In Africa, one of the most important repositories of history, culture and ecology is the Lake Chad Basin (LCB), which has accurately been described as ‘an African geosymbol in a class of its own.’1Magrin, Géraud (2002) ‘The disappearance of Lake Chad: History of a myth’, Journal of Political Ecology, 23(1), 204–222, p. 205. That Lake Chad is a strategic and important natural resource has captivated global attention and concerns over the decline and withering of the Lake. The situation has been made worse by the recent upsurge in violent conflict and confrontation in the region, thus making the region a hotspot for insecurity. This is not disconnected from the emergence and activities of the Boko Haram group, who have been carrying out an insurrection in northern Nigeria over the past few decades. The terrorist group has leveraged the largely porous borders of the countries in the LCB, among other features, to use the Lake Chad Region (LCR) as fertile ground to expand their influence and acquire havens for their illicit ventures. Military operations to counter the insurgency have equally pushed back the sect into the fringes of the LCR, thereby leading to the trans-nationalisation of the insurgency across the riparian countries of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. The trans-nationalisation of the insurgency across the fragile region has exacerbated an already complex crisis and has overstretched and overburdened LCB countries.2Onuoha, Freedom (2014) ‘Why do Youth Join Boko Haram?’ Available at: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR348-Why_do_Youth_Join_Boko_Haram.pdf [Date accessed: 17 August 2024]. The sect’s swift rise to prominence due to the havoc caused by its activities and its resilience and tenacity in carrying out large-scale, trans-border attacks have necessitated sub-regional commitments and cooperation among the affected countries.

The new security realities have compelled regional collaboration for effective and results-based Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Insurgency (CT-COIN) as a form of securitisation of the LCR. Thus, the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) was established as a product of multilateral security cooperation and as a robust regional outfit that will serve as a mechanism to transform the existing structure of the LCB and respond to the pressing security challenges in the region. Therefore, this paper explores the emerging regionalisation of (in)security in the LCB under the auspices of the MNJTF as a response to sub-regional threats to peace and security. The article contributes to the academic and policy literature on the nature, dimension, and conduct of regional security provision and complexes in conflict-affected areas. It further contributes to the ongoing debate on the viability of the MNJTF operations in the LCB as a regional security complex.

The article is divided into five sections. After the introduction, the second section deals with the conceptual explication of a regional security complex (RSC). While the third section examines the MNJTF as a regional security complex for CT-COIN in the LCB, the fourth section interrogates the performance and successes of the MNJTF as a regional security architecture in the LCB. Lastly, the fifth section provides the conclusion of the article.

Regional Security Complex: A conceptual overview

Regionalism and the conceptualisation of regions as groupings of proximate states embedded within a historical and geographical context have garnered much attention in the study of international relations theory during and after the Cold War. The focal point for constructivists in the development of a ‘new world order’ has been dominated by regionalism and regional analysis characterised by the belief that regional groups are bound together by shared identities, values and cultures.3Cruden, Michaela (2011) Regional Security Complex Theory: Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, Doctoral dissertation, University of Waikato. In order to conceptualise the RSC, it is imperative that the terms ‘region’ and ‘security’ be clarified due to the nature and dynamics of ‘security complexes.’ Regions, in their simplest form, are defined as geographically proximate and independent states. Regionalism is defined as attempts at formal cooperation between such states. More elaborately, a region is “a set of countries that are, or perceived themselves to be, politically independent,”4Lake, David and Morgan, Patrick (1997) ‘The New Regionalism in Security Affairs’, in: Lake, D. and Morgan, P. (Eds.), Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World,University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 11. and “exhibit a particular degree of regularity and intensity to the extent that a change at one point in the (system) affects other points.”5Thompson, William (1973) quoted in Lake, David and Morgan, Patrick (1997) ‘The New Regionalism in Security Affairs’, in: Lake, D. and Morgan, P. (Eds.), Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World,University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 11.

The concept of security, on the other hand, has evolved past its traditional roots of subjectivity to the military or political sphere and it can no longer be considered as the sole referent object of security for the development of a secure and strong state. Security is re-conceptualised as a situation where the survival of the referent object (which is the reason behind the securitisation process) is at the forefront of a security agenda that necessitates the adoption of emergency measures and actions within the political sphere.6Buzan, Barry (2003) Regions and Power: The Structure of International Security, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 98–99. Furthermore, a security threat can be referred to as an issue that ‘is posited (by a securitising actor) as a threat to the survival of some referent object (nation, state, the liberal economic order, […]), which is claimed to have a right to survive.’7Eisenstat, Stuart E. and Weinstein, John E. (2005), quoted in Šehović, Annamarie (2018) ‘Identifying and addressing the governance accountability problem’, Global Public Health, 13(10), 1388-1398, p. 1393. Therefore, the nature of security complexes is so interlinked that to combat threats to regional stability and ensure maximum security across the wider region, it is imperative that states cooperate and coordinate their relationships in a harmonised manner as far as such threats need to be wholly mitigated. This creates a foundation for the securitisation process, the central idea of which is that threats are treated equally by all parties involved as a mutual concern that requires mutual action. The concept of an RSC connotes:

a group of states whose primary security concerns link together sufficiently closely that their national securities cannot realistically be considered apart from one another. Therefore, the core elements in a regional security complex are its interactions in the form of security relationships and the components of interdependence that relate to security.8Buzan, Barry (1991), quoted in Morgan, Patrick (1997) ‘Regional Security Complexes and Regional Orders’, In: Lake, D. and Morgan, P. (Eds), Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World,University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 25.

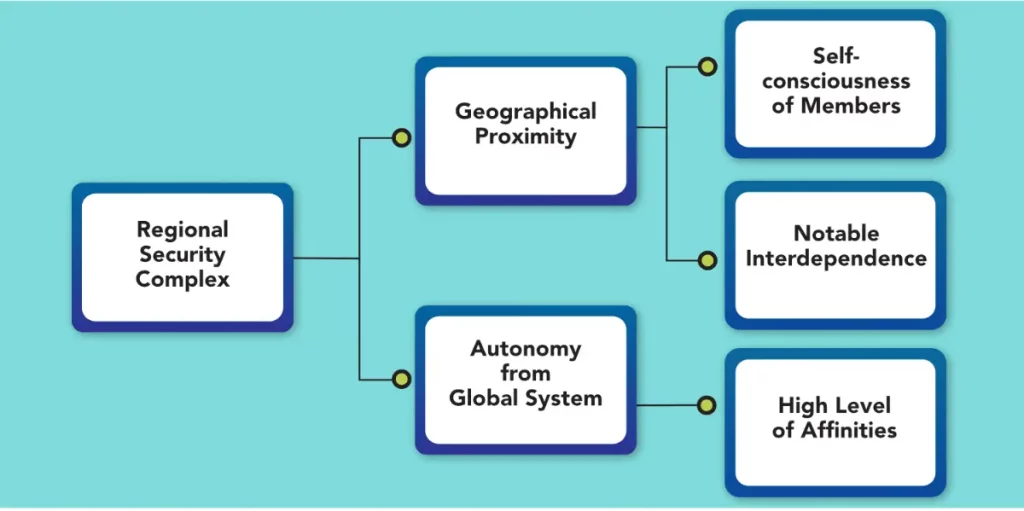

The criteria for RSC are depicted in Figure 1.

For the purpose of this paper, which is focused on examining RSC for CT-COIN operations in the LCB, and in view of the examination of the concept of RSC herein in this regard, this paper appropriates Barry Buzan’s position on RSC. Put simply in his arguments, an RSC can be conceived as a geographical region with a delineated pattern of security relationships and autonomous dispositions from the global system with interlinked security perceptions and concerns that cannot realistically be separated from one another.9Buzan, Barry (2003) Regions and Power, op. cit.

The MNJTF as a regional security architecture in the LCB

Regional CT-COIN is a concerted effort by several continental, regional and international bodies committed to curbing the scourges of terrorism and insurgency. Based on historical evidence in the LCB, security threats and events in the form of trans-national organised crime, cross-border incursions, and political violence among member states have had dire consequences on the peace and security of the region and have compelled cooperation and collaborative efforts to counter such threats. For instance, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) was formed by the LBC countries of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria on 22 May 1964 as a multilateral framework for the management and preservation of the aquatic resources of the LCR.

However, in the 1990s, the excesses of trans-border crimes, robbery, rustling and banditry within the LCB compelled the expansion of the operational mandate of the LCBC, which birthed the establishment of a Multinational Task Force to combat these challenges. Similarly, the evolution and trans-nationalisation of the Boko Haram insurgency, coupled with the long-overdue collaborative efforts between Nigeria and her immediate neighbours, translated into the quest for a regional dimension of securitisation. This new threat necessitated that the LCB countries revisit and remodel the structure and doctrine of the MNJTF when they converged at the 14th Summit of Heads of State and Government in April 2012. This move was regarded as one of the first instances when governments showed any real commitment to the force, and it led to its institutionalisation at Baga on the Nigerian shores of the Lake region. Its operational mandate was elevated to accommodate joint and combined military offensive actions to counter Boko Haram incursions in the LCR.

The African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council’s (PSC) 2015 report on Boko Haram and other international threats spells out the operational mandate of the MNJTF as follows:

- Create a safe and secure environment in the areas affected by the activities of Boko Haram and other terrorist groups, in order to significantly reduce violence against civilians and other abuses, including sexual- and gender-based violence, in full compliance with international law, including international humanitarian law and the United Nations HRDDP [Human Rights Due Diligence Policy];

- Facilitate the implementation of overall stabilisation programmes by the LCBC Member States and Benin in the affected areas, including the full restoration of state authority and the return of internally displaced people and refugees; and

- Facilitate, within the limit of its capabilities, humanitarian operations and the delivery of assistance to the affected populations.10AU PSC (2015) ‘Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the implementation of communiqué PSC/AHG/COMM.2(CDLXXXIV) on the Boko Haram terrorist group and on other related international efforts’, AU, Adis Ababa, pp. 2–3.

The AU also rendered its support through informed discussions with the four LCB countries by convening a meeting of experts to design and define the practical steps needed to be adopted for the achievement of the objectives of the MNJTF, as enshrined by the Abuja ministerial meeting of 13 October 2014. The agreed practical steps to be adopted by the countries of the region include the re-establishment of the headquarters of the MNJTF in N’Djamena, Chad, the establishment of a secured communication network for the security forces operating in and around the LCB, and the timely finalisation of the coordination and liaison cell to be established in N’Djamena.11Bala, Bashir and Tar, Usman Alhaji (2019) ‘Emerging Architecture for Regional Security Complex in the Lake Chad Basin: The Multinational Joint Task Force in Perspective’, In: Tar, Usman Alhaji and Bala, Bashir (Eds),New Architecture of Regional Security in Africa: Perspectives on Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Insurgency in the Lake Chad Basin, United States: Lexington Books, pp. 141–166. The AU PSC, in conjunction with the four member states of the LCB, pledged to develop a full Concept of Operations (CONOPS), which was finalised in March 2015 and had the mandate of outlining the details of political oversight, command structures, objectives, tasks and missions of the task force.

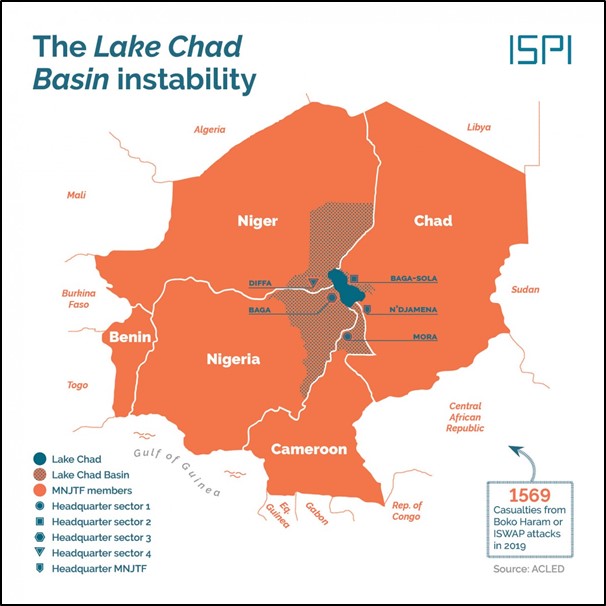

The force’s key aim, as identified by the CONOPS, is eliminating the presence and influence of Boko Haram in the region. Having undergone these adjustments, the MNJTF became fully activated on 30 July 2015, with a combined military force of 11 000 troops authorised by the AU and comprising troops from Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Benin (who joined the fight against Boko Haram in 2012). Thus, the MNJTF was transformed into a defensive, offensive and stabilisation force to deal with the scourges of terrorism and insurgency in the LCB. The operational area, as prescribed by the CONOPS for the MNJTF, covers Lake Chad and extends across the borders between Nigeria and Niger. Although headquartered in N’Djamena, the task force is commanded by a Nigerian General. To guarantee the sovereignty of member states and the ease of operations, the operational combat zone of the terrorist groups was divided into four sectors, with member states given responsibility for each sector. Figure 2 illustrates the deployments of the MNJTF. From Figure 2, it can be seen that each sector has its own headquarters located in each of the four countries and in the following order: Sector 1 is located in Cameroon and headquartered at Mora, Sector 2 is located in Chad with headquarters in Baga-Sola, Sector 3 is located in Nigeria with headquarters in Baga, and Sector 4 is located in Niger and with headquarters in Diffa.

The LCB crisis: Has the MNJTF made a difference?

With its current capacity and configuration and in its role as a regional security actor with the mandate to confront and counter emerging regional security challenges in the LCB, the MNJTF has recorded considerable success despite operational and tactical challenges. Through contributions from Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Benin, the task force increased its troops from 7 600 in 2015 to 10 250 by July 2019. Although 2015 marked the first year of the MNJTF, with much focus and attention on its establishment and the definition of its mode of operation, 2016 ushered in a new phase in the fight against Boko Haram due to multiple successes recorded by the MNJTF. Among the most significant operations carried out simultaneously by the sectors of the MNJTF was Operation Gama Aiki (meaning ‘Finish the work’ in Hausa) from June to November 2016 around the fringes of Lake Chad and into Borno state, Nigeria. What made the Operation stand out against others was the notable success of the MNJTF in liberating certain areas held by Boko Haram, releasing many hostages, recovering sophisticated weapons, and crippling the combat efficiency of Boko Haram. Likewise, an operation in November 2016 by Sector 2 of the Baga-Sola Battalion of Chad ultimately led to the surrender of at least 240 Boko Haram fighters, and an operation carried out by Sector 1 in Cameroon between February and May 2016 led to the destruction of many Boko Haram training camps.

The MNJTF has also collaborated with sister agencies, such as the Nigerian Air Force, who provided aerial cover in June 2016 for the MNJTF in an air strike operation that was targeted at identifying and bombing various enclaves of Boko Haram within the LCB. It is these concerted efforts by the MNJTF, adhering to its mandate and maintaining discipline in carrying out its operations, which have resulted in the crippling of Boko Haram’s ability to wreak more socioeconomic havoc and worsen the humanitarian crisis in the LCR.13Albert, Isaac Olawale (2017) ‘Rethinking the Functionality of the Multinational Joint Task Force in Managing the Boko Haram Crisis in the Lake Chad Basin’, Africa Development/Afrique et Development, 42(3), 119–135. Overall, the MNJTF has succeeded in giving the LCB states a sense of shared responsibility towards collective defence and deterrence by emerging as a strong force that could withstand threats and counter the increasing waves of insurgency and terrorism in the region. Considering the magnitude of attacks carried out by Boko Haram and their stern presence along communities bordering the LCB countries, the MNJTF’s operational activities in collaboration with other national forces have duly activated a considerable level of defence and protection against the sect’s terror along these distressed border communities.

The MNJTF’s activities have been calibrated towards the deterrence of Boko Haram attacks through the force’s offensive operations and pre-emptive strikes at various Named Areas of Interest (NAIs) to Boko Haram. This has led to the death or apprehension of many members of the sect and the shattering of their planned offensive strikes. Notable among these were the MNJTF’s Operation Gama Aiki II in 2017 and Operation Amni Faka (Peace at All Costs) in 2018, both aimed at pushing back the insurgents and lasting about three months. In these operations, the Chadian forces, in particular, were the dominant forces that penetrated deeply into the Nigerian territory and exerted much force beyond even its Cameroonian and Nigerian counterparts, although some costs of the operations were reportedly covered by the Nigerian government and paid directly to the Chadian government.14Mutah, Jude (2021) Transnational Cooperation to Combat Boko Haram: The Multinational Joint Task Force (MJNTF), Doctoral dissertation, University of Baltimore, pp. 23–25.

Although the gains of these operations were difficult to consolidate due to weaknesses on the part of the Nigerian government to devise efficient responses to the highly resilient Boko Haram, the contributions of the LCB countries of more troops to fight the insurgents should not be overlooked. This is particularly concerning the weakening of Boko Haram’s combat efficiency and its ability to take control over territories and military bases and installations. These operations have largely contributed to the realisation of the principle of collective defence and security and cross-border cooperation and they can be considered significant successes of CT-COIN in the LCB.

Conclusion

The evolution and activities of the Boko Haram insurgent group in northern Nigeria and its spillover into the LCR necessitated that states of the LCB call for regional securitisation through cooperation and commitments along a shared course. To form a defence alliance within the framework of regional cooperation, member states of the LCBC reinvented, revived and re-invigorated the MNJTF, which was earlier formed to address the developmental and ecological challenges that confronted the region to meet the emerging challenges of terrorism and insecurity. Boko Haram has demonstrated much tenacity and resilience in efforts to achieve its aims, which has made neutralising the sect difficult. However, the MNJTF has recorded considerable successes in weakening the capacity and combat efficiency of Boko Haram. In conclusion, the MNJTF serves as a viable case study for future regional security complexes in resolving conflicts, promoting regional cooperation, and enhancing military diplomacy. By linking its mandate to broader political strategies, the MNJTF demonstrated the positive impacts of civil-military coordination and fostering partnerships between military and civilian agencies and even between member states of regional organisations.

Nufaisa Garba Ahmed is a Lecturer at the Department of Defence and Security Studies, Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA). She holds a PhD in Defence and Strategic Studies, M.Sc. in Defence and Strategic Studies, Masters in International Affairs and Diplomacy (MIAD) and B.Sc International Studies. She is an Associate of the Society for Peace Studies and Practice (SPSP) and Non-Resident Fellow, Irregular Warfare Initiative of the Modern War Institute at West Point, United States.