- Policy & Practice Brief

Evaluation of the African Union Peace and Security Council: Lessons from 20 years of intervention and recommendations for the future

Executive summary

As the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) marks its 20th anniversary, it is important to reflect on its journey and take stock of the achievements, challenges, and opportunities. In essence, this commemoration provides an opportunity to reimagine the role of the PSC in promoting and consolidating the peace and security agenda on the continent, as well as looking beyond the immediate context. This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) makes use of four variables: relevance, productivity, efficiency, and collaboration, to evaluate the PSC’s 20 years of existence. The PSC’s 20-year history includes both successes and failures. On the positive side, progress has been made to ensure the PSC remains relevant and responsive to the needs of Member States and, ultimately, African citizens. In addition, the PSC in itself has been productive in dealing with peace and security challenges, including unconstitutional changes of government. This progress notwithstanding, challenges abound. Some of the challenges discussed include the PSC’s reactive approach and delayed response to insecurity challenges, the amorphous application of the principle of subsidiarity, and competing national interests. To reimagine the PSC, there is a need for collective action, operationalising the PSC committees and other critical institutions, strengthening the PSC Secretariat, and providing adequate resources.

Introduction

As the African Union Peace and Security Council (AU PSC) marks its 20th anniversary, it is imperative to reflect on the 20-year journey and take stock of the achievements, challenges, and opportunities. In essence, this commemoration provides a unique opportunity to ‘reimagine’ the role of the PSC in promoting and consolidating the peace and security agenda on the continent in the last two decades. The transformation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) to the AU in 2002 heralded a new dawn and marked a significant shift towards a more comprehensive and collective action which gave impetus to the emergence of a more proactive and structured approach to peace, security, and stability on the continent. To this end, and in line with Article 5(2) of the Constitutive Act, the PSC was established in 2004.

The African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) is built around structures, objectives, principles and values, as well as decision-making processes relating to the prevention, management and resolution of crises and conflicts and post-conflict reconstruction and development (PCRD) on the continent. The PSC Protocol, adopted in July 2002 in Durban, South Africa, and entered into force in December 2003, outlines the various components of the APSA and their respective responsibilities. Other documents were subsequently adopted to facilitate and expedite the operationalisation of the APSA. As a standing decision-making body, the PSC is bequeathed with the sole mandate of promoting peace, security and stability. The norms underlying the mandate of the PSC and the methods and instruments for executing its mandate are enunciated in the PSC Protocol.

The PSC, as an integral part of the APSA, is viewed as a major roleplayer in the ‘silencing the guns’ agenda on the continent. Guided by the cardinal responsibilities of promoting human security, respect for borders, and peaceful resolution of conflicts, the PSC has been touted as a beacon of hope that is to deliver the ‘political kingdom’, as envisioned by its founders purpose of this policy brief is to take stock of the PSC. Specifically, the policy brief seeks to answer the following questions: How has the PSC fared in its mandate? What are the challenges that have hampered the PSC’s efforts? How can the PSC be reimagined and strengthen its role and capacities in conflict prevention, management, and resolution? To answer these questions, the brief makes use of an evaluation framework that encompasses four variables – relevance, productivity, efficiency, and collaboration.It augments the discussions with some empirical examples. This, we believe, provides a foundation for a more nuanced and better evaluation of the utility of the PSC in promoting peace, security, and stability.

Overview of the 20-year existence of the AU PSC

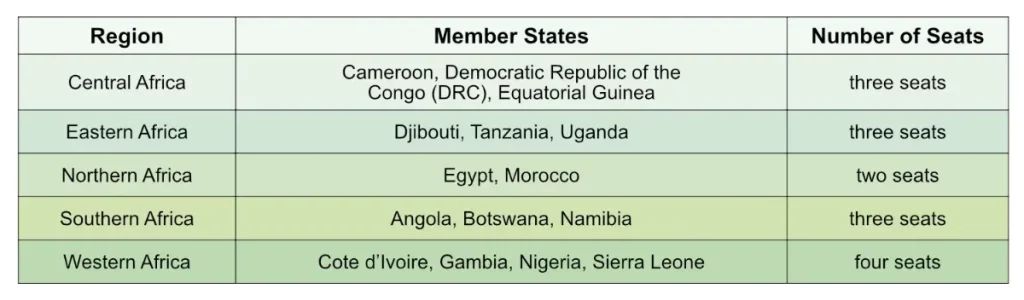

The PSC consists of 15 Member States elected by the Assembly of the Heads of State of the AU. Ten members are elected for a two-year term, while five serve a three-year term. To ensure regional inclusivity, the Council’s composition includes two seats for Northern Africa, three seats for Central, Eastern and Southern Africa, and four seats for West Africa. Being a central component of the APSA, the PSC plays a critical role in serving as the standing decision-making organ on matters relating to the promotion of peace, security, and stability on the continent.

As the decision-making organ, the Council is responsible for anticipating and preventing disputes or conflicts, undertaking peacemaking and peacebuilding functions, authorising the deployment of peace support operations, and recommending intervention in cases of war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide. Article 2(1) of the Protocol defines the PSC as: ‘a collective security and early-warning arrangement to facilitate timely and efficient response to conflict and crisis situations in Africa’. To further its work, the PSC is supported by the AU Panel of the Wise, Continental Early-Warning System (CEWS), African Standby Force (ASF), and Special Fund. Additionally, the PSC plays a vital role in the promotion of democratic principles and institutions, popular participation, and good governance as well as the acceleration of the political and socio-economic integration of the continent.

Relevance of the AU PSC

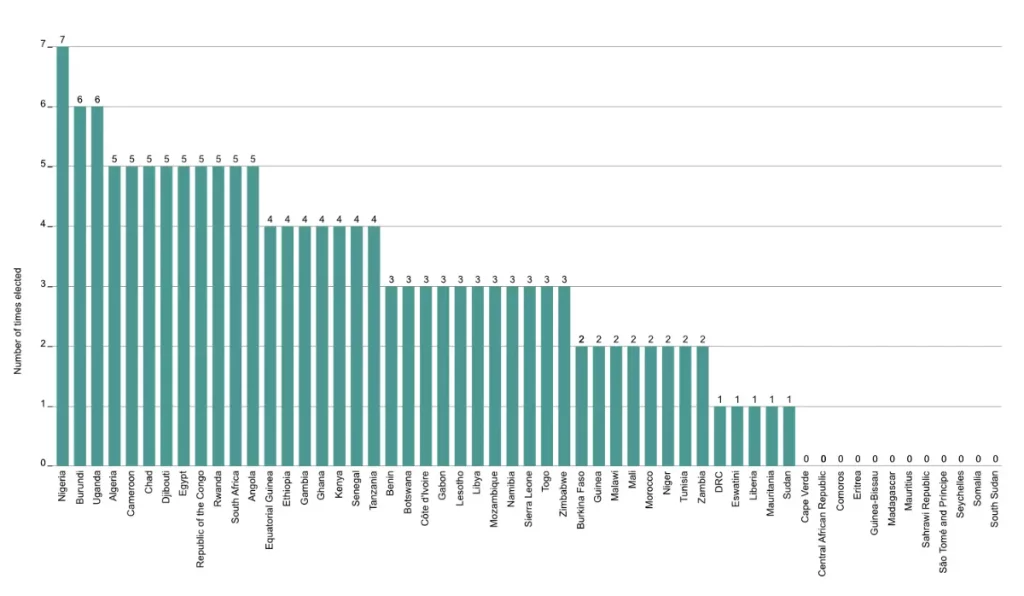

In discussing the relevance of the PSC, this PPB focuses on political will, respect for the PSC’s decisions, the ability of the PSC to attract funding from Member States and to make unprecedented decisions, and the commitment of the Council Members to participate and contribute to the PSC sessions. As regards political will, it is apparent that Member States find the PSC a relevant political institution. Out of the 55 Member States of the AU, 53 (96%) have signed, ratified, and deposited the instrument. Only two countries, Cape Verde and South Sudan, have not ratified and deposited the instrument. The high level of ratification is a testament to the value and commitment that Member States attach to the PSC. Importantly, out of the 55 countries, only 12 have never been elected Members of the PSC, as shown in Figure 1. The high number of Member States elected to the PSC underscores the relevance and value Member States attach to the Council. From Figure 1, it is clear that Nigeria has had unfettered membership to the PSC. This is attributed to the fact that the Western African bloc (with four seats) bequeathed one permanent seat to Nigeria in the PSC, given its economic and political influence in the region, while the other three slots are open for competition.

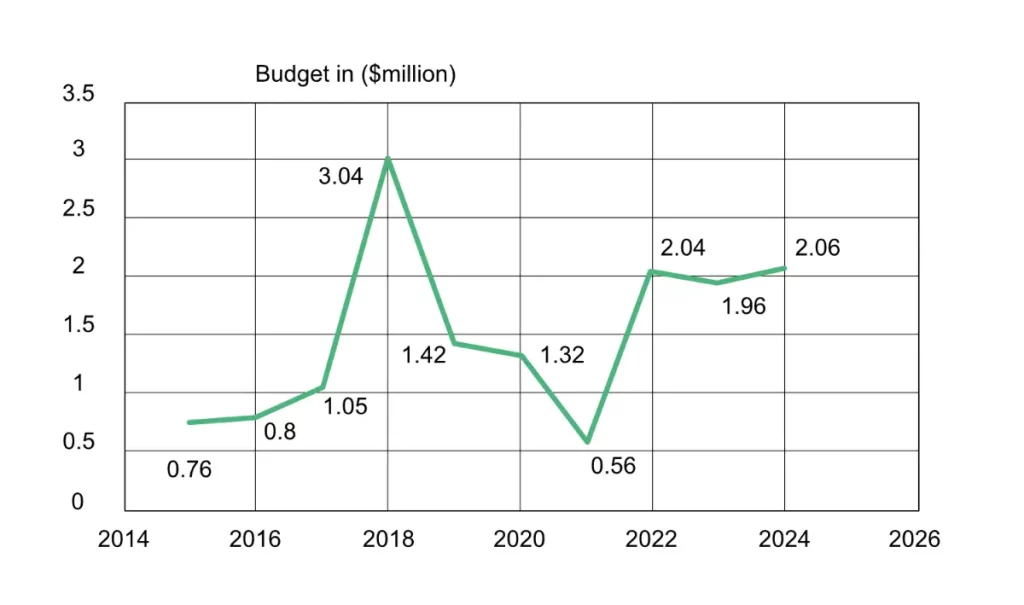

To ensure that the PSC is functional in line with its operational mandate and institutional setup, a Secretariat was established. The establishment of the PSC Secretariat, albeit understaffed, underscores the relevance of the PSC as a major political actor in promoting peace, security, and stability on the continent. With regard to resources, the PSC has continued to attract funding from the Member States, which not only underscores its relevance but has enabled the PSC to conduct its operations uninterrupted. The PSC has held numerous sessions and provided astute policy directives that have been critical in solving some of the peace and security challenges in Africa. Since 2015, the PSC budgetary allocation (see Figure 2) has steadily increased, with a noticeable reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic period. As indicated in Figure 2, the peak in terms of budgetary allocation was recorded in 2018, where the PSC was allocated a sum of US$ 3 036 746. This, however, declined significantly to US$ 561 142 in 2021. The problems of COVID-19 and the economic challenges that manifested thereafter led to a sharp decline in Member States’ contributions to the AU, with a spillover effect on the PSC budgetary allocation.

Evidence from the PSC indicates that Member States are committed and interested in participating in the various sessions. As of 21 May 2024, the PSC has held 1 213 open and closed sessions at ambassadorial, ministerial, head-of-state and government levels. The Council, for its part, has continued to have full representation of 15 Member States for the last 20 years, except in 2020-2021 amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted by Williams, Member States on the PSC agenda (those facing conflict or crises) have continued to have a keen interest in PSC activities with a view of influencing its deliberations and possible outcomes. In terms of decisions, the PSC has continued to render decisions regarding the peace and security landscape. In 2015, for example, the PSC applied its authority by invoking Article 4(h) of the Constitutive Act, which seeks to avert the risk of mass atrocities. In this particular case, the PSC, during its 565th session, authorised the deployment of the African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROB). The proposed mission was to consist of 5 000 personnel. This decision was, however, reversed by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government.

Productivity of the AU PSC

From the statistics (based on the PSC’s 1213 sessions held so far), it can be argued that the PSC has been active and productive in its engagement. Since its establishment in 2004, several successful developments have been recorded. In the context of conflict prevention, the AU PSC has significantly enhanced institutional capacities at continental and regional levels. This includes the operationalisation of the CEWS, dedicated to anticipating and preventing conflicts through the timely collection of data, analysis, and early reporting. This, to some extent, has facilitated early response by the PSC. The PSC has also been instrumental in the operationalisation of the Panel of the Wise, ASF and the Peace Fund, which form critical cogs in the APSA. The operationalisation of the Peace Fund, which can, to a large extent, be credited to the PSC, can be viewed as a milestone towards realising African solutions for African problems. Besides operationalising institutional setups as outlined above, the PSC has been able to tackle, among others, emerging issues such as climate security, cyber security, unconstitutional changes of government, and transnational organised crime. The PSC has also been engaged fervently in collaboration with Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Regional Mechanisms (RMs), Member States, and civil society organisations (CSOs) in conducting priority needs assessments, developing quick-impact projects, and peace-strengthening projects for countries emerging from conflict, with the primary aim of avoiding relapse into conflict in the short term.

Most recently, the AU PSC held its 1 211th session on 15 May 2024 to review the implementation of the Protocol establishing the PSC, article by article. Key recommendations emerged, including the need to address the phenomenon of Member States denying looming conflicts, which hinders the PSC’s intervention abilities; evaluate the financial and administrative capacities of Member States to qualify for PSC membership; enforce sanctions and engage countries under sanctions to return to constitutional order; implement proper benchmarking to enforce the principle of subsidiarity; and allow REC/RMs to participate in PSC agenda-setting and discussions without voting power.

Efficiency of the AU PSC

While the PSC has been effective in terms of holding its sessions and making, in some cases, novel decisions, it has not been effective in following up on the implementation of these decisions. In response to the proliferation of UCGs, the PSC, in line with Article 7(g) of the PSC Protocol, has been efficient and consistent in suspending and applying sanctions. For instance, from 2019 to 2023, the PSC suspended seven Member States: Sudan (June 2019 and October 2021), Mali (August 2020), Guinea (September 2021), Burkina Faso (January 2022), Niger (August 2023), and Gabon (August 2023). Despite the suspension and application of sanctions, the PSC has not followed through to restore constitutional order in these countries. The PSC has also been accused of selective decision-making. While it has invoked its power to sanction or suspend countries, as highlighted above, it has, in some instances, failed to invoke suspension when the need for this may seem rather obvious. In 2021, the AU PSC failed to sanction or suspend Chad for what appeared to be a UCG. During his speech at the 20th anniversary of the PSC in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, AUC Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat averred that:

the PSC accommodated itself in some cases, either by refusing to apply the suspension, when it essentially qualified a change as an Unconstitutional Change of Government or by refusing to apply sanctions when its decisions were violated, particularly, with regard to the prohibition on the perpetrators of Unconstitutional Change from standing as candidates in the elections after the transitional period. And all those who drew attention to it, intellectuals, Civil Society actors or African leaders, were treated as protesters, embittered, calculating people. The incongruity was pushed to its peak, when we observed a Regional Economic Community (REC), chaired by a Member State, suspended by your Distinguished Organ, in the presence of PSC Members.

The inefficiency of the PSC sanctions or suspensions is underscored by the fact that the sanctions imposed upon Guinea, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Sudan, for instance, have not dissuaded the reoccurrence of coups elsewhere nor prevented unlawful military usurpation of power in Niger (August 2023) and Gabon (August 2023). From the above discussion, it is apparent that the PSC’s response has not been efficient in achieving the desired objectives, as it lacked coercive power. As such, ‘this congenital weakness makes the operational function of Council a complete pipe dream’.

Collaboration with other bodies and organs

Article 12(3) of the PSC Protocol underscores the importance of collaboration. The Article notes that the PSC shall also collaborate with the United Nations (UN), its agencies, other relevant international organisations, research centres, academic institutions, and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs). Progress has been made on this front, especially with strong collaboration with the UN Security Council (UNSC), European Union (EU) Political and Security Committee, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on humanitarian issues in the area of conflict prevention, management, and resolution. The recent establishment of the Inter-Regional Knowledge Exchange on Early Warning and Conflict Prevention (I-RECKE) has further augmented collaboration, especially with the RECs.

The AU PSC has made efforts to engage RECs/RMs through technical meetings. In April 2024, for instance, the AU PSC held its inaugural meeting with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Mediation and Security Council. This was the first meeting between the two organs since the establishment of the PSC. A critical review of the AU PSC engagement unearths some fundamental issues. First, it is clear that not all RECs/RMs have organs similar to the AU PSC. In fact, in one of the meetings, it was recommended that all RECs/RMs should establish similar organs to enhance interactions and coordination, especially when it comes to early response. Secondly, while early-warning systems have been developed by the AU and RECs, not all of them are operating at optimum levels. Thirdly, other organs, such as the Panel of the Wise and the ASF, which support the work of the AU PSC, are not evenly developed and operationalised in all RECs/RMs. These structural issues, coupled with institutional weaknesses, have hindered effective collaboration. As regards collaboration with CSOs, it is important to note that although Article 20 of the Peace and Security Protocol envisages close collaboration with CSOs, the PSC engagement with the Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC), for instance, has been limited to the annual CSO forum.

Challenges facing the AU PSC

The 20 years of the AU PSC’s existence include both successes and failures. While progress and successes have been recorded in some quarters, setbacks and challenges still abound. The challenges have impacted the PSC’s ability to executive its mandate effectively and efficiently. These are discussed below.

The PSC’s reactive approach and response delays

One of the significant challenges lies in the persistent recurrence of conflicts across Africa, fuelled by diverse factors, such as political instability, ethnic tensions, socio-economic disparities, and resource competition. The resurgence in political instability and violent conflicts across various regions of Africa, from the recurrent crises in Sudan and the DRC to the situation in the Sahel region and the alarming recurrence of military coups in West Africa, reveal significant limitations of the PSC’s efficacy in conflict prevention. At the heart of these issues lies the fact that the PSC’s interventionist approach has been predominately reactive, responding to crises as they unfold rather than proactively preventing them from taking place. This reactive nature is a consequence of the absence of a well-established culture of proactive conflict prevention within the broader AU ecosystem. It has been remarked that the slow response of the AU PSC makes it look like a ‘toothless bulldog’. The failure of the PSC to address the reoccurrence of coups d’état in the last three years in Burkina Faso (2022), Niger (2023), Mali (2020 and 2021), Guinea (2021), Gabon (2023), and Sudan (2021) gives credence to the above assertion.

Secondly, the PSC has grappled with persistent gaps in early warning and early action, hindering its ability to address emerging security threats proactively. Despite the existence of the CEWS, which aims to ‘anticipate and prevent conflicts on the continent’ and report to the Council, the practical implementation of the outcomes of this system has been fraught with limitations. Member States have often been reluctant to acknowledge and respond to looming crises and conflict situations despite receiving early-warning information. They usually invoke the principle of sovereignty to resist or delay action based on early-warning reports, as they prioritise their own national interests. Consequently, the reluctance of Member States has compelled the PSC to be reactive rather than proactive in crisis management. This situation raises questions about the credibility and powers of the PSC in implementing its mandate as well as Article 7(e) of the Protocol, which authorises the Council to intervene on behalf of the AU in a Member State in the case of grave circumstances, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Operationalising subsidiary committees

The PSC Protocol delineates the creation of subsidiary bodies, including ad hoc committees for mediation, conciliation, or inquiry, comprising individual states or groups of states. In accordance with this, the Council has instituted the Military Staff Committee (MSC) and the Committee of Experts (CE) to strengthen its operations. The MSC is composed of defence personnel tasked with providing military and security advice, while the CE comprises 15 experts, each representing a PSC Member State, along with support staff from the PSC Secretariat, aiding in the drafting of technical documents and PSC decisions. Despite the CE being operational since December 2017, questions linger regarding its full operational capacity. The efficacy of these committees is critical for the success of the PSC. However, institutional constraints within the AUC pose formidable challenges. The scarcity of human resources has detrimentally impacted the functioning of both the MSC and the CE. The MSC’s inability to achieve full functionality mainly stems from inadequate standby force representation among sitting PSC members based in Addis Ababa. Similarly, the CE, particularly the PSC Secretariat, grapples with understaffing and an overwhelming workload. Given the pivotal role of the PSC Secretariat in supporting the PSC, limited staffing often results in delays, reduced capacity for crisis responses, and constraints in conducting comprehensive analysis and research to inform policy recommendations and interventions.

Competing interests among Member States

The PSC has also encountered formidable obstacles in its mission to foster peace, security, and stability across the continent, largely due to the divergence of interests among Member States. The competing interests of States within the Council have, in some cases, complicated decision-making, thus delaying early action. Taking care of States’ interests, on the one hand, and executing its mandate as a supranational institution, on the other, has complicated its role in some situations. These conflicting interests, often grounded in disparate national priorities, geopolitical strategies, and strategic partnerships, have hindered the Council’s ability to forge consensus or take decisive action during crises. A noteworthy example is the Libyan crisis of 2011. Initially, the AU condemned the Libyan government’s violent crackdown on protests and proposed a high-level committee for mediation. However, when the UNSC authorised military intervention through the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), despite the AU’s rejection, certain African states supported the military intervention, undermining the AU’s position. As noted by the AU Chairperson during the High-Level 20th Anniversary Colloquium of the PSC, ‘the notorious lack of inter-African solidarity has left Member States beset by insoluble demands for peace and security with no way out’.

Ambiguity of the principle of subsidiarity

The concept of subsidiarity, which was initially popularised by EU law, found space in the APSA discourse. It is founded on the idea that long-term peace and security are best achieved when conflict management and resolution mechanisms are led or driven by actors (read RECs) who are affected or closer to the theatre of conflict. In other words, RECs are best placed to respond to conflicts within their spheres of influence because they have what can be called proximity advantage. The application of the concept in the APSA remains ambiguous. The AU legal framework has entrenched the ambiguity, as it recognises the pre-eminence of both the AU and the RECs in matters of peace and security. This, in essence, makes Africa’s multi-layered security architecture even more complex, as it creates another layer of responsibility (in this case, the RECs) between the Member States and the AU. To make matters worse, the AU protocol and the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the AU and RECs neither define nor operationalise the concept of subsidiarity. The concept also ‘assumes shared competency between the AU and the RECs which in reality does not exist’. These complexities have led to an antagonistic relationship between the AU and the RECs. In some cases, the decision of the PSC has been ignored or undermined under the pretext of implementing the principle of subsidiarity. Some Member States have exploited this lacuna and circumvented the decisions of the PSC through the RECs. This begs the question of which decision has primacy and why there is a contradiction in the application of the concept. In addition, it raises the question of which institution should submit to the other in this case and which decision takes precedence. As noted by the AU Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat:

The distortion of the concept of subsidiarity has worsened the problem. This overused concept has suffered a strange and very worrying fate. Instead of being the basis on which a dynamic, fruitful, and supportive complementarity rests, it has become the doctrinal support for a belittling of continental bodies, promoted by the apparent or hidden supporters of the abandonment of the principles and decisions of the continental organisation. In this way, subsidiarity has become the main ideological referent to trivialise, indeed, downright paralyse, the main Organ of the entire AU Peace and Security Architecture.

Policy recommendations

It goes without saying that the AU PSC remains an important actor in the APSA. As it celebrates its 20th anniversary, there is a need to re-examine and revamp the PSC and make it more efficient, effective, and responsive to the emerging peace and security challenges on the continent. To assist in this transformation, the following recommendations are proffered:

- There is a need for the PSC to strengthen its preventive mandate. This can be achieved through frequent engagement with the CEWS and the early-warning systems of the RECs. Regular joint briefings by the AU and RECs to the PSC will contribute immensely to conflict prevention. The PSC should push for the adoption of the Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment (SVRA) and the Country Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment methodologies as a conflict prevention approach. As things stand, the PSC seems reactionary by employing a ‘firefighting’ approach to weighty peace and security issues.

- Resolve the ambiguity regarding the principle of subsidiarity. The new Protocol and the MoU governing the relations between the AU and RECs have elevated the relationship at the level of decision-making bodies through the institutionalisation of the Mid-Year Coordination Meeting. According to the Protocol, which also addresses the issue of peace, security, and governance, RECs/RMs have the right to participate fully in both the agenda-setting and the deliberations. Operationalising these aspects will be important in promoting Africa’s peace and security agenda. The ongoing operationalisation of the APSA and the African Governance Architecture could be well implemented through this channel.

- There is a need for the PSC members to promote the African agenda with zeal and zest, rather than promoting their national interests. Related to this, is the need for the PSC to move away from the principle of compromise in decision-making on some issues. In some instances, the PSC could put contentious issues to a vote, rather than subjecting them to consensus or compromise, which results in diluted decisions and makes them vague and difficult to implement. The current practice of reaching agreement by consensus has hampered the ability of the PSC to make some critical and timely decisions.

- While the PSC agreed, in 2019, to establish a team as a focal point comprising representatives from the AU and the RECs to foster coordination on peace and security, there is a need to operationalise this framework. This will be accompanied by holding joint field missions and joint retreats or brainstorming sessions for coordinated and strategic response. Regular engagement between the PSC, RECs, and CSOs will be a positive step. As alluded to above, the inaugural joint consultation between the AU PSC and ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council, held at the ambassadorial level on 24 April 2024 in Nigeria, is commendable and should be replicated with other RECs. In essence, there is a need for a paradigm shift in the intercourse between the AU PSC and the RECs.

- There is a need to fully operationalise the Committees and other institutional frameworks, such as the Standby Force and Rapid Intervention Brigade, to assist the PSC in achieving its mandate. In addition, there is a need to strengthen the PSC Secretariat by providing regular training and onboarding of technical staff with high-level expertise to support the work of the PSC.

- Strengthen engagement with CSOs, as envisaged in Article 20 of the Protocol. Regular meetings and briefings with the ECOSOCC will bridge the existing gaps. The ECOSOCC needs to be strategic to actualise this provision. They should further engage with citizens, especially those in the conflict theatres. They should, in essence, move from Addis to the conflict zones.

- Finally, there is a need for Member States to provide adequate finances to support the operationalisation and activities of the PSC. This will ensure that the PSC delivers on its mandate.

Authors

Oita Etyang (ORCiD: 0000-0001-9014-5032) holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Johannesburg (RSA). Dr Etyang has over a decade of experience across Africa, covering the wider spectrum of conflict prevention, management, resolution and post-conflict reconstruction processes.

Taye Abdulkadir joined the AU Continental Early Warning System (CEWS) in July 2009. As a senior technical staff member, he played a major role in the conceptualisation and operationalisation of the technical aspects of CEWS tools and processes, both at the AU and the RECs/RMs. Taye has been working in the areas of conflict prevention, early warning, and youth for peace for more than 19 years.

Claudia Masah (ORCiD: 0009-0008-8446-7500) is a programme development expert with an interest in the areas of Peace and Security in Africa. She has five years of experience in research and youth engagement in relation to conflict prevention.

Tatenda Mapiro is an International Development practitioner committed to advancing peace, security, and stability in Africa. With four years of experience in programme design and implementation, she focuses on conflict prevention and civil society engagement to promote peace and security across the continent.