Introduction

The military has been an important institution for protecting States from external threats since antiquity. In fulfilling this fundamental role, military institutions have also posed security risks to their own governments, given that the ‘ability to use coercive force, though necessary to defend the nation against threats, creates the danger that the military will turn its weapons on the very regime that empowered its existence’.[1] Military personnel can fuel civil conflicts and undermine the stability of political regimes mostly in States with loose political control of the military. As Douglass North, John Wallis and Barry Weingast have argued, ‘Societies experiencing a civil war, by definition, do not have consolidated control of the military’.[2] In Africa, military institutions have, on one hand, helped to protect States from both internal and external threats, including local insurgencies. On the other hand, they have destabilised several political regimes through coup d’états. Military coups – ‘when the military, or a section of the military, turns its coercive power against the apex of the state, establishes itself there, and the rest of the state takes its orders from the new regime’[3] – have been relatively common in post-independent African States,[4] thereby raising several issues, including how to understand the relationship between politics and military coups. This article contributes to the discussion by highlighting how coups are a continuation of politics by other means, particularly in West Africa.

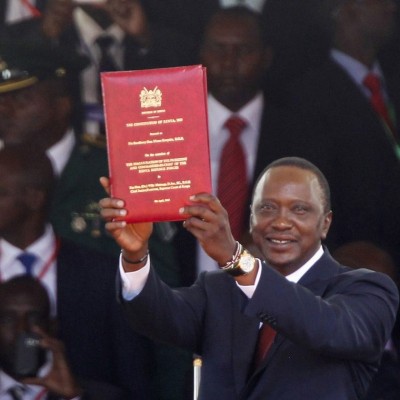

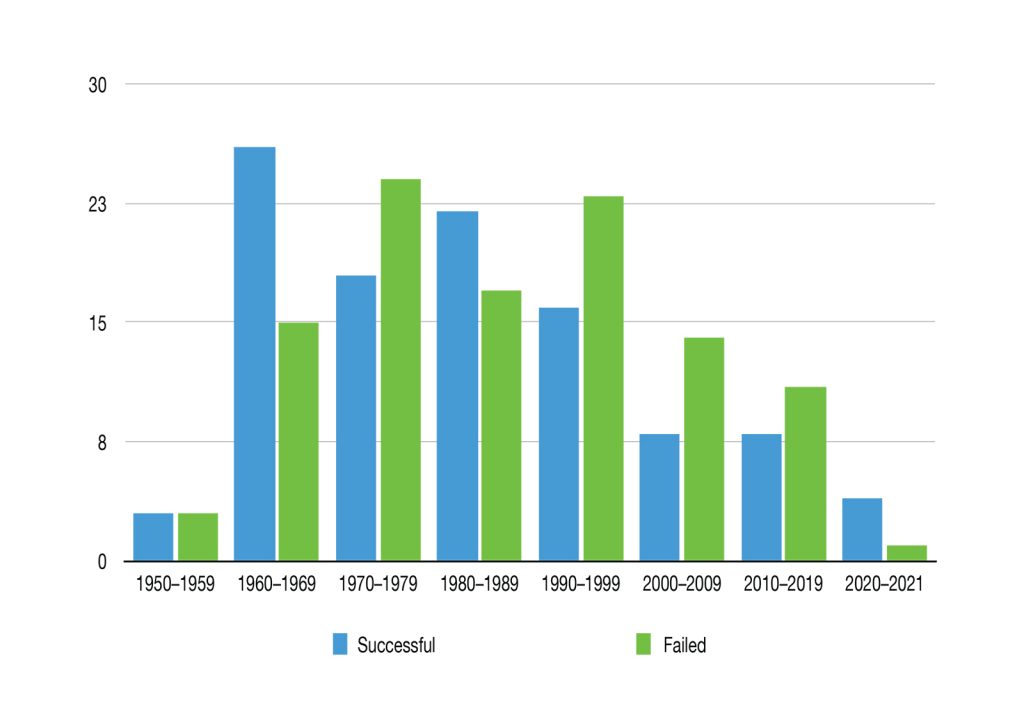

Figure 1: Military Coups in Africa, 1950-2021[5]

African States have experienced over 200 military takeovers between the 1960s and 2012.[6] Many analysts believed that coups were ‘going out of fashion in Africa’ by 2015 due to the limited cases on the continent.[7] At present, coups are widely seen to be ‘on the rise’[8] or ‘dangerously back in fashion’[9] in Africa, as some countries, such as Guinea Bissau, Guinea, Mali, Chad, Sudan, and Burkina Faso, have experienced a series of successful and failed military takeovers over the last three years. Apart from the foiled attempt to overthrow Guinea Bissau’s current president, Umaro Sissoco Embaló, on 1 February 2022, Burkina Faso’s most recent successful coup, in which President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was deposed by an army led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba on 24 January 2022, underscores how West African States are the most burdened by military coups on the continent. This has raised several concerns in the sub-region and questions the relevance of the regional organisation, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with respect to the maintenance of peace and security in West Africa.

Several reasons have been given for coups in Africa, including modernisation, cultural pluralism, soldiers’ greed and grievances, poor governance, corruption, autocracy, limited economic growth, and low-income levels, among other factors.[10] Many of the discussions on the causes of military coups in Africa have focused on internal actors and factors, and thus underestimated the pivotal role of foreign entities. While a few external factors, such as colonial heritage and the Cold War between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union, have been included in the causes of military coups in Africa,[11] such discussions have not been convincingly presented. For example, Robin Luckham et al. claim that disparate political systems inherited from Europeans have led to military coups in Africa.[12] This claim was debunked several decades ago by Alan Wells and William Tardoff.[13] Also, political and socioeconomic factors, such as corruption and poor governance in Africa, are sometimes discussed as though they do not exist in other parts of the world. To address these and other limitations in the literature, the article advances a twofold argument. First, it argues that military coups in Africa are best understood through the lens of neocolonialism. Second, the analysis highlights how military overthrows, even though they are not desirable in most States, are a continuation of politics by other means. The article begins by establishing the link between neocolonialism and military coups in Africa before discussing how military coups in Africa are politics by other means.

Neocolonialism and Military Coups in Africa

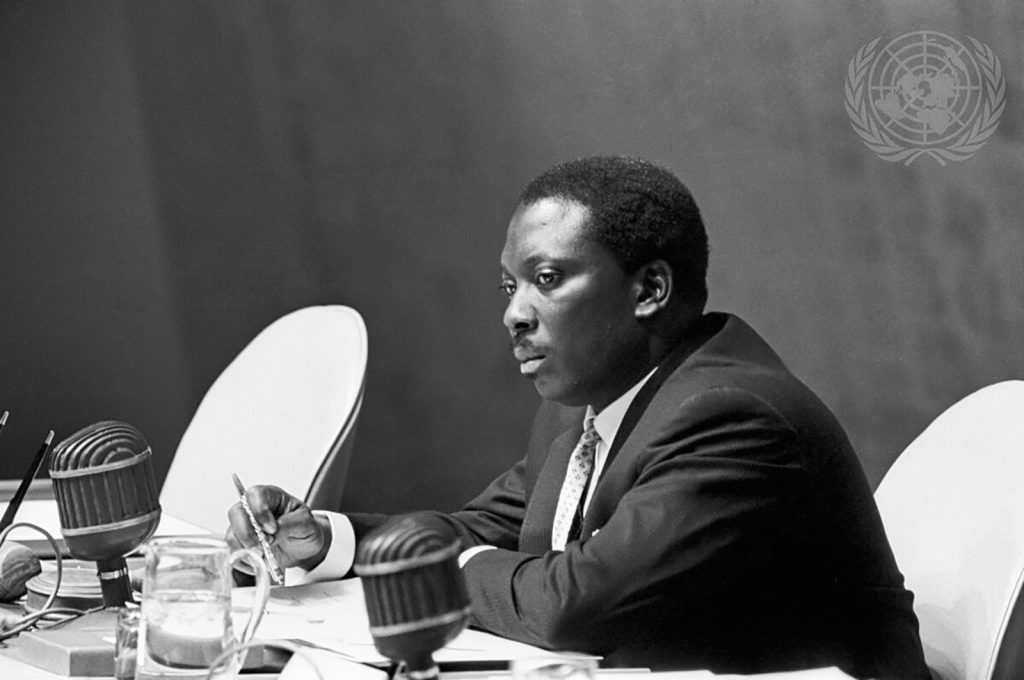

The idea of neocolonialism emerged when the first generation of political leaders in modern African States, including Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Nigeria’s Nnamdi Azikiwe, were confronted with post-independence contradictions. Specifically, these African leaders realised that they had political but not economic control of their States, despite achieving independence from the colonisers. Alex Quaison-Sackey, Ghana’s former Foreign Minister who is credited with internationalising the term ‘neocolonialism’ at a United Nations (UN) General Assembly meeting in 1958, defines neocolonialism as ‘the practice of granting a sort of independence with the concealed intention of making the liberated country a client-state, and controlling it effectively by means other than political ones’[14]. Put differently, neocolonialism underlines both the transfer of political power from the European colonisers to African leaders and the persistence of foreign control of African economies through other means. Or, as Kwame Nkrumah has argued: ‘The essence of neocolonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside’.[15]

Neocolonialism is also visible in how former colonisers, including France and Britain, have undermined Africa’s political stability through coups. For example, it is now common knowledge that the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was assisted by Britain to finance, mastermind, and tele-guide the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah in 1966 because they considered him the greatest threat to their interests.[16] Furthermore, the former colonisers are alleged to be linked to several political assassinations in Africa. For example, France has been accused of being linked to the killing of at least 22 African presidents since 1963, including Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara.[17]

Despite the idea of neocolonialism helping to understand several political and socioeconomic issues, including coups in modern Africa, several attempts have been made to discredit the term since its inception. For example, Alex Douglas-Home, a former British Foreign Secretary, claimed in 1964 that there is ‘no place in Britain’s political dictionary’ for the term neocolonialism as it is not real.[18] Neocolonialism has also been associated with outdated vulgar forms of Marxism and dependency theory, as well as uncompromising African leaders, such as Kwame Nkrumah and Robert Mugabe, who have been labelled ‘tyrants’.[19] Currently, neocolonialism is widely used in African, British, and other political discourses as it is relevant for understanding modern Africa and some other societies.[20]

Given the longstanding link between foreign powers and insecurities in Africa, one cannot ignore the involvement of both local and foreign actors in the current wave of military coups in Africa. In September 2021, for example, news broke of how Mali’s current military regime initiated a move to hire Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group, which has been accused of serious human rights abuses in Africa. The critical question that arose from this news was whether the Russian mercenaries and/or any other foreign groups were involved in the coup that toppled Mali’s President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in 2020.

To summarise, the idea of neocolonialism helps to understand how both foreign and local actors come together to fuel military coups in Africa, among other insights. Most sub-Saharan African States can still be classified as neocolonial since they continue to depend heavily on external support, including military and economic aid, for their survival. Against this backdrop, foreign powers find it relatively easy to fuel political and socioeconomic problems, including coups in sub-Saharan Africa, whenever this will help advance their interests. Having discussed military coups in Africa through the lens of neocolonialism, the next section analyses the link between coups and politics in neocolonial Africa.

Military Coups and African Politics

One distinctive feature of military institutions, as pointed out in the introduction, is their access to weapons and coercive force, generally for the State’s protection. It follows that military institutions’ significance usually comes to light during inter-state wars – ‘organized violence carried on by political units against each other’[21] and local combats – organised violence between governments and rebels. War is, therefore, ‘the military dimension of society’, since State armies are born out of and require cooperation from society to fight wars.[22] In turn, war has been understood as part of politics ever since von Clausewitz famously argued: ‘War is a continuation of political intercourse with a mixture of other means’.[23] Indeed, the declaration and strategies of war require deep thinking and effective policies for States to engage in combat. Similarly, military coups are a continuation of politics by other means because coup plotters need to think critically about why, when, and how to topple political regimes.

In this vein, Burkina Faso’s Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba cited the failure of the country’s ousted President Roch Kaboré to contain violence by Islamic militants as a key reason why the military had to stage the most recent coup in this West African State, which occurred in January 2022.[24] Damiba and his military colleagues were smart enough to identify a major weakness in Kaboré’s regime, which is the rising insecurities in Burkina Faso, as a justification for the coup. Also, deep insecurities, weak political leadership, and corruption have been highlighted as key factors that led to Colonel Assimi Goïta’s overthrow of Malian President Bah Ndaw and Prime Minister Moctar Ouane in 2020.[25] It follows that the degree of success and failure in coup plots is heavily dependent on the depth of knowledge and quality of tactical mobilisation by the military. Any display of incessant power abuse, careless leadership, ill-thought-out political decisions, perceived and actual widespread corruption, and regime weakness, among other factors which distance political leadership from the plight of citizens, increases the chances of military coup occurrence. This is evident in West Africa, where the political system ‘works for the political class, that are well paid, that enjoy a lot from State resources, and who display arrogance and complete lack of concern about the welfare of citizens’, thereby creating conducive conditions for military coups.[26]

Therefore, in place of the conventional way of understanding military coups as interrupting politics in Africa and elsewhere, military takeovers need to be understood as politics using arms to change governments forcefully. In general, the discussion of military diplomacy has focused on how armies, including those in the US, help to spread democracy and engage in humanitarian interventions, among other diplomatic duties.[27] However, military diplomacy, particularly in West Africa, is also characterised by military coups. The latter is part of diplomacy that relies on arms or force – rather than electoral campaigns and voting – to transition from one political regime to another. As opposed to political parties that mostly lose and win elections based on their past achievements and campaign strategies, the failures and successes of military coups are largely dependent on the armed strategies that the military adopts and the weakness of the State. The effectiveness of military tactics, including the timing of coups, public grievances at stake, and help from foreign allies, contributes significantly to successful coups in neocolonial Africa. While the tenure of military regimes that assume political power through coups may be short-lived and not under constitutional rule, they take full control of States during their time in office, just as democratically elected governments do.

Jibrin Ibrahim has highlighted how ECOWAS’ failure to respond to ‘constitutional coups’, that is, the elongation of presidential tenures by incumbent presidents, and massive electoral fraud has fuelled coups in West Africa.[28] Indeed, political leaders such as Mamadou Tandja of Niger, Abdoulaye Wade of Senegal, and Alpha Condé of Guinea were all forced out of their presidential office by the military, after altering their countries’ constitutions to serve more than two terms in office. ECOWAS is infamous for mainly responding to military coups with threats, including setting deadlines for elections and sanctions, such as shutting down the borders of coup-affected States.

In summary, military coups are a continuation of politics by other means, especially in West Africa where the political systems favour only the political class to the detriment of the masses. Unlike democratic governments with political mandates based on constitutions and election outcomes, among other things, the political mandate of military coup leaders stems from the barrel of the gun.

Conclusion

The article highlighted how military coups in Africa are best understood through the lens of neocolonialism. Neocolonialism helps to explain how modern African States have remained economically and militarily too weak to avert local and foreign threats since independence.[29] The heavy involvement of foreign powers in military coups and political assassinations in Africa, as well as the adoption of neocolonial currencies, such as the CFA franc by former French colonies in Africa, underlines the persistence of neocolonialism. Against this backdrop, Walter Rodney has argued: ‘The phenomenon of neo-colonialism cries out for extensive investigation in order to formulate the strategy and tactics of African emancipation and development’.[30] The resurgence of military coups in West Africa needs to be investigated further through the lens of neocolonialism.

Furthermore, the article discussed why military coups are a continuation of politics by other means. This is particularly evident in West Africa, where military takeovers are relatively common in democratic systems that favour only the political class. The current understanding of a political organisation in Africa has largely been restricted to bureaucratic institutions in which political leadership emerges from elections. However, political leadership is also achieved through military coups. Access to weapons and legitimate force on behalf of the State can allow military personnel to remove and replace Heads of States from office. Coups, therefore, are a continuation of politics by other means, even though they are generally not desirable in most States. Governments mostly create conducive conditions for military coups whenever they violate existing formal institutional arrangements, including constitutions and other legal systems that support political leadership. This is mainly seen in West Africa, where questionable political decisions, including elongating presidential terms in office and failing to provide adequate security to the local population, have fuelled military coups.

The policy implication is that governments must diligently honour social contracts with the people, which should serve as the foundation for their position in States. The political class must guard against irresponsible actions, including widespread theft of public resources and constitutional coups, as these create grounds conducive to military coups. West African politicians, in particular, need to transform their understanding of political leadership and how to relate to the local population in a more relevant way to limit coups in the region.

Dr E. Nana Amoateng is a Research Fellow at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy at the University of Ghana.

Endnotes

[1] Feaver, Peter D. (1999). ‘Civil-Military Relations’, Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 211–241.

[2] North, Douglass. C.; Wallis, John. J.; and Weingast, Barry. R. (2009) Violence and Social Orders,New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 153.

[3] Sampford, Charles (1991) ‘Coups d’ÉEtat and Law’, in de Attwooll, Elspeth (ed.), Shaping Revolution, Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, p. 164.

[4] Barka, Habiba Ben and Ncube, Mthuli (2012) ‘Political Fragility in Africa: Are Military Coups d’État a Never-Ending Phenomenon?’ African Development Bank, Available at: <https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/economic_brief_-_political_fragility_in_africa_are_military_coups_detat_a_never_ending_phenomenon.pdf> [Accessed January 2022].

[5] Nile Post (2021) ‘Are Military Coups on the Rise Again in Africa?’ 7 September, Available at: <http://nilepost.co.ug/2021/09/07/are-military-coups-on-the-rise-again-in-africa> [Accessed January 2022].

[6] Barka, Habiba Ben and Ncube, Mthuli (2012) op. cit., p. 1.

[7] Ntomba, Reginald (2015) ‘Why are Military Coups Going Out of Fashion in Africa?’ New African, 11 November, Available at: <https://newafricanmagazine.com/11522/> [Accessed January 2022].

[8] Mwai, Peter (2021) ‘Sudan Coup: Are Military Takeovers on the Rise in Africa?’ BBC News, 26 October, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-46783600> [Accessed January 2022].

[9] Seigler, Sean M. (2021) ‘Are Military Coups Back in Style in Africa?’ RAND, 1 December, Available at: <https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/12/are-military-coups-back-in-style-in-africa.html> [Accessed January 2022].

[10] Barka, Habiba Ben and Ncube, Mthuli (2012) op. cit.; McBride, Michael (2004) ‘Crises, Coups, and Entry-deterring Reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Paper presented at the Public Choice Society Seminar, University of California, June; Johnson, Thomas H.; Slater, Robert O.; and McGowan, Pat (1984) ‘Explaining African Military Coups d’État, 1960-1982’, American Political Science Review, 78(3), 622–640.

[11] Barka, Habiba Ben and Ncube, Mthuli (2012) op. cit.

[12] Luckham, Robin; Ismail, Ahmed; Muggah, Robert; and White, Sarah (2001) ‘Conflict and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Assessment of the Issues and Evidence’, IDS Working Paper No. 128, Brighton, Sussex: Institute of Development Issues.

[13] Wells, Alan (1974) ‘The Coup in Theory and Practice: Independent Black Africa in the 1960s’, American Journal of Sociology, 79(4), 871–887; Tardoff, William (1993) Government and Politics in Africa, 2nd edn, London: Macmillan.

[14] Uzoigwe, Godfrey N. (2019) ‘Neocolonialism is Dead: Long Live Neocolonialism’, Journal of Global South Studies, 36(1), 59–87.

[15] Nkrumah, Kwame (1965) Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism,London: PANAF, p. ix.

[16] Quist-Adade, Charles (2016) ‘The Coup that Set Ghana and Africa 50 Years Back’, Pambazuka News, 2 March, Available at: <https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/coup-set-ghana-and-africa-50-years-back> [Accessed January 2022]; Doh, Emmanuel F. (2008) Africa’s Political Wastelands: The Bastardization of Cameroon,Bamenda: Langaa Research & Publishing Common Initiative Group.

[17] Chiwanza, Takudzwa (2019) ‘France has Assassinated 22 African Presidents Since 1963’, The African Exponent, 29 June 2019, Available at: <https://www.africanexponent.com/post/10487-france-has-always-carried-evil-imperialism-with-it> [Accessed January 2022].

[18] Uzoigwe, Godfrey (2019) op. cit., p. 63.

[19] Langan, Mark (2018) Neo-colonialism and the Poverty of ‘Development’ in Africa,London: Palgrave MacMillan.

[20] Uzoigwe, Godfrey (2019) op. cit.

[21] Bull, Hedley (1977) The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics,London: Macmillan, p. 184.

[22] Foucault, Michel (1996) ‘What Our Present Is’, in Lotringer, Sylvère (ed.), Foucault Live: Collected Interviews 1961-198,New York: Semiotext(e).

[23] Baylis, John; Smith, Steve; and Owens, Patricia (eds) (2014) The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, 6th edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 217.

[24] BBC News (2022) ‘Burkina Faso Coup Leader Damiba Gives First Speech’, 28 January, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-60164531> [Accessed February 2022].

[25] Melly, Paul (2021) ‘Mali’s Coup: How to Solve the Conundrum’, BBC News, 27 May, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57255601> [Accessed February 2022].

[26] Ibrahim, Jibrin (2022) ‘The Return of the Military in West Africa?’ Council on Foreign Relations – Ghana Virtual Conference Series, 3 February, Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6IcDFlilopk&ab_channel=CouncilonForeignRelations%2CGhana> [Accessed February 2022].

[27] See Ebitz, Amy (2019) ‘The Use of Military Diplomacy in Great Power Competition’, Brookings, 12 February, Available at: <https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/02/12/the-use-of-military-diplomacy-in-great-power-competition> [Accessed February 2022].

[28] Ibrahim, Jibrin (2022) op. cit.

[29] Langan, Mark (2018) op. cit.; Nkrumah, Kwame (1965) op. cit.

[30] Rodney, Walter (2018) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,London: Verso, p. xiii.