Introduction

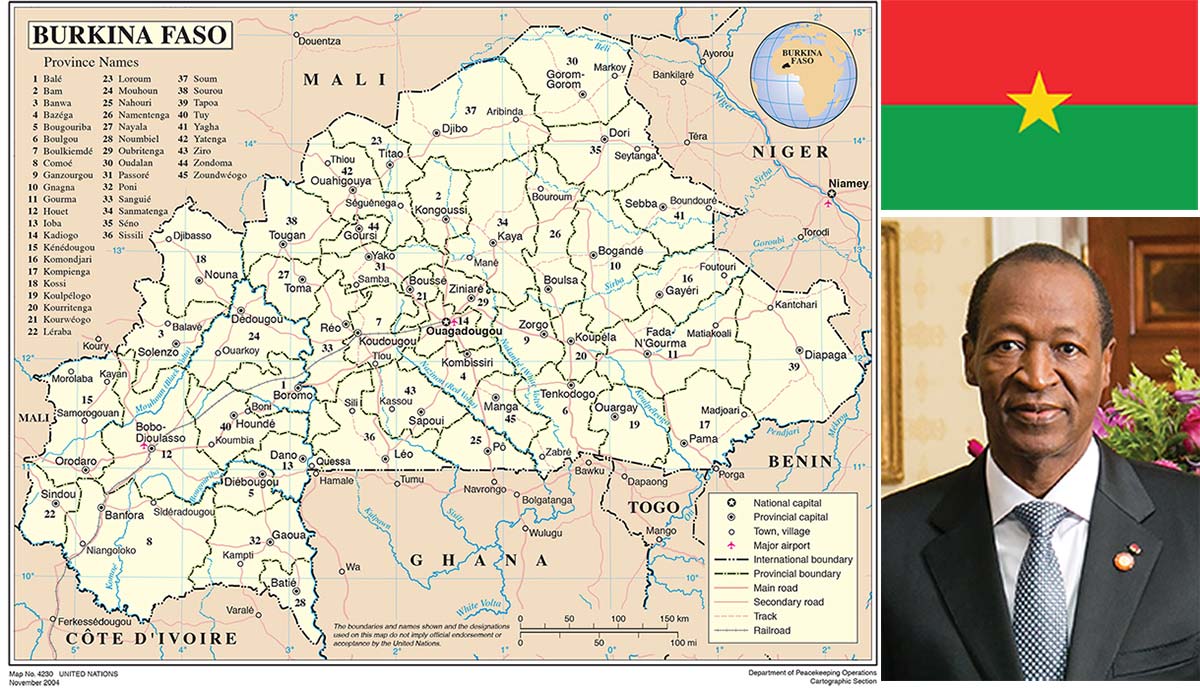

On 30 October 2014, the people of Burkina Faso unanimously took to the streets to protest attempts by their longest-serving president, Blaise Compaoré, to extend his 27-year rule through a constitutional amendment. This development could be likened to the Arab Spring of 2011–2012, where ordinary citizens vehemently rose up in protest against authoritarianism. The recent events have been dubbed Burkina Faso’s “Black African Spring”.1

Following the violent protest, the military announced the dissolution of Parliament and the Cabinet, and the president subsequently resigned. This gave rise to a much-predicted political crisis and an unfortunate military coup. The chief of defence, General Honoré Traoré, had earlier announced his assumption of power, only to be followed by another announcement by Lieutenant Colonel Yacouba Isaac Zida, of the elite presidential guard, as head of state. This indicated splits in the military. Nonetheless, the military managed to pull through the power struggle and confirmed Zida as head of state. This move by the military clearly contradicted Article 43 of the Constitution, which requires the president of the National Assembly to assume power in an acting capacity upon resignation of the national president, and an election should take place within 60 to 90 days. It also violates the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance of the African Union (AU), as well as the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS) Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. This also raises questions of continuing coups in Africa. Certainly, unconstitutional regime change is not a thing of the past. It remains a clear, persistent and present danger.2

Characteristically, Burkinabés, as well as the international community – especially the United Nations (UN), AU and ECOWAS troika – all condemned the military takeover and called for a swift return to civilian transitional administration. The AU, in particular, threatened sanctions against the military regime if it did not hand over power to a civilian-led transitional government by 18 November 2014. ECOWAS, on the other hand, called on the international community not to impose sanctions on Burkina Faso, in view of regional efforts at resolution led by Senegalese president, Macky Sall. However, the key question is whether the current political crisis was unforeseen? Specifically, did the regional and continental early warning systems pick up signals to alert stakeholders to respond proactively and contain the situation? This article, therefore, analyses the current political crises in Burkina Faso by highlighting the precursors and the lack of effective early response to forestall these crises.

Context

For the past three years, there were suspicions that President Compaoré was likely to seek another five-year tenure of office in 2015, despite the constitutional two-term limit. Notwithstanding his alleged history of backing rebels and fuelling civil wars in the region, Compaoré has been instrumental in brokering peace in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, Niger, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. These mediation roles brought enormous political gains to him, his government officials and Burkina Faso in general. He also used his networks to help Western powers in battling Islamist militancy in the Sahel.3

Compaoré came to power through a military coup on 15 October 1987, in which the charismatic and revolutionary military ruler, Captain Thomas Sankara, and 13 other officers were killed under very contentious circumstances. He eventually returned the country to constitutional rule in 1991. Since then, Compaoré has contentiously won all presidential elections – held in 1998, 2005 and 2010. It is argued that since coming to power, Compaoré has put in place a semi-authoritarian regime that combined democratisation with repression, to ensure political stability. Despite the semblance of a free and open political system, the regime was based on three key institutions: the military; a political party, the Congrès pour la démocratie et le progrès (CDP); and traditional chiefdoms. With this architecture, Compaoré maintained tight control over politics and society. He governed in the absence of a formidable opposition and gave civil society enough space through a subtle game of alliances, compromises and illusions.4

The 1991 Constitution has seen five amendments – in 1997, 2000, 2002, 2009 and 2012. The 1997 revision removed the presidential term limit. The two-year limit was, however, reintroduced in 2000 and term duration was reduced from seven to five years. Specifically, Article 37 of the Constitution stipulates that “the president of Burkina Faso is elected for five years by direct universal suffrage in a secret ballot. He can only be re-elected once.”5 Therefore, in August 2005, Compaoré’s announcement of his intention to contest the next presidential election was challenged by opposition parties as unconstitutional. The opposition’s claim was disputed by Compaoré’s supporters, on the grounds that the amendment could not take a retrospective effect. Interestingly, in October 2005, the constitutional council ruled that because Compaoré was a sitting president in 2000, the amendment would not apply until the end of his second term in office.6 This development allowed him to contest the 2005 presidential election and he was re-elected in 2010.

In June 2014, the ruling party called on the president to organise a referendum that would allow him to change the Constitution to seek re-election in 2015.7 The proposed constitutional amendment led to a major rift in the ruling party, culminating in the resignation of about 70 prominent members of the National Political Bureau in early 2014. Among the reasons given for the resignation was their marginalisation and the excessive militarisation of party structures. These individuals moved on to create a new party, the Mouvement du people pour le progrès (MPP). This development significantly changed the balance of political power in the country, with a likely significant impact on the 2015 presidential election.8

It can be argued that there were few alternatives for true democratic succession.9 The CDP has been virtually a single party in what is supposed to be a multiparty system. The president has been the axis around which the whole political and governance structure revolved. The opposition is much divided, with at least 74 political parties. These parties are faced with weak organisational and financial capacities. None of the key figures in the ruling party have emerged as a credible successor. The lack of strong opposition arguably made it less difficult for Compaoré to win four presidential elections, each time with more than 80% of votes.

As was widely anticipated, a proposal for term extension was introduced to the National Assembly, and a debate was scheduled on 30 October 2014 to amend the Constitution to allow Compaoré to seek re-election in November 2015. However, protesters stormed the National Assembly in Ouagadougou, setting it ablaze and looting offices. At least one death was reported.10 Compaoré immediately declared a state of emergency and offered to work with the opposition to resolve the crisis and head a transitional government until elections. However, later in the day, Traoré announced the president’s resignation and that the military would install a transitional government “in consultation with all parties”, and that the National Assembly was dissolved.11

Some have rightly argued that the military hijacked the peoples’ revolution and thus the persistent calls for a civilian-led transitional administration. For instance, following clashes between protesters and security forces, the military said it would install a transitional government within a year. This came after soldiers fired shots at the state television station and barricaded the capital’s main square as thousands of people demonstrated against the military takeover.

Simmering Tensions

Before the events of October 2014, the country was a ticking time bomb, as frustrations and anger had been growing over the years. There had been signals that society was on the edge of political and social crises, although it was kept under tight control. In spite of the country’s turbulent political history – as evidenced in four coups: 1980, 1982, 1983 and 1987 – a period of relative political stability was witnessed under Compaoré’s rule. As he departed from the pro-Marxist revolutionary paradigm of Sankara and embraced a neo-liberal orthodoxy, Burkina Faso enjoyed a relatively high economic growth. Between 2000 and 2006, its gross domestic product (GDP) increased by 6%, and reached 10% in 2012.12 The country also attracted a generous US$13 billion in international development assistance.13However, Burkina Faso ranked only 181 out of 187 countries on the UN’s 2014 Human Development Index, making it one of the world’s poorest countries.14 About 46% of the population live below the poverty line.15 The landlocked nation is heavily dependent on international aid. In particular, the death of one of its major financial partners, Muammar Gaddafi, during the Libyan uprising in 2011 was a blow to Compaoré’s regime. Repeated promises of change were not fulfilled and public distrust grew.16

The frustrations and disquiet were largely manifested in mass protests and labour unrests. For example, earlier in December 1998, the murder of the investigative journalist Norbert Zongo sparked major demonstrations. Zongo was investigating the killing of the driver of Francois Compaoré, the younger brother and special adviser of the former president.17 This was followed by violent protests and strikes throughout the country in 2011. Students protested following the death of one of their colleagues, Justin Zongo, in police custody. There were also protests by trade unions, professionals and rank-and-file soldiers over the high cost of living, and low and unpaid wages. But these did not constitute a mass movement, as opposition parties were not able to build a political platform to offer an alternative to the people’s discontent. Yet, these upheavals lasted several months in the first half of 2011. In particular, on 14 April 2011, there was a mutiny by presidential bodyguards over unpaid allowances, during which the president fled to his hometown of Ziniaire.18 The authority of Compaoré was arguably shaken by the mutiny, as it rested on the army and especially the presidential guards. In response to this 2011 mutiny, the president embarked on a reform of the military, and subsequently assumed responsibility for the reform by becoming defence minister on 20 April 2011. He also reshuffled the government and appointed Luc Adolphe Tiao as prime minister. Successful municipal and legislative elections were held in December 2012. This arguably brought about stronger representation for the political opposition, though the CDP still won a sweeping majority.

The opposition gathered thousands of people against the proposed constitutional amendment between January and May 2014. This signalled that a new dynamic was at work in Burkina Faso. Demonstrations were organised on 18 January 2014 in the capital and other regions of the country. This was followed by the first MPP congress in April 2014, and a large rally held on 31 May 2014 at a stadium, the Stade du 4 Aoí»t in Ouagadougou. Civil society groups also participated in these demonstrations.19

Could the Political Crisis have been Prevented?

While Compaoré remained silent on his political future, many predicted that any attempt to amend the Constitution for a fifth-term bid could provoke a popular uprising. Some also believed that even if Compaoré abided by the Constitution and left power in 2015, his succession might still prove challenging as he had dominated the political scene for decades, placed severe restrictions on political space and concentrated power in a few party cliques and family associates.

Since July 2013, the country had been experiencing sociopolitical tensions over plans to establish a Senate as part of the June 2012 constitutional amendments. This institution was envisioned in the 1991 Constitution, but was never created.20 While the 2012 constitutional revision did not specify the number of senators, the details were passed in an organic law in May 2013. The body was to be composed of 89 members, from a mix of elected representatives at municipal and regional levels, traditional and religious authorities, and others directly appointed by the president.21 The opposition suspected that this might be used to revise Article 37 of the Constitution and organise a constitutional referendum for the same purpose. With 70 of the 127 seats in the National Assembly, the CDP did not have the two-thirds majority required to amend the Constitution. This probably explained the creation of the Senate, which would create the possibility of a parliamentary majority to amend the Constitution without holding a referendum. Others also feared the Senate could be used as a way to ensure that François Compaoré succeeded Blaise Compaoré. François had already been taking an increasingly public role in politics as a member of parliament for the ruling CDP, and some predicted that if he were made president of the Senate, he would be well-placed to take over the presidency.22 One of the opposition leaders, Zéphirin Diabré, organised a demonstration on 28 July 2013 to oppose the establishment of the Senate and the revision of Article 37. The Compaoré regime should have taken a cue from these agitations. Nonetheless, without heeding to these agitations, Senate elections were held in July–August 2013, amid boycott by the opposition. The ruling party won 36 out of 39 of the elected seats, but after mass protests, its installation was postponed.

Questions around the constitutional amendment undeniably presented a threat to political stability and social cohesion. Moreover, the presence of a political army, with a chequered record in the country’s turbulent political past and the growing desire for change among the population, were all factors that pointed to a period of uncertainty ahead for the country. Indeed, there were some developments that were aimed at dealing with the looming political crisis. For example, on 30 January 2014, a domestic mediation effort led by former president, Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo, was launched. Ouédraogo was supported by Paul Y. Ouédraogo, Archbishop of Bobo-Dioulasso; Samuel B. Yaméogo, president of the Federation of Churches and Evangelical Missions; and Mama Sanou, president of the Muslim community in Bobo-Dioulasso. The objective of this initiative was to establish a political dialogue between the CDP and the opposition to ease sociopolitical tensions. On 21 March 2014, Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara met with the three main former CDP figures: Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, Salif Diallo and Simon Compaoré. He also met with the opposition leader Zéphirin Diabré on 25 March 2014.23

These mediation efforts were not very successful, for various reasons. For example, the Ivorian president was perceived as being close to the Burkina Faso leadership, and was thus met with suspicion by the opposition. Also, the initiative by former president Ouédraogo encountered many difficulties, largely attributed to the irreconcilable positions of the various stakeholders and the lack of trust among them.

Moreover, in line with their various governance frameworks and early warning mechanisms, there were also calls on the international community – particularly ECOWAS, the AU, UN and Francophone countries – to intervene proactively to prevent the deterioration of the political impasse, which many believed could have repercussions on regional security. There were, indeed, some preventive diplomacy missions in Burkina Faso by the UN for West Africa (UNOWA) and ECOWAS in early 2014, as they became cognisant of the intentions of Compaoré to tweak the Constitution amid growing political tensions in the country.24 As an example, there was a joint mission by UNOWA and ECOWAS in Ouagadougou from 20 to 25 April 2014, to meet with the ruling and main opposition parties, as well as civil society.25 These minimal interventions had their limitations, and these institutions could only count on Compaoré’s assurance of political dialogue.26

Events after Compaoré

The military coup marred the people’s resolve against authoritarian rule. Both local and international calls for a swift return to civilian rule seem to have paid off, following the signing of the transitional charter on 17 November 2014 to provide the legal framework for a civilian-led transition. After weeks of negotiations between the army and the relevant stakeholders, a quasi-civilian transitional government was established with Michel Kafando, a former diplomat, as interim president and foreign minister, and Zida as prime minister and defence minister. A 90-member transitional council was established to serve as the country’s Parliament. The military also holds key posts, including the interior ministry, in the Cabinet.

While this may be seen as a compromise among Burkina Faso’s political class and the military to advance the transition process, it raises the critical issue that the military remains entrenched in politics, contrary to the principles of civil-military relations. Nonetheless, since the installation of the transition government, a modicum of calm has returned to the country, despite the existence of weak institutions. Following months of lengthy negotiations among stakeholders, presidential and legislative elections have been scheduled for 11 October 2015. Further, on 7 April 2015, some electoral reforms were announced to enhance the credibility of the upcoming elections. However, it can be argued that some of the reforms were targeted more at uprooting the remnants of the old regime – for example, a new policy barring all members of the former government and former allies of Compaoré from contesting the upcoming elections.27As the country continues to grapple with a political army and growing tensions between Zida and the top military leaders, the interim president announced some ministerial reshuffling in July 2015. Zida was relieved of his defence minister functions as part of the measures taken to ensure stability.28

Conclusion

The political crisis was not unforeseen, as the warning signals were glaring. However, there were a lack of effective proactive interventions at both the national and regional level. Various stakeholders have had their share of the blame for the political crises in 2014. It is important to emphasise the need for effective proactive responses to forestall crises when the early warning signs are clear, rather than reactionary responses by the international community. Certain critical issues may threaten future stability – for example, poverty and underdevelopment, the challenge of organising credible elections, and implementing reforms in the face of limited financial resources. Besides that, poor management of the disbandment of the former presidential guard could also pose a serious threat to the transition.29 As an example, the elite presidential guard, where Zida was formerly a senior commander, threatened to arrest him last month following attempts at curtailing their influence. There were also reports of gunfire from their barracks last month in an apparent warning to transitional leaders.30 There is need for collaborative efforts by both local and regional stakeholders to address these many challenges.

Endnotes

- The Guardian (2014) ‘Protesters Storm Burkina Faso’s Parliament’, 30 October, Available at: <http://www.theguardian.com> [Accessed 4 November 2014].

- Birikorang, Emma (2013) Coups d’état in Africa – A Thing of the Past? KAIPTC Policy Brief, 3.

- BBC News (2014a) ‘How Burkina Faso’s Blaise Compaoré Sparked His Own Downfall’, 31 October, Available at: <http://ww.bbcnews.com> [Accessed 7 November 2014].

- International Crisis Group (2013) Burkina Faso: With or without Compaoré, Times of Uncertainty. Africa Report, 205 (July).

- Burkina Faso’s Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2012. Compiled by the Constitute Project, Available at: <https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Burkina_Faso_2012.pdf> [Accessed 10 November 2014].

- Engels, Bettina (2015) ‘Political Transition in Burkina Faso: the Fall of Blaise Compaoré’. Governance in Africa, 2(1): 3, pp. 1–6, DOI: <http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/gia.ai>.

- ENCA (2014) ‘Burkina Faso Ruling Party Calls for Referendum on Term Limits’, Africa, 22 June, Available at: <http://www.enca.com/burkina-faso-ruling-party-calls-referendum-term-limits> [Accessed 8 November 2014].

- Institute for Security Studies (2014) Risks Ahead of the Constitutional Referendum in Burkina Faso. ECOWAS Peace and Security Report, 9 (August).

- International Crisis Group (2013) op. cit.

- BBC News (2014b) ‘Burkina Faso Army Announces Emergency Measures’, 30 October, Available at: <http://www.bbcnews.com> [Accessed 8 November 2014].

- Ibid.

- Dorrie, Peter (2012) ‘Burkina Faso: Blaise Compaoré and the Politics of Personal Enrichment’, Available at: <http://africanarguments.org> [Accessed 3 November 2014].

- Ibid.

- United Nations (2014) ‘Human Development Index’, Available at: <https://data.undp.org/dataset/Table-1-Human-Development-Index-and-its-components/myer-egms> [Accessed 10 August 2015].

- Wynne, Andy (2014) ‘Burkinabes Say: “Enough is Enough!”‘ Pambazuka News, 701, 4 November, Available at: <http://pambazuka.org> [Accessed 10 November 2014].

- BBC News (2014a) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- BBC News (2011) ‘Burkina Faso Soldiers Mutiny over Pay’, 15 April, Available at: <http://www.bbcnewc.com> [Accessed 7 November 2014].

- Institute for Security Studies (2014) op. cit.

- Hagberg, Sten (2014) ‘Burkina Faso: Is President Compaoré Finally on the Way Out?’ Think African Press, 14 January, Available at: <http://www.thinkafricanpress.org> [Accessed 10 November 2014].

- Elgie, Robert (2013) ‘Burkina Faso: Senate Elections’, Available at: <http://www.semipresidentialism.com/?p=3054> [Accessed 10 November 2014].

- Hagberg, Sten (2014) op. cit.

- Institute for Security Studies (2014) op. cit.

- United Nations (2014) Report of the Secretary-General on the activities of the United Nations Office for West Africa.

- United Nations Security Council (2014) ‘Briefing on Burkina Faso’, 4 November, Available at: <http://www.whatsinblue.org/2014/11/briefing-on-burkina-faso.php> [Accessed 10 August 2015].

- Bensah, K. Emmanuel (2014) ‘ECOWAS/UN Knew of Compaoré’s Intentions as Far Back as March 2014!’, Modern Ghananews, Available at: <http://www.modernghana.com/news/579925/> [Accessed 10 November 2014].

- Harsch, Ernest (2015) ‘Burkina Faso’s Electoral Reforms Test Fragile Transition’, 27 April, Available at: <www.worldpoliticsreview.com> [Accessed 10 August 2015].

- Reuters (2015) ‘Burkina Faso Reshuffles Government 3 Months before Elections’, 23 July, Available at: <www.reuters.com>.

- International Crisis Group (2015) Burkina Faso: Nine Months to Complete the Transition. Africa Report, 222 (28 January).

- Reuters (2015) op. cit.