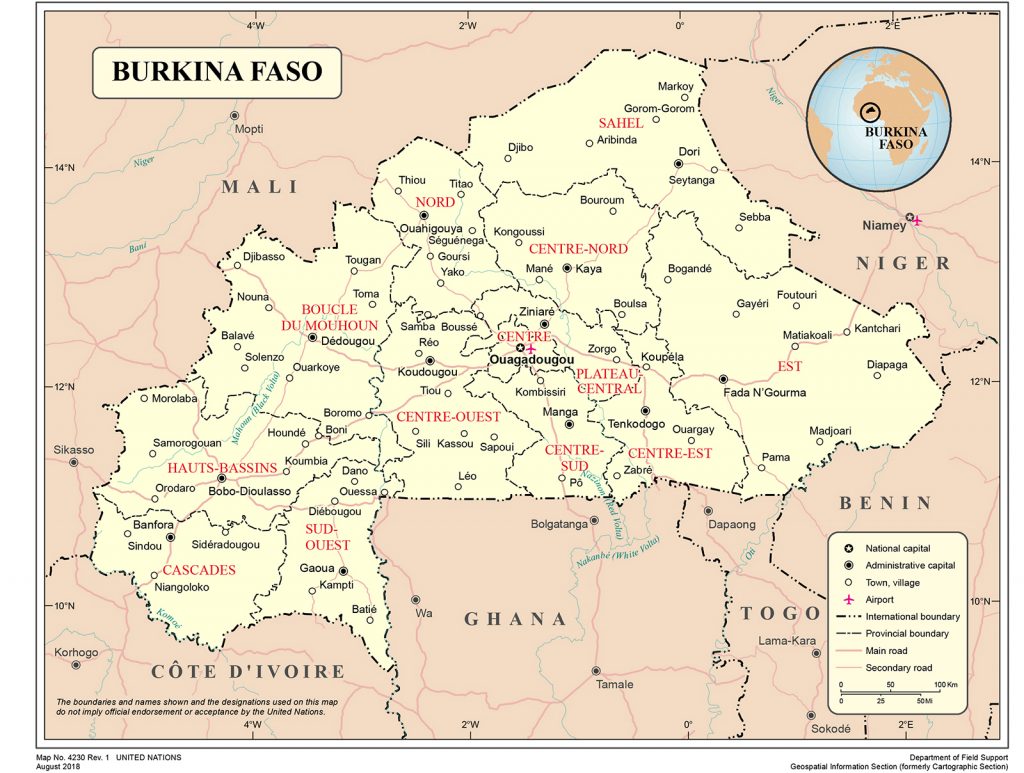

Burkina Faso has been engulfed in an ongoing conflict with jihadist insurgent groups active across the Sahel in West Africa. The conflict originally started in Mali in 2012 and later spread to Niger. In June 2021, the worst attack in Burkina Faso since 2015 occurred in the village of Solhan, where suspected jihadists massacred 160 civilians.[1]Naturally, discussions in the media revolved around who perpetrated the attack, but the attack also brought to the forefront the role of self-defence groups or militias in the Burkina Faso conflict. While the use of armed militias in Burkina Faso has become widespread and is actively sponsored by the State, there are concerns that self-defence militias perpetuate conflict. The main reasons are that self-defence militias in Burkina Faso are exacerbating mutual distrust, tension and violence among different communities, while the use and State sponsorship of militias are exposing the civilian population to reprisals from the insurgents who perceive them as a threat. The result is that President Roch Marc Kaboré may be doing more harm than good by creating self-defence militias under the legal framework of the Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland (VDPs) adopted unanimously by Burkina Faso’s Parliament in January 2020.

However, seen from the government’s perspective, its State Security Forces (SSF) are not scaled to cover the whole territory, and neither do the forces have the capacity (and sometimes the will) to deploy in vulnerable and remote areas rapidly and secure the civilian population. Even if the government wishes to expand the SSF and their capacities significantly, it does not have the resources.[2] As the SSF and international coalition forces proved unable to counter the increasing influence of jihadist insurgents in Burkina Faso, supplying civilians with weapons and training to create counterinsurgency militias can be seen as a pragmatic and resource-effective solution to combat widespread insecurity in the country’s conflict-affected areas. At least the government is seen to be doing something. However, more often than not, the use of militias to counter insurgencies perpetuates the conflict they initially set out to quell.[3]

Self-defence militias in Burkina Faso are part of the broader West African regional context where multiple and multifaceted militias have proliferated in recent decades. For example, during the civil war in Sierra Leone, the ‘invincible’ rebel group Revolutionary United Front was met with fierce resistance from the Kamajors militia and eventually lost the advantage in the war. The Kamajors are one of the more successful militias in Africa, as they improved the security of the people in the southeast parts of the country. However, they were also accused of human rights violations.[4] During a crime wave in Côte d’Ivoire in the 1990s, a group of hunters called Dozos formed the Benkadi movement and initially, they became a successful crime-fighting militia providing a nonpartisan form of public security. However, increasing entanglement with the State and political circumstances polarised the Dozos’ identity vis-à-vis the State, and in the end, some of them joined the rebel side in the Ivorian civil war.[5] In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni created Local Defence Units (LDUs) in conflict-affected provinces where the State fought the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Self-defence militias have a long history in Uganda, but the context changed with State sponsorship and tacit approval to orchestrate violence. The LRA interpreted the lack of popular support and enlistment for militias as indicating support for the government, and the strategy led to brutal attacks on civilians by the rebels. No consideration was given to the consequence of civilian involvement in counterinsurgency efforts; it was viewed as a case of self-inflicted harm caused by the State.[6] In Burkina Faso, the involvement of self-defence militias in counterinsurgency activities was more or less tolerated by the State until January 2020, when the new law called for volunteers to fight against the jihadist groups and legalised State-sponsored militias. This law constitutes a break in Burkina Faso’s history and calls into question whether counterinsurgency militias in the country are doing more harm than good and what the long-term consequences of weaponising the civilian population will be.

To discuss the use of militias in Burkina Faso, I utilise a framework for analysing militia violence that situates this case in a broader context of counterinsurgency ‘on the cheap’, or at a very low cost, in areas of violent conflict and fragile statehood.

How Militias Perpetuate Conflict

According to Schneckener, ‘militias [are] a special form of organised violence found in many civil wars and fragile states, and their formation is an indicator of a fragmented and highly politicised security sector under the circumstances of fragile statehood.’[7] Militias often claim to defend an established political or social order from internal and external threats, as opposed to rebels who are using violence to achieve revolutionary social and political change. This article uses Tisseron’s understanding of militias as ‘non-jihadist, armed actors which are supporting the state of Burkina Faso in its challenge to guarantee inner security for its citizens.’[8] As ideal types, the Burkinabé militias can be considered counter-crime or counterinsurgency militias depending on their objectives, which vary from location to location.

Schneckener argues that there are a few typical delegitimising effects associated with militia violence that over time become endemic in society and often perpetuate conflict:

- Militias are difficult to demobilise as their mission usually develops beyond their original purpose.

- The original stakeholders, such as elite sponsors, lose what control they initially had over the militia. State-sponsored militias risk developing into entities with social and political power beyond what the state is capable of reigning in.

- The ‘enemy’ of the militia often develops to include more targets, leading to unrestrained violence in an attempt to set an example for others who oppose or criticise the militia.[9]

In addition, militias put civilians at risk of becoming targets of reprisals by insurgents, as seen in Uganda.

From Counter-crime to Counterinsurgency

Local security initiatives have been common throughout Burkina Faso’s history, but since 2014, self-defence militias have proliferated across much of the territory. The absence of the State and insufficient provision of public security in a context of widespread crime has led to feelings of abandonment as well as revolts and the need to develop local security initiatives. In this context, a self-defence militia called the Koglweogo emerged as an endogenous alternative to the ineffectiveness of the SSF, and it largely reduced crime in several regions of Burkina Faso between 2014 and 2015.[10] The Koglweogo co-exists with a more long-standing group of hunters called the Dozo, who operate as a counter-crime militia and provide security in western Burkina Faso. In north-western Burkina Faso, the militia Dan Na Ambassagou, which is mostly active in Mali, has units and rear bases from which it is combatting jihadist insurgents. Together, this fragmented nature of different militias is part of a hybrid security environment, the forms of which vary from time to time and place to place, in a context where the State does not maintain a monopoly on the legitimised use of violence. Self-defence militias generally act as alternatives to an absent, ineffective or illegitimate State, both in cooperation and autonomously.[11]

The Burkinabé State deals with the militias with tolerance and pragmatism and provides a measure of leadership, but has struggled to bring them under its authority. The State attempted to bring the Koglweogo into a community policing initiative in 2016; however, the Koglweogo leadership refused to join the initiative.[12] The militia has also shown its willingness to enter into conflict with the State when its interests are threatened. In 2018, the Koglweogo surrounded a courthouse in Kaya to secure a member’s release.[13] This indicated that the militia’s social and political power had evolved beyond what the State is capable of controlling as it had indebted itself to the militias and given them free rein.

Counterinsurgency ‘on the Cheap’

Militias are a double-edged sword as they can help strengthen the State’s security network and support the SSF, but they also risk perpetuating conflict by exacerbating community tensions and violence.[15] As circumstances on the ground changed with the growing influence of jihadist groups in northern and eastern Burkina Faso, self-defence militias became involved in counterinsurgency operations, which was mostly tolerated by the State. The International Crisis Group warned against the perils of relying on militias for self-defence in Burkina Faso as they were upsetting the balance between different communities by mainly recruiting from the majority ethnic groups in their respective regions. For example, in the Centre-Nord, which has seen significant communal violence, the Koglweogo mainly recruit from the Mossi, the largest ethnic group in the region. This unbalance has fed into conflicts between farmers and herders to the detriment of the Fulani herder community. The Koglweogo, many of whom are sedentary farmers, have been settling land disputes in their favour and exploiting their relative power.[16]

The Koglweogo’s ‘enemy’ thus expanded to include the Fulani community as their primary targets in the Centre-Nord. The Fulani have been stigmatised as the main recruits for the jihadists, a similar process seen in central Mali. Threatened by the Koglweogo, the Fulani sought the protection of the Rouga, a group of Fulani herder representatives, whom the Koglweogo, in turn, perceived as ‘jihadists in disguise’. The conflict took on a communal dimension and created a climate of strong distrust.[17] The Koglweogo perpetuated the conflict with the jihadist groups, which culminated in two massacres. On 31 December 2018, unidentified gunmen killed six people in Yirgou, including the Mossi village chief and his son. In retaliation, the Koglweogo killed between 100 and 200 Fulani civilians.[18] In March 2019, a second massacre was perpetrated by Fulse, also recruited by the Koglweogo, against the Fulani in Arbinda (Soum), bordering the Centre-Nord.[19] Since then, several smaller attacks on Fulani communities have been perpetrated by the Koglweogo and the VDPs, resulting in the Fulani approaching the jihadists to seek protection or exact revenge. The deteriorating situation in the Centre-Nord and elsewhere largely benefits the insurgents in extending their influence and perpetuating conflict.

The establishment of State-sponsored militias and the VDPs has raised fears of communal violence occurring in other regions of Burkina Faso. First, as the call for VDP recruits mainly resonates within existing local security initiatives, such as the Koglweogo, the State risks reproducing and exacerbating communal divisions. The more neutral stance taken by the Koglweogo’s leadership changed with the establishment of the VDPs, and they encouraged their men to enlist. Second, by using poorly trained counterinsurgency militias in counter-terrorism operations, the State risks sanctioning the targeting of ordinary civilians who are conflated with jihadists by the militias and thereby exacerbating communal violence. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), VDP groups have been involved in 40 acts of violence against civilians since February 2020, and some of them involve extrajudicial killings of Fulani civilians.[20] This means that VDP counterinsurgency activities echo the trajectory of the Koglweogo with retribution and settling of scores. If the VDPs are not sufficiently supervised, they can do whatever they want under the guise of fighting terrorism.

Self-inflicted Harm – When Communities Take Sides and Become Targets of Violence

The creation of State-sponsored militias which recruit civilian volunteers from villages and peri-urban neighbourhoods seems to be perceived by the jihadists as an act of choosing to side with the Burkinabé State. According to Savadogo, the jihadist groups have waged open warfare against the VDPs.[21] ACLED has recorded 113 battles between jihadist insurgents and VDPs, including a number of ambushes on VDP positions.[22] For example, in November 2020, ISGS claimed responsibility for an attack killing at least eight VDP fighters at a mining site in the Soum region.[23] The VDPs regularly claim to be successful in repelling attacks, but the resistance is taking its toll and generates discontent. Following the death of three VDPs in Niagré in the East region in September 2020, demonstrators brought the bodies to the authorities in Fada N’Gourma to express their anger. According to Tisseron, some VDPs have ended their involvement due to threats against communities setting up self-defence militias.[24] This has also occurred among the Koglweogo groups in the East. It shows that self-defence militias do not necessarily represent the rapid strengthening of Burkina Faso’s security network, as was hoped.

Furthermore, the VDPs have exposed the civilian population to reprisals. In October 2020, the United Nations (UN) reported that 25 men in the north-central province of Sanmatenga were executed by an armed group whose members had allegedly identified themselves as jihadists. The killings were a reprisal for the presence of VDPs in the village.[25] In May 2021, presumed JNIM or ISGS militants killed four people in the village of Takatami. The victims were family members of young people who enlisted in the VDP. In the case of the Solhan massacre in 2021 mentioned above, the attackers targeted a volunteer fighter (VDP) position and mining sites, as well as the neighbouring villages of Mossiga and Gountoure. According to Tanguy Quidelleur, a researcher in politics and social sciences, the civilians were massacred because they were considered complicit.[26] The cycle of vendettas is similar to what has been observed in the Mopti region of Central Mali between the Fulani and Dogon communities. However, the massacre may also be linked to an ongoing conflict between JNIM and ISGS, and so one should be careful to consider the attack merely a reprisal against civilians who dared to create a self-defence militia.

VDP recruitment represents a nationwide blurring of the distinction between civilians and the military and mimics a similar dynamic seen in Nigeria, where the establishment of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) exacerbated violence against civilians.[27] Civilians were caught in a difficult position when jihadists considered villages with CJTFs as their enemies, while Nigerian security forces perceived any refusal to establish a CJTF unit as a sign of support for the jihadists.

Conclusion

Burkina Faso shows worrying indications of the tendency of militias to perpetuate conflict over time. The use of counterinsurgency militias may be doing more harm than good, as jihadist insurgents seem to target the VDP and their communities in brutal reprisals for choosing to side with the State. In other words, civilians have become targets of insurgent violence due to their perceived affiliation with State-sponsored militias, similar to what happened in Uganda with the LDUs who faced brutal reprisals from Joseph Kony’s LRA. At the same time, the activities and conduct of the VDPs echo the trajectory of the Koglweogo regarding the stigmatisation of the Fulani ethnic group. The result is that civilians are conflated with jihadists, leading to unlawful killings. The effect is the same as with harsh counter-terrorism operations carried out by the military and gendarmes in which targeted communities are forced to flee or seek protection due to indiscriminate violence. The State’s policies on self-defence militias can therefore exacerbate distrust and insecurity between communities, undermining its own efforts to combat violence and insecurity.

Viljar Haavik is a PhD candidate at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs focusing on non-state armed actors, violent extremism, and state-building.

Endnotes

[1] Dekimpe, Valérie (2021) ‘At Least 160 Killed in Deadliest Attack in Burkina Faso Since 2015’, Available at: <https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210605-dozens-of-civilians-killed-in-attack-on-northern-burkina-faso-village> [Accessed 10 June 2021].

[2] Kibora, Ludovic and Traore, Mamadou (2017) ‘Towards Reforming the Burkinabe Security System?’ Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Available at: <https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/programmes/observatoire-du-monde-arabo-musulman-et-du-sahel/publications/en/15.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2021].

[3] Schneckener, Ulrich (2017) ‘Militias and the Politics of Legitimacy’, Small Wars and Insurgencies, 28(4-5), 799–816.

[4] Muana, Patrick K. (1997) ‘The Kamajoi Militia: Civil War, Internal Displacement and the Politics of Counter-insurgency’, Africa Development, 22(3/4), 77–100; Braathen, Einar; Bøås, Morten; and Sæther, Gjermund (2000) Ethnicity Kills? The Politics of War, Peace and Ethnicity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

[5] Hellweg, Joseph (2011) Hunting the Ethical State. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[6] Omach, Paul (2010) ‘Political Violence in Uganda: The Role of Vigilantes and Militias’, The Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies, 35(4), 426–449.

[7] Schneckener, Ulrich (2017) op. cit.

[8] Tisseron, Antonin (2021) ‘Pandora’s Box. Burkina Faso, Self-defense Militias and VDP Law in Fighting Jihadism’, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Centre, Available at: <https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/fes-pscc/17590.pdf> [Accessed 10 August 2021], p. 4.

[9] Schneckener, Ulrich (2017) op. cit.

[10] International Crisis Group (2020) ‘Burkina Faso: Stopping the Spiral of Violence’, Available at: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/287-burkina-faso-sortir-de-la-spirale-des-violences> [Accessed 10 June 2021].

[11] Tisseron, Antonin (2021) op. cit.

[12] Hagberg, Sten (2018) ‘Beyond Regional Radars: Security From Below and the Rule of Law in the Sahel’, South African Journal of International Affairs, 25(1), 21–37.

[13] International Crisis Group (2020) op. cit.

[14] Dabiré, Angelin (2016) ‘Simon Compaoré, Président National des Koglwéogo en Tournée’, LeFaso, Available at: <http://lefaso.net/spip.php?article70817> [Accessed 15 August 2021].

[15] Tisseron, Antonin (2021) op. cit.

[16] International Crisis Group (2020) op.cit.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Jeune Afrique (2019) ‘Burkina Faso: Le Bilan de l’attaque de Yirgou s’alourdit et Passe de 13 à 46 Morts’, Available at: <https://www.jeuneafrique.com/698033/politique/burkina-faso-13-tues-dans-une-attaque-suivie-de-represailles-intercommunautaires> [Accessed 12 August 2021].

[19] Amnesty International (2020) ‘Burkina Faso: Witness Testimony Confirms Armed Group Perpetrated Mass Killings’, Available at: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/03/burkina-faso-witness-testimony-confirms-armed-group> [Accessed 12 August 2021].

[20] Raleigh, Clionadh; Linke, Andrew; Hegre, Håvard; and Karlsen, Joakim (2010) ‘Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset: Special Data Feature’, Journal of Peace Research, 47(5), 651–660.

[21] Sauvage, Grégoire (2021) ‘Burkina Faso: Islamist Groups Target Civilians in “Cycle of Vendettas”’, France24, Available at: <https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210607-burkina-faso-islamist-groups-target-civilians-in-cycle-of-vendettas> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

[22] Raleigh, Clionadh; Linke, Andrew; Hegre, Håvard and Karlsen, Joakim (2010) op. cit.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Tisseron, Antonin (2021) op. cit.

[25] Mednick, Sam (2020) ‘UN Says Attack in Burkina Faso Kills 25 People’, AP News, Available at: <https://apnews.com/article/burkina-faso-archive-united-nations-ouagadougou-44bbd9fe69583d4ade991830fad1de4b> [Accessed 22 August 2021].

[26] Sauvage, Grégoire (2021) op. cit.

[27] Tisseron, Antonin (2021) op. cit.