Historically, regime changes in both the global North and South are closely linked. The process of change often results in the establishment of democracy, a return to authoritarianism, or the emergence of revolutionary systems.1Mainwaring, S. (1989) ‘Transitions to Democracy and Democratic Consolidation: Theoretical and Comparative Issues’, Kellogg Institute for International Studies, working paper 130, p. 4. The oscillation between non-representative regimes and democracy is frequently a consequence of political and social instability, originating from social and economic inequalities between the wealthy and the poor.2Agemoglu, D. and Robinson, A.J. (2001) ‘A Theory of Political Transitions’, The American Economic Review, 91(4), 938–963. As such, political transitions are often easier to achieve during periods of economic recession due to the lower associated costs.

Economic hardships increase the likelihood of revolution or coups. Often, the impoverished majority resort to civil unrest to express dissatisfaction with the country’s low level of development and government mismanagement of public funds. This popular discontent is often accompanied by elite or military officers seizing power from the incumbent government, promising economic improvement or strengthened homeland security. Throughout history, many political transitions have occurred during economic recessions, including in Brazil (1964), Chile (1973), Argentina (1976), Burkina Faso (1983), Mali (1991), and Niger (1999).

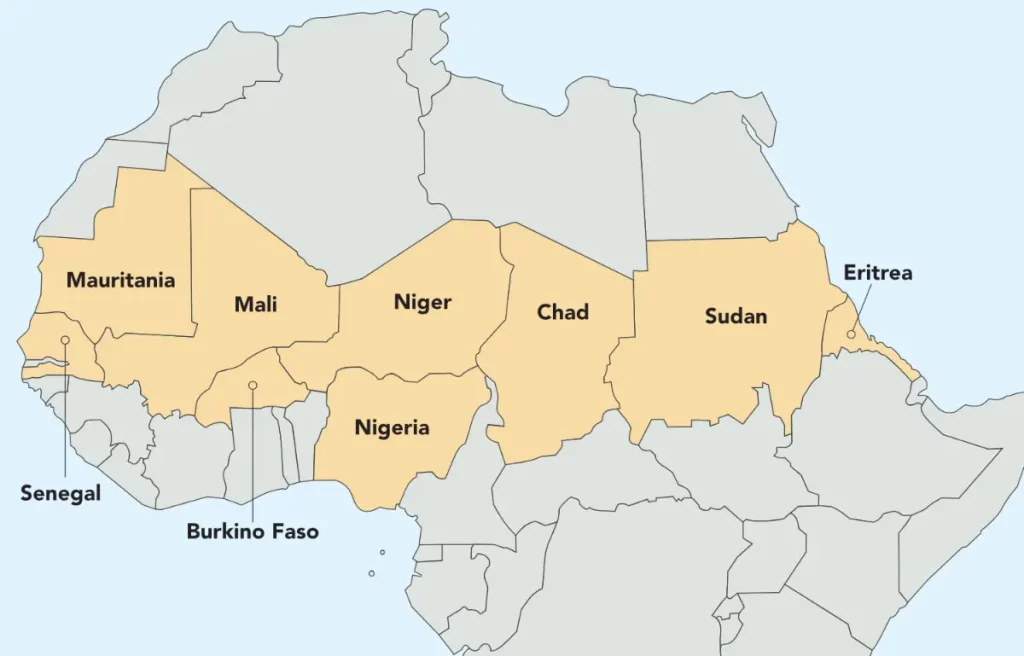

In recent years, Burkina Faso (2022), Gabon (2023), Guinea (2022), Mali (2021), and Niger (2023) have all experienced coups within a short span of time. Four of these countries are members of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), while one belongs to the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). The African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) condemned the military takeovers and called for a swift return to constitutional order in these regions.3AU PSC (2024) ‘Communiquer on political transition in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger’, 20 May, PSC/PR/COMM.1212; Amani Africa (2024) ‘Briefing on Political Transitions in Africa’, 19 May.

Despite having significant natural resources such as gold, nickel, bauxite and other metal ores, coal, manganese, phosphate, oil and uranium, the economies of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are weakened by high rates of corruption, taxation, and unemployment.4Bassou, A. (2024) ‘From the Alliance of Sahel States to the Confederation of Sahel States: The Road is clear, but full of traps’, Policy Centre for the New South, policy brief 19/24, April. Beyond economic challenges, the Liptako-Gourma region of the Sahel faces significant security threats from jihadist insurgencies, which have been ongoing since 2010, displacing populations and further undermining the democratisation process.5Raudais, v., Bourhrous, A., & O’Driscoll, D. (2021) “Conflict Mediation and Peacebuilding in the Sahel: The Role of Maghreb Countries in an African Framework”. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, No.58, pp. 1–34.

The deteriorating economic and security situation in the central Sahel has provided a pretext for high-ranking military officers, who viewed the governments as inept, to overthrow the incumbent administrations and establish revolutionary regimes. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have experienced a total of 26 coups, with seven being unsuccessful attempts.6VOA News (2024) ‘Coups in Africa’, Available at: https://projects.voanews.com/african-coups [Date accessed: 14 July 2024]. This pattern has persisted since independence, with senior military officials frequently interfering in governance, often suspending constitutions, dissolving parliaments, and indefinitely postponing elections.

In response, ECOWAS imposed sanctions such as non-diplomatic recognition, refusal of foreign aids, and imposition of embargoes aimed at restraining putschist’s power and forcing a quick return to constitutional order.7Mcglinchey, S.; Walters, R.; and Scheinpflug, C. (2017) International Relations Theory, Bristol, UK: E-International Relations. These sanctions were partially effective in the past, as ECOWAS’ military intervention helped restore democratic governments in Liberia (1990), Sierra Leone (1997), Guinea Bissau (1999), Côte d’Ivoire (2003), Liberia (2003), Mali (2013) and the Gambia (2017).8Aljazeera News (2023) ‘Timeline: A history of ECOWAS military interventions in three decades’, 1 August, Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/1/timeline-a-history-of-ecowas-military-interventions-in-three-decades [Date accessed: 3 August 2024].

Olukayode Bakare unravels how Nigeria used its military strength (in ECOWAS and the AU) to play an active role in maintaining peace and democracy, and strengthen its influence, particularly in the West African sub-region.9Bakare, O. (2019) ‘The Nigeria-Commonwealth and UN Relations: Nigeria, from Pariah State to exporter of democracy since 1999’, Cogent Social Sciences,5(1), 1–14. Yet, Bakare failed to discuss how the Nigerian military expeditions within ECOWAS could not guarantee a democratic culture within the region. Equally, the persistent dysfunction of democracy and frequent military expeditions weakened ECOWAS’ authority. Central Sahel member states did not appreciate acts of intimidation and violation of their sovereignty. Thus, in an attempt to protect themselves against ECOWAS’ military intervention, the Alliance of Sahel States (ASS) was established in September 2023, as a mutual defence task force.10Aljazeera News (2023) ‘Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso establish Sahel security alliance’, 16 September, available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/16/mali-niger-and-burkina-faso-establish-sahel-security-alliance [Date accessed: 3 August 2024].

The violation of its economic mandate to incorporate (over the years) military missions weakened ECOWAS’ ability to provide African solutions to African problems. This is because, during the transitional period, several coup leaders tried to undermine the legitimacy of ECOWAS’ interventions in their domestic affairs. Moreover, Morgenthau, Osgood, Waltz, and Van Evra are scholars who used realist’s tenets to argue that transnational organisations violate state sovereignty through its desire to exercise substantial influence on world politics.11Mcglinchey, S.; Walters, R.; and Scheinpflug, C. (2017) International Relations Theory, Bristol, UK: E-International Relations. These scholars further maintained that, states, as primary actors of international relations, would undermine the influence of transnational organisations in their pursuit of power and/or security. Thus, ECOWAS’ intervention into the domestic affairs of central Sahel states is considered, by military leaders, to be a violation of their territorial integrity.

Consequently, political transition in central Sahel remains a complex governance issue that needs a comprehensive analysis, specifically of the region’s constitutional and political realities. This work raises and answers key questions: Why did previous political transitions fail? How does the population perceive democracy? Is democracy necessary for development in the Sahel?

The failure of previous political transitions

The early 1990s marked a significant shift in French-speaking African countries, including Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, from one-party systems to multiparty democracies. However, this political development was preceded by trade union strikes and protests by students, unemployed graduates, and secret consortiums. Democracy was thus introduced, either through violence or through passive constitutional adjustments, but the democratisation process was plagued by inefficient political, economic, and social policies.

Political failures

Under the one-party system of administration, criticism and emerging opposition unions that challenged the legitimacy of the totalitarian regime were not tolerated in Sahel countries. This led to the centralisation of government power, press censorship, and the banning of trade unions. With the absence of trade unions and freedom of expression, strikes were considered illegal. As such, the transition to democracy in the 1990s was seen by many in the Sahel as a gateway to political freedom and peaceful power alternation. However, the transition was more effective on paper than in practice since several political leaders attempted to revert to the one-party leadership style. In central Sahel countries, state-owned media became propaganda outlets, and parliamentarians were not allowed to question government actions.12Sako, S. (2014) ‘Crisis in Mali: Lessons from an ongoing democratic transition’, Transitions Forum, November, p. 7. The electoral process was often condemned, and opposition leaders, journalists, and civil society members were suppressed. Moreover, incumbents attempted to amend constitutions to extend their terms indefinitely. For instance, violent riots preceded the resignation of President Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso due to his unconstitutional bid for a fifth term.13Engels, B. (2015) ‘Political transition in Burkina Faso: The Fall of Blaise Compaoré’, Governance in Africa, 2(1), 1–6, http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/gia.ai

With the growing absence of checks and balances, the separation of powers, and freedom of expression, democracy became ineffective in preventing the oscillation of violent protests in the central Sahel as citizens rejected unconstitutional actions that recreated an environment reminiscent of the one-party era. Political repression, bad governance, and revolutions further weakened the democratisation process in central Sahel countries.

Economic failures

With the advent of democracy, the population expected greater government accountability, improved management of state resources, better living conditions, and job creation. In most Sahel countries, the government sought to create various sources of employment and reduce dependency by liberalising the economy. This action attracted Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which led to the establishment of mining and textile companies in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger but did not adequately solve the employment problem as expected.

By 2015, the unemployment rate in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger exceeded 30%, with a gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 5.4%, 5.1% and 5.8%, respectively, which significantly impacted the dependency ratio and increased the burden on family welfare and the government.14Sako, S. (2014) ‘Crisis in Mali’, op. cit., p. 8; Bassou, A. (2024) ‘From the Alliance of Sahel States to the Confederation of Sahel States: The Road is clear, but full of traps’, Policy Centre for the New South, policy brief 19/24, April, p. 4. This situation was further exacerbated by security issues, corruption, and embezzlement. Under the leadership of Blaise Compaoré in Burkina Faso and Younoussi Touré in Mali, several government officials were accused of corruption and misappropriation of public funds. Equally, the rise in unemployment forced many to rely on civilian and military recruitment for income, a process often marred by favouritism and corruption.15[1] Sako, S. (2014) ‘Crisis in Mali: Lessons from an ongoing democratic transition’, Transitions Forum, November, p. 8. Consequently, the disenfranchised population either migrated to neighbouring countries for better opportunities or engaged in violent protests demanding improved living conditions.

Both alternatives were detrimental to the democratisation process in central Sahel countries. On the one hand, protests weakened government’s control over the population.16[1] Bratton, M and van de Walle, N (1992) Protest and Political Reform in Africa. Comparative Politics, 24(4), pp. 419–442. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/422153 On the other hand, terrorist attacks, often led by Tuaregs who had migrated for economic reasons, further destabilised the region.17Keita, K. (1998) ‘Conflict and conflict resolution in the Sahel: The Tuareg insurgency in Mali’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 9(3), 102–128. In 2014, a faction of al-Qaeda attacked Ouagadougou a few months after Roch Kaboré succeeded Compaoré as President of Burkina Faso. In Mali, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta’s administration faced repeated terrorist attacks, and in Niger, after the first peaceful transition since 1960, President Bazoum confronted spiralling terrorist violence.18Morand J., & Wurlod K. (2022) ‘Parliamentary oversight of the security sector and political transition: Lessons from Niger’, DCAF Policy Paper, 1–5.

The government’s inability to address unemployment, famine, corruption, and underdevelopment created a vacuum in its relationship with the population. Unfortunately, this vacuum was filled by violent state actors who contributed to the dysfunction of democratic governance. Amid these economic and security challenges, military officers seized power and established revolutionary systems with the aim of restoring stability in the central Sahel.

Social failures

Infrastructural development in the central Sahel, particularly in road construction, schools, and low-cost housing, has been inadequate. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have literacy rates of 36.5%, 35.6%, and 19.1%, respectively.19Bassou, A. (2024) ‘From the Alliance of Sahel States to the Confederation of Sahel States’, op. cit. Several factors contribute to these low rates, including the long distances children must travel to reach schools.20Sako, S. (2014) ‘Crisis in Mali’, op. cit. The nomadic pastoral culture in the Sahel further complicates access to education. Government failure to provide adequate schools, coupled with the impact of climate change on agriculture, has driven many Tuaregs to migrate to urban areas, where their skills are less valuable. In urban centres, many Tuaregs became beggars and are thus easily recruited by radical Islamist leaders who promise them better living conditions.21Sako, S. (2014) ‘Crisis in Mali’, op. cit.; Keita, K. (1998) ‘Conflict and conflict resolution in the Sahel: The Tuareg insurgency in Mali’, op. cit. This recruitment fuelled insecurity in all central Sahel countries, leading to military coups amidst volatile homeland security.

The current military transition in the central Sahel

The transitional period in central Sahel is characterised by uncertainty. This uncertainty stems from the military leaders’ refusal to adhere to the 24-month transitional period initially proposed by ECOWAS.22Amani Africa (2024) ‘Briefing on Political Transitions in Africa’, 19 May. Elections have been postponed multiple times, and ECOWAS imposed economic sanctions on central Sahel states in an effort to enforce a fixed electoral timeline and facilitate a quick return to constitutional order. Unfortunately, the military authorities do not share the same priorities as ECOWAS, focusing instead on combating terrorism.

In Mali, after twice postponing elections (in February 2022 and September 2023), in May 2024, the transitional authority indefinitely postponed the organisation of elections. The reason advanced was the volatile security situation in the region. Members of some political parties, journalists, and activists expressed their concern about the willingness of the military authorities to return power to a civilian administration.23African Union’s Communiqué on political transition in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger. 20 May 2024 PSC/PR/COMM.1212 (2024).

Equally, the press is monitored by the government and activists and political activities are suspended. The media has been accused of creating fear in the population or encouraging acts of rebellion against the government, and they are thus either banned or suspended. The military authority in Mali decided to suspend the activities of all political parties, and focused its efforts on providing basic needs (electricity, water, shelter) to the population.24ISS Today (2024) ‘Stability in Mali requires more inclusive national dialogue’ 15 July, available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/stability-in-mali-requires-more-inclusive-national-dialogue [Date accessed: 4 August 2024]. Furthermore, some communities in Burkina Faso received agricultural subventions from the military government to boost their agricultural productivity.25[1] Agence Ecofin (2024) ‘Burkina Faso : le gouvernement débourse 128 millions $ pour soutenir la campagne agropastorale 2024/2025’ 7 May, available at: https://www.agenceecofin.com/agro/0705-118463-burkina-faso-le-gouvernement-debourse-128-millions-pour-soutenir-la-campagne-agropastorale-2024/2025 [Date accessed: 3 July 2024]. In Niger, military authorities decided to embark on reforming the mining sector to encourage companies to be compliant with government’s sustainable development objectives. Above all, central Sahel military leaders strengthened their efforts to fight issues of corruption, embezzlement, and favouritism that affect good governance.

Moreover, the military authorities believed fighting the upsurge of terrorist attacks and their consequential human casualties among the populations of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger is the priority. This focus led to a geopolitical reconfiguration of actors in the region. It was such that military-led Sahel countries withdrew permanently from the Group of Five Sahel (G-5 Sahel), which caused the dissolution of the G-5 Sahel. By withdrawing from the G-5 Sahel, the three military leaders, in September 2023, established the ASS as a task-force to coordinate their military actions.26Bassou, A. (2024) ‘From the Alliance of Sahel States to the Confederation of Sahel States’, op. cit. Subsequently, Russia strengthened its military cooperation with ASS in fighting terrorism. Meanwhile, the military bases of France and the United States of America (USA) were closed in the central Sahel.

In as much as the Sahel population encouraged the military authorities of ASS in their efforts toward fighting terrorism, they equally expressed their concern about the compelling security challenges in the Liptako-Gourma region, described as an epicentre of violence. This was done during a consensual national dialogue organised in all central Sahel states. Moreover, the diplomatic incident between Algeria and Mali led to the termination of the 2015 Algiers Accord on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali. This peace deal was replaced by the National Dialogue to Promote Peace and Reconciliation (NDPPR). Unlike, the 2015 Algiers Accord, those labelled as terrorist organisations were not represented during the NDPPR. Among other decisions concluded during the national dialogue were the extension of the transitional period by three more years and granting the military leader the possibility to run for elections.

Dysfunctional democracy

Sahel leaders in the 1990s desired a transition to democracy to improve development and increase the GDP of the Sahel population. To build upon this aspiration, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) encouraged governments to embark on liberalisation policies, privatisation of state-owned companies, and reducing personnel in the public services. Such ambition did not support any form of political violence or military intervention in governance. Sadly, the IMF conditions for African governments further weakened already fragile economies plagued by corruption, embezzlement and high unemployment rates. This situation led to increased protests by the population demanding accountability and led to the eruption of coups from the mid- 1990s to late 2000s. The reoccurrence of coups was mixed with oscillations in and out of democracy with far-reaching effects. The oscillations did not only interrupt the democratisation process in many African countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, but equally reduced the population’s attachment to democracy. This is due to democratic governments proving to be inept at addressing the many problems linked to nation-building in Africa. Thus, militaries usurping power in the 2000s was preceded by popular revolution against those they considered not suitable to providing solutions to local problems.

Added to these factors was the progressive acquaintance of the Sahel population with the internet and social media. This exposure opened them to the world and improved their understanding of governance and neo-colonial issues that negatively affect their countries. The enlightened youth and ambitious Africans of the 2020s embarked on nationalist movements demanding accountability from the government, and equally condemning neo-colonial accords and cooperation such as France-Afrique. This nationalist spirit led to increasing requests to Sahel governments by their populations to withdraw from such cooperations that they described as exploitative. Unfortunately, this request was not acted upon by the democratic governments, and recent Sahel revolutionary leaders exploited this situation to build a degree of credibility with the population. As such, they promised during post-coup media sessions to set their countries free from all forms of foreign interference – military and economic.

Conclusion

Political transition in central Sahel is a complex and generational issue. The region’s history of failed transitions, economic challenges, and security threats has created an environment where democracy is often undermined. Failure by previous democratic governments to safeguard the rule of law, separation of power, and encourage development increased the likelihood of military interference in governance. The current military-led transitions, marked by postponed elections and a focus on security, raise questions about the future of democracy in the region. Since several attempts by the AU and ECOWAS to safeguard a return to constitutional order have been ignored by the military authorities, it reflects a democratic backsliding in the region. Thus, the decline of democracy in the central Sahel suggests that the region may face continued instability and governance challenges in the years to come.

Kellian Mbianda is an advocate of the United Nation 16th sustainable development goal of “Peace, Justice and strong Institutions,” and a postgraduate in International Relations from the University of Buea. Currently, he works in the department of conflict management at Wem’afrika.