Over the past 24 months, global attention has been on the COVID-19 health pandemic, and, more recently on the unfolding war in the Ukraine. In parallel, Africa has experienced six military coups and two attempted coups. These events represent a sharp rise in such contested political transitions over the previous 10-year period and indicates the possibility of further instability on the continent.

Political transitions through peaceful democratic processes have been steadily ascendant in Africa. This is an achievement to be celebrated, particularly as the African Union reaches its 20th anniversary @jmartyns

Tweet

Political transitions through peaceful democratic processes have been steadily ascendant in Africa. This is an achievement to be celebrated, particularly as the African Union (AU) reaches its 20th anniversary. In the past two years alone, 19 countries in Africa held elections. In these elections, 37 percent were won by the opposition while approximately 63 percent were characterised by the re-election of the incumbency. This trend is consistent with the outcome of elections over the last decade (2011 to 2021), in which one out of three have been won by opposition parties.

African citizens have increasingly come to rely on elections as a foundation for demanding change, accountability, and responsiveness from their governments. Still, the recent rise in military coups, if not addressed, may undermine progress made over the last three decades in the promotion of constitutional order.

The AU denounced the uptick in military coups at its January 2022 Summit, and in April issued a declaration calling for renewed efforts to tackle the resurgence in what it terms ‘unconstitutional changes of government’ (encompassing coups and other forms of disruption to constitutional order). UN Secretary General António Guterres has urged the Security Council to act in response to an ‘epidemic of coups d’états’ unfolding on the world stage.

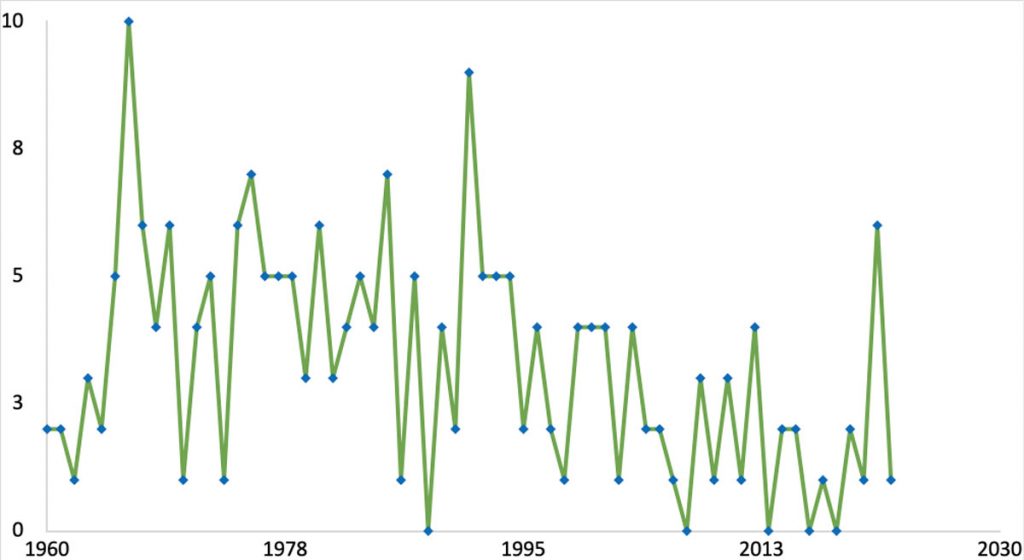

The rate of recent coups is equivalent to the total number of coups in the last decade, from 2010 to 2019. It also presents a striking parallel to the number of coups that Africa witnessed during the dominance of authoritarian regimes from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Pattern of Military coups in Africa (1960 to 2022)

The aftermath of coups d’états in Burkina Faso, Guinea-Conakry, Mali (twice) and Sudan, as well as a failed coup in Guinea-Bissau are still unfolding. The time is ripe to reflect: what explains this spike, and what can be done to prevent them and restore constitutional order when they occur?

Incompleteness of previous transitions, underlying development and governance shortfalls and related citizen frustration emerge as salient factors shaping the trajectory of the countries that experience coups @jmartyns

Tweet

The first issue to note, in looking into drivers, is the way in which earlier political transitions in some of the affected countries have been characterised by incompleteness. Since 2012, Mali has vacillated between transient civilian rule and military coups. In Guinea and Sudan, there is evidence of similar contestation between attempts to consolidate reform and civilian administration on the one hand, and incursion by the military into politics on the other. The fact that the AU has initiated suspensions 13 times against just six of its member states due to unconstitutional changes of government provides a clear indication of this pattern of incomplete transition in some countries. The countries in question are Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Egypt, Guinea, Mali and Sudan.

Second, there is some evidence to suggest a correlation between a country’s experience of a military coup and its socio-economic, governance and overall fragility contexts. Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, Sudan and Mali are ranked at the bottom of the UNDP Human Development Index. The HDI measures life expectancy, expected years of schooling, average years of schooling, and Gross National Income per capita. A low score indicates significant shortfalls in progress towards Agenda 2030 and Agenda 2063. These countries also rank low in the Mo Ibrahim Governance Index and are among the top countries in the Fragile States Index. Despite decades of development assistance, these countries are, in other words, still stuck in what some have called the ‘fragility trap’.

A related third set of drivers are citizens’ own desire for positive change, which relate to increased democratic aspiration on the continent and can inspire popular protest movements but also readily be instrumentalised by putschists. This is not to suggest that citizens’ perceptions justify military coups. Rather, it is evident from early findings of a new UNDP research project examining these issues, that prolonged frustrations and unmet expectations of citizens can serve to trigger popular support for any change of government, irrespective of whether it is through constitutional or unconstitutional means, at least in the short-term.

Incompleteness of previous transitions, underlying development and governance shortfalls and related citizen frustration emerge as salient factors shaping the trajectory of the countries that experience coups. They are experienced more widely across the continent however and cannot therefore be taken alone to explain coup occurrence.

A fourth set of factors to be considered is the sub-regional specificity of recent events. A concentration of the coups has played out in the greater Sahel. It is perhaps no coincidence that this is a region which has become increasingly militarised over the past decade. Since 2012 the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), French, United States (US) as well as regional forces have deployed at scale, responding to multiple intersecting crises such as terrorism and irregular migration.

Some analysts have long argued that investing in the region’s governance should be prioritised over and above the dominance of security approaches. The latter has sometimes raised the issue of the use indiscriminate force, which could erode state-citizen trust. Failure to reduce violence despite deployments has furthermore shaped the region’s political culture, with a leader’s ability to provide security seen as a priority.

At a time when competing global priorities are draining resources and shift attention away from Africa, focus and commitment is needed. At least four sets of priorities emerge:

Refocusing Sahel engagement

The upcoming AU – UN assessment of the Sahel offers a renewed opportunity for rethinking collective international support to national and local efforts for sustainable peace in the region. Some early results in the ongoing implementation of stabilisation in the Lake Chad Basin region, which contribute to the peace-development nexus provide inspiration. Reimagination of narratives about the Sahel, emphasising positive opportunities for growth and prosperity for its peoples should provide a foundation for new pathways for peace and sustainable development in the region. Vigilance on the conduct of security actors and scaling up governance priorities must be at the fore.

Ensuring timely responsiveness by partners to support inclusive political transition processes

Regional and international partners, including development agencies and financial institutions, need to demonstrate their readiness to support and sustain the ongoing transition processes underway on the continent – in and beyond the Sahel.Transition plans can harness opportunity for positive transformation through inclusive national dialogue. Economic and other levers that can incentivise political and military actors to meaningfully engage with citizens and to honour timeframes and commitments are a priority. Proactive and pre-emptive engagement is also critical to prevent further instances.

Deepening the quality of democracy

The sudden uptick in military coups over the past 24 months has sounded a dramatic warning note as to the welfare of African democracy, with some evidence of initial support for the coups in each of Burkina Faso and Mali. The current era has also seen an increase in leaders revising their constitutions, introducing extended term mandates in order to prolong and maintain power (what some have termed ‘constitutional coups’).

Taken together, these dynamics mark an overall shift towards an increasingly authoritarian context. More Africans now live under fully or partially authoritarian states today than has been the case over the past two decades.

Continued efforts to reconcile the gap between procedural and meaningful democracy are urgently needed.International development partners must reframe the wide basket of interventions designed to foster good governance, effective rule of law, security, justice and human rights and electoral democracy itself, taking limitations in achievement to date on board.

Leveraging the evolution and implementation of continental norms

The AU, as well as regional bodies such as ECOWAS, have played an important role in responding to the recent coups. The role of the AU is informed by the Lomé Declaration and normative frameworks including the African Peace and Security Architecture and African Governance Architecture. The predominance of the response by regional institutions has been through suspension of member states from the AU and/or ECOWAS.

The AU is also taking new initiatives to be better equipped to respond should there be further such instances – including, in partnership with UNDP, establishing a new Transitions Facility that will provide predictive analysis, support countries and enable regional institutions on inclusive transitions, grounded in a major forthcoming research study. Critical questions as to the implementation of norms, and the incentives of AU member states to adhere to them, have come urgently to the fore and require continued attention.

Jide Martyns Okeke, PhD, Coordinator, UNDP Regional Programme for Africa and Jessica Banfield, UNDP Senior Consultant