going to print the Independent Electoral Commission had announced that Kabila had won the second round of the Presidential election with 58% of votes against Bemba’s 42%. After a period of tension in which there were fears of violence in Kinshasa, Bemba indicated that he would challenge the result through the Supreme Court. The choice of the legal route was a positive one. When the Court upheld the result, Bemba made a further positive choice in stating he would respect the decision and seek leadership of the opposition. There is much to do, but if Bemba delivers to these commitments and Kabila affords them a dignified response, it will go a long way towards stabilising the DRC’s new democracy and laying the foundations for a culture of constitutionalism to develop.

Sources

- Anstey, M. 2004. African Renaissance – Implications for Labour Relations. South African Journal of Labour Relations, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 34-82.

- Anstey, M. 2006. Managing Change, Negotiating Conflict. Cape Town: Juta.

- Apuuli, K.P. 2004. The Politics of Conflict Resolution in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: The Inter-Congolese Dialogue Process. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, Vol. 4, No. 1.

- Blum, W. 2003. Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War 2. Cape Town: Zed Books.

- Bratton, M. & Van de Walle, N. 1997. Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chomsky, N. 2006. Failed States. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen Unwin.

- Coser, L. 1956. The Functions of Social Conflict. New York: Free Press.

- Dahl, R.A. 1982. Dilemmas of Pluralist Democracy – Autonomy vs Control. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- De Villiers, D. 1993. Transition by Transaction: A Theoretical and Comparative Analysis of Negotiated Transitions With Special Reference to South Africa, 1989-1992. Unpublished D Phil Thesis, University of Port Elizabeth.

- Diamond, L., Litz, J.J., & Lipset, S.M. (eds) 1989. Democracy in Developing Countries. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2002. Democracy, Elections and Conflict Management: Handbook. Johannesburg: EISA.

- Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006a. EISA Observer Mission Report D.R. Congo. EISA Observer Mission Report No. 21. Johannesburg: EISA.

- Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006b. Election Update No. 2, DRC. Johannesburg: EISA.

- Ethier, D. (ed) 1990. Democratic Transition and Consolidation in Southern Europe, Latin America and South East Asia. London: Macmillan Press.

- French, H.W. 2005. A Continent for the Taking: The Tragedy and Hope of Africa. New York: Vintage Books.

- Fukuyama, F. 2004. State Building: Governance and World Order in the Twenty First Century. London: Profile Books.

- Goodin, R.E. 1995. Politics, in Goodin R.E. & Pettit, P. A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. London: Basil Blackwell.

- Guest, R. 2004. The Shackled Continent. London: Macmillan.

- Harris, P. & Reilly B. 1998. Democracy and Deep-Rooted Conflict. Stockholm: IDEA.

- Herbst, J. 2000. States and Power in Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hochschild, A. 2006. King Leopold’s Ghost. London: Pan Macmillan.

- Huntington, S.P. 1998. The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of the World Order. London: Touchstone Books.

- International Crisis Group. 2006. Congo’s Elections: Making or Breaking the Peace. Africa Report 108, 27 April.

- Johnson, P. 1996. Modern Times: A History of the World from the 1920’s to the 1990’s. London: Phoenix Giant.

- Laurence, P. 2006. SA Mediators Mat Take Fall For New War in DRC. The Sunday Independent, 20 August, p. 6.

- Meredith, M. 2005. The State of Africa. London: Free Press.

- Nugent, P. 2004. Africa Since Independence. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- O’Donnell, G., Schmitter, P. & Whitehead, L. 1986. Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Comparative Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Pruitt, D.G. & Rubin, J.Z. 1986. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate and Settlement. New York: Random House.

- Sandbrook, R. 1993. The Politics of Africa’s Economic Recovery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van de Walle, N. 2001. African Economies and the Politics of Permanent Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Zyl Slabbert, F. 1992. Unpublished address to IMSSA Conference, Natal.

- Zartman, I.W. 2001. Preventive Negotiation: Avoiding Conflict Escalation. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Zartman, I.W. 1985. Ripe for Resolution: Conflict and Intervention in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Notes

- In Purchasing Power Parity (ppp), per capita Gross Domestic Product (pcGDP) is adjusted for cost of living differences by replacing normal exchange rates with a rate designed to equalise the prices of a standard ‘basket of goods and services’. The US rate is taken as the index at 100 (Economist 2006).

- Debate amongst electoral officials, party leaders, electoral observers and mediators in the EISA/Carter Center workshop on 20 and 21 July 2006.

- Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution

- Front National pour la Libération du Congo

- Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social.

- Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaire.

- Mobutu died in Rabat, Morocco, on 7 September, 1997, from prostate cancer.

- Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie.

- Mouvement pour la Libération du Congo.

- Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie-Mouvement de Libération.

- Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie-National.

- Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo.

- Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie.

- Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front.

Appendix A

Provisional Results

| Registered | 25 420 199 |

| Voters | 17 931 238 |

| Counted votes | 16 937 534 |

| Spoilt ballots | 870 758 |

| Blank ballots | 122 946 |

| Turnout | 70,54% |

Extracted from Electoral Institute of Southern Africa 2006b

Presidential Election

| NO | NAMES OF CANDIDATES | NO OF VOTES | % OF VOTES |

| 1 | Kasonga Banyingela | 82.045 | 0,48 |

| 2 | Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo | 3.392.592 | 20,03 |

| 3 | Alou Bonioma Kalokola | 63.692 | 0,38 |

| 4 | Eugene Diomi Ndongala | 85.897 | 0,51 |

| 5 | Antoine Gizenga | 2.211.290 | 13,06 |

| 6 | Emmanuel-Bernard Kabatu Suila | 86.143 | 0,51 |

| 7 | Joseph Kabila Kabange | 7.590.485 | 44,81 |

| 8 | Gerard Kamanda wa Kamanda | 52.084 | 0,31 |

| 9 | Oscar Kashala Lukumuenda | 585.410 | 3,46 |

| 10 | Norbert Likulia Bolongo | 77.851 | 0,46 |

| 11 | Roger Lumbala | 75.644 | 0,45 |

| 12 | Guy-Patrice Lumumba | 71.699 | 0,42 |

| 13 | Vincent de Paul Lunda Bululu | 237.257 | 1,40 |

| 14 | Pierre-Anatole Matusila | 99.408 | 0,59 |

| 15 | Christophe Mboso Nkodia Pwanga | 78.983 | 0,47 |

| 16 | Antipas Mbusa Nyamwisi | 96.503 | 0,57 |

| 17 | Raphael Mbuyi Kalala | 44.030 | 0,26 |

| 18 | Nzanga Joseph-Francois Mobutu | 808.397 | 4,77 |

| 19 | Florentin Mokonda Bonza | 49.292 | 0,29 |

| 20 | Timothee Moleka Nzuluma | 17.753 | 0,10 |

| 21 | Justine Mpoyo Kasavubu* | 75.065 | 0,44 |

| 22 | Jonas Mukamba Kadiata Nzemba | 39.973 | 0,24 |

| 23 | Paul-Joseph Mukungubila Mutombo | 59.228 | 0,35 |

| 24 | Osee Muyima Ndjoko | 25.198 | 0,15 |

| 25 | Arthur Zahidi Ngoma | 57.277 | 0,34 |

| 26 | Jacob Niemba Souga | 40.188 | 0,24 |

| 27 | Wivine Nlandu Kavidi* | 54.482 | 0,32 |

| 28 | Marie-Therese Nlandu Mpolo Nene* | 35.587 | 0,21 |

| 29 | Catherine Marthe Nzuzi wa Mbombo* | 65.188 | 0,38 |

| 30 | Josepth Olenghankoy Mukundji | 102.186 | 0,60 |

| 31 | Pierre Pay Pay wa Syakassighe | 267.749 | 1,58 |

| 32 | Azarias Ruberwa Manymwa | 287.641 | 1,69 |

| 33 | Hassan Thassinda Uba Thassinda | 23.327 | 0,14 |

* Female candidates

Source: Independent Electoral Commission (CEI), 20 August 2006.

Legislative Election

Number of Elected Members of DRC Parliament

| No | PARTY/ORGANISATIONS/INDEPENDENTS | DENOMINATION | SEATS |

| 1 | Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie | PPRD | 111 |

| 2 | Mouvement de Libération du Congo | MLC | 64 |

| 3 | Parti Lumumbiste Unifié | PALU | 34 |

| 4 | Mouvement Social pour le Renouveau | MSR | 27 |

| 5 | Forces du Renouveau | Forces du Renouveau | 26 |

| 6 | Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie | RCD | 15 |

| 7 | Coalition des Démocrates Congolais | CODECO | 10 |

| 8 | Convention des Démocrates Chrétiens | CDC | 10 |

| 9 | Union des Démocrates Mobutistes | UDEMO | 9 |

| 10 | Camp de la Patrie | CAMP DE LA PATRIE | 8 |

| 11 | Démocratie Chrétienne Fédéraliste-Convention des Fédéralistes pour la Démocratie | DCF-COFEDEC | 8 |

| 12 | Parti Démocrate Chrétien | PDC | 8 |

| 13 | Union des Nationalistes Fédéralistes du Congo | UNAFEC | 7 |

| 14 | Alliance des Démocrates Congolais | ADECO | 4 |

| 15 | Patriotes Résistants Maï-Maï | PRM | 4 |

| 16 | Alliance Congolaise des Démocrates Chrétiens | ACDC | 4 |

| 17 | Union du Peuple pour la République et le Développement Intégral | UPRDI | 4 |

| 18 | Rassemblement des Congolais Démocrates et Nationalistes | RCDN | 4 |

| 19 | Convention des Congolais Unis | CCU | 4 |

| 20 | Parti de l’Alliance Nationale pour l’Unité | PANU | 3 |

| 21 | Parti des Nationalistes pour le Développement Intégral | PANADI | 3 |

| 22 | Convention Démocrate pour le Développement | CDD | 3 |

| 23 | Union Nationale des Démocrates Fédéralistes | UNADEF | 3 |

| 24 | Union des Patriotes Congolais | UPC | 3 |

| 25 | Convention pour la République et la Démocratie | CRD | 3 |

| 26 | Alliance des Bí¢tisseurs du Kongo | ABAKO | 3 |

| 27 | Union pour la Majorité Républicaine | UMR | 2 |

| 28 | Renaissance Plate-forme électorale | RENAISSANCE-PE | 2 |

| 29 | Forces Novatrices pour l’Union et la Solidarité | FONUS | 2 |

| 30 | Rassemblement des Forces Sociales et Fédéralistes | RSF | 2 |

| 31 | Solidarité pour le Développement National | SODENA | 2 |

| 32 | Alliance des Nationalistes Croyants Congolais | ANCC | 2 |

| 33 | Parti Démocrate et Social Chrétien | PDSC | 2 |

| 34 | Parti de la Révolution du Peuple | PRP | 2 |

| 35 | Union Nationale des Démocrates Chrétiens | UNADEC | 2 |

| 36 | Parti Congolais pour la Bonne Gouvernance | PCBG | 2 |

| 37 | Mouvement pour la Démocratie et le Développement | MDD | 2 |

| 38 | Alliance pour le Renouveau du Congo | ARC | 2 |

| 39 | Démocratie Chrétienne | DC | 1 |

| 40 | Convention Nationale pour la République et le Progrès | CNRP | 1 |

| 41 | Mouvement d’Action pour la Résurrection du Congo, Parti du Travail et de la Fraternité | MARC-PTF | 1 |

| 42 | Union des Libéraux Démocrates Chrétiens | ULDC | 1 |

| 43 | Front des Démocrates Congolais | FRODECO | 1 |

| 44 | Mouvement Solidarité pour la Démocratie et le Développement | MSDD | 1 |

| 45 | Union Congolaise pour le Changement | UCC | 1 |

| 46 | Parti National du Peuple | PANAP | 1 |

| 47 | Union des Patriotes Nationalistes Congolais | UPNAC | 1 |

| 48 | Générations Républicaines | GR | 1 |

| 49 | Parti Congolais pour le Bien-être du Peuple | PCB | 1 |

| 50 | Front pour l’Intégration Sociale | FIS | 1 |

| 51 | Front Social des Indépendants Républicains | FSIR | 1 |

| 52 | Union pour la Défense de la République | UDR | 1 |

| 53 | Convention Nationale d’Action Politique | CNAP | 1 |

| 54 | Mouvement Maï-Maï | MMM | 1 |

| 55 | Conscience et Volonté du Peuple | CVP | 1 |

| 56 | Front des Sociaux Démocrates pour le Développement | FSDD | 1 |

| 57 | Mouvement d’Autodéfense pour l’Intégrité et le Maintien de l’Autorité Indép | MAI-MAI MOUVE. | 1 |

| 58 | Organisation Politique des Kasavubistes et Alliés | OPEKA | 1 |

| 59 | Parti de l’Unité Nationale | PUNA | 1 |

| 60 | Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution | MPR | 1 |

| 61 | Rassemblement pour le Développement Economique et Social | RADESO | 1 |

| 62 | Action de Rassemblement pour la Reconstruction et l’Edification Nationales | ARREN | 1 |

| 63 | Rassemblement des Ecologistes Congolais, les Verts | REC-LES VERTS | 1 |

| 64 | Mouvement du Peuple Congolais pour la République | MPCR | 1 |

| 65 | Alliance des Nationalistes Congolais/Plate Forme | ANC/PF | 1 |

| 66 | Rassemblement des Chrétiens pour le Congo | RCPC | 1 |

| 67 | Convention Chrétienne pour la Démocratie | CCD | 1 |

| 68 | Independent Candidates | Independents | 63 |

| TOTAL PARTIES’ SEATS | 437 | ||

| TOTAL INDEPENDENTS’ SEATS | 63 | ||

| TOTAL SEATS NUMBER | 500 | ||