Abstract

This study is conceived within a theoretical framework that seeks to rationalise the linkages between space, peacebuilding and urban resilience. The paper responds to the research question: How do city residents build urban resilience and prevent violent conflict? The study obtained primary data by fusing both qualitative and quantitative research methods through household data collection and the Geographic Information System (GIS). The study notes indigenous conflict management, the traditional justice system and community policing, civic education, non-governmental interventions, and political and economic measures as factors of urban resilience to violent conflict. The study concludes that collaboration becomes effective when initiatives are designed at the community level with ties to specific government agencies for additional support, expertise and an enabling environment.

Keywords: Conflict, violence, resilience, peacebuilding, Jos

1. Introduction

The city of Jos in Nigeria’s North Central zone has experienced episodic outbreaks of violent conflict along sectarian and ethnic lines in various communities during the past three decades. The years 2001, 2004, 2008, 2010 and 2011 were all characterised by far-reaching violence that pitched opposing communities of Hausa-Fulani descent (mainly Muslim) against the aboriginal ethnic groups, notably Berom, Afizere and Anaguta (principally Christian). The perennial crisis is often rooted in indigene/settlers’ disagreement, access to political power and political representation (Kwaja, 2014). The researcher selected Jos as a site of investigation for this study to examine to what extent peacebuilding approaches among urban residents have helped to build and strengthen resilience to violent conflict in a fragile city.

The World Bank (2011a, 2011b) posits that the most viable solution to preventing violent conflict lies in understanding and supporting community resilience. In line with this assertion, cities are integral as sites of urban conflict. A vision for cities has never been more important than it is today. This becomes pivotal as the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 aims at making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. This article is conceived within a theoretical framework that seeks to rationalise the linkages between space, peacebuilding and urban resilience. Although urban perspectives on peacebuilding do not offer a unified approach, they involve a range of interdisciplinary viewpoints. While the literature on urban peacebuilding often centres on high-profile global cities (ICRC, 2017), this research brings attention to the unique challenges and strategies within African cities, where informal community networks play a pivotal role. Additionally, insights from Jos can inform policy on fostering resilience and sustainable peace in other urban areas with similar sociopolitical landscapes. The research seeks to:

- Identify the root causes and triggers of violent conflict in Jos.

- Evaluate the roles of various stakeholders in urban peacebuilding efforts.

- Assess the effectiveness of existing peacebuilding strategies towards resilience.

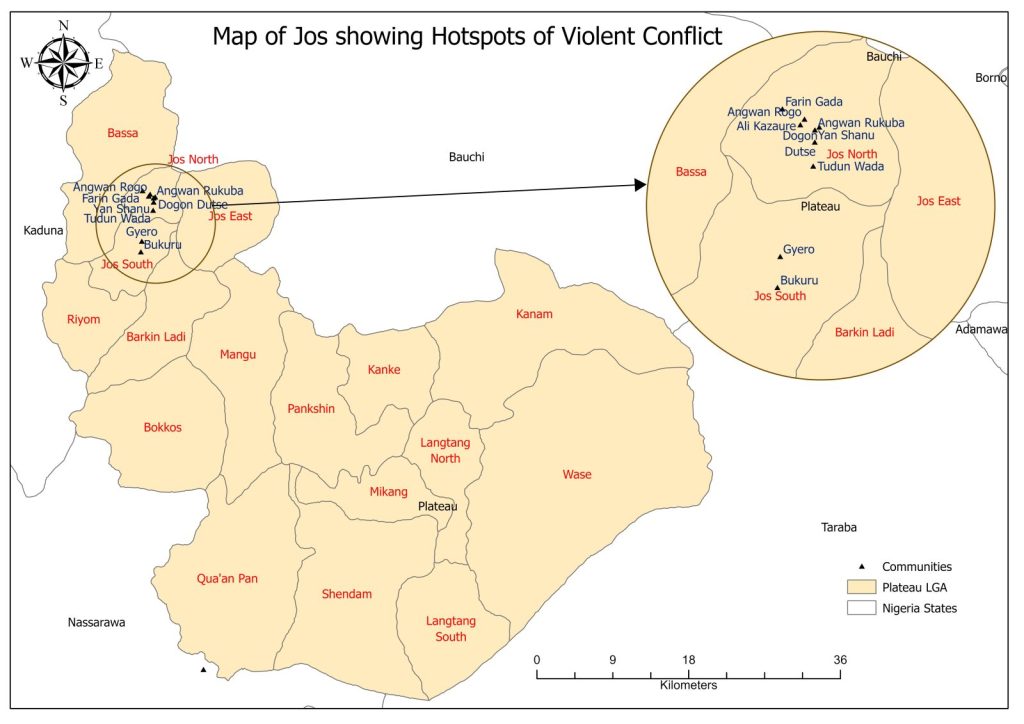

The map of Jos (see Figure 1) highlights communities that have historically experienced violent conflict due to underlying ethno-religious, sociopolitical and economic tensions. According to a non-attributable comment from a youth leader and indigene of Jos in Abuja on 19 August 2022(b), these conflicts often erupt in specific neighbourhoods where demographic diversity intersects with high-stakes competition for resources, historical grievances and political power struggles. Notable areas include: Angwan Rukuba, Dogon Dutse, Tudun Wada Yan Shanu, Ali Kazaure and Farin Gada. Others are: Bukuru Gyero, Nassarawa and Angwan Rogo. The map serves as a visual tool to understand the spatial dimensions of conflict in Jos. Highlighting these conflict-prone areas can aid peacebuilders, policymakers and researchers in crafting targeted interventions that consider the unique dynamics of each neighbourhood, fostering lasting peace through localised understanding and tailored conflict resolution strategies.

Figure 1: Map of Jos

2. Methodology

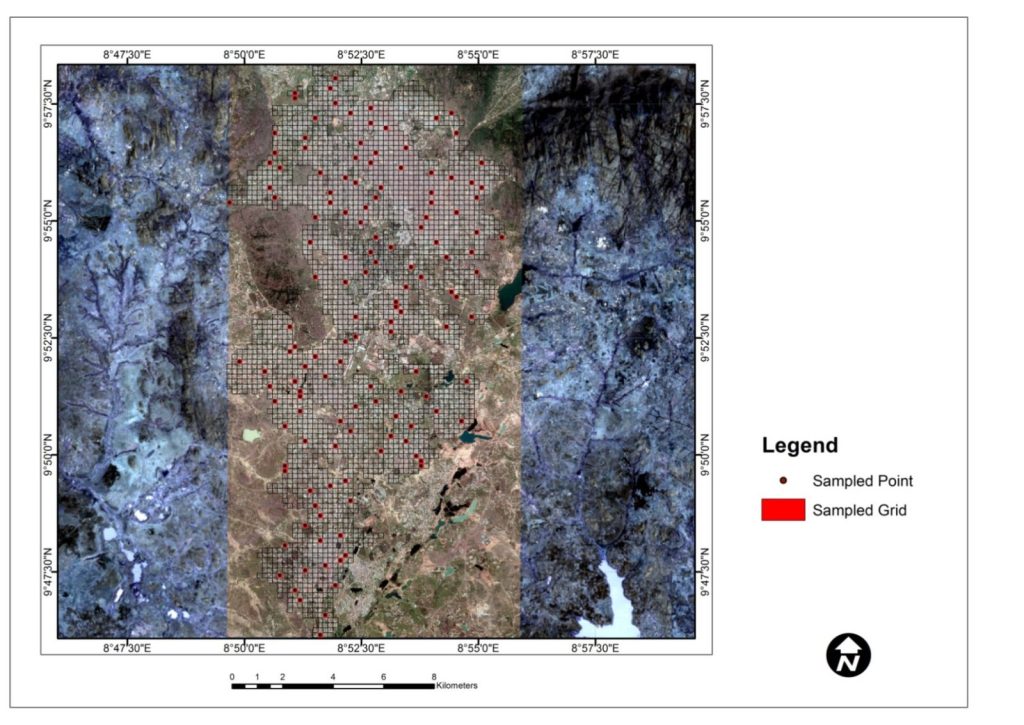

The researcher obtained primary data from residents through questionnaire administration and in-depth interviews and used gridded population data and the Geographic Information System (GIS) in selecting household clusters. The grid intervals covering the built-up areas of Jos were generated through remote sensing. Automated grid intersections at 200×200 metres were generated to select the sample size in the city. Using this procedure, the researcher identified 2 772 grids. The number of residential buildings identified within the grids were 9 552. Subsequently, 2% of the buildings were sampled, where 198 respondents were interviewed. Selecting 2% of the buildings in the study area as a sample for interviewing 198 respondents provided a manageable yet representative subset of the total population, enabling detailed analysis while maintaining logistical feasibility. The geographic coordinate locations of the points and grids (longitude and latitude) generated are shown on Figure 2. This study bridges a theoretical gap in data collection by fusing both qualitative and quantitative research methodology through household data collection and GIS. Through small-area segmentation techniques, this novel approach offers a distinct opportunity to combine multiple sampling procedures that help to address problems occasioned by the lack of census data for large-scale study in developing countries.

Table 1: Sampling distribution within the study area

| S/n | City | Number of grids | Number of selected grids | Number of residential buildings in the grids | Buildings where respondents were selected |

| 1 | Jos | 2 772 | 275 (10%) | 9 452 | 198 (2%) |

Source: Author’s Field Survey (2020)

Figure 2: Grids of residential buildings in Jos

Data collection for this study faced several limitations, including biases in self-reported data and logistical challenges. Triangulation with multiple data sources, such as government reports, non-governmental organisation (NGO) records and community group insights helped to validate self-reported data and reduced bias. Additionally, the research assistants engaged trusted local intermediaries to access restricted areas safely and translated information accurately, ensuring diverse representation. By incorporating these approaches, the study enhances data reliability and builds a more comprehensive understanding of resilience dynamics in conflict-affected urban settings.

The data collected between 2020 and 2022 retains significant relevance in 2024, as the themes and findings of the study continue to resonate. This enduring relevance is attributed to the protracted nature of violent conflict and peacebuilding processes. The insights gained from the data illuminate structural challenges, underlying causes, and ongoing peacebuilding initiatives that influence the socio-political environment in Jos today. Furthermore, the data offers a valuable retrospective lens through which to assess the effectiveness of interventions and the evolution of conflict and peacebuilding efforts over time. Such analysis is essential for informing policymakers, civil society, and stakeholders about lessons learned and existing gaps. Current developments in Jos and across Nigeria reveal that many issues identified in 2022, including land use conflicts, ethno-religious strife, and government intervention, continue to manifest in various ways. This underscores the necessity of addressing these persistent challenges. In terms of contextual significance, the findings can serve as a reference point for evaluating any substantial progress made since the data collection period, potentially guiding further research to explore changes and their underlying causes. Consequently, the findings of this paper represent a vital contribution to the ongoing discourse surrounding peacebuilding and conflict resolution in Nigeria.

2.1 Data collection and operationalisation of community resilience

The unit of analysis on which survey data is collected is an important thrust for the discussion of methodology in practice (Brück et al., 2009). The household is at the lowest level of analysis in this study. The research survey involved two levels. At the first stage of the quantitative field work, the researcher obtained data on various measures and peacebuilding efforts aimed at addressing violent conflict in the city. Therefore, respondents were asked to rate the effectiveness of five parameters identified as the critical building blocks of resilience in five domains. These are: informal violence prevention and conflict management methods, economic and social development, political development and governance, justice and security, communication and education. These are further divided into 37 subjective indicators through which resilience has been measured over the years in past studies (Marshall et al., 2010; Nguyen and James, 2013). These were measured on a five-point Likert scale – 1 = very ineffective, 2 = ineffective, 3 = neutral, 4 = effective and 5 = very effective. For ease of operationalisation, the researcher transformed the data from Likert scale into categorical predictors. The community resilience indicators were transformed by grouping them into categories and values to generate a mean (Σ) for each of the cases. Fundamental reasons for variable transformation include reducing skewness, equal spreads, linear and additive relationships (Emerson and Stoto, 1983). For the purpose of this study, the 37 variables constituting community resilience measures were recoded into a single variable with Cronbach’s alpha test to determine their reliability. This step yielded .934 and satisfied the normality of their distributions test.

The researcher analysed the data through confirmatory factor analysis, which is a statistical modelling method that assesses how accurately different systems measure and evaluate a concept. Bartlett’s test of sphericity is crucial for determining the suitability of factor analysis for the dataset in the study. A significant Bartlett’s test (typically with a p-value < 0.05) indicates that the variables in the dataset are sufficiently correlated to justify the application of factor analysis. Subsequently, the variables of interest were extrapolated from the factor analysis results and subjected to qualitative fieldwork through key informant interviews with respondents drawn from religious communities, women’s groups, youths, community development professionals and the media.

3. Urban spaces, resilience and bargaining theory of conflict

Urban perspectives on peacebuilding do not offer a unified approach; they involve a range of interdisciplinary perspectives. In this context, Ljungkvist and Jarstad (2021) affirm two broad orientations in the study of urban dimensions of peacebuilding. The first focuses on urban peacebuilding responses, and the second on how urban environments condition peacebuilding efforts. Both of these orientations clearly draw on theoretical insights from the field of urban studies. This article aligns closely with the former, as it focuses on the preconditions necessary for peacebuilding through the bottom-up approach and close partnership with the state agencies in Jos. Thus, paying attention to how peacebuilding initiatives interact with complex social, political, economic and cultural dynamics of urban environments, as well as with materiality of the city, becomes critical (Björkdahl, 2013). Drawing from this line of thought, a central argument is that the city represents an agglomeration of ideas, as well as social and psychological infrastructure of urban resilience.

For the purpose of conceptual clarification, this study draws on foundational studies by Chandler (2012) and Bourbeau (2013). Resilience is defined as the capacity to positively or successfully adapt to external problems or threats (Chandler, 2012). A broader definition presents resilience as the process of patterned adjustments adopted by a society or an individual in the face of endogenous or exogenous shocks (Bourbeau, 2013). The key point highlighted in these studies is that resilience is increasingly focused on the capabilities, processes, practices, measures, approaches and collective efforts. Opportunities do exist to harness the transformative potential of cities to promote development, implement effective resilience systems, and reduce violent conflict and its consequences. A vision for cities has never been more important than it is today. SDG 11 implores us: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.” Success in achieving the targets under SDG 11 sets the stage for achieving targets in many of the other SDGs.

Kaldor and Sassen (2020) analysed certain urban capabilities and mutuality that underpin densely populated urban conurbations and are needed to govern everyday negotiation for peace in a heterogenous urban enclave. Such capabilities, they argue, inherently provide a counter, however slight, to forcible fragmentation and closure and to the dynamic of violent conflict. A central argument in the article is that recognising such urban capabilities – even where we least expect them to be present – is one key to understanding cities facing profound violent conflict. One important implication is a better understanding of how city residents can maximise whatever pertinent and collective capabilities are embedded in an urban space as a socio-cultural infrastructure of peace. The concept of urban capabilities is well situated in relation to the bargaining theory of conflict and is employed in this article to explain how urban residents of diverse social groups navigate their way towards peaceful coexistence in a fragile city.

According to Lake (2010), the core idea of bargaining theory is that, because war is costly, there must exist a negotiated outcome that will leave both sides better off than if they engaged in fighting. The theory depicts two actors in dispute over an issue of fixed value. These could be land, natural resources or a political outcome. Thus, if the actors fight, each incurs some cost respectively calibrated relative to the value of the object or value in contention. As long as the costs of fighting are positive, the theory implies that a bargaining range must exist around the set of divisions of the issue that both sides prefer to contend over. Sticher and Vuković (2021) observe that warring parties engage in ceasefires in pursuit of a variety of objectives, some of which reduce while others fuel violent conflict. They present three distinct bargaining contexts for violent conflict. In the ‘diminishing opponent’ context, actors believe that a war confrontation with the deployment of arms and ammunitions yields a better outcome than a political truce negotiation for peace. In the ‘forcing concessions’context, parties recognise the benefit of conflict settlement, but expectations about a mutually acceptable agreement are divergent. Lastly, in the ‘enabling agreement’ context, expectations converge, and actors seek to pursue settlement without incurring further costs. Therefore, conflict party leaders adapt their strategic goal, from envisaging a military advantage, to boosting their bargaining power, to increasing the chances of a negotiated settlement. They may use a ceasefire in the pursuit of any of these three goals, shifting the function of a ceasefire as they gain a better understanding of bargaining dynamics.

The aforementioned studies focused on conventional armed conflict in which warring factions include separatist groups, rebels and state military. However, scholarly attention on communal war in which various militia formations engage in violent conflict have only begun to gain traction recently to improve our understanding of local violence, (non-)escalation and implications for prevention. Therefore, by conceptualising this research on violent conflict and resilient urban spaces, the study seeks to contribute to the understanding of resilient approaches as veritable tools in negotiating and sustaining everyday peacebuilding in a deeply divided society.

Applying bargaining theory to the context of Jos, offers valuable insights into the persistent cycles of conflict and efforts towards peace in this urban environment. Bargaining theory, which traditionally examines how actors negotiate and reach agreements under conditions of conflicting interests, is particularly relevant in Jos, where ethno-religious divisions, political competition and economic pressures create an environment ripe for both conflict and potential cooperation. In Jos, bargaining theory could help explain why peace agreements or truces between conflicting groups – often brokered by local leaders, community elders or government officials – tend to be fragile. In such a context, groups may enter negotiations not only to resolve differences but to gain temporary strategic advantage, secure resources or gain political capital. This can result in ‘bargains’ that are, in practice, tenuous and lack genuine commitment from all sides. Therefore, successful peacebuilding in Jos may require balancing power dynamics by ensuring that all groups, including those historically marginalised, have a voice in negotiations. In sum, bargaining theory provides a framework for understanding why peace initiatives in Jos have struggled and offers guidance on strategies that could improve future peacebuilding efforts. By addressing issues of trust, credible commitment, information asymmetry and power imbalances, peacebuilders can foster more sustainable agreements and advance a model of urban peacebuilding tailored to the unique complexities of Jos. To assess the validity of this framework, the next section highlights the significance of this city as a site of interest.

4. Causes of violent conflict in Jos

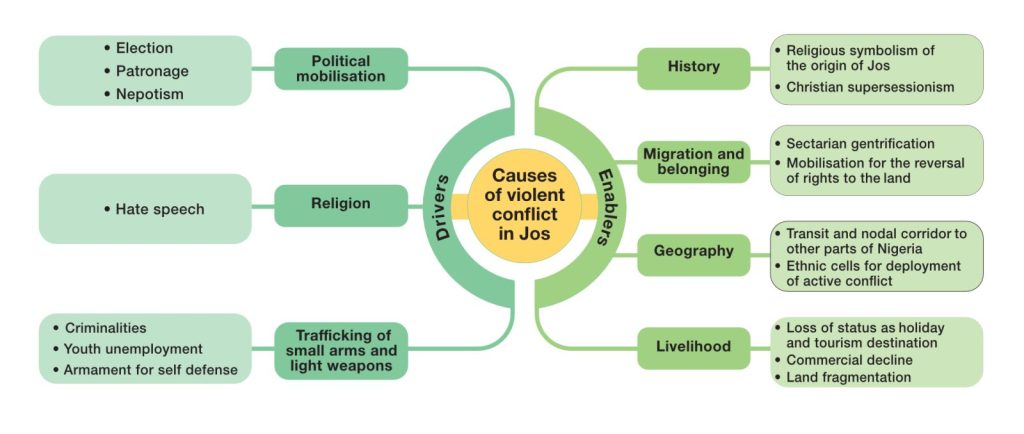

The causes of violent conflict are divided into enablers and drivers. Jos is susceptible to violent conflict as a result of a combination of mutually reinforcing factors, which are history, geography, livelihood, migration and belonging (Key informant interview, 2022b). These are considered primary enablers of violent conflict in the city. On the other hand, three essential factors serve as drivers of violent conflict – religion, political mobilisation and the proliferation of small arms and light weapons.

4.1 History

During the colonial period and under the defunct northern Nigeria region, Jos (as a city and administrative capital) was regarded as a Christian domain, as opposed to surrounding cities such as Bauchi. Although this perception was never accurate at any point, according local residents, it imposed a Christian identity on the city and surrounding areas that now constitute Plateau State. Through oral history, many residents (mostly Christians) claimed that Jos meant “Jesus Our Saviour” (Key informant interview, 2022b). This has its origin in the renaming of the city of Gwosh to Jos in 1904, and it is attributed to a German missionary, Dr. Herman Wilhelm, of the Sudan United Mission (SUM). The change of name was necessary to fit the Christological acronym, ‘Jesus Our Saviour’. Thus, SUM established a narrative among the natives that rendered Jos, ‘as a Christian city and the New Jerusalem of Africa’. This account projects Jos as the bastion of Christianity in northern Nigeria and the fulcrum of its evangelisation activities (Ahiaba, 2016:104). As the city descended deeper into violent conflict some decades ago, this sectarian labelling has become a catch-all explanation for the city’s communal warfare, particularly among the Christians and Muslims considered indigenes and settlers respectively. Since 1999, attempts to assert the diversity of the town are often regarded as the struggle to take over or downplay the Jesus narrative about the origin of the city with fierce contestation.

4.2 Migration and belonging

Related to the point on history, the acclaimed settlers of Jos had for a long time held the belief that all who migrate to the city can automatically lay claim to a sense of belonging. This is why the notion of Tudun Wada and Sabon Gari (places in northern Nigerian cities where outsiders live) do not apply in Jos. The city is permanently gentrified particularly along sectarian divides. The realisation in recent times that a Kano indigene who settled in Jos 20 years ago has superior rights over a Jos indigene who settled in Kano for about the same period has led to the campaign for a reversal of rights. Thus, there are complaints that Muslims can build mosques of various sizes and numbers in Jos, while in other Muslim-dominated cities in northern Nigeria, Christians are permitted to build their churches only on a designated portion of land allocated to them by local authorities.

4.3 Geography

Jos is located next to Bauchi. Generally, there is a southward migration across Nigeria. It is also a major connecting point for travellers, providing linkages to the north east. Each ethnic group across the country desires a base in Jos, which has led to the clamour for small ethnic enclaves across the city. These become cells ready for deployment in active conflict.

4.4 Livelihood

Jos has lost its status as a prominent holiday and tourism destination. Resultantly, the local economy is affected adversely, and its reliance on the city (as an urban organism) to feed its population is becoming difficult. The city’s main market was destroyed by fire, and the business zone housing the terminus is no longer the regional trade hub it used to be. Consequently, most urban residents were forced to return to the land, which they plough or sell to make ends meet. To justify their access to land, some extortionists revert to claims of autochthony and argue that they have been in the city from time immemorial, forgetting that in the 1970s, vast swathes of lands were sold to ‘settlers’ with undocumented agreements.

4.5 Political mobilisation

The awareness of ‘who owns Jos’ is a central question mainly for electioneering purposes. This is why the spike in the violence coincided with the return to democratic rule in 1999. Drawing from these historical accounts, these communities became suspicious of each other during political events such as elections. All elections and political appointments since the creation of Jos North Local Government Area in 1991, have become synonymous with severe competition, tension and potential conflict. In this regard, one respondent said, “If we stop voting, we will likely stop fighting too”. This allegory summarises the role of politics and access to political power through contestation and mobilisation of voters among the competing groups in electing someone from their ethnic and religious group into political office. This is seen as symbolic of political domination and not just representation, particularly for patronage.

4.6 Religion

There is a subtle politicisation of religion in Jos, which often widens the fault lines of conflict. However, beyond the politics, Christians and Muslims express much animosity towards each other, with each religious group keen to assert its claimed superiority. Ultimately, worship is rarely a spiritual engagement but rather a cynical ‘show of force’ intended to establish domination and demonstrate to adherents of other religious persuasions their professed right to ownership and control of the city.

4.7 Trafficking of small arms and light weapons

The illegal movement of guns and local fabrication of small arms both within Plateau State and across Nigeria contribute to the conflict profile. Indeed, trafficked firearms are a major driver of violent conflict in the city. For instance, in April 2022, over 500 small arms and light weapons were recovered in Plateau State by a military formation code named “Operation Safe Haven” (Channels TV, 2022). Recently, the operatives of the Force Intelligence Bureau also recovered 57 AK47 rifles and a large supply of ammunition in Jos. Three of the suspects were between the ages of 20 and 25 years. This lends evidence to the rising incidence of crime among the economically disadvantaged youths in the city (Ayitogo, 2022). Generally, the proliferation of firearms can be understood against the backdrop of widespread criminality and the need for self-defence among various warring communities in Jos and Plateau State at large. Since conflict broke out in Plateau State about two decades ago, communities and individuals, especially those living in the hinterlands, have felt the need to arm and defend themselves and their properties against violent extremists, religious and ethnic militias, unknown gunmen, suspected Fulani herdsmen, cattle rustlers and bandits. This self-defence against known and perceived enemies has made Plateau State one of the notorious hubs for small, light and heavy weapons (Sadiq, 2016). In spite of the presence of the enabling factors and drivers of violent conflict in the city, some urban residents devise strategies for peaceful coexistence, even in their fragile context. The next section considers the factors influencing urban resilience to violent conflict in Jos.

Figure 3: Causal model of violent conflict

In the conceptual model on the causes of violent conflict in Jos, enablers and drivers interact in complex ways, creating a web of conditions that escalate tensions and trigger violence. Enablers like history, migration and belonging, geography, and livelihood form the underlying context that makes the city susceptible to conflict. The historical legacy of disputes over land and political control has shaped community identities and territorial claims, reinforcing divisions along ethnic and religious lines. Patterns of migration and contested belonging exacerbate perceptions of exclusion, where certain groups feel marginalised or threatened by the presence of others, especially around questions of who qualifies as an ‘indigene’ with legitimate land and resource rights. Drivers – political mobilisation, religion and trafficking of small arms and light weapons – actively ignite and sustain violent conflict by exploiting these underlying tensions. Political leaders often mobilise communities along ethnic and religious lines to secure support, aggravating identity-based divisions and feeding hostility between groups. Religion, while culturally significant, becomes a divisive tool, as leaders use it to rally groups against perceived enemies, deepening distrust and feeding sectarian narratives. The availability of small arms and light weapons facilitates the escalation of confrontations, as access to weaponry allows disputes to turn deadly and intensifies cycles of revenge and retaliation. Together, enablers create the landscape of underlying vulnerabilities, while drivers transform these vulnerabilities into active conflict, with each variable reinforcing the other in a cycle of instability and violence in Jos.

5. Factors influencing community resilience responses to violent conflict

The study employed factor analysis to identify the determinants of community resilience to violent conflict in the study area. Factor analysis is a variable reduction approach. In carrying out factor analysis, Tabachnick and Fidell (2001) posit that variables with loadings 0.32 and above may be interpreted. An earlier study by Stevens (1992) recommends interpreting only factor loadings with an absolute value greater than 0.4 (which explains around 16% of variance). This study therefore used 0.50 as cut-off points, which is considered to be good, as it has 25% overlapping variance. This test (overlapping variance) indicates the amount of shared variance between pairs of variables. Factor loading less than 0.50 will be suppressed. The logic behind suppressing values less than 0.50 was based on Stevens’ (2002) suggestion that this cut-off point was appropriate for interpretative purposes (that is, loadings greater than 0.4 represent substantive values). The grouping of variables is based on factor loadings, which indicate the degree of association of a variable with the factor (Ofori and Chan, 2001). Therefore, a variable that appears to have the highest loading in one factor belongs to that factor. Trost and Oberlender (2003) suggest that the value of factor loading should be between 0.4 and 0.9.

The need to ascertain the extent of adequacy of the data loaded for the study informed the use of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test. For factor analysis to be adequate, Kaiser recommends that values greater than 0.5 are acceptable. Factor analysis does not attach labels to the factors generated, and the substantive meaning given to a factor is typically based on the examination of what the high loading variables measure (Kim and Mueller, 1978). A factor is named by examining the largest values linking the factor to the measured variables in the rotated factor matrix, and the final number of factors is based on the rotated solution that is interpretable (Green and Salkind, 2003). Hence, the factors influencing community resilience to violent conflict in Jos are discussed subsequently.

The factor analysis produced six factor groupings that accounted for 62.316% of the variance explained. As shown in Table 1, the KMO for Jos metropolis was 0.883, which was within the acceptable range. It is evident that factor analysis is appropriate for the data set. Similarly, Bartlett’s test of sphericity is highly significant (p = 0.000) and justifies the appropriateness of the factor analysis. The principal components analysis with Varimax rotation of the 38 identified variable factors influencing community resilience response to violent conflict in Jos produced six factor categories in Jos, which are labelled and described as presented in Table 2.

Table 2: KMO and Bartlett’s test of factors influencing community resilience to violent conflicts in Jos

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | .883 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 2038.360 |

| Df | 703 | |

| Sig. | .000 | |

Factor one (f1) – indigenous conflict management measures

These describe strategies community members in Jos devised over the years to build community resilience to violent conflict. These include mediation through a third-party intervention, negotiation, alternative dispute resolution, collaboration, arbitration and conciliation. According to Child (2006), the appropriate method may depend to a large extent on the nature and type of conflicts involved. Typical of traditional African societies, this article observes that Jos as a traditional city is occupied by residents who maintain institutional mechanisms as well as cultural sources to uphold the values of peace, tolerance, solidarity and respect for one another. These measures have been responsible for peace education, confidence-building, peacemaking, peacebuilding, conflict monitoring, conflict prevention, conflict management, and conflict resolution. At the helm of the system is seated the traditional institutions of justice and supported by chiefdoms from lesser chieftaincies and district heads across the city and the peri-urban neighbourhoods. Findings from an interview with a Christian youth leader and community development professional working with an international humanitarian and peacebuilding organisation based in Jos indicate that there are good examples of community efforts that have helped to shape urban peacebuilding in Jos over the years. The following extract provides an empirical example:

Dadin Kowa in Jos is a Muslim-majority district which has vowed never to participate in conflict. Although they could wipe out the Christians [community closely situated to them] in a day, they haven’t. … this is prevented through a strong network of youth groups who coordinate each other. This network [of youth] cooperate with the police on crime as well. Dadin Kowa is across the road from Zarmaganda (Christian majority) which is said to be uncoordinated, prone to crime and violence. This is particularly notable as it is urban and has the same unemployed youths … But somehow this has been peaceful. There are similar community initiatives around Gangare area as well (Non-attributable comments, 2022a).

The foregoing also alludes to the fact that decades of violent conflict among the warring communities have engendered urban segregation and divided the city along the Muslim north and the Christian south. Nevertheless, peacebuilding efforts by the external interlocutors (development partners) in partnership with the local communities are strengthening resilience (Madueke, 2019). Beyond their separate retreat to sectarian enclaves, the warring communities have found space to interact and bargain for peaceful coexistence in the city, at least for about a decade. For example, the conflict stability and security fund (CSSF) – a Women Peace and Security project is a consultative forum aimed at enhancing the capacity of women on issues that affect their participation in decision-making, atrocity prevention, community policing and peacebuilding processes. The initiative is being implemented by the Women and Girl-Child Rescue and Development Initiative (WGRDI) with the support of the Women for Women International. This initiative brought together women from two communities: Chwelnyap, popularly known as Congo-Russia in Jos North and Dadin Kowa in Jos South (Nanlong, 2023).

At the core of the indigenous conflict management methods are mediation, support through indigenous dispute resolution, community truth and reconciliation groups, inter-religious dialogues, non-violent campaigns by respected community leaders, iterated capacity-building on conflict monitoring and resolution and cultural exchanges. Traditional community leaders also address some conflict at a frozen state before they transform to violence in the city. In 2013, five communities comprised of Afizere, Anaguta, Berom, Fulani and Hausa reached widely respected agreements, negotiated by the Humanitarian Dialogue Centre. The agreement lists the issues that need to be discussed, the different opinions on each of these issues by each ethnic group, the relevant stakeholders to be included in each issue and a comprehensive time frame for addressing it (as well as activities to be conducted by the Humanitarian Dialogue Centre to assist efforts). There were 30 issues covering governance, crime, transitional justice, access, the indigeneship issue, demarcation of boundaries, employment, the market, cultural heritage and sanctions, among others (Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2013). In response to community resilience to violent conflict, all variables under factor one accounted for 13.09% of the varianceexplained. This is related to how the community members have responded to violent conflict over the years and it is labelled as ‘indigenous conflict management factors’.

Factor two (f2) – political measures

The study rests on the assumption that the political capital possessed by the residents of the community would influence how they experience and respond to the incidence of violent conflict within and around their domains. Political party engagement in peace initiatives in Jos has sometimes taken the form of supporting interfaith dialogue and working with state agencies to calm community tensions. This collaboration has aimed to reduce polarisation, which often emerges during election cycles, by establishing inclusive frameworks that promote collective decision-making on local security and development issues. However, such efforts have faced challenges, especially when communities perceive political actors as biased or as fuelling sectarian divides for electoral gain (Krause, 2011; Kew, 2021).

Communities with strong political capital and principles of inclusion and fairness are expected to fare better in the face of violent conflict, thereby enabling longer-term processes of transformation or recovery. This article argues that the central role of political factors in building community resilience to violent conflict is to transform communal relations towards a sociopolitical and economic system capable of fostering peaceful coexistence and ensuring a self-sustained peace. Such a transformation is beyond the scope of a formal governance system alone. Rather, the findings show that it requires more holistic and locally-relevant approaches that address a set of concerns, including awareness activities by political parties on peace and social cohesion, decentralisation of political power, promotion of human rights and power-sharing arrangements among various Indigenous groups in the city (Non-attributable comment, 2021a).

Others are activities of civil society organisations (CSOs) on peacebuilding, campaigns against political violence, interparty meetings on peaceful elections and participation of women and youth in decision-making. This article establishes that the political factor of community resilience to violent conflict in Jos is the inclusion of the minority groups in the political configuration of administrative power in the public service and balancing of political positions with fair representation of all the constituents. In response to community resilience to violent conflict, all variables under factor two accounted for 10.621% of the variance explained. This is related to how the community members have responded to violent conflict over the years and it is labelled as ‘political factors’.

Factor three (f3) – economic measures

As argued earlier in this article, a community that is resilient to violent conflict has economic opportunities for the residents. It has a diverse range of employment opportunities, income and informal business services. It is inhabited by the people who are resourceful and have the capacity to accept uncertainty and respond (proactively) to change. The study highlights and examines the array of economic factors of community resilience to violent conflict in Jos. In terms of economic assets that were identified by communities, the respondents placed the greatest emphasis on the importance of employment and income. For example, respondents indicated that the capacity of their communities within Jos to recover from the adverse effects of violent conflict and adapt especially to the attendant uncertainties is rooted in factors such as: inter-communal trade, joint community projects execution, access to welfare benefits from the government and job creation through small and medium enterprises across the city. Others include cooperative support for local entrepreneurship, economic assistance from international NGOs and the diaspora support for peace and community-building perhaps through remittances (Non-attributable comment, 2021b). All variables under factor three accounted for 8.897% of the variance explained. This is related to how the community members have responded to violent conflict over the years and it is labelled as ‘economic factors’. The development of markets has significantly contributed to the integration of diverse ethnic groups in the Jos metropolis, ensuring that a wide range of goods is accessible not only to local inhabitants but also to those from surrounding areas. The interactions within these markets foster reconciliation, as groups in conflict are compelled to collaborate for their economic survival. Additionally, these market spaces have emerged as critical areas for mediation, facilitating the convergence of conflicting parties. Traders, especially women, play a pivotal role as ‘connectors’, linking various ethnic and interest groups (Lyon et al., 2006; Olu, Adedeji and Abdullahi, 2023; Plateau State Government, n.d.).

Factor four (f4) – traditional justice system and community policing

This category summarises the responses of residents on community resilience to violent conflict regarding the strengthening of the traditional justice system and community policing partnership. The factors also include police response to early warning reports from residents, commissions of inquiry/crimes tribunals and the support for the vigilante group. This article notes an example of how the ability to connect across levels within and among the groups builds and strengthens community resilience to violent conflict in the recent decade. Thus, a socially reinforcing emphasis has emerged, making a case for the identifying of Indigenous leaders and the traditional justice system/institutions that bridge the divide between the diverse warring groups and work with diverse actors (agents of state, CSOs and international NGOs). This is with a view to building strong social cohesion within Indigenous communities and harnessing such for peaceful coexistence among the various groups in the city. The Indigenous system also supports community resilience to violent conflict through the agency of community policing in the city.

Community policing is indeed an instrumental strategy, a philosophy that provides hope and paves the way for conflict resolution and strengthening community resilience when it is nurtured through the willingness of all the stakeholders. The community policing system rests on the philosophy that ensures that the security needs of all segments of the population are considered, which encompasses activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation, continuation and recurrence of violent conflict, addressing root causes and assisting parties to end or resist impending attacks from external aggressors. Essentially, it works as a mechanism in conflict prevention in the city. Thus, it builds resilience to sustain peace through the synergy between the people, vigilante groups and the formal policing system in the city. The factor variables in this category are labelled as ‘traditional justice system and community policing’. These variables under factor four accounted for 8.482%; however, along with the first, second and third factors, they accounted for 41.008% of the total variance explained.

To illustrate successful collaborations between traditional leaders and law enforcement in peacebuilding efforts in Jos, perfect examples can be drawn from the initiatives of the state peacebuilding agency and non-profit organisations. The Plateau State Peacebuilding Agency has frequently empowered local leaders to mediate ethnic and religious conflicts, showcasing specific instances where traditional rulers, alongside law enforcement, helped de-escalate tensions during outbreaks of violence in the city. The partnership between the state and non-state actors also supported community policing. This approach ensured the security needs of all segments of the population were considered. It encompassed activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation and recurrence of violent attacks (Ojewale, 2021; Agabus, 2023).

Factor five (f5) – civic education

This category summarises the responses of residents on community resilience to violent conflict. Factors such as civic education on peacebuilding, training of the people in conflict management, resolution, and prevention and peace sensitisation through media campaigns are aggregated. The factors also include mainstreaming of peace education in schools, churches, mosques and local communities, and public dialogues on peacebuilding. Drawing from the array of interrelated activities and programmes being facilitated by the state and non-state actors in Jos, the findings show that civic education provides a positive framework for collective civic identity. As such, it has become a stabilising factor in the city, considering the protracted negative impacts of violent conflict. Interacting with critical stakeholders such as NGOs, media and community leaders show that civic education programming in the city illustrates the challenges and rewards of developing effective, sustainable models of learning experiences in areas recovering from violence. These involve local engagement, flexibility and long-term commitment, particularly on the part of the residents to inculcate the culture and lifestyle of peaceful coexistence. The process, which remains largely participatory, has been remarkable through the use of deliberative settings for public consultations through town hall meetings, media awareness, inter-religious dialogues and exchanges wherein warring members have had the opportunities to interface and had been given the opportunity to voice their desires and concerns with a view to advance peaceful coexistence among themselves.

In building community resilience to violent conflict in the city, both state and non-state actors facilitate media awareness, town hall meetings, inter-religious dialogues and mainstream peacebuilding education in school curricula. This is done with a view to enlightening and empowering the residents to identify community risks associated with conflict and violence; map indicators of social discontent; promote dialogue and peaceful resolution of conflict; engage among themselves and with formal security institutions; build social coherence; and ensure peaceful out-letting of grievances through individual and collective approaches. The variables in this category are labelled as ‘civic education’. These variables under factor five accounted for 9.410% of the total variance explained. More importantly, barriers to effective civic education implementation in building urban resilience to violent conflict in Jos include a lack of adequate funding, weak institutional capacity and social divisions along ethnic and religious lines. Funding limitations restrict the scope and sustainability of civic education programmes, making it challenging to reach diverse urban populations consistently. Moreover, political influences can skew educational content, focusing on immediate political agendas rather than promoting long-term resilience strategies (Kew, 2021).

Factor six (f6) – non-governmental interventions

This category summarises the responses of residents on community resilience to violent conflict and aggregates the activities and programmes being implemented by the non-state actors. The extant national security strategy in Nigeria encourages broad-based partnerships that accommodate local and international NGOs, local communities, CSOs and community-based organisations in the management of violent conflict. The involvement of non-governmental intervention in building community resilience to violent conflict is a global practice that is also well situated in the Nigerian context. This approach to resilience building is outlined in the work of Norris et al. (2007), which analyses resilience in four adaptive capacities – information and communication, community competence, economic development and social capital. This breakdown of community resilience has helped a number of local and international NGOs to take an effective and practical approach to the complex nature of resilience building in the conflict settings. The impact of violent conflict is felt primarily by the residents, while the cost of managing it might be borne by any or all of the three tiers of government. The government uses a collaborative and consultative approach in an attempt to embed the concept into those organisations (NGOs) that actually have the technical capabilities to improve resilience (Bergin, 2011).

In Jos, NGOs are already embedded and connected at a grassroots level. They are ideally placed to promote messages that build, strengthen and sustain urban resilience to violent conflict, as they exist to support the communities they serve. Furthermore, NGOs have an enduring and trusted presence in the communities and engage a large majority of those communities that are commonly vulnerable to the impact of violent conflict. The strategic involvement of the non-governmental agencies and their subsequent interventions is largely situated in the mandate of the Plateau State Peace Building Agency, as reflected below:

The creation of the Plateau State Peace Building Agency (PPBA) was largely motivated by the desire of ordinary citizens, CSOs, faith-based organizations, international and local organizations and the state government to promote [a] peaceful and stable society in Plateau state. In this sense, PPBA is an agency of the government that is non-partisan, non-religious, non-ethnic, and a hub for coordinating conflict interventions in Plateau state (PPBA, 2018).

The thematic areas of the PPBA are land disputes, mining rights and control, chieftaincy tussles, farmer-herder conflict and boundary disputes. Others are grazing routes, environmental degradation, climate change, media engagement and inequitable distribution of natural resources. Drawing from the above, some residents expressed the view that the activities of NGOs and the interventions in Jos have led to the implementation of activities, such as training of CSOs in conflict-sensitive programming and conflicts management, training of traditional leaders in conflict management and journalists on conflict-sensitive reporting and peace journalism. The constellation of variables in this category is labelled as ‘non-governmental interventions’. These variables under factor six accounted for 7.82% of the total variance explained.

Table 2: Rotated component matrix of factors influencing community resilience to violent conflicts in Jos

| Factor | Resilience initiative | Factor loading | Percentage of variance explained | Cumulative percent of variance explained |

| F1 | MediationSupport through indigenous dispute resolution Community truth and reconciliation groups Inter-religious dialoguesNon-violent campaigns by popular community leadersConflict monitoring and resolution workshopsCultural exchanges | .286 .086 .030.174 .404 .307.292 | 14.09 | |

| 14.09 | ||||

| F2 | Awareness activities by political parties on peace and social cohesionDecentralisation of political powerPromotion of human rights Power-sharing arrangements among various groupsActivities of CSOs on peacebuildingCampaign against violenceInterparty meetings on peaceful electionsParticipation of women and youth in decision-making | .100 | 11.62 | 25.71 |

| .433 | ||||

| .346 | ||||

| .119 | ||||

| .130 | ||||

| .273 | ||||

| .050 | ||||

| .658 | ||||

| F3 | Diaspora support for peace and community buildingInter-communal tradeJoint community projects executionAccess to welfare benefits from governmentJob creation through small- and medium enterprisesCooperative support for local entrepreneurshipEconomic assistance from international NGOsDiaspora support for peace and community building | .152.339.337.167 .255 .144 .161 .152 | 9.89 | 35.65 |

| F4 | Strengthening of the traditional justice systemCommunity policing partnershipPolice response to early warning reports from residentsCommissions of inquiry/crimes tribunalsSupport for the vigilante group | .318 .214 .149.019.367 | ||

| 9.48 | 45.09 | |||

| F5 | Civic education on peacebuildingTraining of people in conflict management, resolution, and preventionPeace sensitisation through media campaignsIntroducing peace education in schoolsIntroducing peace education in local communities Public dialogues on peacebuilding | .525 .189.013 .172 .287.224 | 9.41 | 54.50 |

| F6 | Training of CSOs in conflict-sensitive programming and conflict management | .127 | ||

| Training of traditional leaders in conflict management | .105 | 7.82 | 63.91 | |

| Conflict-sensitive reporting/peace journalism | .365 |

6. Conclusion

This article examines how varying groups such as religious leaders, traditional institutions, community policing groups and a state peacebuilding agency engage and respond to violent conflict in metropolitan Jos. The article analyses initiatives undertaken by communities across different religious, ethnic and social backgrounds to cultivate peaceful coexistence. Communities also work with the Nigerian Police Force, CSOs and international NGOs. The partnership between the state and non-state actors encompasses activities aimed at preventing the outbreak, escalation and recurrence of violent conflict. The study of violent conflict and resilient urban spaces in Jos, Nigeria, highlights the complex interplay between socio-economic factors, community dynamics and institutional responses in shaping urban resilience. Despite the persistent challenges of ethnic and religious divisions, limited resources, and historical grievances, Jos exhibits significant potential for building resilience through inclusive civic engagement, adaptive governance, and community-based peacebuilding initiatives. Strengthening the city’s resilience to violence requires addressing systemic vulnerabilities, fostering collaboration across social divides and empowering local communities to actively participate in conflict prevention and recovery efforts. As Jos continues to navigate these challenges, strategic investments in urban planning, responsive security measures and equitable resource distribution will be essential in fostering a more cohesive and resilient urban environment. This research underscores the importance of a holistic approach that integrates community-led strategies with institutional support to create a foundation for lasting peace and resilience in urban spaces facing the threat of violent conflict. Further research should focus on exploring the role of youth and women in fostering urban resilience, as these groups often play crucial yet underexplored roles in peacebuilding efforts. Additionally, comparative studies between Jos and other urban centres in Nigeria or West Africa that have experienced similar conflicts could provide valuable insights into best practices for resilience building.

Reference List

Agabus, P. (2023) Plateau unrest: International Alert, CLEEN Foundation, inaugurate peace, security platforms. The Authority [Internet], 21 July. Available from: <https://authorityngr.com/2023/07/21/plateau-unrest-international-alert-cleen-foundation-inaugurate-peace-security-platforms/>

Ahiaba, M. (2016) Christian supersessionism and the dilemma of dialogue in Jos Nigeria: exploring Panikkar’s dialogical dialogue as a paradigm for interreligious dialogue. Ph.D. dissertation, Duquesne University.

Ayitogo, N. (2022) Police arrest seven suspected arms dealers in Plateau, Taraba. Premium Times [Internet], 28 April. Available from: <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/526562-police-arrest-seven-suspected-arms-dealers-in-plateau-taraba.html>

Bergin, A. (2011) King-hit: preparing for Australia’s disaster future. Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

Björkdahl, A. (2013) Urban peacebuilding. Peacebuilding [Internet], 1 (2), pp. 207–221. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2013.783254>

Bourbeau, P. (2013) Resiliencism: premises and promises in securitisation research. Resilience, 1(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.765738

Brück, T. et al. (2009) Measuring violent conflict in micro-level surveys: current practices and methodological challenges Policy Research Working Paper 7585. Washington, D.C., World Bank Group.

Chandler, D. (2012) Resilience and human security: The post-interventionist paradigm. Security Dialogue, 43(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010612444151

Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. (2013) The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue: Inter- communal dialogue and conflict mediation in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Roadmap/Agenda for Discussion. Geneva, Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue.

Channels TV. (2022) Over 500 small arms, light weapons recovered in Plateau State. Channels TV [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4kTRN8AeBaw>

Child, D. (2006) The essentials of factor analysis. 3rd ed. New York, Continuum International Publishing Group.

Emerson J.D and Stoto M.A., (1983) Transforming data. In: Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F and Turkey JW. eds. Understanding Robust and Exploratory Data Analysis. New York: Wiley, pp. 97–128.

Green, S. and Salkind, N. (2003) Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: analyzing and understanding data. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J., Prentice Hall.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). (2017) I saw my city die: voices from the front lines of urban conflict in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. ICRC [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/i-saw-my-city-die-voices-front-lines-urban-conflict-iraq-syria-and-yemen>

Kaldor, M. and Sassen, S. (2020) Cities at war: global insecurity and urban resistance. New York, Columbia University Press.

Kim, J. and Mueller, C. (1978) Factor analysis: statistical methods and practical issues. Beverly Hills, CA, Sage.

Kew, D. (2021) Nigeria’s state peacebuilding institutions: early success and continuing challenges. Special Report. Washington, D.C., United States Institute of Peace.

Krause, J. (2011) A deadly cycle: ethno-religious conflict in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Geneva, Geneva Declaration Secretariat.

Kwaja, C. (2014) Responses of Plateau State government to violent conflicts in the state. Nigeria stability and reconciliation program, Policy Briefs No. 5.

Lake, D. (2010) Two cheers for bargaining theory: assessing rationalist explanations of the Iraq war. International Security, 35 (3), pp. 7–52.

Ljungkvist, K. and Jarstad, A. (2021) Revisiting the local turn in peacebuilding – through the emerging urban approach. Third World Quarterly [Internet], 42 (10), pp. 2209–2226. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1929148>

Lyon, F. et al. (2006) The Nigerian market: fuelling conflict or contributing to peace. In: Banfield, J., Gunduz, C. and Killick, N. eds. Local business, local peace: the peace building potential of the domestic private sector. London, International Alert. pp. 432–437.

Marshall NA, Stokes C, Nelson RN, et al. (2010) Enhancing the adaptive capacity of agricultural people to climate change. In: Stokes C and Howden SM .eds. Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change. CSIRO Publishing.

Madueke, K.L. (2019) The emergence and development of ethnic strongholds and frontiers of collective violence in Jos, Nigeria. African Studies Review [Internet], 62 (4), pp. 6–30. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2018.115>

Nanlong, M-T. (2023) Women groups seek inclusion in community policing, others. Vanguard [Internet], 6 April. Available from: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2023/04/women-groups-seek-inclusion-in-community-policing-others/>

Nguyen KV and James H (2013) Measuring household resilience to floods: A case study in the vietnamese mekong river delta. Ecology and Society, 18(3), pp. 1–13.

Non-attributable comment on 10 August 2022(a). Jos. [Transcript in possession of author].

Non-attributable comment on 19 August 2022(b). Jos. [Transcript in possession of author].

Non-attributable comment on 12 November 2021(a). Jos. [Transcript in possession of author].

Non-attributable comment on 22 November 2021(b). Jos. [Transcript in possession of author].

Norris, et al., (2007) Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology [Internet], 41 (1–2), pp. 127–150. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6>

Ofori, G., & Lean, C.S. (2001) Factors influencing development of construction enterprises in Singapore. Construction Management and Economics, 19, pp.145–154.

Ojewale, O. (2021) Violence is endemic in North Central Nigeria: what communities are doing to cope. The Conversation [Internet], 23 June. Available from: <https://theconversation.com/violence-is-endemic-in-north-central-nigeria-what-communities-are-doing-to-cope-157349>

Olu, D.J., Adedeji, B.S., and Abdullahi, U.M. (2023) Market traders and inter-group relations in Jos main market, 1975–2023. Wukari International Studies Journal [Internet], 7 (3), pp. 63–77.

Plateau State Government. (n.d.) Plateau State is open for business: Investors’ Guide. A document produced by the Jos Business School (JBS) for the Plateau State One Stop Investment Center (OSIC) [Internet]. Available from: <https://www.plateaustate.gov.ng/uploads/Investing-in-Plateau-State-OSS-booklet.pdf>

Plateau Peace Building Agency (PPBA). (2018) Plateau State road map to peace: PPBA Strategic Action Plan (2018–2022). PPBA [Internet], 8 March. Available from: <https://www.plateaupeacebuilding.org/images/PPBA%20ROAD%20MAP.pdf>

Sadiq, L. (2016) The tale of the Plateau’s war against arms proliferation. Daily Trust [Internet], 23 October. Available from: <https://dailytrust.com/the-tale-of-the-plateaus-war-against-arms-proliferation>

Stevens, J. (1992) Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Stevens, J. (2002) Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences (4th Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sticher, V. and Vuković, S. (2021) Bargaining in intrastate conflicts: the shifting role of ceasefires. Journal of Peace Research [Internet], 58 (6), pp. 1284–1299. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320982658>

Tabachnick, B. and Fidell, L. (2001) Using multivariate statistics: international student edition. 4th ed. London, Allyn and Bacon Publishers.

Trost, S. and Oberlender, G. (2003) Predicting accuracy of early cost estimates using factor analysis and multivariate regression. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 129 (2), pp. 198–204.

World Bank. (2011a) Violence in the city: understanding and supporting community responses to urban violence. Working Paper. Washington, D.C., World Bank Group.

World Bank. (2011b). World Development Report 2011: conflict, security, and development. World Bank Group [Internet]. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8439-8>