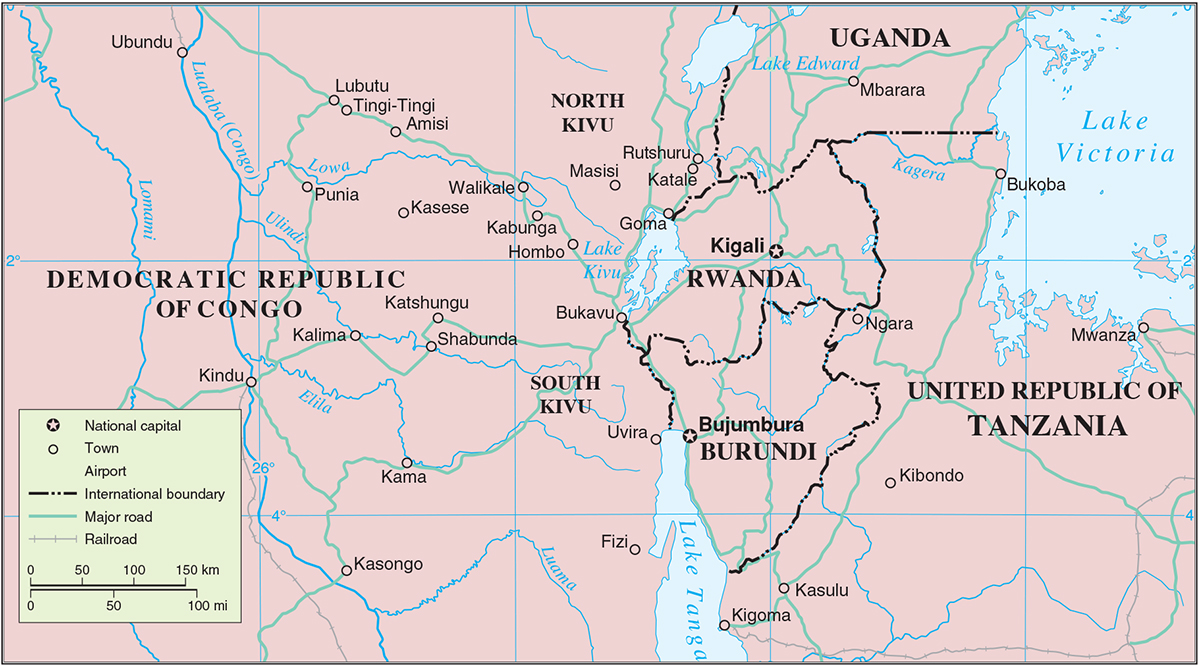

Since the 1990s the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has continued to be mired in intractable conflicts. Despite the establishment of an elected government in 2006 following the implementation of a series of peace agreements, the country still faces challenges in consolidating peace throughout its territory. The eastern regions of the DRC have consistently experienced high insecurity and repeated incidences of violence, often as a result of interference of neighbouring countries. The recurring episodes of violence in both the eastern and other regions of the DRC indicate that the process of conflict transformation is impeded by deep structural issues in society. These issues must be addressed if peace in the country, and the Great Lakes region, is to be achieved.

Introduction

Despite the fact that the DRC is wealthy in natural resources, vast populations continue to be politically and economically marginalised. Delivery of basic services and social amenities beyond the capital, Kinshasa, continues to be a challenge. Historical injustices contingent on the greed and manipulation of leadership structures that characterised the country’s colonial history, which spilled over into post-independence arrangements, have not been tackled and this has cultivated mutual suspicions among different ethnic groups. These issues, and others that will be discussed in this brief, need to be comprehensively addressed if conflict transformation in the DRC is to be realised. Conflict transformation here refers to changes in all, any, or some combination of the following matters regarding a conflict: the general context or framing of the situation, the contending parties, the issues at stake, the processes or procedures governing the predicament, or the structures affecting any of the aforementioned.2 A long-term process, conflict transformation is ultimately about changing individual attitudes and addressing the need for structural reforms.

The crisis in the DRC is a cause for concern which continues to dominate international discussion. The extremely violent and resource-driven nature of the conflict, massive displacement of people, as well as sexual and gender-based violence that characterises the conflict in the DRC continue to shock the world and to hold the attention of multiple actors. This is evident in the commitment of the African Union (AU) to formulate and adopt strategies to resolve the conflict. In 2005, the AU and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development worked on a post-conflict reconstruction framework which is structured around three broad phases: the emergency phase, the transitional phase and the developmental phase. Currently under implementation, this strategy is powered by multiple actors. Since 1999, US$ 8.73 billion have been spent to fund the United Nations’ (UN) peacekeeping efforts in the DRC.3 The UN has maintained its presence through the UN Stabilisation Mission in the DRC, whose mandate was renewed on 27 June 2012, placing emphasis on ensuring the protection of civilians. The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) has taken a regional stance to finding a lasting solution to the DRC crisis, noting that the emergency in the DRC is not only a threat to the country, but also to the peace and security of the entire Great Lakes region. It is important to note that whilst significant attention has been paid to the DRC by both regional and international actors, the humanitarian crisis and violence still continues. In spite of the numerous peace talks, elaborate peace processes and signed peace agreements, the DRC continues to experience high levels of human insecurity. This Policy & Practice Brief examines why peace has been so elusive in the DRC and offers recommendations that could contribute to the sustainable resolution of the current crisis.

Background to the conflict

The DRC has been deeply fractured by a conflict that can be divided into three parts.4 The First Congo War began in November 1996 and ended with the toppling of President Mobutu Sese Seko in May 1997. In this war, Angola, Rwanda and Uganda formed a coalition against the DRC forces. After a brief lull in the fighting, the new president, Laurent Kabila, fell out with his Rwandan and Ugandan allies who had been instrumental in ousting the Mobutu regime and installing Kabila in power. This falling out sparked the Second Congo War which began in August 1998. The second war was characterised by the participation of many actors in complex alignments. Some joined the war in support of Kabila, whereas others joined to seek to oust him. On one side there was Angola, Chad, the DRC, Namibia, Sudan, Zimbabwe and the Maï-Maï and Hutu-aligned forces. On the other side there was Burundi, Uganda, Rwanda and the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) and Tutsi-aligned forces. Ending the second war was accomplished through four incremental peace agreements: the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement (1999), the Sun City Agreement (April 2002), the Pretoria Agreement (July 2002) and the Luanda Agreement (September 2002) that ultimately contributed to the Global and Inclusive Agreement of December 2002 which finally ended the war. It is important to note that these different peace agreements did not succeed in stemming the violence in the DRC and this can be attributed to the fact that the conflict had many actors whose interests were not sufficiently addressed to compel them to agree to enter into any agreement(s) or respect the one(s) entered into. Even though these agreements did not effectively curb violence in many parts of the DRC, they served as instrumental pillars for the Global and Inclusive Agreement which ended the Second Congo War and which led to the formation of a unified Transitional Government of the DRC in 2003. This agreement has, however, not succeeded in ridding the DRC of violence, especially in the eastern regions, in what can be considered as the third episode of the conflict.5

The origins of the current conflict can be traced back to 2003, when the country was being unified after years of civil war, and all belligerents were obliged to integrate their troops into the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC). A group of officers from the Rwanda-backed RCD, however, refused to join the FARDC. They launched a rebellion which they called the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP). In January 2009, the CNDP was integrated into the FARDC after a peace deal. In April 2012, CNDP members in the FARDC mutinied and subsequently formed the March 23 (M23) rebel group. The mutiny was a pre-emptive move to prevent their leaders from being dispersed from eastern DRC to other parts of the country. The Rwandan government has been accused of supporting the M23.6

The three phases of the war in the DRC were also reportedly fuelled and supported by various national and multinational corporations (MNCs) which sought to obtain mining concessions or contracts in the country on terms that were more favourable than they would have received in countries where there was peace and stability. MNCs reportedly developed networks of key political, military and business elites to exploit the DRC’s natural resources.7 MNCs also traded with rebels who, upon taking control of mineral-rich areas, set up financial and administrative bodies so as to obtain revenue from the minerals. Revenue gained from trade in the DRC’s natural resources has assisted all the armed belligerents to fund their participation in the conflict, as well as to enrich themselves.

Why has peace been elusive in the DRC?

There has been significant international attention and continental commitment through the AU and sub-regional commitment through the ICGLR to stem the violence in the DRC. The UN has deployed its most expensive peacekeeping mission to the DRC. Its mandate has over the years been revised to increase the capacity of this force to protect civilians. Other efforts have been made by various actors to build peace in the DRC. Civil society groups continue to work at grassroots level to transform the roots and culture of violence, but vicious cycles of brutality remain worryingly high. This situation necessitates an examination of why peace continues to remain elusive. There are various reasons which explain why the DRC has failed to consolidate peace, despite the different peace processes and efforts made to secure sustainable amity.

Complexity of the conflict as a result of the involvement of neighbouring countries

Almost all stages of the DRC peace process have been characterised by the involvement of external actors who have played critical roles which have at times been helpful and at times destructive. Many countries and militant groups were directly involved in the conflicts in the DRC. Most, if not all, of these parties had strong preferences regarding the outcome of the transitional arrangements.8 This is because all these countries were motivated to be part of the war by particular interests, which necessitated their follow-up to ensure that the ensuing peace accords reflected these. These interests were mainly based on the need to ensure that the DRC did not continue to serve as rear bases for rebel groups that operated against mainly Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Angola. With the many parties and diverse interests involved, negotiating a representative settlement became challenging. The Second Congo War, for example, saw the participation of up to nine countries.9 Although the war officially ended with the formation of the transitional government in mid-2003, since then Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda, which all participated in the Second Congo War, have made incursions into eastern DRC. These invasions have mainly been driven by national security interests, but ultimately they have served to contribute to the instability of the DRC.

Uganda’s military presence in the DRC

The Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) has been engaged in attempts to rid northern Uganda of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group accused of widespread human rights violations, including murder, abduction, mutilation, child sex slavery and forcing children to participate in armed hostilities. When confronted by the formidable forces of the UPDF, the LRA often retreats to, among other countries, the DRC. This situation has provided opportunities for the UPDF to invade the eastern DRC in pursuit of the rebels. There have also been instances when the FARDC and UPDF have collaborated on joint operations to capture or kill LRA commanders and their followers.10 In spite of these operations, a small residual UPDF element still remains in the DRC to support anti-LRA operations by the FARDC. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) are another rebel group that the UPDF has been in constant pursuit of inside the DRC. The ADF is a combination of fundamentalist Tabliq Muslim rebels and residual forces of another rebel group, the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda. The ADF is suspected of being responsible for dozens of bombings in public areas in Uganda and uses kidnapping and the murder of civilians to create fear in the local population and to undermine confidence in the government. Operating from north-eastern Congo, the ADF has in the past received funding, supplies and training from the Government of Sudan, as well as from sympathetic Hutu groups.11 While in pursuit of rebel groups in the DRC, the UPDF has been accused of committing atrocities such as massacres of civilians, torture and destruction of critical civilian infrastructure. As they countered the UPDF offensive, the ADF and the LRA have also reportedly subjected Congolese civilians to human rights violations.12

Rwanda’s involvement complicates the conflict

Rwanda’s involvement in the DRC is more intricate than that of the other actors. The Rwandan army has been battling the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a political-military movement which is active in the North and South Kivu provinces of the DRC. The movement consists of ex-Rwandan Armed Forces, ex-Interahamwe militia,13 Hutu civilians who fled to eastern DRC after the 1994 genocide and other young Hutu directly recruited from Rwanda. Hutu civilians make up the majority of the FDLR. The FDLR has carried out many attacks inside Rwanda and against Congolese civilians.14 It is still determined to return to power in Rwanda, but claims that it prefers political dialogue with the Rwandan government to going to war. The presence of the FDLR in North and South Kivu is problematic as it gives Rwanda a reason to continuously intervene in the DRC.15 Rwanda initially tackled the FDLR threat in December 2006 by setting up and supporting the CNDP, which went on the offensive against FDLR, in the process triggering humanitarian crises and civilian deaths in eastern DRC. Although, following a pact with the DRC government, the CNDP became a political party in March 2009 and its fighters were integrated into the FARDC, former CNDP members in the FARDC mutinied in April 2012.16

Rwanda’s alleged support for the M23 could be a continuation of its cooperation with ex-CNDP members, to ensure that the FDLR does not reorganise itself in the DRC. The M23’s main claims revolve around the lack of political will on the part of the DRC government to fully implement the 2009 Goma Agreement signed between the government and the CNDP. The movement has been vocal in calling for direct talks with the government in order to address questions relating to its political and military integration. The M23 poses a serious renewed threat to the humanitarian situation, as well as to the peace and security of the entire region.17

The involvement of Burundi

Although its role has been less prominent than that of Rwanda, the Burundian army has also been crossing over into the DRC to pursue members of armed opposition groups, most notably the National Forces of Liberation (FNL). The FNL is a Burundian political party originally formed in 1985 as the military wing of a Hutu-led rebel group called the Party for the Liberation of the Hutu People (PALIPEHUTU). In the early years following the group’s formation, its demands centred on the establishment of a government and army in Burundi that was representative of the ethnic balance in the largely Hutu country, rather than just empowering the Tutsi minority.18 After signing a peace deal with the Government of Burundi in September 2006 the PALIPEHUTU-FNL became FNL. The change in name was necessitated by the need to adhere to a law governing political parties in Burundi that prohibits the use of party names that bear references to ethnicity, religion or any sectarian identities. In as much as there was the integration of FNL fighters into Burundi’s national army before and after the 2010 elections, the remnants continued with their rebellion. They later began infiltrating the Ruzizi plains and Lake Tanganyika, often crossing into the South Kivu province where they created rear bases from which to fight Burundi’s armed forces. The FNL currently appears to be in an alliance with the FDLR in South Kivu.19 The eastern DRC provides a stronghold for the FNL and other rebel movements to orchestrate attacks inside Burundi.20 The continued existence of the FNL in the DRC has provided a strong rationale for the Burundian army to conduct counter-insurgency measures in the DRC. The effects of such measures have been devastating to the local populations.21

The lure of natural resources and motivations of international third parties

Throughout recent history, business entities have had a keen interest in the DRC. That interest is due to geo-strategic reasons and the fact that the country is laden with important minerals that are critical to the work of a range of industries. The irony is that whereas these entities benefit a great deal from the mineral wealth of the DRC, they do not seem to extend any importance to the socio-political issues that are a consequence of their activities. Montague posits that several mining companies domiciled in western nations fund military operations in exchange for lucrative contracts in the east of the DRC.22 The presence of unregulated mining operations in the DRC is one of the biggest impediments to peace in the country. For as long as these mining companies operate in the prevailing conflict-laden environment that allows them to trade arms for minerals, peace in the DRC will remain a pipe dream.

Foreign policies of states exist to serve their national interests, including economic interests. The availability of strategic minerals in a country continuously shapes the foreign policies of other nations towards the country. The commercial interests in the DRC are therefore intrinsically linked to the national interests of the countries where the investments originate from.23 This contributed to the involvement of many countries in the first and second Congo wars. The fact that there were, and continue to be, so many actors is perhaps one of the biggest challenges to the achievement of sustainable peace in the DRC. The conflict in the DRC has many national and international actors. These actors include Congolese nationals, traders from neighbouring countries, MNCs and western nations, among others who benefit from the mineral trade. Some are visible and some use proxies to further their interests. The actors who have used proxies have not had their interests tabled for settlement or negotiation. The situation is compounded when some of these actors and their proxies offer to facilitate the mediation of the conflict. The complexity is due to the fact that business interests that fuelled and continue to fuel the conflict originate from the same western nations and are supported by countries surrounding the DRC.24 This results in conflict of interest with regard to their (western nations and neighbouring countries) role in any attempts aimed at resolving the conflict in the country. The situation that has prevailed is that the interests of some members of the international community, most notably western nations and African countries that exploit the DRC minerals, have never been openly addressed and so they always remain spoilers.

Challenges of state consolidation

The territory of the DRC is about a fourth of the size of the United States (US), or about the size of Western Europe. The sophisticated web of external interventions and insurgencies after the Second Congo War has rendered the DRC essentially ungovernable. Throughout its entire history since independence, the central government has never succeeded in establishing political order backed by the rule of law.25 The first and second Congo wars created a political vacuum in many parts of the DRC, most notably in the east. Vast sections of the country remain politically and logistically disconnected from the seat of government – Kinshasa. This situation has made a significant portion of the population feel disenfranchised and marginalised.26 With a ready supply of arms from dubious mineral trading entities and external actors with questionable interests, disaffected groups have been quick to carve their destinies parallel to those of the DRC state. This has created a situation in the DRC where mineral-rich areas are typically infested with militias.27 Because the DRC’s provinces are politically, socially and economically disconnected from each other, the sense of a unified national identity and patriotism is weak, which creates a vacuum that has been filled by militias, rebellions and unwelcome foreign interests.

Delayed justice for victims of violent conflicts and inadequate reconciliation in the DRC

An important transformative aspect of the Global and Inclusive Agreement was its provision for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). After reaching the Agreement and implementing it, actors in the conflict needed to consultatively create a new development order focusing on, among other things, education, rebuilding homes, creating jobs and enhancing livelihoods, establishing an enlightened government, conducting disarmament and dealing with the question of refugees and internally displaced persons. More importantly, the actors needed to face up to the past, share their grief and reconcile their differences. This process requires sensitivity, courage and, above all, immense patience. It is the absence or inadequacy of the aforementioned reconciliation process that poses another major risk to the DRC peace process. The TRC, which would have enhanced the transformative process, was mired in controversy. Formed in July 2003, the TRC was operational for three years and 10 months. The selection of the commissioners, while inclusive and representative of the political forces involved in the peace negotiations, was criticised because some of the commissioners had informal ties with those who were implicated in the crimes. It is no wonder that the TRC failed to investigate atrocities or hold public hearings to establish the truth about the conflict and mass killings.28 Since 1996, as many as 500,000 people, particularly women and girls, have been victims of rape and sexual violence.29 Hundreds of thousands of others were displaced and consequently lost property and livelihoods. Most of the perpetrators of these crimes have not been brought to justice due to under-funding, inability to reach remote areas and questions over the integrity of judicial officials. The victims and their communities have felt these shortcomings to be injustices. For a society to transition into peace, it is important that injustices that were committed before and during the conflict are addressed.30

Inadequate local ownership of peacebuilding interventions by civil society organisations

It has been suggested that since the causes of the DRC conflict were also distinctively local, they could only be properly addressed by combining action at grassroots level with intervention at higher political levels.31 Most of the grassroots conflicts required a considerable measure of bottom-up approaches to peacebuilding, in addition to the top-bottom approaches. However, it has been noted that only a few non-governmental organisations conducted bottom-up peacebuilding in the most fragile flashpoints. There was no attempt to resolve land disputes, to reconstruct grassroots institutions for the peaceful resolution of conflict, or to promote reconciliation within divided villages or communities, even though international and Congolese actors could easily have done so, or supported these initiatives, with the resources at hand.32

Recommendations

The DRC has been plagued with latent conflicts which have led to eruptions of vicious cycles of violence over the years. This Policy & Practice Brief suggests that to effectively address the question of sustainable peace in the DRC it is important that the recommendations below be taken into consideration.

The Congolese government must adopt pro-transformative approaches to governance:

- Citizens of the DRC will begin to nurture a change in mindset if they feel that the government exists to better their lives and that the political processes in the DRC are not absolutely zero-sum in nature. The continued violence in eastern DRC could indicate, among other things, that the spirit of the peace process has not resonated with communities. The government must take stock of the peace process and come up with a blueprint that addresses electoral reforms, equitable development, improved standards of living, enhancement of national security and territorial integrity. Most importantly, the blueprint must give priority to the promotion of national healing and reconciliation. It must redefine relationships in the DRC by offering alternatives to violence as a means of resolving conflicts between political groups.

Belligerents and emerging political actors in the current crisis should find better ways to dialogue:

- A good example of an effective and practical dialogue process is the Inter-Congolese Dialogue of 2001 which brought together the various actors in the conflict to chart a way forward for the DRC. A similar or better framework could be adopted for use in the current crisis. When political groupings and citizens feel that they have an avenue through which to periodically reflect on their relationships and actions, a transformative process is enhanced in that mutual suspicions are not allowed to become deep-rooted to the point of violence. An example from the African continent is the establishment of District Peace Committees (DPCs) in Kenya in the 1990s. DPCs contributed substantially to pacification and redefinition of relationships between pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in the country’s North-Eastern Province, to the extent that they were insulated from negative ethnicisation and eventual violence in the period shortly before, during and after the 2007 general elections.33

The AU should closely monitor the current crisis:

- The DRC needs a comprehensive roadmap to resolve the current crisis and enhance the conflict transformation process. Just as the AU was instrumental in ending the Second Congo War and supporting the establishment of a recognised government in Kinshasa, the institution can continue to play an important role by providing resource persons with ‘good offices’ that can assist the government and the people of the DRC to consultatively develop and implement this roadmap. The underlying conflict issues stem from before the First Congo War and given their complexity and evident ability to spark unrest in recent times, the AU should rise to the task of assisting DRC citizens in their quest for conflict transformation. Given its size, wealth and location, the DRC is of immense geo-strategic significance to members of the AU. A stable DRC would provide African states with a viable economic and political partner with which to conduct diplomacy on relatively equitable terms. The AU should therefore not leave the DRC to drown in vicious cycles of intractable conflicts. As an urgent course of action, the African Standby Force (ASF) must also be operationalised and prepared for any eventualities in the DRC and other African hotspots. The ASF can provide a viable option (to the existing ones) to tackle peacebuilding and conflict management challenges in Africa.

The UN should take measures against entities that facilitate the illicit exploitation of the DRC’s natural resources:

- The presence of natural resources has been linked to serious problems, including armed conflict, in the DRC. The issues of illegal mining and exploitation of natural resources must be tackled in a sustainable way. The interim report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo34 has made several recommendations. These recommendations need to be translated into action by the UN Security Council (UNSC) which is globally mandated as the primary enforcer of peace and security. Considering that the illegal plunder of the wealth of the DRC clearly threatens international peace and security, the UNSC should rise above the interests of its individual members in the DRC and set deterrent measures to oblige countries whose companies or nationals engage in pillaging in the DRC to put in place legal frameworks to prevent the same. The US government recently put in place regulatory mechanisms to control the sourcing of minerals from the DRC by public companies that originate from the US.35 This illustrates how countries can control the activities of their companies outside their borders.

A strong, coordinated and robust civil society is a critical ingredient for conflict transformation:

- International non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and development agencies should strengthen civil society organisations (CSOs) in the DRC to enable them to effectively work with grassroots communities for purposes of peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Experiences and lessons from South Sudan have shown that strengthened and coordinated CSOs can be instrumental in the provision of social amenities in the absence of a strong government. During the 21 years of civil war in South Sudan which ended with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, it was CSOs that provided basic amenities like education, water and sanitation, among other services, to the local population. This ensured that to some extent, communities made attempts to move from humanitarian crisis towards development, albeit in a situation of active conflict.36 Local CSOs in the DRC continue to remain institutionally weak and poorly coordinated, in spite of the presence of the UN and INGOs. If these CSOs remain weak, post-conflict peacebuilding and conflict transformation is unlikely to be effective.

Conclusion

The ongoing violent crisis in the DRC threatens to reverse gains made in the peace process and through the implementation of peacebuilding efforts. The current interest by regional and international actors in the crisis provides an opportunity for laying a framework for the resolution of the underlying structural issues that have plagued the DRC for a long time. The reality is that historical issues will take a long time to resolve and that the peacebuilding process in the DRC cannot be tied to a timeline. The actors and stakeholders interested in consolidating peace in the DRC must focus on transformative strategies that are aimed at ensuring the development of infrastructure for a stronger and more peaceful DRC. This will involve coalesced efforts and context-specific long-term peacebuilding strategies by multiple stakeholders whose interests are entrenched in reconciliation and wellbeing of the people of the DRC.

Endnotes

- The author wishes to thank his colleagues Dr Grace Maina and Daniel Forti for their invaluable comments, insights, reviews and critiques of this brief.

- Miller, C.E. 2005. A glossary of terms and concepts in peace and conflict studies. Addis Ababa, University for Peace.

- United Nations. Undated. Why the DRC matters. Available from: <http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/monuc/documents/drc.pdf> [Accessed 4 October 2012].

- Stearns, J.K. 2011. Dancing in the glory of monsters: The collapse of the Congo and the great war of Africa. New York, Public Affairs.

- Ibid.

- BBC News. 2012. Rwanda supporting DR Congo mutineers. BBC News Africa, 28 May. Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-18231128> [Accessed 18 July 2012].

- Shah, A. 2010.The Democratic Republic of Congo. Available from:

<http://www.globalissues.org/article/87/the-democratic-republic-of-congo#AnInternationalBattleOverResources> [Accessed 4 October 2012]. - Curtis, D. 2007. Transitional governance in Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In: Guttieri, K. and Piombo, J. eds. Interim governments: Institutional bridges to peace and democracy? Washington D.C., USIP Press Publications. pp. 171–194.

- Davidsson, P. and Thoroddsen, F. 2011. Rule of law programming in the DRC for the sake of justice and security. In: Sriram, C.L., Martin-Ortega, O. and Herman, J. eds. Peacebuilding and rule of law in Africa: just peace? New York, Routledge, pp. 111–126.

- International Business Publications. 2009. Congo Democratic Republic mineral and mining industry, investment and business guide: Strategic information and basic laws. Washington D.C., International Business Publications.

- Global Security. 2011. Allied Democratic Forces. Available from: <http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/adf.htm> [Accessed 2 October 2012].

- United Nations Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 2010. Report of the mapping exercise documenting the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed within the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between March 1993 and June 2003. Available from: <http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/ZR/DRC_MAPPING_REPORT_FINAL_EN.pdf> [Accessed 17 July 2012].

- The Interahamwe militia was formed by groups of young people of the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRNDD) party in Rwanda. They carried out acts of genocide against Tutsi in 1994. Following the invasion of the Rwandan capital, Kigali, by the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), many Rwandan civilians and members of the Interahamwe fled to neighbouring countries, most notably to the DRC.

- Dagne, T. 2008. Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and current developments. Washington D.C., Diane Publishing.

- Reynaert, J. 2011. MONUC/MONUSCO and civilian protection in the Kivus. Available from: <http://www.google.co.za/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CCEQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ipisresearch.be%2Fdownload.php%3Fid%3D327&ei=f-ipUJmxDIKFhQewkoGQCw&usg=AFQjCNEeEvZ0EFycR70GBTJUwH0IEdJtZQ> [Accessed 19 November 2012].

- International Crisis Group. 2012. Eastern Congo: why stabilisation failed. Available from: <http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/central-africa/dr-congo/b091-eastern-congo-why-stabilisation-failed> [Accessed 19 November 2012].

- UN Security Council. 2012. Addendum to the interim report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (S/2012/348) concerning violations of the arms embargo and sanctions regime by the Government of Rwanda. Available from: <http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/393/39/PDF/N1239339.pdf?OpenElement> [Accessed 18 July 2012].

- Jane’s Information Group. 2012. Forces Nationales de Liberation (FNL). Available from: <http://articles.janes.com/articles/Janes-World-Insurgency-and-Terrorism/Forces-Nationales-de-Liberation-FNL-Burundi.html> [Accessed 19 November 2012].

- 2012. The foreign armed groups. Available from: <http://monusco.unmissions.org/Default.aspx?tabid=10727&language=en-US> [Accessed 8 August 2012].

- Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011. Available from: <http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/wr2012.pdf> [Accessed 8 August 2012].

- Ibid.

- Montague, D. 2002. Stolen goods: Coltan and conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. SAIS Review, XXII (1), pp. 103–118.

- Landsberg, C. 2003. The United States and Africa: Malign neglect. In: Malone, D. and Khong, Y.F. eds. Unilateralism and U.S. foreign policy. London, Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 347–374.

- Montague, D. op cit.

- Bratton, M. 2005. Building democracy in Africa’s weak states. Democracy at Large, 1 (3), pp. 12–15.

- Kibasomba, R. and Lombe, T.B. 2011. Obstacles to post-election peace in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Actors, interests and strategies. In: Baregu, M. ed. Understanding obstacles to peace: Actors, interests and strategies in Africa’s Great Lakes Region. Kampala, International Development Research Centre. pp. 61–145.

- Enough Project. 2012. Eastern Congo [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.enoughproject.org/conflicts/eastern_congo> [Accessed 9 November 2012].

- The International Center for Transitional Justice. 2012. The Democratic Republic of Congo. Available from: <http://ictj.org/our-work/regions-and-countries/democratic-republic-congo-drc> [Accessed 11 July 2012].

- Porter, L. 2012. Mobile gender courts: delivering justice in the DRC. Available from: <http://thinkafricapress.com/drc/tackling-impunity-democratic-republic-congo-rape-gender-court-open-society> [Accessed 3 October 2012].

- Maiese, M. 2003. Social structural change. Available from: <http://www.beyondintractability.org/bi-essay/social-structural-changes> [Accessed 3 October 2012].

- Autesserre, S. 2010. The trouble with the Congo: Local violence and the failure of international peacebuilding. New York, Cambridge University Press.

- Ibid.

- Adan, M. and Pkalya, R. 2006.The Concept Peace Committee: A snapshot analysis of the Concept Peace Committee in relation to peacebuilding initiatives in Kenya. Nairobi, Practical Action.

- UN Security Council. 2012. The interim report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (S/2012/348). Available from: <http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/348/79/PDF/N1234879.pdf?OpenElement> [Accessed 18 July 2012].

- S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2012. SEC adopts rule for disclosing use of conflict minerals. Available from: <http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2012/2012-163.htm> [Accessed 19 November 2012].

- Deng, L.K. 2003. Education in southern Sudan: War, status and challenges of achieving education for all goals. Available from: <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001467/146759e.pdf> [Accessed 19 July 2012].