Any peace in Darfur must be built on solutions that go to the root causes of the conflict [1]

Ban Ki-moon (former United Nations Secretary-General)

Background to the Conflict in Darfur

The relationship between climate change and deadly conflict is complex and context-specific, but it is undeniable that climate change is a threat multiplier that is already increasing food insecurity, water scarcity and resource competition, while disrupting livelihoods and spurring migration. In turn, deadly conflict and political instability are contributing to climate change.[2]

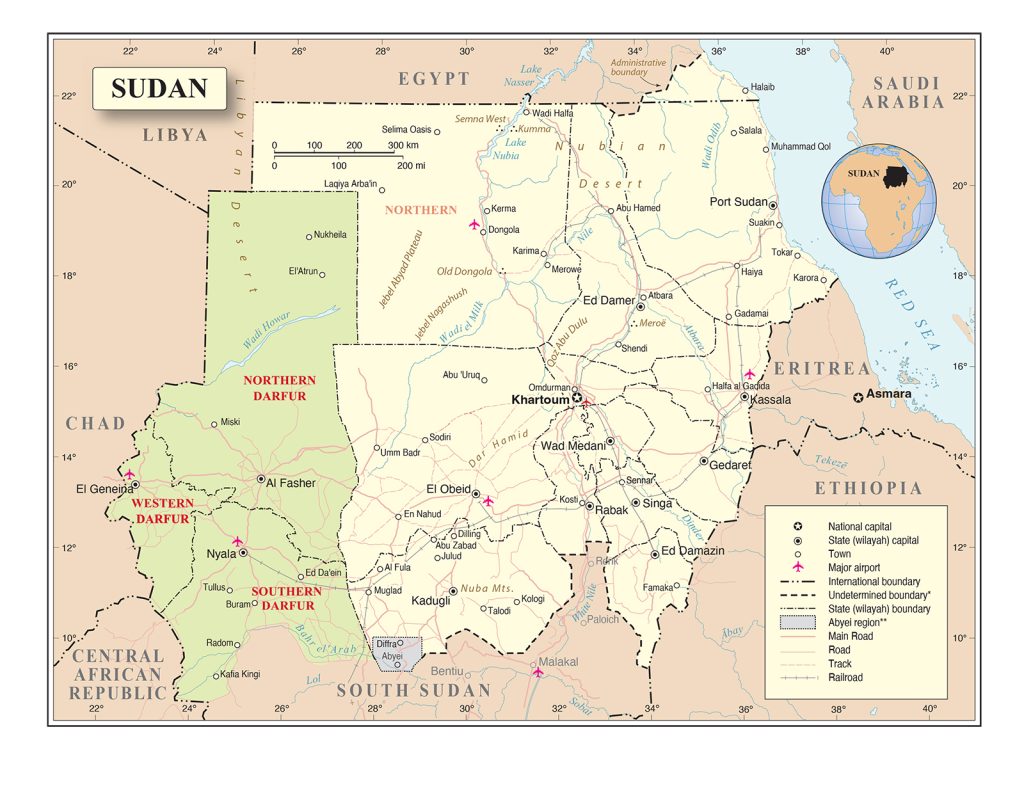

Darfur captured international headlines in 2004 when United States (US) Secretary of State Colin Powell declared that genocide was occurring in Sudan in his testimony to the US Senate.[3] The early-2000s conflict in Darfur between rebel groups on one side and government forces and allied militias on the other caused an estimated 300 000 deaths, and about 2.5 million people live in displacement camps across Darfur.[4] Most observers agree that the immediate cause was a regional rebellion, to which Khartoum responded by recruiting Arab militias, known as the Janjaweed, to wage a campaign of ethnic cleansing against African civilians.[5] They also argue that the three core drivers of violence in Darfur at present are disputes over land and resources, the complex network of militias and paramilitary forces, and the weakness of the rule of law and security institutions.[6]

Eighteen years after the eruption of the conflict in Darfur, these conclusions regarding the main causes and triggers of the conflict remain valid. In 2021, despite the signed Juba Peace Agreement, the security situation in Darfur remained volatile, with significant inter-communal violence and fighting between government forces and rebels in the Jebel Marra area. The instability in the region continues to cause large-scale displacement, with more than 200 000 people displaced in Darfur since the beginning of 2021.[7]

The Root Causes of the Conflict

When analysing the root causes of the conflict in Darfur and building strategies for addressing displacement, international and regional actors often forget that the origins of the conflict are multiple and complicated, ethnoreligious and environmental. Since the beginning of armed violence in Darfur, the region has been labelled the “first climate change conflict” by many observers, given the convergence of environmental and political factors leading to the conflict. Sudan, in general, and the Darfur region, in particular, are home to diverse ecological zones, ranging from arid deserts in the north to semi-tropical environments in the south. In the decades leading up to the 2003 outbreak of the conflict in Darfur, the Sahel region of northern Sudan witnessed the Sahara Desert advance southward by almost a mile each year, with a decrease in annual median rainfall of 15% to 30%.[8] These factors led then United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to comment in 2007:

Almost invariably, we discuss Darfur in a convenient military and political shorthand — an ethnic conflict pitting Arab militias against black rebels and farmers. Look to its roots, though, and you discover a more complex dynamic. Amid the diverse social and political causes, the Darfur conflict began as an ecological crisis, arising at least in part from climate change.[9]

An 18-month study of Sudan by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in 2007 also concluded that the conflict in Darfur has been driven by climate change and environmental degradation, which threaten to trigger a succession of new wars across Africa, unless more is done to contain the damage. The UNEP reported, “Environmental degradation, as well as regional climate instability and change, are major underlying causes of food insecurity and conflict in Darfur – and potential catalysts for future conflict throughout central and eastern Sudan and other countries in the Sahel belt”[10]. Although these factors are well known to those working in this field in Darfur, it is not commonly understood outside the region. Yet it has major implications for the prospects of peace, recovery, and rural development in Darfur and the Sahel.

Climate Change and the Human Impact on the Environment in Darfur

Environmental degradation has intensified in recent years, undermining Darfur’s future prospects. This degradation is chiefly driven by two forces: climate change and human impact on the environment. Climate change is most visible in erratic rain levels and associated increases in drought. Partially as a result of these changes, many farmers cultivate their fields more intensively, and many have expanded to the detriment of surrounding forests and grazing land. Pastoralists, squeezed by the loss of rangelands, often over-graze their herds in smaller areas, further fuelling degradation.

The human impact on the environment is most visible in the area of deforestation, which constitutes a substantial threat, as Darfuris have cleared forests as an alternative or supplementary livelihoods strategy. Before the war broke out, tree cover in Darfur was already declining, with forests contracting at an average annual rate of over 1% between 1973 and 2006. Overall, Sudan has lost more forest cover than any other African country, and Darfur is clearly a major contributor to this trend. In fact, some forests around cities such as Nyala and El Geneina have disappeared entirely.[11]

Pressure on the environment is further intensified by current water consumption, better management of which will be crucial to Darfur’s future, including for related issues such as improved access to sanitation and health. If not addressed, all these factors will continue to lead to inter-communal conflicts and conflicts between farmers and pastoralists,[12] which often result in a significant loss of lives and mass displacement of the local population.

Current Patterns of Inter-communal Conflict and Displacement

The cycle of deadly violence in Darfur is ongoing. For example, on 16 January 2021, attacks on the Krinding camps in El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur State, led to the deaths of more than 160 people (most of them ethnic Massalit). The details of the attacks are horrific. The Arab tribal militia reportedly looted and burnt many houses and shops in the Krinding camps and surrounding areas. According to a statement to Sudan Television by the West Darfur Governor on 17 January 2021, almost a third of the camps were reduced to ashes. The flash update by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) on 14 February 2021 indicated that 180 000 people were displaced in El Geneina and the surrounding villages after the Krindig attack.[13] The attack followed the killing of an Arab man by a Massalit man during a quarrel on 15 January 2021. El Geneina city witnessed a similar revenge attack by some Arab militia at the end of December 2019.

The 2021 attack was a terrible reminder that security remains elusive in Darfur and impunity is still widespread in the long-troubled region. It also serves as a reminder that even small interpersonal disputes between members of different communities can quickly turn into large-scale violence and massive displacement of people who have already been displaced in the past.

The international community should, therefore, support the efforts of the Government of Sudan towards addressing the root causes of the violence in Sudan. The focus should be on early warning and early response to address imminent intercommunal conflicts in the region in a timely manner and avert the spread of violence. When analysing the root causes of intercommunal violence, it is important to pay sufficient attention to the environmental challenges and climate change as they often come up as the main reasons for such conflicts.

Successful Initiatives and Lessons Learnt from Previous Interventions

International, regional and national actors have long been trying to address the climate crisis in Darfur to reduce its impact on the civilian population. There have been both successful initiatives that need to be built upon and efforts that could not be sustained. Urbanisation, population growth, and the effects of climate change have increased pressure on Darfur’s forests. But the conflict has intensified the toll on Darfur’s trees at the precise moment when thousands of families need new sources of income.

In Darfur, the task of firewood collection falls to women. Reports of violent assaults on women collecting firewood have prompted the UN-African Union (AU) Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) to devise innovative solutions for protecting both women and the environment in Darfur. From May to October 2017, the Mission developed and implemented a project aimed at providing training to 800 rural and internally displaced persons (IDP) women on the production of fuel-efficient stoves in one of the most conflict-sensitive areas in Darfur: Sortony, North Darfur.

These stoves were specifically designed to reduce fuel consumption and provide a substitute for the traditional three-stone fire. They can be made of mud, clay or metal, and they use different types of fuels, such as fuelwood, charcoal, briquettes, biofuels, liquefied petroleum gas, or kerosene. In addition, they reduce the exposure of women and girls to conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), since they have to collect fuelwood less often. As fuel-efficient stoves can be made fairly easily from local materials and they consume less wood, their popularity is increasing.

The impact of the fuel-efficient stove project cannot be underestimated. According to the Sudanese National Forests Corporation, the amount of firewood saved by using fuel-efficient stoves in comparison to traditional open-fire cooking is over 50%.[14] Project beneficiaries were trained to produce fuel-efficient stoves using easily accessible, low-cost local materials, and they generate additional income by making and selling the stoves. A single household saves an average of 99 Sudanese pounds per day on firewood by using one of the new stoves. Women and girls are somewhat better protected from SGBV by this new initiative. Women and children’s health is also better protected from the smoke emissions of traditional stoves. Using the fuel-efficient stoves, cooking fires are more contained, which reduces the safety risks. Vegetation cover is also improved due to tree planting and reduced firewood extraction.

Fuel-efficient stoves have proved to play an important role in saving forests and improving women’s safety and security in humanitarian crises and post-conflict situations. However, such initiatives cannot be sustainable in the long term if they are not coupled with nationally owned environmental protection strategies and the effective rule of law.[15]

As far as unsustainable practices are concerned, the management of water resources has been sidelined since 2003, when there was a major humanitarian response to the Darfur conflict, by the need to concentrate on the provision of water for the large number of people displaced by the conflict. Emergency use of water resources in Darfur following short-term unsustainable approaches eventually replaced more comprehensive water resources planning and development. In some instances, this has caused alarming drops in the water table. Furthermore, the ready access to water in IDP camps has led to maladaptive livelihoods among the displaced, such as brickmaking, which has flourished in some camps through the use of water intended for drinking. Internalising such valid concerns as equity and social justice in resource utilisation calls for a strategic and integrated approach to water resources management.

Major Priorities for International, Regional and National Actors

Severe environmental degradation poses a direct threat to Darfur’s immediate stability and undermines future prospects for peace and prosperity. This degradation is the result of climate change, over which Darfuris have little control, as well as the impact of human activities. As discussed previously, environmental issues have frequently been at the root of the conflict in Darfur, as growing numbers of people compete for dwindling resources. Strengthening environmental management is, therefore, critical not only for resolving the current crisis, but also for promoting lasting solutions for Darfur in the longer term.

Therefore, one of the main priorities is to promote the use of alternative energy and technology, particularly for construction. Most Darfuris rely on firewood or charcoal to meet their energy needs, leading to untenable rates of deforestation. International, regional and national actors should promote alternative technologies that can attenuate the impact on natural resources. For example, for construction in Darfur, stabilised soil blocks (SSBs) have tremendous potential as an alternative to traditional bricks, which consume large quantities of firewood and water in the fabrication process. Stakeholders should support the use of SSB technology across Darfur, disseminating the necessary tools and inputs as widely as possible, and assisting traditional brick-makers in transitioning to new technology, including with necessary training.

The second priority is to improve water harvesting, access and management. International, regional and national actors should work with local counterparts to improve the management of water resources and expand access to water in a way that will promote sustainability. To achieve this objective, they should support integrated water resource management among local authorities and communities across Darfur.

Since deforestation poses an enormous threat to Darfur, and maladaptive livelihood strategies have dramatically accelerated the toll of the conflict on Darfur’s trees, the third priority is to support better management of forest resources. International, regional and international actors need to support participatory reforestation and afforestation efforts to promote better management. Such support could include the development of commercial woodlands and nurseries, as well as greater support for forest-based livelihoods derived from products such as gum arabic, honey, and hibiscus, among others.

All efforts should be complemented by intensive outreach to raise awareness. International, regional and national actors should dramatically increase community outreach on environmental issues to empower Darfuris to lead sustainable environmental management efforts. Outreach campaigns should explain the causes of environmental degradation and provide information on how specific adaptations could potentially reverse this decline.

Finally, international and regional actors should support the capacity of official institutions to conduct rigorous analysis and develop research-based environmental policies.

It should also be noted that, ultimately, all progress is the responsibility of local communities, their leaders, and the Government of Sudan. International and regional actors can support the fulfilment of these responsibilities by leveraging resources and expertise.

Zurab Elzarov is Chief of the Learning, Leadership and Management Development Section at the UN Department of Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance (DMSPC) at UN Headquarters in New York, and former Chief of the Civil Affairs and Protection of Civilians Sections at UNAMID.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of UNAMID or the UN.

Endnotes

[1] Ki-moon, Ban (2007) ‘A Climate Culprit in Darfur’, UN Secretary-General, 27 June, Available at: <https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/articles/2007-06-16/climate-culprit-darfur> [Accessed 7 January 2022].

[2] International Crisis Group (2008) ‘Climate Change and Conflict’, Available at: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/future-conflict/climate> [Accessed 10 January 2022].

[3] Weisman, Steven R. (2004) ‘Powell Declares Genocide in Sudan in Bid to Raise Pressure’, New York Times, 9 September, Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/09/international/africa/powell-declares-genocide-in-sudan-in-bid-to-raise.html> [Accessed 10 January 2022].

[4] Eltahir, Nafisa (2022) ‘More than 15,000 People Displaced in New Darfur Violence, UN Says’, Reuters, 27 January, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/more-than-15000-people-displaced-new-darfur-violence-un-says-2022-01-27> [Accessed 14 January 2022].

[5] Borger, Julia (2007) ‘Darfur Conflict Heralds Era of Wars Triggered by Climate Change, UN Report Warns’, The Guardian, 23 June, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2007/jun/23/sudan.climatechange> [Accessed 18 January 2022].

[6] International Peace Institute (2017) ‘Applying the HIPPO Recommendations to Darfur: Toward Strategic, Prioritized, and Sequenced Mandates’, June, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/1706_Applying-HIPPO-to-Darfur.pdf> [Accessed 22 January 2022].

[7] OCHA (2021) ‘Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot – July 2021’, 8 August, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Sudan_Humanitarian_Snapshot_Jul_2021_EN.pdf> [Accessed 25 January 2022].

[8] Sova, Chase (2017) ‘The First Climate Change Conflict’, World Food Program USA, 30 November, Available at: <https://www.wfpusa.org/articles/the-first-climate-change-conflict> [Accessed 28 January 2022].

[9] Ki-moon, Ban (2007) op. cit.

[10] UNEP (2007) Sudan Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment, Nairobi: UNEP, Available at: <https://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/UNEP_Sudan.pdf> [Accessed 1 February 2022].

[11] UN Sudan Office of the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator (2010) ‘Beyond Emergency Relief: Longer-term Trends and Priorities for UN Agencies in Darfur’, September, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/6AAEE62B2DC5EE8D852577AE0071F8E7-Full_Report.pdf> [Accessed 2 February 2022].

[12] Elzarov, Zurab (2021) ‘People on the Move: Addressing Vulnerabilities of Nomadic Communities in Darfur’, International Journal of Social Science and Economics, 1(2), 16–24, Available at: <http://www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/ijsse/article/view/4198/4664> [Accessed 4 February 2022].

[13] Amnesty International (2021) ‘Sudan: Horrific Attacks on Displacement Camps Show UN Peacekeepers Still Needed in Darfur’, March, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2021/03/sudan-horrific-attacks-on-displacement-camps-show-in-darfur> [Accessed 7 February 2022].

[14] Rijal, Emadeldin (2012) ‘Fuel-Efficient Stoves Protect Women, Environment’, Voices of Dafur, November, 3(8), 19–21, Available at: <https://issuu.com/vodarfur/docs/vod_november_2012_en> [Accessed 10 February 2022].

[15] Elzarov, Zurab (2018) ‘Protecting the Environment and Women in Darfur Through Fuel-Efficient Stoves’, Conflict Trends, 4, 30–37, Available at: <https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/protecting-the-environment-and-women-in-darfur-through-fuel-efficient-stoves> [Accessed 13 February 2022].