Abstract

Inter-village land disputes confronted by the Ifakara Town Council – a local governing authority in Tanzania – arise from socio-economic complexities, poor boundary demarcation, and weak institutional frameworks, making litigation ineffective. Despite the prevalence of these conflicts, there is limited understanding of how Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms, particularly mediation, can address such issues in rural Tanzania. This study evaluates the applicability and effectiveness of ADR, with a focus on mediation, in resolving these disputes. Given the limitations of litigation, culturally appropriate ADR methods are essential for achieving sustainable conflict resolution. The research used a mixed-methods approach, collecting qualitative and quantitative data through interviews, document reviews, and questionnaires from stakeholders in four villages. The findings show that while ADR, especially mediation, is valued for its flexibility and cultural relevance, its effectiveness is limited by challenges such as poor boundary demarcation, bureaucratic delays, weak institutional capacity, and resistance from disputing parties. The study concludes that to enhance ADR effectiveness, structural issues like boundary demarcation and institutional weaknesses must be addressed. It recommends improving boundary clarity, strengthening institutional frameworks, increasing community awareness, and establishing monitoring systems to ensure compliance with ADR outcomes. These measures could promote sustainable land governance in Ifakara and similar regions across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: Inter-village land disputes, Alternative Dispute Resolution, Mediation, Ifakara Town Council, Tanzania, Dispute resolution mechanisms

1. Introduction

Land is a critical resource for human existence and socio-economic progress, providing the foundation for industrial development, housing, and agriculture (Haberl, 2015; Wehrmann, 2017). As the global population rises, competition for land intensifies, fuelled by urbanisation, infrastructural development, and resource extraction (Avery, 2013; Bruce and Boudreaux, 2013). Consequently, disputes over land ownership and usage have become more frequent and intense (Emanuel and Ndimbwa, 2013). If left unresolved, these disputes may escalate into larger conflicts, undermining societal cohesion and threatening economic stability (Conteh and Yeshanew, 2016).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, land disputes are particularly prevalent due to the dual nature of land as both an economic resource and a symbol of cultural identity (Home, 2020; Peters, 2021). In Tanzania, inter-village land disputes recur frequently, affecting rural structures such as the Ifakara Town Council. The disputes often arise from competing claims rooted in historical grievances, ambiguous land tenure systems, and conflicting land use practices (Rubakula, Wang and Wei, 2019). These disputes often lead to prolonged tensions and occasional violence, sometimes remaining unresolved for years (Lamin, 2018).

The complexity of inter-village land disputes in Ifakara stems from various factors, including poor boundary demarcation, land scarcity due to population growth, and administrative inefficiencies such as corruption and inadequate enforcement of land laws (Verplanke and McCall, 2010; Lierk, 2018; Saruni, Urassa and Kajembe, 2018). Moreover, historical land allocation policies that favoured certain groups have perpetuated conflicts (Mtengeti and Mwambene, 2022). Understanding these root causes is crucial for effectively addressing the issues at hand.

The problem of land conflicts is not unique to Tanzania; studies across Africa have documented similar challenges with land dispute resolution, which often reflect broader systemic issues within land governance. For instance, Ibrahim et al. (2022) identified that in Ghana, the effectiveness of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) is often hindered by limited awareness, institutional weaknesses, and inadequate enforcement of agreements. Similarly, Ntuli (2018) emphasised that despite the cultural relevance of ADR in many African contexts, the challenges of inconsistent implementation, legal recognition, and community buy-in have limited its success. Kalabamu (2021) further notes that the effectiveness of ADR in Botswana is influenced by local governance structures and the extent to which ADR processes are embedded within formal legal systems. These studies underscore that while ADR has been widely promoted as a solution to land conflicts, its practical application remains fraught with challenges that vary by region and context.

Against this backdrop, ADR mechanisms – such as mediation, negotiation, and arbitration – have been advocated as promising alternatives to litigation for managing land disputes in Tanzania (Hassall, 2005; Ampeire, 2017). ADR offers flexibility, cost-efficiency, and the potential for culturally relevant, community-driven solutions (Buscagila and Stephan, 2012; Kalabamu, 2021). However, despite its availability in Ifakara, land disputes between villages like Lungongole and Sagamaganga have remained unresolved for over a decade, and conflicts between Sole and Mang’ula A have persisted for 14 years. This raises questions about the underlying challenges limiting ADR’s effectiveness in this region (Mbonde, 2015; Mushi and Kamugisha, 2023). Understanding why ADR processes have not fully addressed these long-standing conflicts is crucial to determining how they can be improved.

The purpose of this study is to assess the applicability of ADR mechanisms, particularly mediation, in resolving inter-village land disputes in Ifakara. It explores the underlying causes of these conflicts and evaluates how ADR processes can be better aligned with the needs of the local communities. Additionally, the study examines the legal and regulatory framework governing land disputes in Tanzania, focusing on key legislative instruments such as the Village Land Act No. 5 of 1999 and the Local Government (District Authorities) Act of 1982 (Kishenyi, 2017). Understanding these frameworks is essential, as they influence the roles of local land institutions, including Village Land Councils, Ward Tribunals, and District Land and Housing Tribunals, in addressing disputes (Mwakaje, 2022; Ringo, 2023).

While ADR mechanisms have been studied extensively across Africa, limited research has focused on their specific application in rural Tanzania. This gap underscores the necessity of this study, which seeks to contribute to the broader literature on land conflict resolution by offering a detailed examination of ADR practices in Ifakara. The findings provide insights into the factors that facilitate or hinder the success of ADR in rural Tanzania, with implications for improving land governance and conflict resolution strategies across Sub-Saharan Africa (Ntuli, 2018; Home, 2020; Kalabamu, 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2022).

Ultimately, this study aims to explore how ADR mechanisms can be rendered more effective in managing inter-village land disputes. By identifying key challenges and offering recommendations for reform, it seeks to contribute to the development of more robust, sustainable approaches to land conflict resolution that are both legally sound and culturally sensitive.

2. Literature Review

Land disputes, especially those that involve multiple parties contesting property rights, represent a significant challenge in regions where land is a scarce and highly contested resource, such as Sub-Saharan Africa. The complexity of these disputes often escalates due to inadequacies in traditional dispute resolution mechanisms, including litigation, which are frequently criticised for being time-consuming, costly, and inaccessible to marginalised populations (Schomerus and Rigterink, 2021; Nkonya, Mirzabaev and Von Braun, 2022). This situation underscores the necessity of distinguishing between various conflict resolution processes, including legal or common law litigation, administrative dispute resolution, traditional dispute resolution, and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms (Anyanwu and Aluko, 2022; Williams, 2023). A deeper understanding of these processes is vital to addressing the unique land conflict dynamics in regions like Ifakara, Tanzania.

ADR encompasses several processes, with negotiation, mediation, and arbitration being the most commonly recognised forms. Negotiation represents the most informal aspect of ADR, wherein the parties involved in a dispute communicate directly with one another to reach a mutually acceptable agreement. In this context, disputants retain full control over both the process and the outcome (Fisher, Ury and Patton, 2011). The practice of negotiation is prevalent in traditional African dispute resolution systems, where community elders often play an instrumental role in encouraging disputants to amicably resolve conflicts before resorting to the involvement of third parties. This community-based approach highlights the importance of maintaining social harmony and cohesion, which is vital in societies where communal ties are significant.

Mediation, as another key form of ADR, involves a neutral third party, known as the mediator, who facilitates communication between disputants to help them reach a voluntary agreement. The mediator does not impose a solution; instead, they guide the parties towards a mutually acceptable resolution (Moore, 2014). In many African contexts, mediation aligns closely with traditional dispute resolution practices where respected community leaders or elders intervene to mediate conflicts. This practice reflects a broader cultural acceptance of mediation as a means of resolving disputes, reinforcing social ties, and ensuring community stability.

In contrast, arbitration presents a more formal process in which a neutral third party, referred to as the arbitrator, listens to the disputants and makes a binding decision regarding the outcome of the dispute (Redfern and Hunter, 2021). Unlike mediation, where the parties retain control over the resolution process, arbitration empowers the arbitrator to impose a solution. In some African societies, arbitration has historically been performed by local chiefs or kings, whose decisions were deemed final and binding. This structured approach to dispute resolution is vital in understanding how formal and informal systems can coexist, offering multiple pathways for conflict resolution in communities facing land disputes.

The concepts of ADR resonate deeply within the African context, closely resembling traditional methods of conflict resolution that emphasise consensus-building, communal harmony, and restorative justice (Moyo and Chambati, 2023). Traditional African dispute resolution methods often integrate elements of both mediation and arbitration, with community elders typically mediating initial discussions to encourage voluntary settlements. However, if mediation efforts fail, these same elders may transition to an arbitration role and provide final judgements that all parties accept. This overlap between ADR and traditional dispute resolution is crucial for understanding how ADR can be tailored to fit local contexts.

The emphasis on communal relationships inherent in African societies often positions mediation as a preferred method for resolving disputes. Mediation fosters the restoration of social harmony, avoiding the adversarial nature of litigation or the rigid procedures of formal arbitration. Traditional leaders, who frequently assume dual roles as mediators and arbitrators, help blur the lines between these forms of ADR in practice, demonstrating the flexibility and cultural relevance of these approaches in addressing land conflicts. The alignment of ADR practices with community values is particularly significant in rural areas where formal legal systems may be perceived as foreign or inaccessible. Consequently, ADR, particularly negotiation and mediation, emerges as a more acceptable and effective means of resolving land disputes in regions like Ifakara, where conflicts are deeply rooted in community relationships and cultural norms.

Traditional dispute resolution mechanisms often intersect with ADR; yet they remain distinct because of their reliance on customary practices and community norms. Traditional dispute resolution encompasses culturally rooted methods that can either complement or conflict with formal ADR processes (Moyo and Chambati, 2023). Recognising this distinction is essential for understanding how various approaches can coexist or compete in the landscape of land dispute resolution.

Globally, ADR has shown promise in diverse contexts, including countries such as Argentina, South Africa, and Bangladesh (García, 2021; Singh and Mbatha, 2022; Rashid and Rahman, 2023). In Argentina, for instance, ADR has played a pivotal role in resolving urban property disputes by integrating community mediation into formal legal systems (García, 2021). In South Africa, the application of ADR in land reform processes has facilitated mediation between landowners and tenants, underscoring the potential for ADR to enhance access to justice (Singh and Mbatha, 2022). In Bangladesh, the successful implementation of ADR in rural areas illustrates how these mechanisms can address land disputes where formal legal systems are often perceived as corrupt and inaccessible (Rashid and Rahman, 2023). These examples highlight ADR’s capacity to improve access to justice for marginalised populations struggling to navigate complex legal frameworks (Chitkara, 2023).

In Uganda, community-based mediation addresses land tenure disputes effectively by integrating traditional dispute resolution practices that foster dialogue and understanding, promote peaceful coexistence in rural settings, and strengthen community ties, while also addressing historical grievances related to land ownership and tenure security (Lwanga, 2018; Kansiime, 2019; Nakayiza, 2019; Ndangiza and Turyamuhweza, 2020; Wamala, 2020; Kairuki and Ddaaki, 2021). This success is mirrored in Kenya, where ADR has played a crucial role in addressing post-election land disputes by incorporating local customs and traditional leadership into the mediation process (Omondi and Ochieng, 2022).

Despite these successes, the effectiveness of ADR is not without challenges. Its success is often hindered by inadequate institutional capacity, resistance from parties involved in disputes, and a general lack of trust in the ADR process (Juma, 2021a; Maina and Gathumbi, 2022). In Kenya, Juma (2021b) highlights the shortage of trained mediators and the absence of legal recognition for ADR outcomes, which frequently leads to the resurgence of conflicts. Similarly, Kamau (2009) argues that the superimposition of Western ADR methods onto African societies often ignores local sociocultural dynamics, leading to resistance and reduced effectiveness. Such resistance often stems from traditional practices for conflict resolution perceived as more aligned with communal norms (Richard, 1939).

In Tanzania, the government has acknowledged the need for more effective land dispute resolution mechanisms and has implemented reforms to promote the use of ADR. These reforms include establishing legal frameworks and institutions designed to facilitate land dispute resolution through ADR processes (Kweka, 2023). Key institutions, such as Village Land Councils, Ward Tribunals, and District Land and Housing Tribunals play pivotal roles in mediating land disputes at the community level (Mwakaje, 2022). However, the persistent nature of inter-village land disputes in certain regions, such as Ifakara, raises concerns about the overall effectiveness of these mechanisms (Mtui, 2023). Maro (2022) raises similar concerns, noting that the lack of sustained government support and clear guidelines for ADR practitioners contributes to the limited success of ADR in Tanzania. Furthermore, Shemdoe and Kihamba (2023) highlight the impact of political factors, indicating that local power dynamics often skew the dispute resolution process, resulting in biased outcomes.

Research has underscored several challenges that continue to impede the successful application of ADR in Tanzania. These challenges include poor implementation of ADR agreements, a lack of expertise among mediators, and political influences that can distort the dispute resolution process (Maro, 2022; Shemdoe and Kihamba, 2023). These findings align with those of Anyanwu and Aluko (2022), who identified similar challenges in Nigeria, where the effectiveness of ADR is often undermined by weak enforcement mechanisms and political interference. Comparatively, in Ghana, Mensah (2023) contends that the effectiveness of ADR is closely linked to the level of community involvement and the presence of strong institutional support, suggesting that enhancing these factors could improve ADR outcomes in Tanzania.

The role of gender in ADR processes has gained increasing recognition in the literature. Mulyungi and Mwende (2022) argue that including women in mediation teams has led to more equitable outcomes in land disputes, particularly in patriarchal societies where women’s land rights are often marginalized. Similarly, research by UN Women (2017) emphasizes the importance of gender-sensitive practices in improving ADR outcomes, particularly for women. This study found that equitable approaches not only enhance satisfaction rates among female disputants but also contribute to more sustainable peace in conflict-prone areas. These insights underline the critical importance of incorporating diverse perspectives into ADR processes to enhance their fairness, inclusivity, and overall effectiveness in resolving conflicts.

In conclusion, the literature on ADR reveals a complex interplay of traditional practices, community dynamics, and institutional challenges that shape the landscape of land dispute resolution in Sub-Saharan Africa. While ADR presents a viable alternative to litigation, particularly in culturally rich contexts like Ifakara, its effectiveness hinges on addressing the underlying structural issues and fostering community engagement. By building on the strengths of both traditional and modern dispute resolution mechanisms, stakeholders can create more inclusive and effective pathways for resolving land conflicts, thereby promoting sustainable land governance in the region.

3. Study area

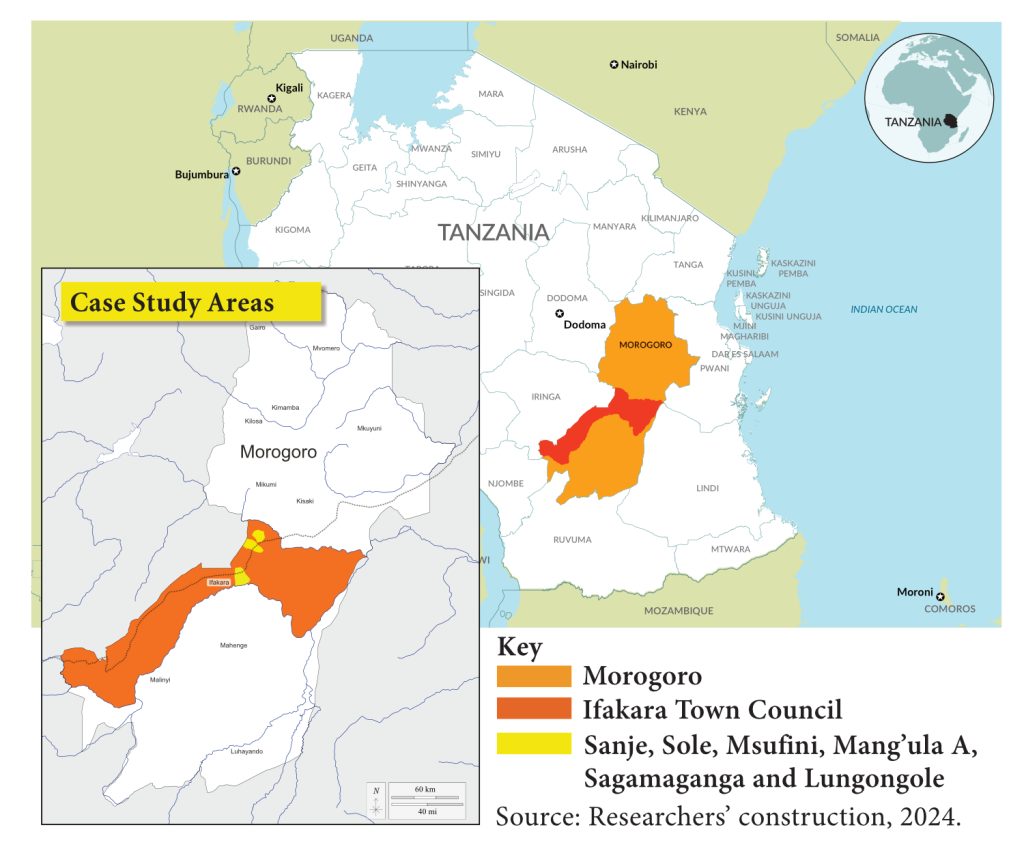

The study focuses on the Ifakara Town Council, located in the Morogoro region of Tanzania, specifically within the Kilombero District (see Figure 1). Ifakara is one of nine local government authorities in this region and is bordered by several districts: Kilombero District Council to the north, Ulanga District to the south-east along the Kilombero River, and Kilolo to the north-west. The town council encompasses parts of the Kilombero Valley and the Rufiji Basin, extends into the Selous Game Reserve, and is adjacent to the Udzungwa Mountains National Park.

Geographically, Ifakara is positioned between latitudes -8º 07’ 59.99’’ S and longitudes 36º 40’ 59.99’’ E. The total area of the council spans approximately 7 205 km2. The administrative structure, the Ifakara Town Council, includes one division subdivided into nine wards, 11 villages, 33 streets, and 64 sub-villages.

According to the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (2022), the population of Ifakara stands at 290,424, with 14 023 males and 149 401 females, resulting in a population density of 40.31 inhabitants per km2. Agriculture plays a pivotal role in the livelihoods of the residents, with the majority engaged in farming activities. Key commercial crops cultivated in the area include paddy, coconuts, sunflowers, and various legumes.

The socio-economic dynamics of Ifakara are influenced by its geographical features and agricultural practices, contributing to both opportunities and challenges in land use and management. Understanding these aspects is crucial for addressing the land conflicts explored in this study, particularly given the area’s reliance on agricultural resources and the community’s interaction with traditional dispute resolution mechanisms.

Figure 1: Ifakara Town Council location map

4. Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative research methods, which is widely supported in the literature for its ability to provide a balanced and in-depth understanding of complex social issues (Bryman, 2016; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). This dual approach provided a well-rounded understanding of the research problem by combining the depth of qualitative insights with the breadth of quantitative data.

The qualitative component involved unstructured interviews and document reviews, techniques highly recommended for exploratory research in dispute resolution contexts (Kvale, 2007; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015). These methods were crucial in exploring the nature of inter-village land disputes, understanding the perceptions and experiences of key stakeholders, and identifying the challenges encountered in the application of ADR mechanisms. The qualitative data provided rich, detailed information essential for understanding the context and complexities of the disputes.

The research was anchored in a case study approach, which is considered effective for in-depth investigation of specific geographical areas and social phenomena (Yin, 2014). The study focused on four selected villages in Ifakara: Lungongole, Sagamaganga, Sole, and Mang’ula A. The authors chose these villages based on their history of ongoing inter-village land disputes, despite the application of various dispute resolution mechanisms. This geographic area is characterised by a population engaged predominantly in agriculture, where competition for fertile land, water resources, and grazing areas creates tension between neighbouring communities. This scenario provides a relevant setting for studying ADR mechanisms to ensure effective conflict resolution mechanisms are applied to foster cooperation among communities.

Sampling techniques for the study combined purposive and snowball sampling, methods recognised for their utility in selecting knowledgeable participants and expanding sample sizes through referrals (Noy, 2008; Patton, 2015). The study used purposive sampling to identify key participants, such as village executive officers, land officers, and land surveyors, who possessed relevant knowledge and experience in land dispute resolution. Their insights were crucial for understanding the application of ADR mechanisms in the study area. Snowball sampling facilitated the identification of additional participants through referrals from initial contacts, ensuring that participants with direct experience in the dispute resolution process were included in the study.

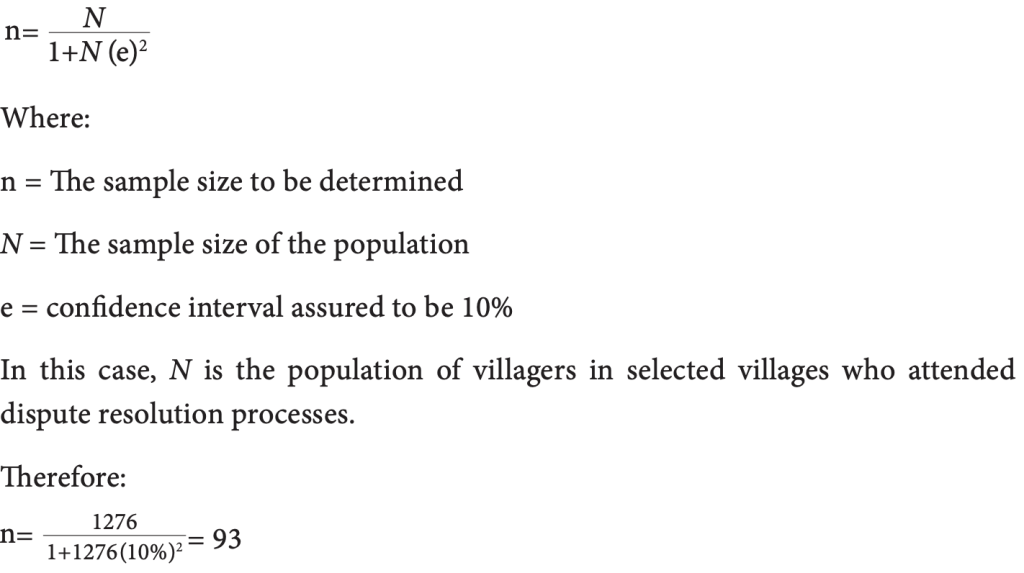

The sample size for the known population was calculated using Slovin’s Formula (Equation 1), resulting in 93 participants: 8 village executive officers, 75 villagers, 5 land officers, and 5 land surveyors. This formula (Equation 2) was applied to ensure adequate representation of the population involved in the land disputes (Tejada and Punzalan, 2012).

Equation 1

Data collection involved gathering information from both primary and secondary sources, following established guidelines for triangulating data to enhance the reliability of findings (Creswell, 2014). The authors conducted unstructured interviews in both Swahili and English, depending on the informant’s preference, to ensure clear communication and accommodate linguistic diversity (Bryman, 2016). The research team distributed questionnaires containing closed-ended questions to villagers to gather quantitative data on their experiences with land dispute resolution mechanisms. The researchers obtained secondary data through document review of relevant studies, reports, statutes, and government records, providing essential context and complementing primary data.

The research team analysed the collected data using thematic analysis for qualitative data and descriptive statistical analysis for quantitative data. Thematic analysis, a widely used method for identifying patterns in qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006), involves coding the data, identifying recurring themes, and interpreting findings. The research team analysed the quantitative data using descriptive statistics, a common approach in survey-based research, with results presented in tables, figures, and charts (Field, 2018).

Ethical considerations were paramount in this study, in line with established ethical standards (Israel and Hay, 2006). The researchers obtained informed consent from all participants and assured them of the confidentiality of the information provided. The study adhered to ethical guidelines regarding protecting participants’ privacy and reporting findings accurately. The researchers maintained participants’ anonymity and stored all data securely.

This methodological approach, grounded in established literature, provided a robust framework for investigating the application and effectiveness of ADR mechanisms in resolving land disputes in the rural town of Ifakara.

5. Conceptual and theoretical frameworks

This study employs a conceptual framework grounded in various theoretical perspectives to explain the emergence of land disputes and the role of ADR in mitigating them. Central to this understanding is conflict theory, which highlights the impact of resource control, power imbalances, and class struggles in driving societal conflicts. As articulated by Karl Marx and later expanded by sociologists like Max Weber (Giddens et al., 2017; Weber, 2019), this theory explains how disputes in places like Ifakara stem from the unequal distribution of land and resources. Marginalised groups, such as indigenous or poorer communities, often find themselves in conflict with dominant entities like wealthy landowners or government bodies. Fischer (2007) points out that land in developing economies serves not only as a key resource for survival but also as a marker of social standing, causing disputes over it to be deeply rooted in social inequities.

In parallel, John Rawls’ theory of justice (1971) emphasises the need for fairness and equitable treatment in the distribution of resources in society (Friedman, 2018; Harsanyi, 2018). Rawls’ idea of the ‘veil of ignorance’ and his concept of justice as fairness support the argument that any dispute resolution process, including ADR, must be impartial and inclusive. Mediation, a core tool in ADR, serves as a neutral platform where justice and fairness can prevail. In the context of land disputes in Ifakara, mediation allows both parties to explore mutually agreeable solutions while prioritising fairness. Rawls’ emphasis on justice reinforces the value of ADR mechanisms in fostering social harmony by allowing disputes to be resolved in a manner that respects the dignity and rights of all parties involved.

Complementing this framework is the theory of social exclusion, which examines how certain groups are systematically denied access to essential resources (Lenoir, 1974; Silver, 1994; Levitas, 1998; Byrne, 1999; De Haan, 1999). This exclusion perpetuates cycles of deprivation and isolation. In Ifakara, land disputes often involve socially excluded groups, such as impoverished or indigenous communities, who are particularly vulnerable to losing their land as a result of unclear boundaries, lack of institutional support, and exploitative practices. De Haan (1999) defines social exclusion as a multidimensional process that restricts access to crucial resources like land, thereby making ADR a potential means of reintegrating these marginalised groups into the broader land governance framework.

Additionally, this study builds on Homer-Dixon’s (1994) work on resource scarcity and environmental stress, recognising that population pressure is a key factor driving land disputes in rural Tanzania. Increasing demand for arable land, poor boundary demarcation, and weak governance structures exacerbate these conflicts. Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) theory of Common Pool Resources (CPR) provides further insight into how disputes over shared resources like land can be managed better through community-based ADR strategies. By involving local stakeholders, ADR mechanisms can address the root causes of resource conflicts more effectively than top-down approaches.

The theoretical foundation for ADR itself is rooted in the work of scholars such as Moore (2014) and Bush and Folger (1994), who argue that mediation fosters interest-based negotiation. This approach encourages conflicting parties to work collaboratively to find mutually acceptable solutions. In rural settings like Ifakara, ADR’s cultural relevance is reinforced by traditional practices of community dialogue and problem-solving. Thus, ADR not only helps resolve land disputes but also works to restore community relationships that may have been fractured by conflict.

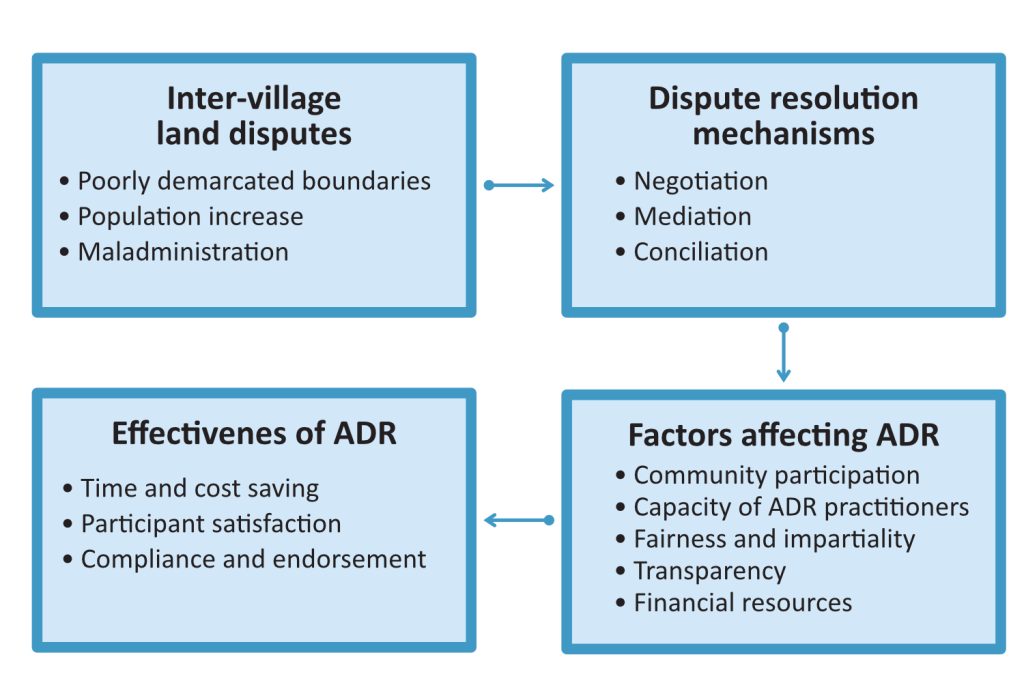

The conceptual framework developed for this study, as illustrated in Figure 2, identifies various causes of inter-village land disputes, including poorly demarcated boundaries, scarcity of land, increasing population pressure, maladministration, and inadequate information systems. These factors are crucial for understanding the underlying issues that lead to disputes and for tailoring appropriate ADR strategies. The framework also outlines various ADR strategies, such as negotiation, mediation, conciliation, and arbitration, which serve as critical tools for resolving disputes. The effectiveness of these strategies, however, hinges on several factors, including community participation, the skill level of ADR practitioners, financial resources, and transparency throughout the resolution process.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of the study

In addressing land disputes through ADR, community involvement plays a vital role in enhancing the effectiveness of resolution efforts. When community members participate actively in the resolution process, it fosters a sense of ownership and accountability, which can lead to more sustainable outcomes. Additionally, the competency and training of ADR practitioners are paramount; well-trained mediators and arbitrators can influence the resolution process significantly by facilitating constructive dialogue and ensuring fairness. Moreover, ensuring transparency in the resolution process and allocating adequate financial resources can make ADR more accessible, time-efficient, and satisfactory for all parties involved.

Ultimately, this conceptual framework integrates diverse theoretical perspectives to understand the interplay between land disputes and ADR mechanisms. By addressing the root causes of disputes and highlighting the importance of community engagement and skilful mediation, this framework aims to develop effective strategies for resolving inter-village land conflicts in Ifakara and beyond.

6. Findings and Discussion

This section analyses the study’s findings on the applicability of ADR mechanisms in resolving inter-village land disputes by the Ifakara Town Council. The results are organised to align with the study’s objectives, supported by data from interviews, questionnaires, and secondary sources.

Objective 1: Understanding the Nature and Magnitude of Land Disputes

The prevalence of land disputes in Ifakara remains a significant concern, especially in villages like Lungongole, Sagamaganga, Sanje, Msufini, Sole, and Mang’ula A. These disputes have persisted for years, with increasing frequency and severity. Out of the 93 targeted participants, 86 acknowledged the existence of these conflicts, with boundary disputes between villages being the most common. From the interviews conducted, the primary causes of these disputes include inadequate boundary demarcation, inconsistent survey maps, land encroachment, maladministration, and political interference. Other disputes also relate to land allocation, ownership, and changes in land use.

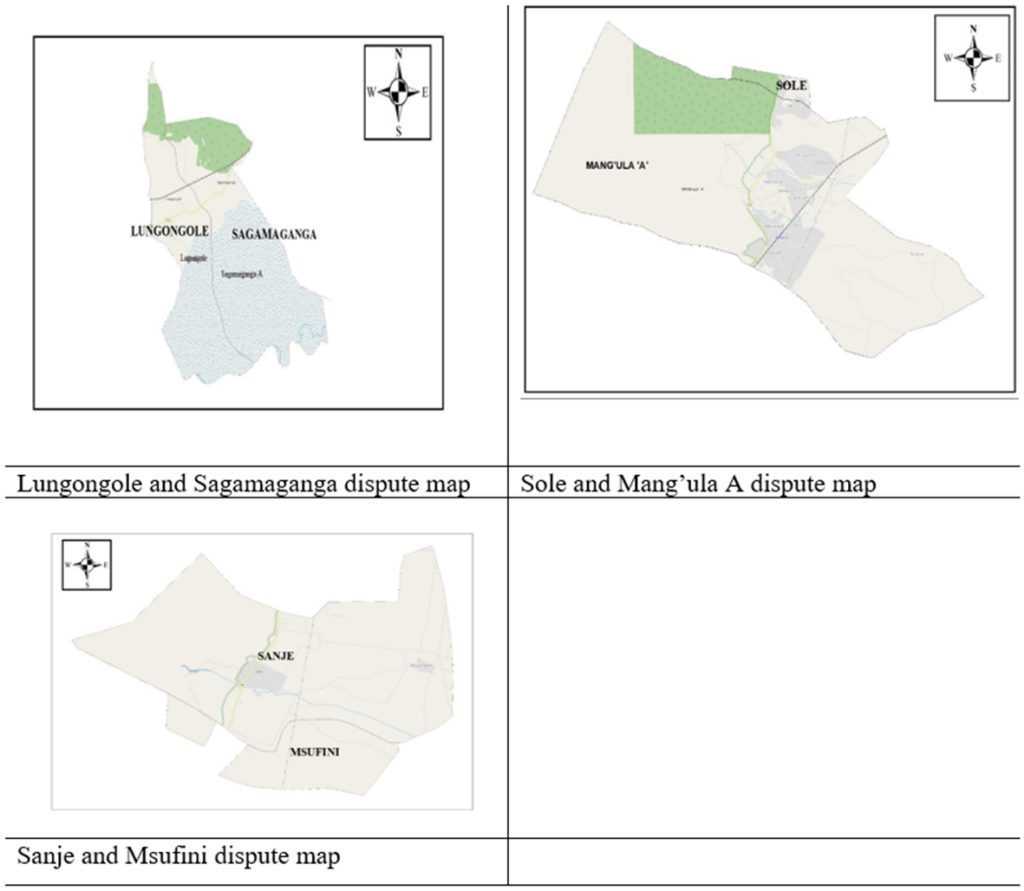

The visual representations of disputes between Lungongole and Sagamaganga, Sole and Mang’ula A, and Sanje and Msufini (Figure 3) provide insights into the complexity of boundary disagreements. These maps show how natural landmarks, such as rivers and forests, have shifted over time, further complicating boundary disputes.

Figure 3: Ifakara inter-village land dispute map

Participant breakdown of the 86 respondents who participated in the study:

- Village executive officers: 8

- Villagers: 68

- Land officers: 5

- Land surveyors: 5

This breakdown shows the diversity of respondents, ensuring a well-rounded analysis of the disputes from different perspectives.

Objective 2: Investigating the Causes of Land Disputes

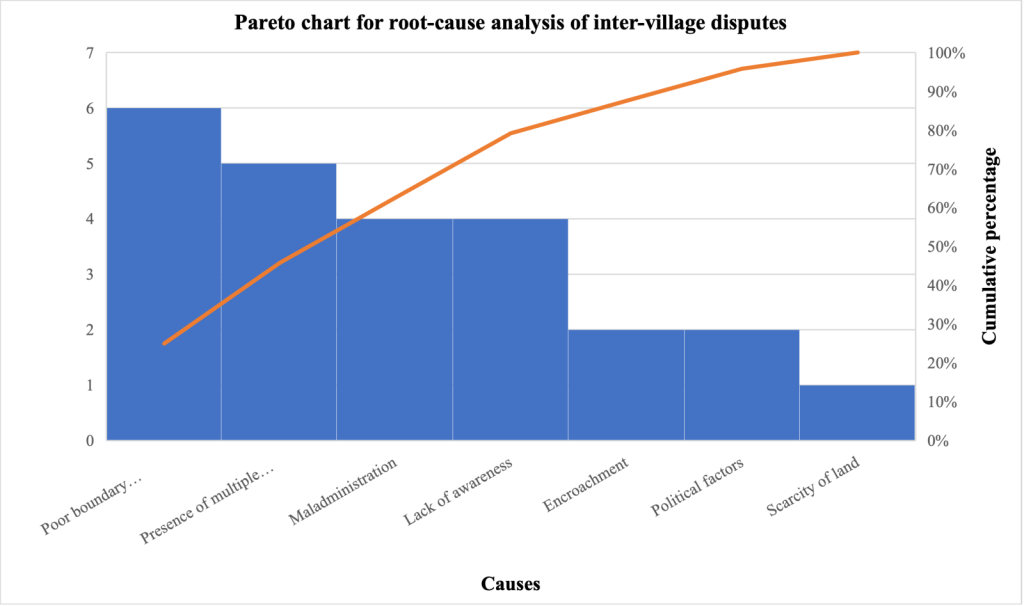

The main causes of inter-village land disputes are outlined in Figure 4, a Pareto chart highlighting the root causes identified by respondents. Poor boundary demarcation, cited by 25% of respondents, emerged as the most prevalent issue, followed by conflicting survey maps (20.8%). Other factors include maladministration and lack of awareness of land laws (16.7% each), encroachment, political interference, and land scarcity.

Figure 4: Pareto chart for root-cause analysis of inter-village land disputes

This figure illustrates how poor boundary demarcation and conflicting survey maps are the leading causes of land disputes.

Qualitative interviews provided additional insights. For example, a village executive from Sole explained: “We rely on the old maps that are no longer accurate. The changes in the river’s path and new settlements have made it difficult to identify the actual village boundaries.”

Similarly, a land officer from Mang’ula A described administrative challenges: “There is confusion because of overlapping maps from different surveying periods. Villages are not well-informed about their legal boundaries, which leads to repeated disputes.”

These testimonies emphasise the significant administrative and environmental challenges contributing to land disputes. As many causes are interrelated, addressing one issue, such as boundary demarcation, could alleviate others, like encroachment and conflicting surveys.

Objective 3: Evaluating the Effectiveness of ADR Mechanisms

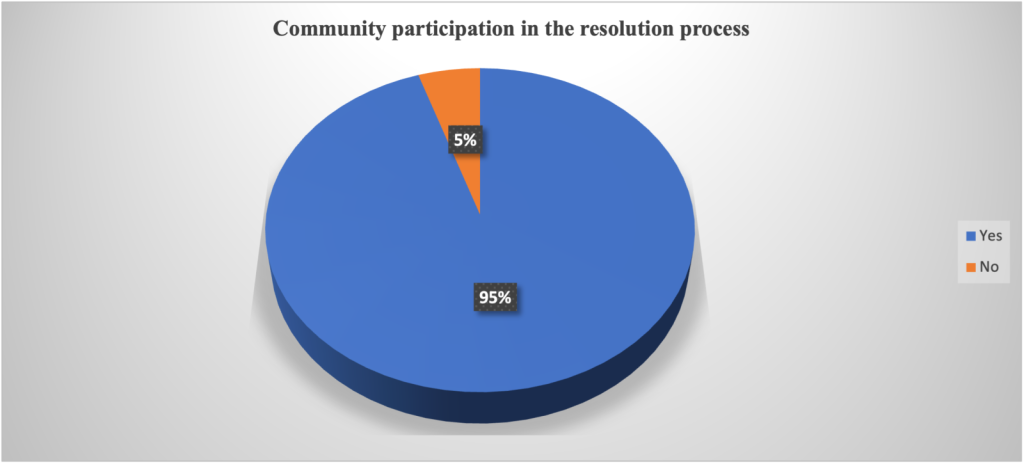

The study found that ADR mechanisms, particularly mediation, are widely used by the Ifakara Town Council. Of the 86 respondents, 95% reported participating in ADR processes (see Figure 5). This high level of community involvement demonstrates the accessibility of ADR mechanisms to the local population. However, satisfaction with these processes remains low, with only 5.4% of respondents expressing complete satisfaction with the outcomes. Dissatisfaction stems from delays in the process and reluctance by mediators to finalise decisions.

Figure 5: Community participation in the inter-village land dispute resolution

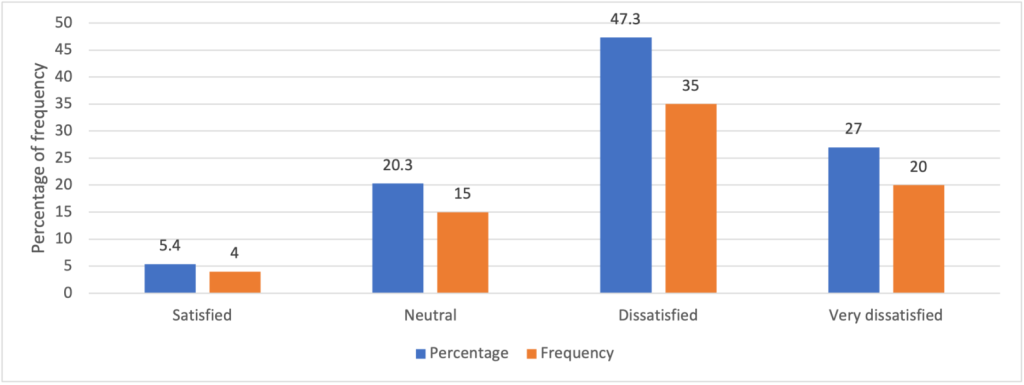

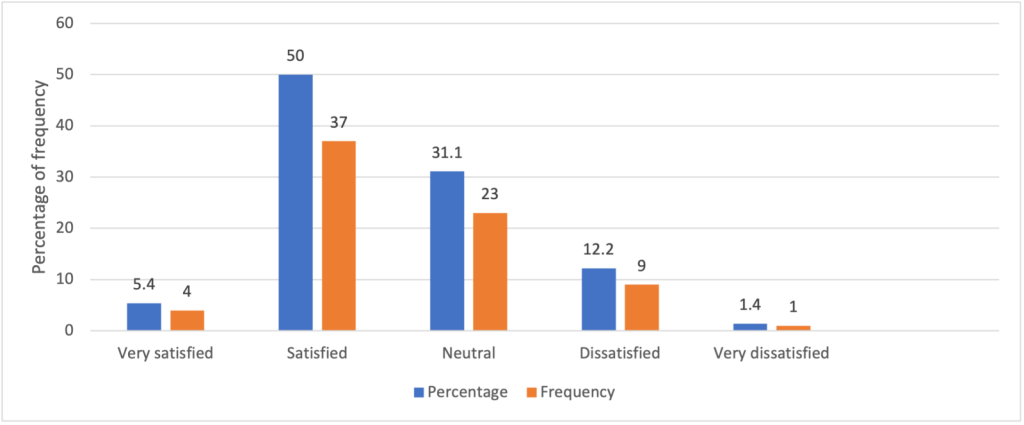

The study also assessed the extent of satisfaction regarding the overall dispute resolution process. Figure 6 shows that 5.4% of the respondents expressed satisfaction, 20.3% remained neutral, 47.3% indicated dissatisfaction, and 27% reported being very dissatisfied. This suggests that a significant majority of respondents are dissatisfied with the dispute resolution process, highlighting the need for improvements in its effectiveness and efficiency.

Figure 6: Satisfaction level with the overall dispute resolution process

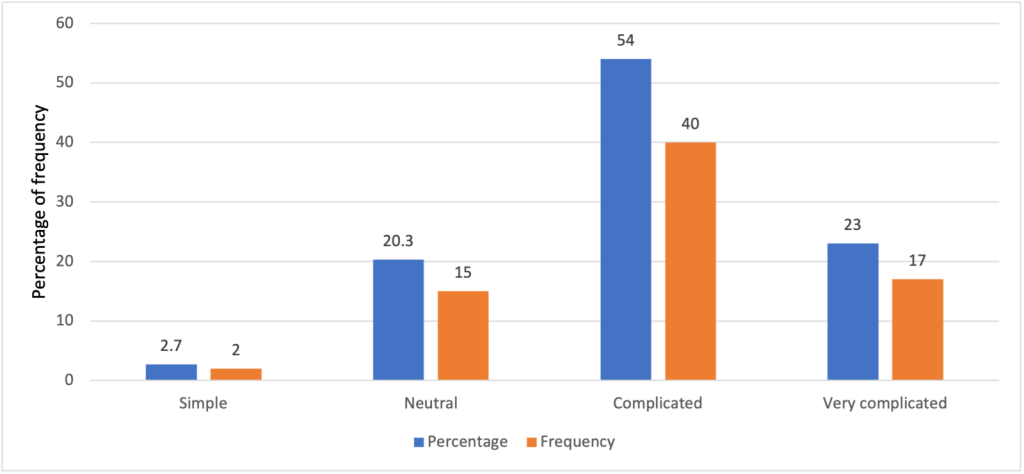

To assess the simplicity of the dispute resolution process, respondents were asked to rate their experiences, particularly focusing on bureaucratic delays, mediator inefficiencies, and the lack of timely feedback. This aimed to determine whether the process of resolving inter-village land disputes was straightforward or burdensome for the parties involved, considering the procedures, time requirements, and institutional capacity of the mediators. The study revealed that 54% of respondents found the ADR process complicated (see Figure 7), with the key issues being bureaucratic delays, inefficiencies among mediators, and untimely feedback.

Figure 7: Extent of simplicity of the land dispute resolution process

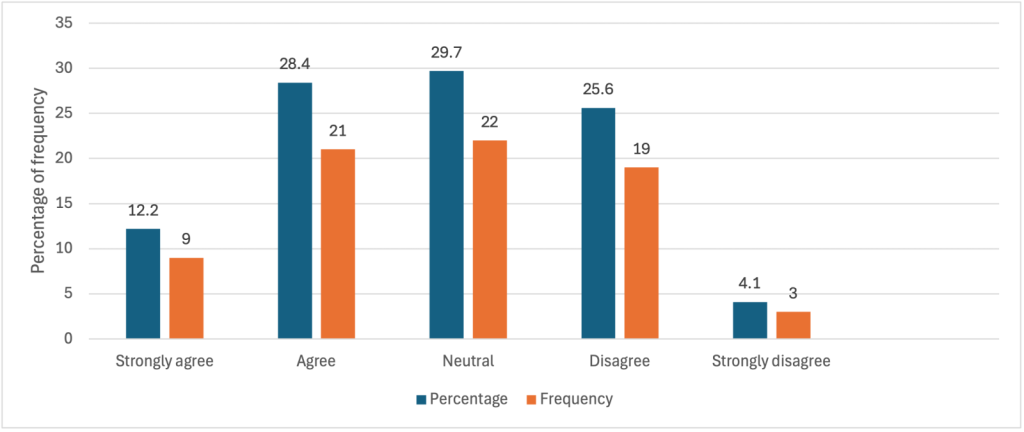

Additionally, to assess neutrality and impartiality, respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction. The goal was to evaluate whether mediators were neutral and independent from the disputing parties, and if all relevant stakeholders were adequately represented and given a voice during the resolution process. The data showed that 50% of respondents were satisfied with the neutrality and impartiality of the mediators (see Figure 8), while 31.1% remained neutral, citing occasional delays in communication that created the impression of bias.

Figure 8: Neutrality and impartiality in the dispute resolution process

This figure illustrates that while half of the respondents found mediators to be impartial, others were concerned with occasional delays that created a perception of bias.

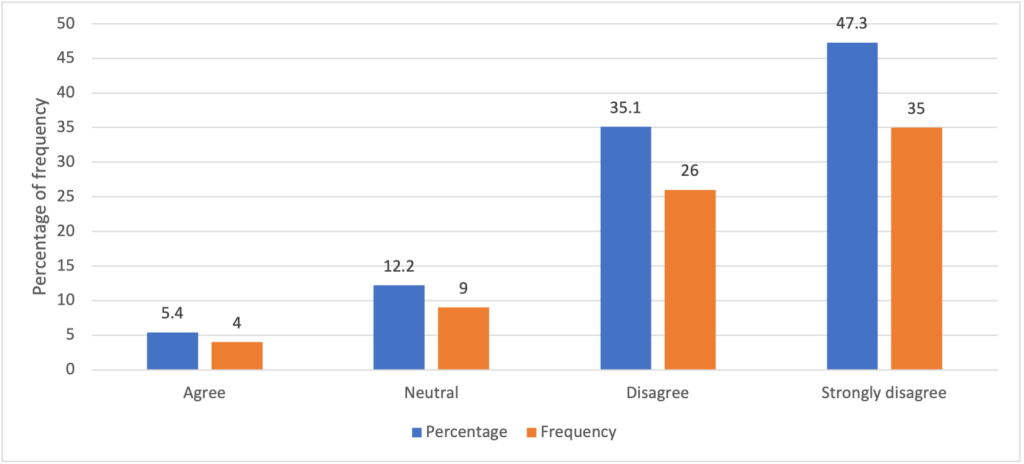

To evaluate the integration of traditional dispute resolution practices, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement on whether these practices were incorporated into the dispute resolution practices. The aim was to assess if the mediators engaged with village elders, traditional authorities, and community members to understand their perspectives, concerns, and preferences regarding the use of traditional methods in resolving land disputes. The findings revealed that 40.6% of respondents agreed that traditional practices were considered (see Figure 9), while some expressed concerns about the exclusion of elders from the processes.

Figure 9: Alignment with traditional dispute resolution practices

Objective 4: Identifying Challenges in ADR Implementation

To assess the challenges in ADR implementation, respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with the dispute resolution process. This aimed to determine whether the actors involved provided comprehensive information, such as the scheduling of meetings and offering clear explanations of the overall dispute resolution process. It also sought to evaluate whether clear channels were established for community members to provide feedback and raise concerns. Enforcement of resolutions emerged as a critical issue, with 82.4% of respondents indicating that there were no mechanisms in place to monitor or enforce agreed-upon resolutions (see Figure 10). This lack of enforceability allowed disputes to persist, even after mediation.

Figure 10: Enforcement of agreed resolutions

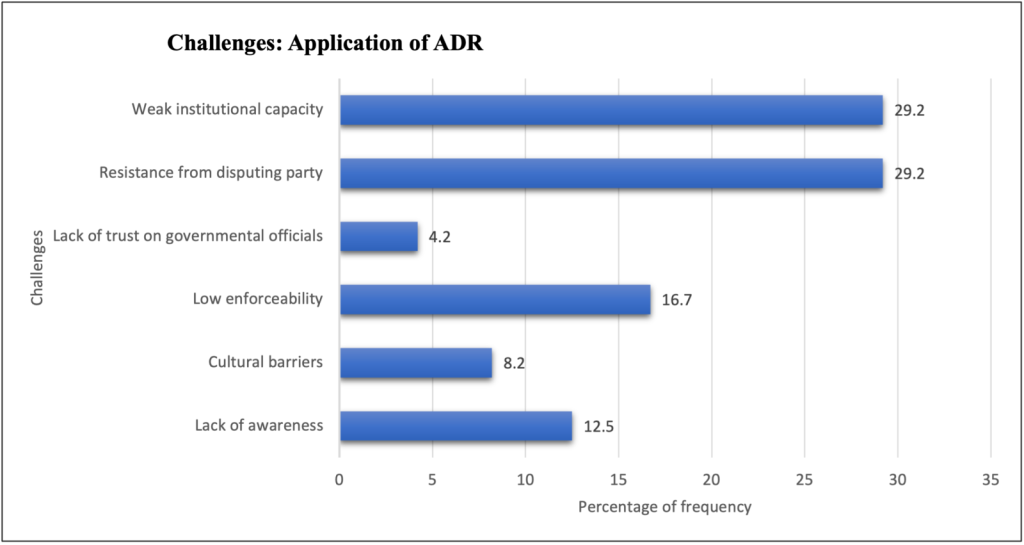

The key challenges in ADR application are summarised in Figure 11, with weak institutional capacity and resistance from disputing parties being the most significant issues, each cited by 29.2% of respondents. Other barriers include low enforceability of agreements, lack of awareness, cultural barriers, and distrust of government officials.

Figure 11: Challenges encountered in the application of ADR

When compared to other studies in Africa, similar challenges in land dispute resolution have been observed (Juma, 2021a; Kweka, 2023). In countries like Kenya and Uganda, boundary demarcation issues caused by environmental changes also contribute to land conflicts. Studies across Sub-Saharan Africa recognise ADR as a potential tool for resolving land disputes but highlight similar obstacles, such as weak institutional support and political interference.

The findings of this study align with these broader observations, suggesting that while ADR has potential, systemic changes are required to fully realise its effectiveness in addressing land conflicts in Ifakara and other regions of Africa.

This figure presents the major challenges in implementing ADR, emphasising the need for stronger institutional support and mechanisms for enforcement.

7. Conclusion

This study provides critical insights into the potential and limitations of ADR mechanisms, particularly mediation, in addressing inter-village land disputes in Ifakara, Tanzania. The persistent nature of these disputes underscores the urgent need for effective resolution methods that go beyond conventional litigation, and ADR offers a promising path in this regard. However, the relevance of these findings extends beyond the specific context of Ifakara and speaks to broader challenges in land governance and conflict resolution in Tanzania and other similar countries.

While ADR mechanisms hold promise, their success depends on addressing systemic challenges such as weak institutional capacity, low enforceability of agreements, and insufficient community awareness. Simply deploying ADR without tackling these foundational problems will result in limited success. The practical implications of these findings suggest that strengthening institutional frameworks, providing adequate resources, and enhancing local capacity for ADR are necessary steps for fostering sustainable conflict resolution. These systemic improvements would not only benefit Ifakara but also other regions across Sub-Saharan Africa facing similar land conflicts.

More importantly, this study highlights that community engagement is key to the success of ADR. Villagers’ active participation, facilitated through education and awareness of land laws and ADR processes, is essential for cultivating trust and ensuring culturally sensitive and inclusive dispute resolution. In this light, ADR mechanisms are not mere legal tools but instruments for social cohesion, fostering long-term peace and stability in communities grappling with land-related conflicts.

Additionally, the study points to a gap in existing monitoring systems, which has allowed many disputes to resurface even after ADR agreements are reached. Addressing this issue is not merely a technical challenge but a crucial step towards ensuring the longevity and enforceability of mediated settlements. Without a reliable system for tracking compliance, the benefits of ADR will remain limited and short-lived.

Ultimately, the significance of this research lies in its potential to inform policymakers, land administrators, and communities about the complexities of inter-village land disputes and the practical steps needed to enhance ADR mechanisms. By identifying and addressing the barriers to effective mediation – whether through institutional strengthening, improved boundary demarcation, or enhanced stakeholder engagement – ADR can play a transformative role in resolving land conflicts. For towns like Ifakara, the adoption of these recommendations could lead to more stable and equitable land governance, thus contributing to broader goals of peace and development in Tanzania and beyond.

To improve the effectiveness of ADR mechanisms, the study recommends the following:

- Strengthening institutional capacity by providing adequate training for mediators and equipping the land department with modern surveying tools.

- Improving stakeholder engagement to build trust in the ADR process. This can be achieved through awareness campaigns that educate villagers on land laws and ADR procedures.

- Updating boundary demarcations using advanced surveying techniques, such as GIS, and involving local communities in the process to ensure acceptance of the boundaries.

- Establishing mechanisms for monitoring and enforcing ADR agreements, including formal legal recognition of mediated settlements to prevent recurring disputes.

Reference List

Ampeire, A. (2017) Alternative dispute resolution: mediation, conciliation, arbitration. Kampala, Fountain Publishers.

Anyanwu, C. and Aluko, M. (2022) ADR in property disputes: a comparative study. Journal of Comparative Law, 45 (2), pp. 112–136.

Avery, K. (2013) Land conflicts and justice: a political theory of justice. 3rd ed. New York, Cambridge University Press.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), pp. 77–101.

Bruce, J.W. and Boudreaux, K. (2013) Land tenure and resource management in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC, World Bank.

Bryman, A. (2016) Social research methods. 5th ed. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Buscagila, E. and Stephan, P. (2012) An empirical assessment of the impact of formal versus informal dispute resolution on poverty: a governance-based approach. International Review of Law and Economics, 25 (1), pp. 89–106.

Bush, R.A.B. and Folger, J.P. (1994) The promise of mediation: responding to conflict through empowerment and recognition. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Byrne, D. (1999) Social exclusion. Buckingham, Open University Press.

Chitkara, P. (2023) Challenges in ADR implementation in South Asia. South Asian Legal Review, 39 (1), pp. 57–74.

Conteh, M. and Yeshanew, S.A. (2016) Conflict and land management in Africa. Addis Ababa, African Union.

Creswell, J.W. (2014) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Los Angeles, SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J.W. and Plano Clark, V.L. (2018) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, SAGE Publications.

De Haan, A. (1999) Social exclusion: towards a holistic understanding of deprivation. London, Department for International Development.

Emanuel, P.N. and Ndimbwa, T. (2013) Land disputes and conflict resolution in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, Mkuki na Nyota Publishers.

Field, A. (2018) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th ed. Newbury Park, SAGE Publications.

Fischer, G. (2007) Beyond the food crisis: conflict and resource scarcity in the 21st century. In: Anderson, M. ed. Food security and sustainability in the developing world. Cambridge, Polity Press. pp. 45–67.

Fisher, R., Ury, W.L. and Patton, B. (2011) Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in. 2nd ed. New York, Penguin Books.

Friedman, M. (2018) The morality of capitalism: a political economy perspective on John Rawls’ theory of justice. Journal of Business Ethics, 149 (3), pp. 725–738.

García, R. (2021) ADR and land conflicts in Latin America. Latin American Journal of Legal Studies, 12 (3), pp. 204–226.

Giddens, A., Duneier, M., Appelbaum, R.P. and Carr, D. (2017) Introduction to sociology. 10th ed. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Haberl, H. (2015) The global resource use and socio-economic development. London, Springer.

Harsanyi, J.C. (2018) Cardinal utility in welfare economics and in the theory of risk-taking. Journal of Economic Theory, 171, 15–23.

Hassall, G. (2005) Alternative dispute resolution in Pacific Island Countries. Journal of South Pacific Law, 9 (2).

Home, R. (2020) Land, law and dispute resolution in Sub-Saharan Africa. London, Routledge.

Homer-Dixon, T.F. (1994) Environmental scarcities and violent conflict: evidence from cases. International Security, 19 (1), pp. 5–40.

Ibrahim, A.S., Abubakari, M., Akanbang, B.A. and Kepe, T. (2022) Resolving land conflicts through alternative dispute resolution: exploring the motivations and challenges in Ghana. Land Use Policy, 120, p. 106272.

Israel, M. and Hay, I. (2006) Research ethics for social scientists: between ethical conduct and regulatory compliance. London, SAGE Publications.

Juma, A. (2021a) Institutional weaknesses in ADR mechanisms in East Africa. African Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution, 16 (4), pp. 99–121.

Juma, W. (2021b) Barriers to effective ADR in land disputes: a Kenyan perspective. African Journal of Legal Studies, 13 (4), pp. 301–319.

Kairuki, J. and Ddaaki, M. (2021) Traditional dispute resolution and land tenure security in Uganda. Kampala, Makerere University Press.

Kalabamu, F.T. (2021) Land conflicts and alternative dispute resolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Botswana. In Zever, S.Z. ed. Land issues for urban governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Switzerland, Oxford University Press. pp. 171–187.

Kamau, W. (2009) ‘Law, culture and dispute resolution: prospects for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in Africa’, East African Journal of Peace and Human Rights, 15(2), pp. 336–360.

Kansiime, N. (2019) Promoting traditional ways of handling land disputes in Western Uganda. American Research Journal and Social Sciences, 8 (2), pp. 17–25.

Kishenyi, J. (2017) Legal and regulatory framework for land dispute resolution in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, Law Africa Publishing.

Kvale, S. (2007) Doing interviews. Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications.

Kweka, J. (2023) Legal reforms and the promotion of ADR in Tanzania. Tanzania Law Review, 12 (1), pp. 65–79.

Lamin, A. (2018) Inter-village conflicts and land disputes in rural Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, University of Dar es Salaam Press.

Lenoir, R. (1974) Les exclus: un français sur dix. Paris, Seuil.

Levitas, R. (1998) The inclusive society? social exclusion and new labour. London, Macmillan.

Lierk, M. (2018) Corruption and accountability at grassroots level: an experiment on the preferences and incentives of village leaders. Hamburg, German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

Lwanga, J. (2018) Community-based mediation and land disputes in Uganda: a case study of rural districts. Kampala, Fountain Publishers.

Madulu, S. Sagamaganga, Personal communication, 30 May 2024.

Magoha, R. Sagamaganga, Personal communication. 30 May 2024.

Maina, J. and Gathumbi, E. (2022) Community resistance to ADR in rural Kenya. Kenya Journal of Social Justice, 8 (3), pp. 34–57.

Makalanga, M. Sole, Telephone interview. 2 June 2024.

Malika, Z. Ifakara town council, personal communication. 29 May 2024.

Maro, F. (2022) ADR mechanisms in Tanzania: a critical assessment. East African Journal of Law, 14 (1), pp. 77–101.

Mbele, A. Ifakara, Personal communication, 29 May 2024.

Mbonde, F.J. (2015) Assessment of land use conflicts in Tanzania: a case study of Songambele and Mkoka Villages in Kongwa District. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Mzumbe University.

Mensah, A. (2023) Community engagement and institutional support in ADR: lessons from Ghana. African Journal of Dispute Resolution, 19 (1), pp. 27–42.

Merriam, S.B. and Tisdell, E.J. (2015) Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. 4th ed. San Francisco, John Wiley & Sons.

Moore, C.W. (2014) The mediation process: practical strategies for resolving conflict. 4th ed. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Moyo, S. and Chambati, W. (2023) Land disputes and inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Review of Economics and Finance, 15 (2), pp. 45–67.

Mmanda, M. Ifakara town council, Personal communication. 31 May 2024.

Mtengeti, S. and Mwambene, L. (2022) Colonial land policies and contemporary conflicts in Tanzania. African Land Journal, 18 (3), pp. 301–319.

Mtui, M. (2023) Persistent land disputes in Tanzania: the role of ADR. Journal of Tanzanian Studies, 22 (1), pp. 119–144.

Mulyungi, K. and Mwende, E. (2022) Gender and ADR: enhancing women’s participation in land dispute resolution in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lusaka, Southern African Legal Institute.

Mushi, G. and Kamugisha, A. (2023) Institutional capacity and the effectiveness of ADR in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, Tanzanian Legal Perspectives.

Mwakaje, G. (2022) Implementation challenges of land laws in Tanzania: a rural perspective. Rural Development Review, 29 (1), pp. 76–89.

Nakayiza, R. (2019) Historical land grievances and tenure security in Uganda: the role of community-based mediation. Journal of African Studies, 12 (3), pp. 45–60.

Ndangiza, P. and Turyamuhweza, R. (2020) Mediation as a tool for resolving land tenure disputes in Uganda. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 15 (2), pp. 102–121.

Nkonya, E., Mirzabaev, A. and Von Braun, J. eds. (2022) Economics of land degradation and improvement – a global assessment for sustainable development. Cham, Springer.

Noy, C. (2008) Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), pp. 327–344. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701401305> .

Ntuli, N. (2018) Africa: alternative dispute resolution in a comparative perspective. Conflict Studies Quarterly, 36–61.

Omondi, M. and Ochieng, P. (2022) Traditional leadership and land dispute resolution: the role of ADR in Kenya’s post-election conflicts. Nairobi, Kenya Studies Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Patton, M.Q. (2015) Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications.

Peters, P. (2021) Land, conflict, and identity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Studies, 45 (2), pp. 235–256.

Rashid, M. and Rahman, M. (2023) ADR practices in Bangladesh: lessons and challenges. Bangladesh Law Review, 27 (2), pp. 145–168.

Rawls, J. (1971) A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Redfern, A. and Hunter, M. (2021). Law and practice of international commercial arbitration. 6th ed.UK Sweet & Maxwell.

Richards, A.I. (1939). Land, labour, and diet in Northern Rhodesia: An economic study of the Bemba tribe. London: Oxford University Press.

Ringo, A. (2023) The role of local institutions in land dispute resolution in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam University Press.

Rubakula, G., Wang, X. and Wei, J. (2019) Land disputes in rural Tanzania: a case study of Ifakara Town Council. Beijing, China Agricultural University Press.

Saruni, K., Urassa, J. and Kajembe, G. (2018) Population pressure, environmental degradation, and land conflicts in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam, Mkuki na Nyota Publishers.

Schomerus, M. and Rigterink, A.S. (2021) Disputes and displacement: a critical review of land conflicts in Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 58 (4), pp. 501–515.

Shemdoe, R. and Kihamba, C. (2023) The political economy of land disputes in Tanzania. Journal of Development Studies, 19 (3), pp. 67–88.

Silver, H. (1994) Social exclusion and social solidarity: three paradigms. International Labour Review, 133 (5–6), pp. 531–578.

Singh, T. and Mbatha, M. (2022) Land reform and ADR in South Africa. South African Law Journal, 139 (2), pp. 195–220.

Tanzania National Bureau of statistics. (2022) Population and housing census: age and sex distribution report. National Bureau of Statistics, Tanzania.

Tejada, J.J. and Punzalan, J.R. (2012) On the misuse of Slovin’s formula. The Philippine Statistician, 61 (1), pp. 129–136.

UN Women (2017) Seminar report – Gender-responsive alternative dispute resolution. Asia-Pacific: UN Women. Available at: <https://asiapacific.unwomen.org> (Accessed: 15 November 2024).

Verplanke, J. and McCall, M. (2010) Boundary demarcation and land conflicts: the role of participatory mapping in Tanzania. Enschede, University of Twente Press.

Wamala, D. (2020) Fostering peaceful coexistence through community-based land mediation in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda Land Trust.

Weber, M. (2019) Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology. Berkley, CA University of California Press.

Wehrmann, B. (2017) The dynamics of land tenure and conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. Berlin, German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Williams, K. (2023) The role of ADR in conflict resolution in emerging economies. Global Journal of Legal Studies, 31 (2), pp. 245–273.

Yin, R.K. (2014) Case study research: design and methods. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, SAGE Publications.