Introduction

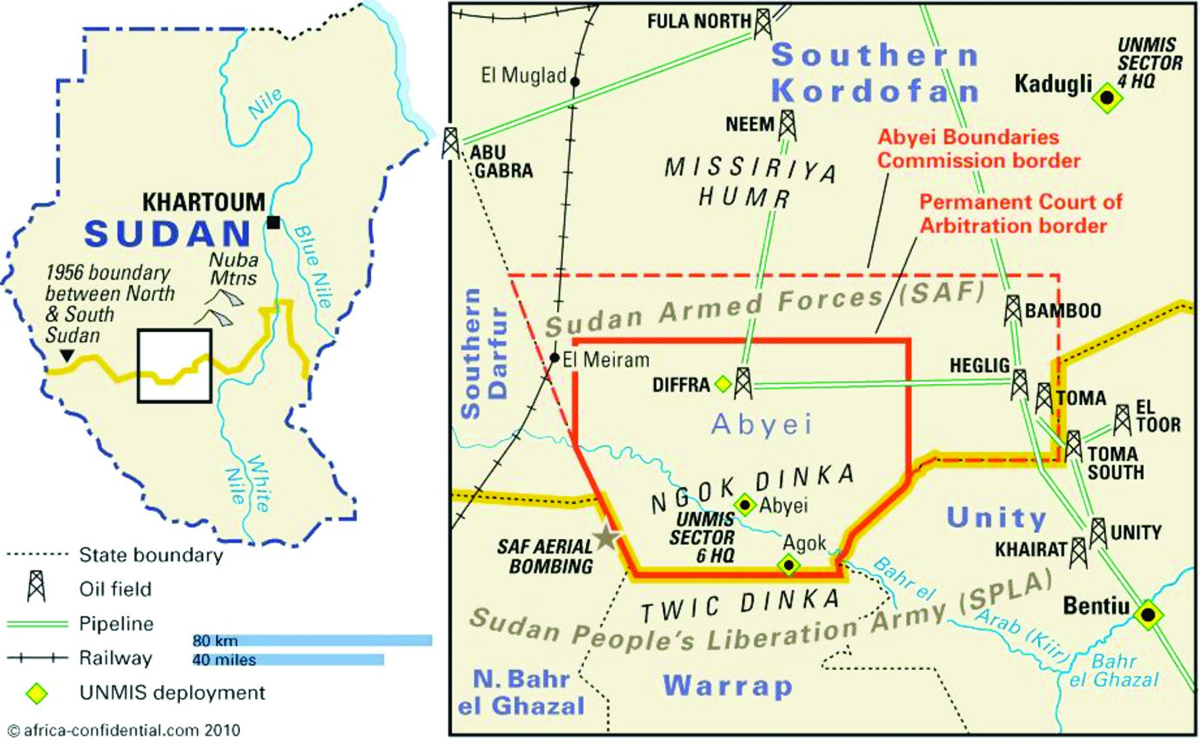

The Sudanese region of Abyei currently sits at the centre of a conflict between the north and south of what was Africa’s largest state. While analysts have described the situation in Abyei as “an intractable conflict”, this policy brief examines the current impasse, its historical context and the options available for breaking the deadlock and forestalling further conflict. The stalemate in the region has shown itself capable of pushing the two sides to full scale conflict as witnessed on 21 May 2011 when the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) launched a coordinated attack on South Sudanese military personnel in the contested region of Abyei. Sudanese President General Omar Bashir also unilaterally dissolved the joint North-South Abyei Administration; in addition to being unconstitutional the move serves only the further inflames tensions in the region. Khartoum claimed the assault was in retaliation for the killing of 22 SAF soldiers by South Sudanese military forces in the region. The current crisis emerges in large part from the intransigence of the parties and the inability of the international community to convince the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) that they can prevent further reneging on agreed issues by the National Congress Party (NCP).2 Additionally the non-implementation of Abyei Protocol, the Abyei Borders Commission (ABC) report – and now the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling – undermine other key aspects of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and set a worrying precedent for future agreements. This has created great suspicion and insecurity on the part of the SPLM. This insecurity has changed the trajectory of the Abyei conflict from a negotiation over shared rights to a zero sum game. Senior SPLM officials have expressed concern that representatives of the United States government are pressuring the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) to accept the possible partition of Abyei. High ranking SPLM officials also believe that this is the option increasingly favoured by the African Union and its High Level Implementation Panel (AUHIP) headed by ex-South African President Thabo Mbeki. While partition of the contested region may appear at first glance to be an optimum decision, the prospect of such a settlement has been deeply counter-productive, working to convince the Government of the Sudan (GoS) in Khartoum that it has more to gain through diplomatic intransigence and continuing turmoil in Abyei than the prompt and full implementation of the PCA ruling on the region as handed down on the 22 July 2009.

Anatomy of a Conflict

Abyei has since 1905 politically and administratively straddled the North and South of Sudan. Physical control of the area offers very little tactical advantages to either side in fact its historical and political significance far outweigh the region’s economic or strategic value. Abyei’s only permanent residents and primary inhabitants are the Ngok section of South Sudan’s largest ethnic group, the Dinka. The region also plays host to Arabic speaking nomads from the Humr section of the Misseriya of Kordofan. The latter herd their cattle into Abyei en route to pastures and water sources some 75 km south of the disputed territory during the December to April dry season. The timing, route and other technical issues related to this migration were in the past regulated by the chiefs of the nine Ngok clans and the Nazirs or paramount rulers of the two sections of the Misseriya, the Humr and the Zuruk. Relations between the Ngok and Humr have varied over time, with the Ngok suffering from Humr slave raids and Humr cattle subjected to rustling by the nine Ngok clans.

In 1905 the British began cementing the process of creating a cordon sanitaire between the north and the south. The process was designed to insulate the latter from the “culturally corrupting” influence of Arab culture and Islamic faith, illustrating British colonial fixation with discrete cultural groups and containing the spread of Islam, particularly in Western Bahr Al Ghazal. Thus, in 1905 British colonial administrators transferred the Abyei region to Northern Sudan’s then Kordofan province. At the time it was argued that this arrangement was administratively more convenient than controlling the area from the southern province of Bahr el Ghazal, as it was cut off from the provincial capital for long periods during the rainy season. The rationale was also to place the Humr and Ngok under the same provincial authority and jurisdiction to deal with cattle and slave raiding.3 The transfer took place without consulting the predominantly Dinka Ngok population of Abyei. The actual size of the territory transferred is at the root of today’s crisis, as British colonial dispatches refer to Abeyi, or the area of the nine Ngok chiefdoms, but never specified its actual boundaries.

Several border shifts and territorial transfers similar to the one involving Abyei took place between the north and south and sowed the seeds of many border disputes currently hindering cordial relations between the two Sudans. This process of boundary changes reached a climax in 1922 when colonial officials forcibly evicted the entire population of the Kafia Kinga enclave in an attempt to create a “a tangible division between ‘Arab’ and ‘African’ groups along the border zone between Darfur and Bahr Al Ghazal”.4 The region, which had previously been a melting pot of cultures, became an impenetrable barrier. In 1958 the military regime of General Ibrahim Abboud annexed the Kafia Kingi enclave to Darfur.

A similar transfer occurred in 1924 when the Munroe-Wheatley agreement changed the border between the Rizegat of Darfur and the Malwal Dinka of Bahr al Ghazal. The border between the two communities and the provinces they inhabited previous lay at the banks of the river Kiir known in the north as the Bahr al Arab. However, the agreement shifted the boundary 14 miles, or 22 km south, of the river. The agreement was designed to allow the Rizegat, who the British were attempting to woo as allies, greater access to the rich grazing lands just south of the river and reduce conflict between them and the Malwal Dinka who inhabited the area. This border shift was implemented without the authorization of the Governor General in Khartoum and without consulting the Dinka at the time. As a result the agreement is currently contested by the GoSS, while Khartoum argues that since it took place before 1956 the border is not subject to alteration.5

When seen in this light, the transfer of Abyei was one of several boundary adjustments by British colonial officials which have left a lasting impact on relations between the two Sudans. While much of the media and policy focus has been on the relations between the Ngok and Humr, the problem and solutions to the current conundrum lie at a higher level, namely Juba and Khartoum.

Who are the Misseriya

Though their territory is currently at the centre of the crisis very little is known about Ngok and in particular the Humr. The Humr are actually one section of the Misseriya that reside in Kordofan, the other being the Zuruk. While the Abyei dispute is often described as a primordial conflict between the Ngok and the Misseriya, this is in fact inaccurate, since only one section of the later is actually involved. The current dispute revolves around the inclusion of the Misseriya as voters in the referendum on the final status of Abyei. Their inclusion is challenged by the GoSS, who argued that with the exception of the 25 000 nomads who spend a longer period than others in Abyei and the South, the Misseriya as a whole are not eligible to vote. The GoS on the other hand claims that all of the estimated 300 – 400 000 Misseriya must be allowed to vote if the referendum is to go ahead. The reasoning behind this is simple. If the 400 000 Misseriya are allowed to vote in the Abyei referendum then their numbers will swamp the 70 000 or so Ngok Dinka and secure the region for Khartoum. However, one key fact about the Misseriya that is often overlooked is that all the Misseriya do not migrate through Abyei during the dry season. The Humr are divided into two main groups the ‘Ajaira and the Felaita. The former have six sub-groups of which only four migrate via Abyei, with other sections crossing via Unity State or Northern Bahr Al Ghazal. These nomads number approximately 15 000 – 25 000 and would have little impact on the results of referendum.6

| The Humr, like all Baggara or cattle Arab groups, have their origin in hybridization of Arab and Fulani modes of production in the Lake Tchad Basin.7 As Arab and Teda speaking camel nomads migrated south from Libya and via northern Tchad, they came into contact with Fulani nomads who were slowly filtering through the Lake Tchad basin as they spread out from their home region in Futo Toro Senegal. The camel nomads forces to abandon camels, whose delicate feet could not deal with the damp conditions, shifted to cattle and adopted many of the Fulani husbandry practices – while the Fulani gradually adopted the Arabic language – the result was a new social group the Shua or Baggara Arabs, who rapidly filtered east from their home region around Lake Tcahd. The Misseriya themselves spread east from Salaamat river area in Tchad and arrived in Abyei a few decades after the Dinka region, sometime around 1730-40s via Ouaddai and Darfur.8 As a result there are several smaller pockets of Misseriya in the Darfur area as well as in Tchad, these include the Salaamat of Tchad, Misseriya of Kas to the west and south of Kas town, the Jabaal or Mileri of Jebel Moun who claim Misseriya heritage, as well as several sections of the Zaghawa of Dar Galla in the Kornoi area. Additionally several smaller Baggara groups in Darfur have become clients of local Misseriya. The various sections of the Misseriya though united by a common history are politically independent. Thus, in the Sudan the term Misseriya is usually used to cover the Humr and the Zuruk and at other times all Misseriya sections. This process of ethnogenesis is common among the Baggara and caused British colonial officials some problems when it came to administration in Baggara areas. In order to deal with shifting alliances and ethnic affiliation, the British went as far as holding fragmenting Baggara groups together, sometimes against their will. For instance, they moved the two subgroups of the Beni Hussein to their present home north of Kepkabia and united the two sections of the Beni Halba, though these had been diverging both geographically and politically for some time.9 As the Humr and Zuruk also began to diverge the British tried, and failed to hold them together, eventually each section got its own Nazir or paramount chief. |

Another central point that is often overlooked in the Abyei conflict is that Abyei itself is not the final destination of Northern nomads and their herds. The Humr actually only pass through Abyei on their way some 75 km south of the region, thus retaining control of the contested region does not actually befit the Humr in the long run, since other Dinka sections have stated that without a solution to the problems in Abyei, the Misseriya as whole will not be allowed into the territory of the Twic, Ruweng or Malwal Dinka.10 In fact none of the other Misseriya sub-groups meet the residency requirements that would allow them to take part in the referendum. Having argued and in some ways won the case for a smaller Abyei, the GoS has accidentally ensured that their allies, the Humr, are unable to take part in the now delayed referendum.

The Long Road to the Current Impasse

While interactions between the Ngok and the Humr were not always peaceful, they were at least stable and predictable. This all changed with Sudan’s first civil war (1956 – 72) with relations between the two groups turning to open conflict during the second civil war (1983 – 2005). Tensions between the two communities were exacerbated as the Ngok Dinka became key members of the SPLM, while the Misseriya became clients of the north, with many eventually joining government-backed militias. Abyei was a key battleground during the civil war, as it formed a key crossing point for pro-Khartoum Misseriya militias. As a result of the conflict tens of thousands of inhabitants, mostly Ngok Dinka, were displaced.

The final status of Abyei was one of the most contentious issues in the lead up to the CPA. However, since the 2002 Machakos Protocol defined ‘Southern Sudan’ as it existed at the time of independence in 1956, Abyei was not included.11 The SPLM and the NCP were at loggerheads over the small territory and the issue was not resolved until the Protocol on the Resolution of the Abyei Conflict12 designated the area a special administrative status, governed directly by the presidency. The exact borders of the region at the time of independence were to be investigated and made public by a panel of experts know as the Abyei Borders Commission (ABC). The ABC was tasked to define the Ngok Dinka territory as it had been one hundred years prior, in 1905. This would be followed by the establishment of a referendum commission to identify who was eligible to vote in a referendum on the status of the region which would run concurrent to the referendum in the South on independence.

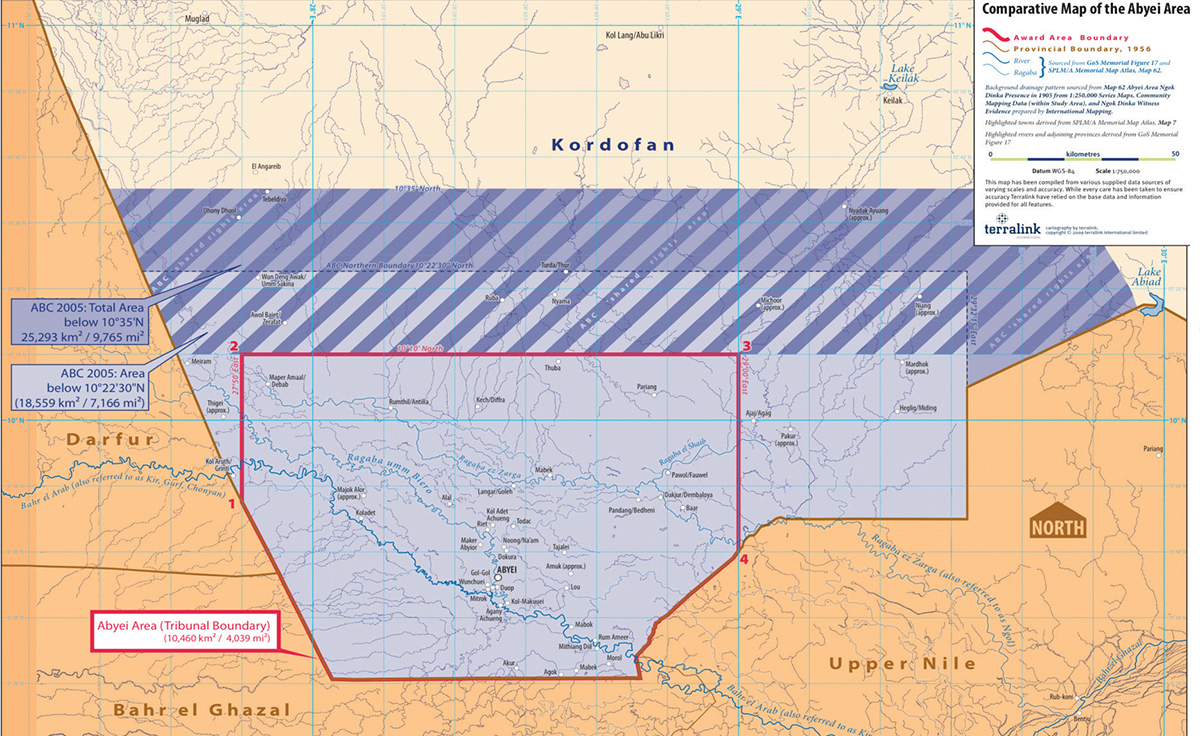

The ABC issued what was supposed to be a “final and binding” ruling on Abyei’s boundary in July 2005. The ruling set the boundary of the Abyei region 87 km north of Abyei town. The area included all villages recently inhabited by Ngok Dinka; however areas from which the Ngok had been forced to flee and had been occupied by the Humr were placed in a zone of shared rights.13 The GoS rejected the ruling, claiming that the ABC exceeded its mandate and a three-year stalemate ensued. Since this time Abyei has been the source of direct clashes between the SPLM and northern backed militias, and later Sudanese army troops in 2007. The dispute erupted into violence in May 2008, when Abyei town itself was razed to the ground, causing the majority of the towns 60 000 inhabitants to flee south.14

On 8 June 2008 the NCP and the SPLM signed the Abyei Roadmap Agreement15 aimed at breaking the deadlock on implementation of the Abyei Protocol. The two parties also agreed on 21 June 2008 to refer the dispute over the Abyei boundaries to the PCA, which rendered its decision a year later on 22 July 2009. The PCA ruling reduced the size of Abyei considerably, did away with the ABC zone of shared rights and placed most of the contested oilfields in Kordofan (i.e. in the North) and not in Abyei. The PCA defined the region as the area of permanent Ngok settlement and also contended that intent of the Abyei Protocol was to empower the Ngok Dinka as a whole to choose their status as Northerners or Southerners in a referendum. On paper the ruling gave Khartoum much of what it wanted – control of the oil fields in the north-east corner of the ABC award and, by focusing on the area of ‘permanent’ Ngok habitation, it additionally excluded much of the area settled by the Misseriya during the war from the new Abyei region.16

However, while the GoSS accepted the decision the GoS rejected the ruling, with a senior NCP member stating that it “did not satisfy the needs of the two partners” and that “the two partners must find new solutions”.17 Senior GoS officials expressed similar opinions, stating that to the NCP the CPA is an agreement between the NCP and the SPLM and can be renegotiated. However for the SPLM the CPA is a legally binding document that should be implemented in its entirety. The international community, led by the African Union High Level Panel, has so far been unable to persuade Khartoum to adhere to the binding nature of this (the second) round of arbitration over the disputed area.

More at Stake than Grazing Rights or Oil

Following the PCA ruling, the borders of Abyei should have been demarcated and registration for the referendum begun. However, Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) personnel and Humr militias prevented the survey teams from laying boundary markers, claiming that unless the Misseriya were allowed to vote in the referendum demarcation could not commence.18 Unverified claims by GoSS officials and local Ngok leaders accuse GoS of settling Misseriya in the PCA award area in an attempt to change demographic realities on the ground.19 UNMIS officials have complained that they do not have full access to the region, which has witnessed a build-up of troops and heavy weapons from both the North and South.20

Abyei as defined by the ABC had three productive oil fields: Heglig in the east, Bamboo in the northeast and Diffra in the north. After the announcement of the PCA decision in July 2009 and the reduction of the size of the Abyei area only one field, Diffra, fell within the boundaries of Abyei, with Bamboo and Heglig now in the Northern state of South Kordofan. In the early 2000s the combined production of the three fields was in the vicinity of 76 600 bpd, approximately 25% of the Sudan’s oil production.21 However the production rates of the three fields have declined considerably since then – from the 76 600 bpd of 2004 to 28,300 bpd in 2009 – and as production in the rest of the South increased Abyei’s share of national production fell to less than 5%.22 Diffra, the only field currently in the Abyei areas as defined by the PCA, produced less around 4 000 bpd in 2009 – less than 1% of Sudan’s national output.23 Much of the decline is simply due to the fact the fields have peaked and are now in decline. Thus, the description of Abyei as “oil rich” is both overstated and serves to mask the more deep seeded issues causing the impasse.

With the NCP unwilling to lose Abyei and alienate the Misseriya, the current stalemate may continue up to 9 July 2011 unless the AUHIP can help steer the parties into an agreement. The SPLM, having seen that the AUHIP and international community are unable or unwilling to hold Khartoum to international agreements, may attempt to recover Abyei by force. The GoS President General Omar Bashir recently threatened a return to war if Abyei did not remain a part of the north.22 GoSS has also upped the ante by including Abyei as a part of South Sudan in their draft constitution23

Recommendations

To the Parties

- SAF forces must be withdrawn from the PCA defined Abyei area.

- The dissolution of the Abyei Administration is in direct violation of the interim constitution of the Sudan which states that all appointments in the region must be made by Presidency – a body that includes the Presidents of both the North and South.

- During the run up to the referendum on the independence of the South, the GoSS made a concerted and commendable effort not to be dragged back into conflict in spite of numerous provocations and CPA infractions. Similar restraint must now be exercised on Abyei.

- In order to prevent an increase in tension and the possibility of full scale war GoS and GoSS should step up efforts to implement the Abyei Protocol and other outstanding aspects of the CPA related to the disputed territory before 9 July 2011.

- Both parties must make credible and legally binding commitments to the Humr and other Baggara groups that cross the border, that their right to migrate to the south will be respected.

- The PCA ruling confirms the right of ‘residents’ of Abyei to vote in a referendum and as such Humr Misseriya that migrate through Abyei have the right to vote in the referendum – not the Misseriya community as a whole. GoS needs to begin the process of registering nomads from the four ‘Ajaira sections, based on tax rolls, so they can participate in the election.

- Failing this Abyei should be transferred from the North to the South by presidential decree. The referendum on the status of Abyei was meant to be held concurrently with the referendum on independence for the South – the logic being that Abyei was voting to join the South, which may or may not vote for independence. At the time of the writing of this brief, the referendum has been postponed due to a dispute over registration of the Misseriya as residents of Abyei and their eligibility to vote. One way around this impasse would be for the region to be transferred to the South Sudan by presidential decree and thereby skip a referendum, the outcome of which is a foregone conclusion. This transfer could take place after an agreement is reached on right of the ‘Ajaira section of the Humr to access to the territory in South Sudan during their annual migrations.

To the AUHIP

- Recent suggestions that partition may be the only viable solution to the current crisis are counter-productive and have made a sustainable solution less, rather than more likely.

- Additional territorial compromises in Abyei only serves to reinforce the notion that there is more to gain through diplomatic intransigence and continuing turmoil in Abyei than the prompt and full implementation of the PCA ruling on the region as handed down on 22 July 2009.

- The AUHIP should use it good offices to persuade the GoS and GoSS to carry out the full implementation of the PCA ruling.

- The AU and AUHIP should also work to establish credible mechanisms to facilitate the peaceful migration of nomads through Abyei and other border areas. This mechanism should include conflict prevention, early warning instruments and a conflict mitigation program.

- President of GoSS, Silva Kiir, has personally expressed his willingness to contribute to a development fund for Humr lands if Abyei is transferred to the South. In his own words “the problem of the Misseriya is not of pastures and water, but is one of underdevelopment”.24 While President Kiir has ruled out a 50-50 split of the South’s oil wealth, he has indicated he is willing to contribute to a joint fund for the development of Humr areas if Abyei is transferred to South Sudan. The AUHIP should investigate the feasibility of establishing a joint fund with contributions from GoS, GoSS and the international community to improve water management and cattle husbandry techniques on both sides of the river Kiir. This would reduce the dependence of nomads on the river Kiir and also reduce tensions and violent confrontation in the region.

Conclusion

For the GoSS, Abyei is the first and should have been the least complicated of six contested border areas. The prospect of a loss of, or an even further truncation of Abyei sets a troubling precedent for the negotiation over the Kafia Kinga area transferred to Darfur in 1960, the Safaha area which was transferred from Bahr al Ghazal to Darfur in 1923, as well as the Renk, Kaka and Magenis areas whose borders were altered by successive northern governments after independence. The GoSS regards Abyei as an area that has already been partitioned when compared to the initial ABC report recommendation.

For the GoS Abyei is an area that must be kept at all costs. The Misseriya, hitherto earnest allies of the Khartoum government, need to be kept on side, and losing Abyei to South Sudan would damage the already strained relationship. As the largest Baggara group with a history of service as a government proxy militia, Misseriya demands carry weight in the security apparatus that dominates the GoS. It is clear that the GoS hopes to use Abyei as a bargaining chip in their negotiations with South Sudan over other unrelated issues. Senior GoSS officials have stated that Khartoum has proposed that Abyei could be transferred to the South by presidential decree before 9 July if the 50-50 wealth sharing deal related to oil in the entire South is extended for another 10 years – something that the South is unwilling to consider at this point in time, especially with the PCA ruling confirming that the residents must be allowed to choose between Khartoum and Juba.

Leading figures in the GoS have expressed their frustration with the North and the AUHIP and have stated publically and privately that partition is not an option and that a return to war for the region is not impossible. These statements along with the recent build-up of SAF and SPLM forces in the region suggest that both sides are preparing for further confrontation. With this level of insecurity and uncertainty the Humr sections from Kordofan have avoided Abyei and migrated south via Bahr Al Ghazal, where relations with the Malwal Dinka are somewhat better. They have not been allowed to cross via Abyei and officials and communities in Unity State have barred armed Misseriya from entering the region, which suffered heavily from Misseriya and Hawazama raids during the civil war. As a result of their late departure and long detour via Darfur to Bahr al Ghazal, Misseriya cattle are stressed and would have to stay longer than usual in Abyei to recover, adding to an already tense situation. For the GoS and the Humr the choices around Abyei are fairly simple: they can keep control of the territory in violation of international law and claim a small but in the end expensive victory, since the Humr will not be allowed into other areas of the south.

The likelihood of violent confrontation increases as the independence of the South approaches. If outstanding CPA issues are not resolved before separation the probability of a conventional interstate war will also increase. Additionally, failure to resolve the issues of Abyei will cloud both NCP and SPLM calculations about other outstanding CPA issues and most likely hamper further negotiations. Abyei should be seen as an international problem which can only be addressed within the confines of international law. Thus, Abyei must be considered in a wider context as a national issue between North and South not just a local problem between the Humr and Ngok and their backers in Khartoum and Juba. Therefore any recommendations must be aimed at the national capitals rather than just at the local level and be based on the latest understanding of the current political assemblages both nationally and internationally. While the options for achieving a peaceful resolution to the crisis in Abyei may differ, the outcome must be the same – the Ngok must be allowed to express their right of self determination as enshrined in the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, the Machakos Protocol of 2002, the CPA of 2005 and the PCA ruling of 2009.

Bibliography

- Amanda Hsaio, Sudan Official: Misseriya Settling In Abyei, Fueling Referendum Tension, 4 August 2010, Available at <http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/sudan-official-misseriya-settling-abyei-fueling-referendum-tensions>

- BP, (2010), Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010, Available at <http://www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/globalbp_uk_english/reports_and_publications/statistical_energy_review_2008/STAGING/local_assets/2010_downloads/statistical_review_of_world_energy_full_report_2010.pdf>

- Charles Deng, Abyei Boundaries Commission Part 2, 22 November 2005, Available at <http://www.sudaneseonline.com/earticle2005/nov22-64940.shtml>

- de Waal, A. 5 Aug. 2004a. ‘Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap’. London Review of Books, Volume 26. Issue 15

- Douglas H. Johnson, The Road Back from Abyei, 14 January 2011. Available at <http://www.riftvalley.net/resources/file/The%20Road%20Back%20from%20Abyei%20by%20Douglas%20H.%20Johnson.pdf>

- Human Rights Watch, Abandoning Abyei: Destruction and Displacement, May 2008, 22 July 2008, Available at <http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4886e69a2.html> (accessed 27 April 2011)

- Jonathan Owens (ed.): Arabs and Arabic in the Lake Chad region. (Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, Bd. 14.) 312 pp. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 1994. DM 78.

- H.A. MacMichael, The Tribes of Northern and Central Kordofan (Frank Cass, London, 1967 [1912]), pp. 140–6

- International Crisis Group (ICG), Sudan: Breaking the Abyei Deadlock, N°47, October 2007. Available at <http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/files/africa/horn-of-africa/sudan/b047%20sudan%20breaking%20the%20abyei%20deadlock.ashx>

- Ian Cunnison, Baggara Arabs: Power and the lineage in a Sudanese nomad tribe, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1966,

- International Crisis Group (ICG), Sudan: Defining the North-South border, September 2010. <http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/horn-of-africa/sudan/B75%20Sudan%20Defining%20the%20North-South%20Border.ashx>

- Johnson, Douglas. (2008). Why Abyei Matters: The Breaking Point of Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement? African Affairs, Vol. 107, Issue 426, pp. 1-19, 2008. p4. Available at <http://www.cmi.no/sudan/doc/?id=944>

- Lathrop, C and Bederman, D. 2010. Government of Sudan v. Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (“Abyei Arbitration” The American Journal of International Law Vol. 104, No. 1 (January 2010), pp. 66-73

- Machakos Protocol, IGAD “Secretariat on Peace in the Sudan”, 20 july 2002, Available at <http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/IMG/pdf/IGAD.pdf>

- Opheera McDoom, Deadlock in dispute over Sudan’s Abyei oil region. Reuters, August 2010, Available at <http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/08/01/idUSMCD150582._CH_.2400>

- P.P. Howell, “Notes on the Ngork Dinka of Western Kordofan”, (1951) 32 Sudan Notes and Records 239,p. 242,

- Sudanese online, Sudanese media expert warns against Zionist plots targeting the Sudan; Dec 2010, Available at <http://www.sudaneseonline.com/en216/publish/Latest_News_1/Sudanese_media_expert_warns_against_Zionist_plots_targeting_the_Sudan.shtml>

- Sudan Tribune, Abyei Boundary Commission Report, July 2005, Available at <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article11633>

- Sudan Tribune, Foreign schemes” to divide country, Sudanese official alleges, 15 May 2005. Available at <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article9566>

- Sudan Tribune, Sudan President Al-Bashir threatens to wage war in South Kordofan, says Abyei will “remain northern”, 28 April 2011. Available at <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article38717>

- The Christian Science Monitor, Oil-rich’ Abyei: Time to update the shorthand for Sudan’s flashpoint border town? Available at <http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/Africa-Monitor/2010/1102/Oil-rich-Abyei-Time-to-update-the-shorthand-for-Sudan-s-flashpoint-border-town>

- The Draft Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan 2011

- United Union Mission in Sudan: Abyei Protocol Fact Sheet, February 2009, Available at <http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/Fact%20Sheets/FS-abyeiprotocol.pdf>

- United Nations Mission in Sudan, Abyei Roadmap Agreement Fact Sheet, June 2009, Available at <http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/Fact%20Sheets/FS-Abyei%20roadmap.pdf>

Notes

- Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge is a Senior Researcher in the Knowledge Production Department at ACCORD. He obtained a PhD in Anthropology from Durham University, UK and an MA in African Studies from Yale University, USA. Thanks go to colleagues in the Knowledge Production Department, Dr. Grace Maina, Salome Van Jaarsveld, Christy McConnell and Dr Martha Mutisi for their insightful review of this article.

- The SLPM is the dominant party in the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) based in Juba while the NCP is the dominant party in the Government of Sudan (GoS) based in Khartoum

- Johnson, Douglas. 2008. Why Abyei Matters: The Breaking Point of Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement?. African Affairs, Vol. 107, Issue 426, pp. 1-19, 2008. p 4. Available at <http://www.cmi.no/sudan/doc/?id=944>

- B.G.P./SCR/I.C.6, ‘Administrative policy, Southern Provinces’, 22 March 1930, Bahr al-Ghazal province governor Brock to Civil Secretary, reproduced in the collection British Southern Policy in the Sudan (nd)

- ICG. 2010. Sudan: Defining the North-South border. September 2010. <http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/horn-of-africa/sudan/B75%20Sudan%20Defining%20the%20North-South%20Border.ashx>

- Interview Misseriya academic.

- Jonathan Owens (ed) 1994. Arabs and Arabic in the Lake Chad region. (Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, Bd. 14.) Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Abyei Boundaries Commission Part 2 By Charles Deng, Available at <http://www.sudaneseonline.com/earticle2005/nov22-64940.shtml> P. P. Howell, ‘Notes on the Ngork Dinka of western Kordofan’, H. A. MacMichael, The Tribes of Northern and Central Kordofan (Frank Cass, London, 1967 [1912]), pp. 140–6; Ian Cunnison, Baggara Arabs: Power and the lineage in a Sudanese nomad tribe (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1966)

- de Waal, Alex. 5 Aug. 2004a. ‘Counter-Insurgency on the Cheap’. London Review of Books Volume 26. Issue 15

- Interview Twic Dinka elder.

- Machakos Protocol, IGAD “Secretariat on Peace in the Sudan”, 20 July 2002, Available at <http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/IMG/pdf/IGAD.pdf>

- United Nations Mission In Sudan, Abyei Protocol Fact Sheet, February 2009. Available at <http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/Fact%20Sheets/>

<FS-abyeiprotocol.pdf> - Sudan Tribune, Abyei Boundary Commission Report, 2005, Available at <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article11633>

- Human Rights Watch, Abandoning Abyei: Destruction and Displacement, May 2008, 22 July 2008, available at <http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4886e69a2.html> [Accessed 27 April 2011]

- United Nations Mission in Sudan, Abyei Roadmap Agreement Fact Sheet, June 2009, Available at <http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/Fact%20Sheets/FS-Abyei%20roadmap.pdf>

- Lathrop, C and Bederman, D. 2010. Government of Sudan v. Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (“Abyei Arbitration)” The American Journal of International Law Vol. 104, No. 1 (January 2010), pp. 66-73

- McDoom,O. August 2010. Deadlock in dispute over Sudan’s Abyei oil region. Reuters. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/08/01/idUSMCD150582._CH_.2400>

- Johnson, D. The Road Back From Abyei. 14 January 2011. Available at <http://www.riftvalley.net/resources/file/The%20Road%20Back%20from%20Abyei%20by%20Douglas%20H.%20Johnson.pdf>

- Amanda Hsaio, Sudan Official: Misseriya Settling In Abyei, Fueling Referendum Tension, 4 August 2010, Available at <http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/sudan-official-misseriya-settling-abyei-fueling-referendum-tensions>

- Interview UNMIS official.

- ICG, 2007, Sudan: Breaking the Abyei Deadlock, N°47, 12 Oct 2007. Available at <http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/files/africa/horn-of-africa/sudan/b047%20sudan%20breaking%20the%20abyei%20deadlock.ashx>

- The Christian Science Monitor, Oil-rich’ Abyei: Time to update the shorthand for Sudan’s flashpoint border town? Available at <http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/Africa-Monitor/2010/1102/Oil-rich-Abyei-Time-to-update-the-shorthand-for-Sudan-s-flashpoint-border-town>

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010, Available at <http://www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/globalbp_uk_english/reports_and_publications/statistical_energy_review_2008/STAGING/local_assets/2010_downloads/statistical_review_of_world_energy_full_report_2010.pdf>