Introduction

Conflict refers to actual or perceived incompatibility of interests, goals, and actions in relationships between individuals or groups. It is a dynamic process where attitudes, behaviours, contexts and structures are constantly changing and influencing one another.1Jacoby, Tim (2008) Understanding conflict and violence: Theoretical and interdisciplinary approaches. Routledge: New York. Conflict in pastoral areas has long been linked to the need to gain control of scarce and strategic resources, particularly water and pasture. However, the key issues here are not merely scarcity, which, as highlighted above, has always been a determining feature of life in the rangelands, but also the increased inability to manage scarcity.2Pavanello, Sara and Levine, Simon (2011) ‘Rules of the range: natural resources management in Kenya-Ethiopia border areas’, Working paper, ODI. In the Horn of Africa, there are common factors contributing to conflict and violence within and between pastoralists, such as inappropriate government policies, socio-economic and political marginalisation, inadequate land tenure policies, insecurity, intensified cattle rustling, proliferation of small arms and light weapons, weakened traditional governance in pastoral areas, vulnerability to climatic variability, and competition with wildlife.3IGAD (2022) ‘Conflict dynamics in IGAD Region: Drought and other Hazards’, IGAD Drought Disaster Resilience and Sustainability Initiative (IDDRSI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20–22 July.

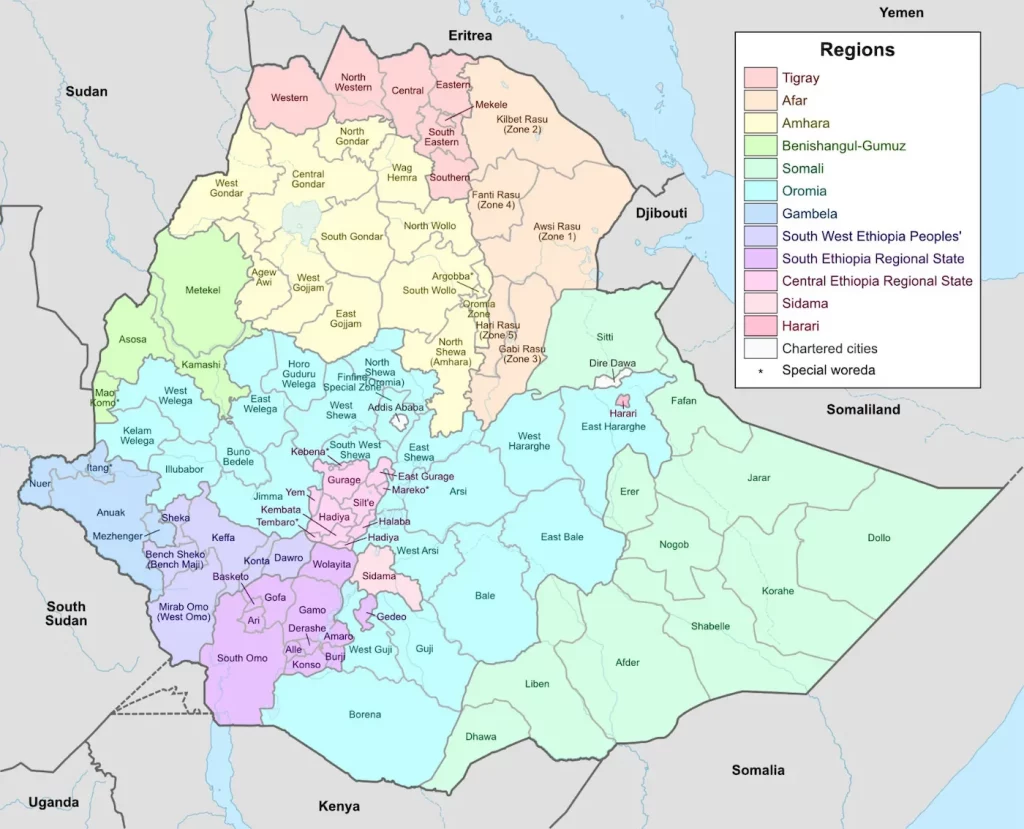

In Ethiopia, the pattern and forms of the recent violent conflicts in pastoral areas indicate that they have been involved in resource control and utilisation competition.4EU Emergecy Trust Fund for Africa (2016) ‘Cross-border Analysis and Mapping Final Report’, 22 September. Conflicts are a common phenomenon in the South Omo Zone pastoralist and agro-pastoral communities due mainly to resource competition (pasture and water-points) and negative perceptions.5Shetahun, Asmare (2023) ‘Cross-Border Conflict Peacebuilding Practices of Dassanech, Nyangatom and Hammer Community of Ethiopia and Turkana of Kenya’, Journal of African Conflicts and Peace Studies, 5(2), Available at: <https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jacaps/vol5/iss2/12> [Date accessed: 30 January, 2024]. However, conflict, by its nature, is dynamic; the drivers or causes and their nature are changeable through time due to many natural and human-made phenomena. Accordingly, an in-depth investigation of natural resource-based conflict and its dynamics in the South Omo Zone in Ethiopia is the focus of this article. This article is based on a study conducted in the Dassanech, Hammer and Nyangatom Woreda collective pastoralist community, and based on empirical primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews, document analysis and focus group discussion (FGD).

Discussions and findings

The sources of conflict

Conflict is the result of internal resource scarcity, shortage and competition for use in the Nyangatom, Dassanech and Hammer community of South Omo, Ethiopia. Violent conflicts are caused by struggles over access to and ownership of land, water or other renewable natural resources. Controlling access to resources, and thereby denying access to others, is often a cause of local conflicts. The conflicts between the Turkana community and the Dassanech, Hammer and Nyangatom community are principally caused by competition over resources like water and pasture, livestock raiding, and disagreements over boundary demarcations.

Animal raiding and conflict

Among East African pastoral communities, livestock raiding has been a common traditional practice.6IGAD (2022) op. cit. In the Nyangatom, Dassanech and Hammer community, the participants in animal raiding are members of agro-pastoral ethnic groups and pastoral communities living there and in the neighbouring Kenyan community. Raided animals are sometimes returned to the rightful owners through the help of security forces of the government and elders through negotiations and reconciliations. According to FGD participants and key interview informants, mobilised non-pastoral individuals from the Kenyan side of the border area engaged in livestock raiding of the Ethiopian pastoralist and agro-pastoralists. Livestock raiding is done for economic purposes to get money from selling the cattle or their meat.

Land claims and conflict in the study area

There are also grievances around the absence of compensation for loss of land for government projects and private commercial agriculture and grievances over access to water and pasture. These grievances created new drivers of conflict. The resource competition often takes the form of protecting livelihood security and ethnic conflict, with groups organised around narratives of land attachment based on ethnicity. In the study area, various unresolved historical land claims and grievances are the structural cause of violent conflicts between ethnic groups. Territorial land claims are the catalyst of the protracted conflict in the study area. The conflicts related to land claims remain unresolved.

Fishing rights and conflict

There is conflict in the Dassanech-Turkana area over access to fish products from the natural lake. According to key informants and FGD participants, the fish are highly concentrated in the northern tip of Lake Turkana, where the Omo River enters the lake. The high quantity of fish in the area attracted Kenyan fishermen using modern motorboats armed with machine guns. The Ethiopian fishermen use light motorboats and wooden canoes equipped with light weapons for self-protection. The fishermen are part of the conflict, as they intend to control the fishing area. The Dassanech Woreda are also facing competition for fisheries in Lake Turkana from Ethiopians who have official business licenses to engage in fishing for a living. In the past, the Dassanech ethnic group depended on livestock production and crop cultivation and occasionally, they fished for food and as a source of income. Due to this, there was no competition in fishing. However, as a result of the loss of income from livestock and crop production, the Dassanech have resorted to fishing. This has increased the competition for fishing business. The Dassanech claims rights to control the area and the fish resources. The power imbalance between fishers of the two countries needs intervention to reduce the probability of violence.

Water-point conflict

The provision of water supplies in Ethiopia is among the lowest in Africa. The strong bias toward urban development historically meant that the provision of water supplies in rural areas is particularly low.7Flintan, F. and Tamrat, Imeru (2002) ‘Spilling Blood Over Water? The Case of Ethiopia’, in J. Lind & K. Sturman (Eds), Scarcity and Surfeit: The Ecology of Africa’s Conflicts (pp. 243–319). Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies. Therefore, access to water is one of the causes of conflict in South Omo.8Yohannes, Gebre Michael; Hadgu, Kassaye; and Ambaye, Zerihun (2005) ‘Addressing pastoralist conflict in Ethiopia: The case of the Kuraz and Hamer sub-districts of south Omo zone’, IGAD, Available at: <https://land.igad.int/index.php/documents-1/countries/ethiopia/conflict-1/33-addressing-pastoralist-conflict-in-ethiopia-the-case-of-the-kuraz-and-hamer-sub-districts-of-south-omo-zone/file> [Date accessed: 30 January, 2024]. The interview respondents and FGD discussants also confirm the continuity of the problem and the competition to use the existing natural water-points resulted in conflict among the community. The Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) cluster programme and various non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like Christian Aid constructed water schemes to reduce the shortage of water.9Humanitarian Response (2023) ‘Wash Cluster Ethiopia Update’, report, 14 February, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-wash-cluster-coordination-meeting-01-february-2023-meeting-minutes> [Date accessed: 30 January, 2024]. However, the shortage of water for humans and their livestock is still not resolved. People try to gain access to and control of water-points, which often results in conflict and violence.

The changing circumstances of conflict and conflict actors in the study area

The pastoral conflict dynamics in the Nyangatom, Dassanech, and Hammer community are not improving.10IGAD (2022) op. cit. As explained above, resource-based grievances in the study area are the main sources of violence. The parties in these conflicts are internal – in the Dassanech, Hammer and Nyangatom community – and external – cross-border actors, including elders, youths and the political actors from Ethiopia and Kenya concerned with protecting the interests of their communities. Conflict in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities can be regarded as disputes and struggles over inadequate resources of water and pasture, which could result in violence and destruction. The dominant pastoral livelihood and, to some level, the agro-pastoralist way of life are characterised by livestock keeping and crop production with sessional movement in search of pasture and water. The government institutions appear ineffective in the governance of the problem and they do not seem to have taken action to bring about sustainable change in resource-based conflict contexts.

There are also problems associated with drought and environmental degradation, which contribute to increased incidents of pastoral and agro-pastoral conflicts. The loss of cattle due to a lack of water and pasture severely affects the continued existence of the pastoralist and agro-pastoralists, as their livelihoods depend on this. The climatic conditions and resource degradation make the conflict in the study area protracted. As Galtung asserts, conflicts become dynamic and protracted if not adequately dealt with during the initial stages in which underlying conflict will manifest, as has been the case in the study area.11Galtung, Johan (1996) Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. London: SAGE. The pastoral groups become radicalised with hostile attitudes and aggressive behaviours against each other due to competition for resources. The other form of conflict among pastoralists includes cattle-raiding, which is linked to commercial and cultural practices among the communities. To end the protracted conflict, it is critical to change the perceptions of the pastoralists and agro-pastoralists through peacebuilding interventions like providing peace education.

Conflict prevention mechanisms in the study area

The study findings revealed the presence of various conflict prevention mechanisms in the study area, including peace dialogues among the community, awareness-raising on the importance of peaceful relations, and taking lawful action against conflict parties, including using conflict early-warning and response systems of the government. Governments can build collaboration between affected communities and strengthen their systems by using community members as channels of communication and sources of information, specifically cattle keepers.

Early-warning actions in the study area

The study indicated that the systems of information on impending conflict in the area and the awareness of conflict workers on the existing systems can be enabled to prevent conflicts in the area. This finding is in line with the assertion of the conflict prevention theory that an early-warning mechanism can be useful in identifying and forestalling impending conflicts and handling the drivers of conflict. Conflict information sharing at the grassroots level, awareness creation by various NGOs, the presence of frameworks for peace dialogues using traditional leaders, the coordination with government security systems, and the creation of water development plans are identified as early-warning mechanisms present in the area. Sharing information with concerned bodies and creating awareness are found to be the most significant conflict early-warning mechanisms in the area. Cattle keepers, peace committees, women, and government conflict workers play a central role in the implementation of early-warning mechanisms because they are within the community. The existing early-warning systems are weak and ineffective at facilitating a peaceful coexistence in the community as they do not build trust among the communities.

Conclusions

The conflict in Nyangatom, Hammer and Dassanech community of South Omo, Ethiopia, is complex and encompasses social, legal and economic issues. The violent conflict is seasonal, occurring in dry seasons as resource scarcity increases. Conflicts over pasture, water, animal raiding, fishing areas, and land claims are the major causes of violence. Conflict early-warning mechanisms, such as information sharing, peace dialogues, and negotiation have played a vital role in the forestalling and resolution of conflict in the study area. The findings affirm the early detection of the drivers of conflict and the application of preventive responses, such as peace dialogue and negotiations, are good practices in the study area. In addition, the weaknesses in the channels for the sharing of gathered early-warning information with the government on time undermine achievements to date in preventing destructive conflicts. The government and other bodies need to create conflict intervention mechanisms to reduce the negative impacts of conflict.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge Arba Minch University for its financial support in conducting this study.

Asmare Shetahun, Orcid ID: <https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4405-9236>