Climate change in Africa has led to a marked increase in security risks. The African Climate Security Risk Assessment (ACRA), a new African Union-led assessment, analyses the interlinkages between climate, peace and security across the African continent and identifies existing good practices. What emerges is a complex picture of growing threats, remaining challenges and entry points to better address these risks.

The adverse impacts of the climate crisis are strongly felt across the African continent. While being one of the smallest contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions, historically and per capita today, African states remain some of the most adversely affected. Climate impacts are already, and with increasing intensity, exacerbating existing grievances and putting livelihoods, food, water and energy security under pressure, particularly for the most marginalised groups.

Environmental conditions have always influenced how conflict materialises in different contexts. Yet the climate crisis is now leading to a myriad of climate shocks and slow on-set effects, including heatwaves, droughts, cyclones, flooding, and rainfall variability and unpredictability, which will permanently alter the state of livelihoods and resource availability on the African continent. These climate drivers interact with historical legacies such as colonial heritage, unsustainable resource-extraction, weak state capacity and the proliferation of armed groups. As a result, these factors increase the vulnerability of African states, leaving them in a disadvantaged position to cope, withstand and respond to climate security risks.

A growing need for proactive, anticipatory approaches to address the climate security nexus in Africa remains unfulfilled, leaving the continent in a reactive and responsive state.

Tweet

The African Climate Security Risk Assessment

This awareness, supported by a growing body of scholarship, has prompted the African Union (AU) to act. In the absence of a United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution, regional and member state actors, such as the AU, are filling the gap to drive forward the agenda and coordinate efforts on climate, peace and security. In 2021, the AU’s Peace and Security Council requested the AU Commission to conduct a climate security risk assessment to provide an overview of risks across the continent. This assessment, the African Climate Security Risk Assessment (ACRA), is nearing completion, with its executive summary launched at COP28.

The ACRA was conducted in close exchange with the AU’s Regional Economic Communities. During regional consultations, stakeholders came together to collect input on regional climate security risks. Supported throughout by adelphi and developed under the Weathering Risk methodology, the assessment provides an understanding of climate-related security risks through science-based, context-specific analysis. Based on the concept of ‘human security’, which is people-centred and includes economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security, the ACRA accounts for political contexts, histories of conflict, the political economy, as well as power and governance structures.

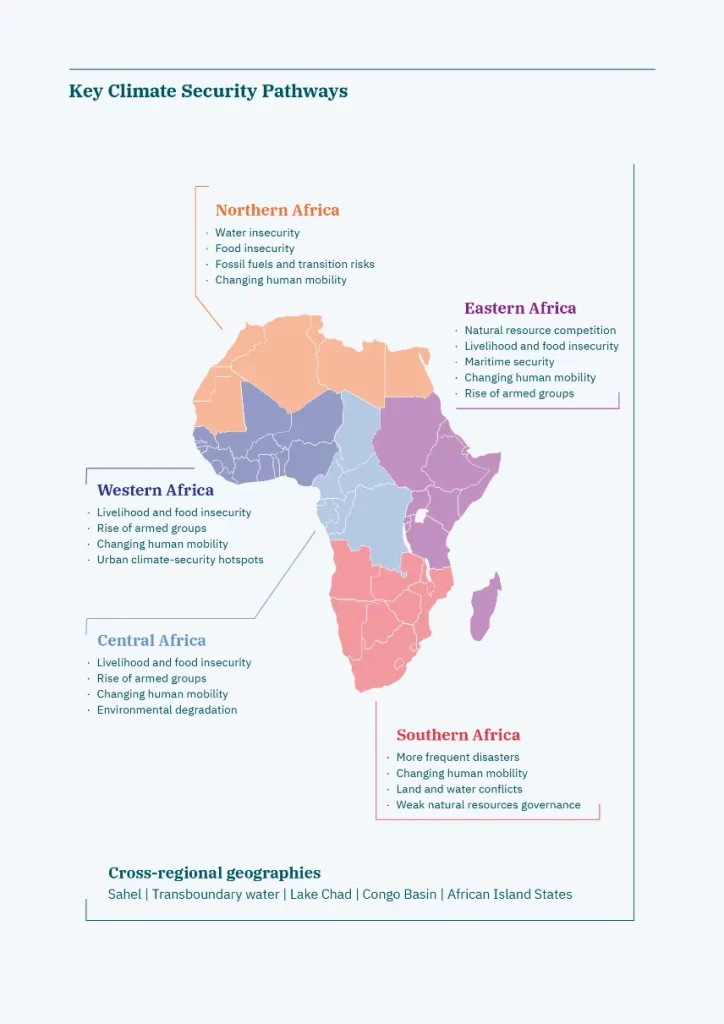

The ACRA identifies tailored entry points by emphasising and understanding the specific African sub-regional contexts in which climate-security risks play out. It focuses on understanding how local knowledge and traditions, social institutions, formal and informal governance and culture shape both vulnerability and resilience to climate-related security risks. It first compares regional climate-security pathways, responses and good practices in Northern Africa, Western Africa, Central Africa, East Africa and Southern Africa. In a second step, these regional findings are then used to address climate-related security risks across the continent.

Common risks and challenges

These climate security pathways, illustrated in the overview graphic above, account for specific contexts in each of the AU’s official regions. Additionally, the assessment provides space dedicated to specific geographies affected by climate change in unique ways, including the Sahel and African island states. Drawing insights from across Africa in a continent-wide report allows for identification of both differences and commonalities in climate security risks.

Action on many fronts is still lagging behind in relation to the level of risk associated with climate change. Three main areas are yet to be scaled up.

Firstly, strengthening African capacities and institutions for preventive action and resilience building should be prioritised. A growing need for proactive, anticipatory approaches to address the climate security nexus in Africa remains unfulfilled, leaving the continent in a reactive and responsive state. This could be addressed by mainstreaming climate, peace and security considerations in all relevant strategic and policy frameworks, including integrating climate and conflict early warning and early action (EWEA) systems on the continent.

Making peacebuilding and conflict prevention climate-responsive and making climate action conflict-sensitive should be another priority. Through an AU-led training facility for climate security, coordination between the regional and continental structures could be facilitated and championed. In this regard, stocktaking of indigenous knowledge (IK) and localised experiences on sustainable natural resource management and resilience, as well as the meaningful inclusion and participation of women and youth groups, could lead to positive, large-scale (co)benefits.

Secondly, while acknowledging the strides taken to invest in climate financing for peace mechanisms, access and availability of finance still falls dramatically short. There is an urgent need to invest more in risk prevention and resilience building, including better and easier access to adaptation finance and investments in absorption capacities.

Assuring that financing schemes reach the most vulnerable people living in conflict and fragility-affected contexts throughout Africa is key. In many instances, climate finance takes the form of loans or non-grant instruments, which create barriers to access for communities that bear little historical responsibility for climate change and are simultaneously grappling with multifaceted risks of prolonged violence and weak governance. Operationalising African-owned and managed facilities, such as the African Risk Facility, with sufficient financing, and aligning those with development priorities to lift populations out of poverty is pivotal in addressing climate-related security risks for and by Africans.

The third area needing urgent action is addressing structural and historical injustices and ensuring a just, equitable and peaceful green transition, which also encompasses a geopolitical dimension and requires international cooperation. Actors outside the African continent, including multinational firms, must fulfil their responsibility by finding sustainable and equitable models for extracting resources required for decarbonisation and by phasing out fossil fuel extraction in favour of investments in renewable energy. The ACRA demonstrates the security risks of failing to do so.

There is an urgent need to invest more in risk prevention and resilience building, including better and easier access to adaptation finance and investments in absorption capacities.

Tweet

The way forward

Following its upcoming launch, the ACRA can provide a common basis and foundation to discuss climate security on the African continent. With extensive discussion of Africa’s climate security risks and a diverse array of regional perspectives, the ACRA is a comprehensive account of risks and opportunities to respond to African climate security risks. The assessment has already informed the AU Commission Chairperson’s Report on the nexus. In the coming months after publication, these insights shall be the basis for discussions about adopting a Common African Position on climate, peace and security within the AU. Agreeing on such a Common Position would not only allow productive debate on how to further integrate responses across the continent – it would also send a strong political signal internationally to take climate security seriously and to enable its implementation through adequate and accessible financing.

Jakob Gomolka is an Analyst in Adelphi’s Climate Diplomacy and Security team. Yosr Khèdr is a Project Assistant in Adelphi’s Climate Diplomacy and Security team.