- Policy & Practice Brief

A historical overview of coalition governments in the province of KwaZulu-Natal

Introduction

This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) is situated within the broader context of the rise of coalition politics in South Africa, in particular at the local government level. For instance, in 2021, the local government elections (LGEs) produced 70 hung local municipalities17That is, municipalities with no outright majority (50% plus 1%)., a 159% increase compared to the 2016 LGEs, which had produced only 27. Furthermore, metropolitan municipalities in the country, particularly in the Gauteng province, were governed by coalitions in 2016 and 2021. These developments in the political landscape of the country increased public, media and academic attention to the legal, political and governance management of coalitions and ignited conversations about the extent to which coalitions are sustainable, stable and viable forms of government. The decline in electoral support for the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), and the proliferation of new political parties has had much to do with the increase in coalitions. These factors are indicative of a changing political landscape from a dominant party rule towards a more multi-party rule, which calls for political parties to mainstream power-sharing mechanisms for effective co-governance.

Some of the views of scholars, the mainstream media, and some political party leaders on coalitions in South Africa have painted this form of governance as unstable and dysfunctional. For instance, speaking at the ANC’s January 8 Statement held in Mpumalanga on 13 January 2024, President Cyril Ramaphosa stated that “the frustrating experience that we have had with dysfunctional coalition governments has shown that these coalitions really don’t work for our people”, and that “replicating this bitter experience of total chaos, instability and dysfunctionality at a national and provincial level will be a total disaster for our country.”18Cotterell, G. 2024. Ramaphosa warns ANC supporters about ‘dysfunctional’ coalition governments. The Citizen, 13 January. Available from: https://www.citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/politics/ramaphosa-warns-anc-supporters-coalition-governments [accessed 19 April 2024].

There are three challenges to these views and narratives. Firstly, they are not objective. Secondly, in their lack of objectivity, there is insufficient recognition of the relatively successful history of coalitions in the country. Thirdly, they are based on a select few and mostly metropolitan municipalities. In the first challenge of objectivity, there is a lack, or insufficient recognition, of the positive side of the coalition coin, which will be discussed in this PPB. In the second instance, linked to the first, there is insufficient acknowledgement of the historical existence and experience of stable coalition governments in the country before the 2016 LGEs. In the third instance, the focus is on Category A municipalities (larger, metropolitan municipalities) mainly in Gauteng, while there is underreporting and a lack of research on coalitions in Category B (other smaller municipalities) and other provinces that may have stable coalitions.

Indeed, there are many examples of politically unstable and administratively dysfunctional coalitions at the local level. However, research shows that this is not the case for the majority of local government coalitions. The South African Local Government Association (SALGA) once stated that of the 82 local government coalitions (including district and local municipalities) formed after the 2021 LGEs, only 32 are politically unstable. The converse perspective is that 50 of the 82 are, in fact, politically stable. Thus, views and narratives around coalition governments in the country need to become more objective and nuanced. In other words, in addition to coalitions being dysfunctional and politically unstable19Joel, L. 2024. Are coalition agreements good for South Africa? SABC News Unfiltered. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DXsW-CkXfiI [accessed 22 April 2024]. in some municipalities, they have also historically been successful in mitigating conflict and fostering political stability through power-sharing – both nationally and provincially.

This PPB aims to provide a more nuanced view of the phenomenon of coalitions in South Africa, with a specific focus on the province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN). The PPB draws on historical and contemporary experiences of coalition governments in KZN at the provincial and local levels to highlight some successes of this form of governance in the province. The PPB will further provide recommendations from experiences in KZN with coalitions and others that can be beneficial for sustainable coalitions in the context of the 2024 national and provincial elections (NPEs) and connected to the 2026 LGEs.

From Political Violence to Power-Sharing

It is prudent to highlight at the onset that coalitions in South Africa are not a new phenomenon and that the very first form of government in the country’s democratic dispensation was a type of coalition government. Following the 1994 NPEs, South Africa formed a Government of National Unity (GNU) between the ANC, National Party (NP) and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). Under normal circumstances, a coalition government is formed when no political party contesting elections obtains an outright majority of the votes in order to govern. However, even though the ANC received an overwhelming majority of 62.65% of the electoral votes, the interim Constitution mandated a GNU entitling political parties holding at least 20 seats in the National Assembly to at least one Cabinet portfolio.20Interim Constitution of South Africa, 1993, Section 88(2). Available from: https://www.peaceagreements.org/viewmasterdocument/407 [accessed 17 April 2024].

A GNU generally arises out of a particular context to address a particular phenomenon, in this case political conflict. Beukes notes, “GNUs are often negotiated in countries that experienced conflict in the recent past that led to sharp divisions along racial, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious lines”.21Beukes, J. 2021. Hung Councils in South Africa: Law and Practice. Bellville: The Dullah Omar Institute, University of the Western Cape, p. 14. This was the nature of the South Africa 1994 GNU, which was preceded by a negotiation process referred to as the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). CODESA brought different political actors under one roof to begin a process of negotiating a new government.

The GNU was a product of the CODESA negotiations, which ultimately formed part of the interim Constitution of 1993. The GNU was strategic in ensuring that political actors were brought on board in charting a new path towards reconciliation and nation-building. The GNU was used as a conflict-mitigating tool to ensure that there was no resurgence in political conflict from those who would eventually resist the new dawn. Beukes states, “Before South Africa transitioned to a democracy, the country experienced conflict and violence stemming from apartheid which caused deep divisions among contending race groups”.22Ibid Although the ANC had no political obligation to share power with the former incumbents, this compromise and resultant GNU mandated by the interim Constitution prevented and mitigated potential conflict post 1994.

The GNU illustrates the positive potential of coalitions as tools that can contribute to political stability for several reasons. Firstly, it was a power-sharing arrangement meant to oversee the process and finalisation of the new Constitution, as per the agreement of the CODESA negotiations. Secondly, it promoted and maintained amicable relations between key political actors, in particular, the ANC, IFP and the NP, who were and could have continued to be in conflict. Thirdly, it served as a type of conflict-mitigation mechanism to deal with political violence nationally and particularly in the KZN province.

Provincial Government Coalitions in KZN

The GNU was also applied provincially in KZN in 1994 between the IFP and ANC. Historically, the IFP was the dominant party dating back to the 1970s and up to the 1990s in KZN, with strong constituencies in rural areas. According to Beall and Ngonyama, the ANC and the IFP had many years of political contestation and hostility towards each other, resulting in political violence since the mid-1980s.23Beall, J. and Ngonyama, M. 2009. Indigenous institutions, traditional leaders and elite coalitions for development: The case of Greater Durban, South Africa. Working Paper no. 55, p. 11. In view of this history, the parties entered into what can be termed a Government Provincial Unity (GPU) in 1994, led by the IFP, but including ANC representatives in executive positions. In this election, the IFP obtained 50.61% of the provincial vote and 41 of 81 seats in the provincial legislature, while the ANC received 32% and 26 seats. This GPU between the two parties created opportunities to mitigate historical conflicts and political violence in the province in the democratic dispensation.

After the 1999 NPEs, the ANC and IFP entered into a grand coalition, as no party had obtained an outright majority. It is noteworthy that the 1996 final Constitution had come into effect and did not provide for a GNU. The IFP received 41.90% of the vote (34 of 80 seats), and the ANC received 39.38% of the vote (32 of 80 seats). Despite the history of violent political conflict between the two parties, this coalition is said to have been politically stable and coherent for the entire five-year term.24Mnguni, L. 2021. Chapter 15: Power transition in KwaZulu-Natal: Post-1994 coalitions in action. In: Marriages of Inconvenience: The Politics of Coalitions in South Africa, p. 420. The provincial coalition government was headed by IFP’s Lionel Mtshali as premier, with Members of the Executive Council (MECs) from the ANC and IFP. The coalition was characterised by great political stability from its inception in 1999 up to 2004, including due to the fact that none of the premiers were voted out of power before the conclusion of their term. The African Independent Congress (AIC), in their presentation during the National Dialogue on Coalition Governments, provided possible reasons why there was no single no-confidence motion against the premier:

“Was this partly because the ANC and the IFP had a pre-election coalition agreement in KZN; was it because the ANC could not muscle out the IFP because [the] other two fringe parties in the KZN legislature had a combined 10 per cent electoral support – not enough to assist the ANC to form a government; or was it because of the values these parties held? With these speculations, we are led to believe that a variation of these factors could have played a role.”25Arnolds, M. 2023. Coalition Framework. Available from: https://www.cogta.gov.za/index.php/docs/aic-coalition-framework-scheme [accessed 22 April 2024].

Ultimately, the KZN coalitions contributed to political stability, tolerance, and de-escalating the political violence that characterised the 1990s.26Mnguni, L. 2021. Chapter 15. op. cit., p. 420. The 2004 NPEs represented a crucial test for the political stability of the province and the IFP-ANC grand coalition government because there was a shift in power dynamics. For the first time, the ANC obtained the majority with 46.98% of the provincial vote and 38 seats in the KZN provincial legislature, while the IFP obtained 36.83% and 30 of the 80 seats available. Despite the changing political power dynamics, the ANC-led provincial government featured two IFP members. 27Ibid, p. 432This coalition arrangement assisted in ushering in a fairly peaceful transition in leadership from the IFP to the ANC and maintained political stability in the province. The ANC-IFP alliance lasted for 12 years until November 2006, following the removal of all IFP MECs from the government. Despite this, the KZN government maintained political stability in the province.

Local Government Coalitions in KZN

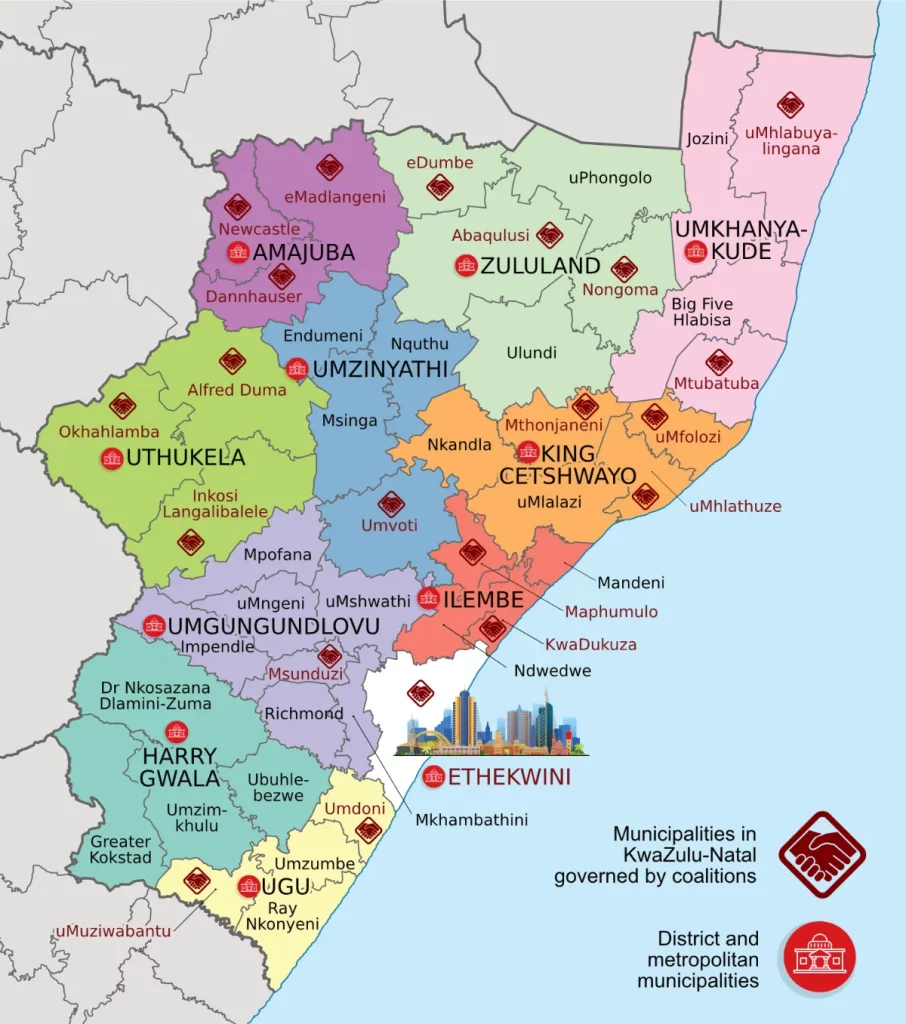

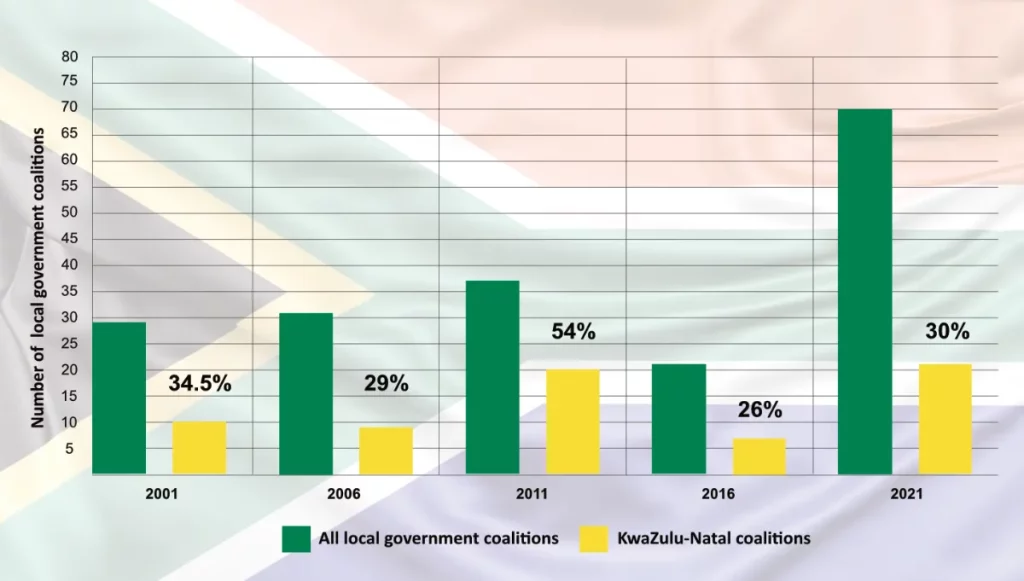

As mentioned before, the 2021 LGEs resulted in a total of 70 hung local municipalities and the formation of 70 coalition governments. Of the 70 municipalities, 21 are located in KZN, which means that 30% of local government coalitions were in KZN, the largest contributor across all provinces. KZN has a total of 44 local municipalities, which means that 47% of the local municipalities are governed by a coalition (21 of 44). Hence, KZN is a key constituency when analysing coalitions in the country – contrary, for instance, to the dominant focus on Gauteng coalitions. In fact, KZN (along with the Western Cape province) has consistently accounted for the majority of coalitions at local government level from 2000–2016, as shown in Figure 1 below. Local coalitions existed in 29 councils in 2000/1; 31 councils in 2006; 37 in 2011; and 27 in 2016. It is noteworthy that of the 29 local municipal coalitions in 2000/1, 10 were in KZN (and 14 in the Western Cape), as the political landscape in these provinces was highly contested. In 2006, there were nine coalitions in KZN out of a total of 31 nationally; in 2011, KZN had 19 out of 37 nationally; and in 2016, there were seven coalitions in KZN out of 27 nationally.28Results according to the Independent Electoral Commission available at: Available from: https://results.elections.org.za/dashboards/lge [accessed 22 October 2023].

Photo Credit: pablographix

Despite this significant history of local municipal coalitions in the KZN province since 2000/1, literature on coalitions in this province is minimal. The 21 local government municipalities that are currently governed by coalitions in KZN are:

- Alfred Duma Local Municipality

- Abaqulusi Local Municipality

- City of eThewkini

- Dannhauser Local Municipality

- eDumbe Local Municipality

- eMadlangeni Local Municipality

- Inkosi Langalibalele Local Municipality

- KwaDukuza Local Municipality

- Maphumulu Local Municipality

- Mtubatuba Local Municipality

- Mthonjani Local Municipality

- Newcastle Local Municipality

- Nongoma Local Municipality

- Okhahlamba Local Municipality

- uMdoni Local Municipality

- uMfolozi Local Municipality,

- uMhlabuyalingana Local Municipality

- uMhlathuze Local Municipality

- uMsunduzi Local Municipality

- uMuziwabantu Local Municipality

- uMvoti Local Municipality

It is noteworthy that the majority of these municipalities have had very limited changes in the mayors and speakers. This is particularly the case in smaller municipalities where there are fewer parties in the council and fewer coalition partners forming government. Also noteworthy is that according to provincial legislation, the executive mayoral system is outlawed, and all municipalities utilise the executive mayoral committee system. More on this will be discussed below in the recommendations section of this PPB.

The large scale of local government coalitions in KZN needs focused attention, considering the province’s historical and contemporary political violence. In contemporary times, the province has been a cause for concern due to heightened political contestation in the context of continuous politically motivated assassinations29Moerane Commission of Enquiry. 2018. Report of the Moerane Commission of Enquiry into the Underlying Causes of the Murder of Politicians in KwaZulu-Natal. Available from: http://www.kznonline.gov.za/images/Downloads/Publications MOERANE %20COMMISSION%20OF%20INQUIRY%20REPORT.pdf of political leaders, especially since the 2021 LGEs.

Photo Credit: AIHS

Recommendations: Bridging Theory and Practice

A careful reading of South Africa’s electoral laws and system in the national, provincial, and local spheres of government reveals an intention to accommodate a plurality of political representatives in government. For instance, the electoral system includes both First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) components to cater for inclusivity and co-governance. The addition of a PR component to complement the FPTP system sought to encourage multiple parties to contest and increased the possibility of holding public office. However, due to voter choices, the country witnessed a consistent and strong electoral showing by the ANC across the three levels of government.

Recent LGEs have shown a shift in voter behaviour, with the ANC obtaining 45.59% of votes across all municipality results combined (the first time the party dipped below 50%). Specific to KZN, in 2021 the ANC received 41.44% of all LGE votes in the province combined; hence, all role players (i.e., government, Parliament, and political parties) need to adjust to this reality in practice to prevent a conflictual and possibly violent intersection of coalitions, and political contestations in the province. This section provides some recommendations that can contribute towards more sustainable coalitions in the province, considering its context.

1. Legislative Reforms

There is a need for legislative reforms to mitigate certain difficulties with coalitions. There have been multiple recommendations to this effect. However, this PPB focuses on some key lessons and recommendations that can be derived from the KZN context.

A key lesson from the KZN context is that all municipalities in the province use the executive mayoral committee system as opposed to the executive mayoral system. The key difference between the two systems is that in the executive mayoral system, the mayor appoints the mayoral committee, and the entire mayoral committee is dissolved when the mayor is voted out of office. However, in the executive mayoral committee system, the municipal council elects the mayoral committee, and it remains even when the mayor leaves.30My Vote Counts. 2024. Positions on proposals to strengthen coalition government in South Africa. Position Paper. Available from: https://myvotecounts.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/MVC-Coalitions-2024.pdf While approximately half of municipalities in the country use the executive mayoral system, the executive mayoral committee system appears to provide greater political stability in the case of coalitions wherein the mayor changes less frequently. As such, the provincial legislature of KZN outlawed the use of the executive mayoral system, and all the local councils in the province use the executive mayoral committee system. This arguably accounts for the relative political stability in the local-level coalition governments in the province, as most coalition councils have had no changes in the mayor and speaker within the current electoral cycle (since the 2021 LGEs). Other provinces wherein the executive mayoral system is used can follow this example for greater stability in local government coalitions.

Another lesson from KZN’s history of provincial coalitions indicates a great deal of political stability when there are fewer parties involved in a coalition government. One can further argue that a grand coalition produces great stability, even in cases where the two largest parties are fierce rivals, as was the case for the ANC-IFP provincial coalition.

Furthermore, we learn from the ANC-IFP provincial coalition that it is important that the party with the most votes leads the coalition and heads the government, for instance, by holding the mayoral position in the local government context. This brings about the most legitimate representation of the will of the voters. Cases such as those in the Johannesburg metropolitan municipal council, where the mayoral position is occupied by a minority party, need to be discouraged. In the Kingdom of Lesotho (Lesotho), a party with the majority of votes/seats in the legislature after the elections receives preference for the Prime Minister position and is bestowed the responsibility of initiating the facilitation of coalition talks with other political parties. This is not the case in South Africa. Once there is no outright winner, it is incumbent upon each and every political party to solicit support from various parties to enter into a coalition and co-govern. Hence, this has motivated the view that the political party which has received most of the votes in the election should be given preference to lead the coalition and occupy prominent positions.31SABC News. 2023. Contribution of the African National Congress (ANC) at the National Dialogue on Coalition Governments in South Africa, Cape Town, 4–5 August 2023. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtLGT-RPkGM&ab_channel=SABCNews [accessed

25 April 2024]. While there is no consensus on the extent of all these legislative reforms, it can be agreed that such reforms are a matter of urgency as there are major ramifications for political stability.

2. Inter and Intra-Party Conflict Resolution Capabilities

Views that paint coalitions in South Africa as unstable are motivated by the political instability that results from the inability of parties to resolve conflicts effectively. Disputes between coalition partners are left unresolved, which leads to the breakdown in coalition governments and the frequent change in mayors, speakers and mayoral committees. There is a need for comprehensive conflict resolution capabilities that can prevent and mitigate conflicts that impact governance. When we consider the province’s history of political violence and the contemporary resurgence in politically motivated assassinations of local officials, conflict resolution becomes even more critical. As the journey towards more coalitions continues, there would be a need for a regulated process, which may include several options, such as officially registering a coalition with an election management body or political party regulatory body and/or submitting agreement documents prior to elections. These must be written, legally binding agreements between political parties, whether they are deposited prior to or after the elections.

Lessons from Kenya are of particular relevance to South Africa, considering similar histories of political violence in both contexts. Following the post-election violence of 2007/08 in Kenya, the country established a dispute resolution mechanism to assist political parties to resolve inter-party and intra-party disputes through a Political Parties Dispute Tribunal.32Mutubwa, W.A., and Kamathi, R., 2022, “The Law and Emerging Jurisprudence on the Jurisdiction of Political Parties Dispute Tribunal (PPDT) of Keny”, Journal of Conflict Management & Sustainable Development, 8(4), Available from: https://journalofcmsd.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ The-Law-and-Emerging-Jurisprudence-on-the-Jurisdiction-of-Political-Parties-Dispute-Tribunal-of-Kenya.pdf [accessed 25 April 2024]. South Africa can adopt a similar dispute resolution mechanism to assist in managing coalition agreements and disputes.

Conclusion

While dominant narratives seem to paint coalition governments as dysfunctional and unstable, this PPB has indicated that there are positive elements to coalition governments from a conflict resolution perspective. Using the province of KZN as an example, coalitions can be viewed as instruments of peacebuilding and political stability. However, to leverage the advantages of coalitions in South Africa, certain requirements need to be met. Among others, there is a need to consider the most appropriate way to enact necessary legislation and incorporate conflict resolution capabilities into the coalition architecture of the country. This will assist multiple parties in working more collaboratively and give effect to constructive co-governance that takes advantage of the diversity of actors.

Authors

Nkanyiso Simelane is a Researcher within ACCORD’s Research Unit, focussing on coalition governments in Africa.

Boikanyo Nkwatle is a Research Intern within ACCORD’s Research Unit, focussing on coalition governments in Africa.