- Policy & Practice Brief

The Twentieth Anniversary of UNSCR 1325

This Policy & Practice Brief forms part of ACCORD’s knowledge production work to inform peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding

Executive summary

The year 2020 marked two milestones for women’s rights and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda: the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, as well as the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325). Both of these international commitments stressed the importance of advancing women’s rights, particularly in relation to their participation efforts to achieve peace and security. However, the COVID-19 pandemic derailed existing plans to mark these achievements. Instead of allowing the pandemic to further disrupt the strides that have been made to advance women’s human rights over the last two decades, it is critical that peace and security activists reframe the circumstances created by the pandemic as an opportunity to secure meaningful change. Within this context, this Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) will critique the progress made in the WPS’ agenda since the adoption of UNSCR 1325 and provide African perspectives on what should be prioritised over the next 20 years.

Introduction

The year 2020 heralded a unique opportunity to celebrate the global achievements made by women’s rights activists and proponents in the WPS field. The United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU), national governments, and civil society organisations (CSOs) had all planned events to celebrate the accomplishments and, in some instances, shortcomings, of the UNSCR 1325. However, these plans, like many others, were derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic as quarantines and social distancing measures changed the possibilities of our ‘normal’ interactions throughout the world. It is critical that we now find alternative ways of reflecting on the WPS agenda to ensure that this vital opportunity is not lost. Indeed, COVID-19 has demonstrated just how relevant the WPS agenda is – given that issues of human security, and specifically women’s rights, have increasingly come under threat as a result of the pandemic.

It is within this context that this PPB will identify gains made in the WPS agenda over the last two decades, as well as ongoing challenges that persist despite global commitments. This will be done by focusing on a few critical themes that underpin the UNSCR 1325 agenda:

- women’s participation in peace processes;

- protection from and prevention of violence, especially conflict-related sexual violence;

- referencing of gender provisions in peace agreements; and

- allocation of funding to the WPS agenda.

Background on WPS

African women have always played active roles in mediating and negotiating peace, and many historians have documented women’s importance in resolving conflict in pre-colonial African societies.1 However, Nigerian scholar Ifi Amadiume has noted that Eurocentric and patriarchal interpretations of Africa’s past concealed the importance of matriarchy and women’s leadership in many pre-colonial African societies.2 As she and others have revealed, the colonial period remade (or made) gendered systems of power and authority on the continent and, in turn, restricted the powers that pre-colonial women enjoyed by deepening patriarchal domination. Indeed, colonialism was accompanied by new understandings of gender roles that became entrenched with the introduction of colonial economies. As a result of this process, men became conceptualised as people linked with categories such as politics, economics, or race, while women became reduced to gendered beings bound by their relationships to men as wives, widows, mothers or daughters.3 Helen Bradford reveals that omitting women’s experiences in these interpretations of Africa’s past became ‘part of the politics of the gender system’.4

This marginalisation of women’s roles continued to persist in post-colonial societies despite African women’s visibility in the independence struggles that swept across the continent in the second half of the twentieth century. From Ghana to Zimbabwe, women demanded, and were promised, their participation and recognition in all aspects of the post-colonial polity.5 Yet these promises failed to fully materialise, and the majority of African women continued to be excluded from full participation in the public realm for much of the twentieth century.

However, as Aili Tripp and others have suggested, awareness over the connections between women’s rights and conflicts manifested following the end of the cold war.6 As a result, during the 1990s women’s mobilisation across sub-Saharan Africa increasingly extended beyond the domestic to engage with the continental and international sphere. The UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing, China, in 1995, was the first time that the necessity for women’s participation in peace processes was formally recognised. The conference culminated in the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action which notably, drew specific attention to the issue of women and armed conflicts, stating that: ‘while entire communities suffer consequences of armed conflict and terrorism, women and girls are particularly affected because of their status in society and their sex.’7 As a result, the Platform presented recommendations for women’s increased involvement in conflict resolution, peace research, and strategies to mitigate violence against women.8

Women’s activism around peace and security can thus in part be explained by the growing acknowledgment that conflict affects women and girls in unique ways. The use of sexual violence as a weapon of war has been a common feature of conflict in contexts as diverse as Rwanda, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). But as studies have shown, conflict also disrupts existing gender roles – allowing women and girls to enter the public sphere and be valuable participants in local activism to mediate peace.9 For example, Marie Berry has noted how, bolstered by the support for women’s rights following the Beijing Platform for Action, by 1997 over 15 400 new women’s organisations had been created in Rwanda.10

Nonetheless, prior to 2000, African women’s involvement in peace and security efforts were largely unrecognised by the international community and occurred in predominantly informal capacities. Ultimately the UNSCR 1325 was adopted in October 2000, and it is now regarded as the formative document for the WPS agenda as well as a critical tool to build a more equal and peaceful world.11 To date there have been nine additional resolutions on WPS including: 1820 (2009), 1888 (2009), 1889 (2010), 1960 (2011), 2106 (2013), 2122 (2013), 2242 (2015), 2467 (2019), and 2493 (2019).12 The core commitments of the WPS agenda are enshrined in four pillars; prevention, (2) participation, (3) protection, and (4) relief and recovery.13 Buttressing these four pillars is the understanding that women’s participation is essential to post-conflict reconstruction, and this requires women’s involvement in decision-making over critical areas such as security, economic recovery, governance, and post-conflict justice.

Through its acknowledgment of the links between gender and conflict, the WPS agenda ideally ‘seeks both the radical reconfiguration of the gendered power dynamics that characterise our world and to propel global commitments to sustainable and positive peace.’14 Over the past 20 years, concerted efforts have been made to realise these four pillars through addressing conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence, increasing women’s participation in peace processes, attempting to protect women and girls from the atrocities of armed conflict and mainstreaming gender in peacebuilding initiatives. Yet, the impact of the WPS agenda has been inconsistent and uneven, in part because of its different interpretations based on context and expectations. Thus, despite UNSCR 1325’s important legal framework, rape as a weapon of war persists; women remain under-represented in peace processes and failures in the implementation of humanitarian law continue. Indeed, the UN Secretary General’s 2019 Report on Women and Peace and Security revealed that in situations on the agenda of the Security Council, 50 parties to conflict are credibly suspected of having committed or instigated patterns of rape and other forms of sexual violence and 20% of refugee or displaced women experience sexual violence.15 This begs the question: what can be done better?

Twentieth Anniversary of Resolution 1325: Why Should We Care?

Since the adoption of UNSCR 1325, the dynamics of conflict have evolved, and research suggests that conflict will continue to change as environmental degradation intensifies due to climate change. Over the last two decades, new war theory has revealed that globalisation, the increase in weak or failing states, the growth in electoral-related violence as well as the development of new technology, has resulted in conflict primarily occurring within states rather than between states.16 This ever-increasing complexity of conflict has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic – evident in the growth of localised hostilities, as well as widespread reports of lockdown-related violence by security forces against civilians. The pandemic has also been paralleled by a shadow pandemic with increased levels of domestic and sexual violence reported across the globe. Nonetheless, the shifts in the scope and nature of conflict has also resulted in a concomitant change in responses to conflict by policymakers with an increasing recognition of the need for human security.

Therefore, in the context of the 20th anniversary of UNSCR 1325 in October 2020, it is important to both reflect on achievements made thus far, but also to evaluate what challenges remain. Not only is the goal of increasing women’s meaningful representation and participation in peace processes a goal in and of itself; it can potentially create a more inclusive, equal and peaceful world. Analyses of peace agreements over the last two decades have revealed that women’s inclusion in negotiations increases the chances of the agreement being more inclusive and considerate of the needs of other marginalised groups.17 In O’Reilly et al.’s analysis of 40 peace processes, it is suggested that those that include women as witnesses, mediators, or negotiators were 20% more likely to last at least two years. They also contend that there is a 35% increase in the probability of a peace agreement lasting 15 years when women are involved.18 In addition, by having women participate in negotiations, it increases the chances of a higher rate of implementation, since women have proven active in ensuring that agreements are implemented.19 It has also been shown that transitions from conflict often allow for women’s increased political participation and, in turn, gender-sensitive legal change.20 Both South Africa and Rwanda are examples of how the inclusion of larger numbers of women in the legislature corresponds with higher rates of women’s rights reforms.21

Moreover, as governments work to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outlined in the UN’s Agenda 2030, promoting the objectives of WPS is central to SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Institutions), as well as SDG 17 (Partnerships to Achieve the Goals). At the same time, African countries are working towards the goals set forth in the African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063 among which Aspiration Six notes the central role of African women for the continent’s development. In order to promote the WPS agenda the AU has made important strides through, for instance, the creation of an AU Special Envoy on Women Peace and Security in 2014 and, more recently, the Peace and Security Council has adopted the Continental Results Framework (CRF) on Women, Peace and Security in Africa (2018– 2028). Equally significant is the AU’s support for the creation of the Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation (FemWise-Africa).

Assessing the Progress since the Adoption of UNSCR 1325

Assessing the achievements made in the field of WPS is a complex task. The field is broad and often international emphasis is placed on quantitative advancements such as the number of women involved in peace processes rather than qualitative changes to the security of women. Moreover, assessing what progress has been made is complicated by the fact that advances at the policy level may not always translate into meaningful change on the ground. This is further complicated by the fact that accurate data is often unavailable in many conflict situations. Nonetheless, this section will try to evaluate the progress made on some of the key concerns of the WPS agenda through consideration of: i) participation, ii) prevention and protection, iii) gender provisions in peace agreements, and iv) allocation of funding to the WPS agenda.

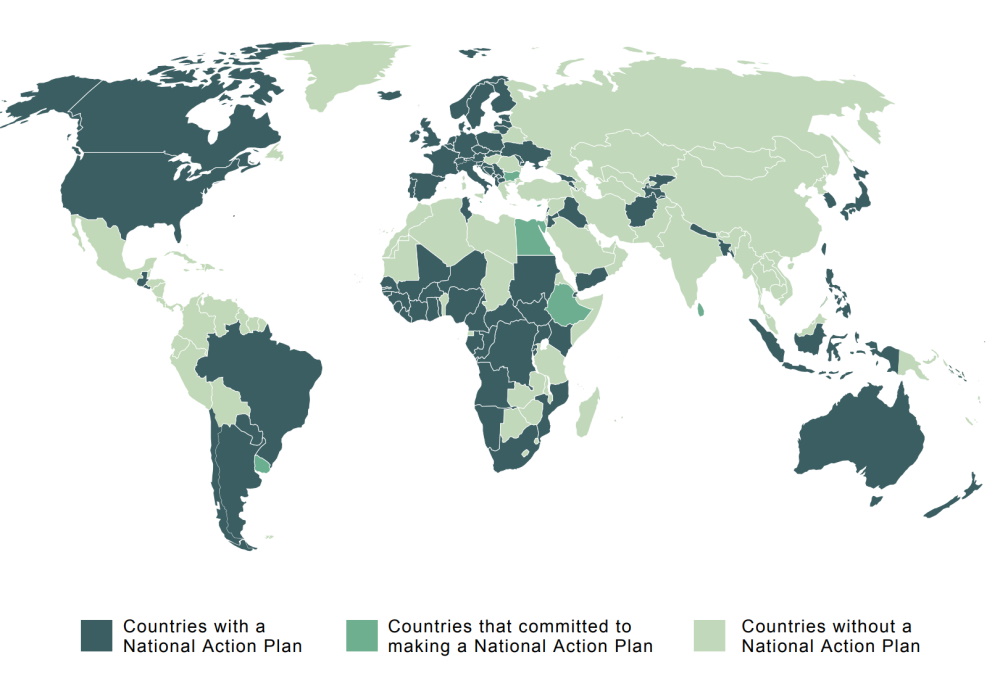

Since the adoption of UNSCR 1325, many national governments have created National Action Plans (NAPs) to ensure domestic commitments to the goals of the WPS agenda. According to the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) as of September 2020, 86 UN Member States had adopted NAPs (see Infographic 2). Moreover, 30 African countries have adopted NAPs, making Africa the continent with the highest percentage of NAPs.22 To date, Slovakia, Cyprus, Latvia, South Africa, Djibouti, Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Sudan are the latest countries to adopt NAPs in 2020.23

Innovatively, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) developed a Regional Action Plan (RAP) between 2011 and 2015 to act as a benchmark for countries when creating their own NAPs. The RAP supported the aims of tackling violence against women and girls, increasing the number of women at the negotiating table and supporting gender-inclusive peace processes. Following IGAD’s lead, other Regional Economic Communities have also devised RAPs – including the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC), and most recently in 2018, Southern African Development Community (SADC), making Africa the leader in regional approaches to WPS worldwide.24 As the world mobilises to curb the spread of COVID-19, 2020 has offered a significant opportunity to evaluate these African achievements, as well as ongoing challenges to achieving the WPS agenda, given the many cracks to its fulfilment revealed by the pandemic.

Infographic 1: UN Security Council Resolution: 2008 –201925

UN SECURITY COUNCIL WPS-RELATED RESOLUTIONS: 2008-2019

| SEPTEMBER 2009 RES. 1888 |

Reiterates that sexual violence exacerbates armed conflict and impedes international peace and security. Calls for leadership to address conflict-related sexual violence. |

| DECEMBER 2010 RES. 1960 |

Reiterates the call for an end to sexual violence in armed conflict. Sets up “naming and shaming” listing mechanism, sending a direct political message that there are consequences for sexualviolence. |

| OCTOBER 2013 RES. 2122 |

Explicitly affirms an “integrated approach” to sustainable peace. Sets out concrete methods for combating women’s participation deficit. |

| APRIL 2019 RES. 2467 |

Recognizes that sexual violence in conflict occurs on a continuum of violence against women and girls. Recognizes national ownership and responsibility in addressing root causes of sexual violence, and names structural gender inequality and discrimination as a root cause. |

| JUNE 2008 RES. 1820 |

Recognises sexual violence as a weapon and tactic of war. Notes that rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute a war crime, crime against humanity, or a constitutive act with respect to genocide. |

| OCTOBER 2009 RES. 1889 |

Focuses on post-conflict peacebuilding and on women’s participation in all stages of peace processes. Calls for the development of indicators to measure the implementation of UNSCR1325 (2000). |

| JUNE 2013 RES. 2106 |

Focuses on operationalising current obligations rather than on creating new structures/initiatives. Includes language on women’s participation in combating sexual violence. |

| OCTOBER 2015 RES. 2242 |

Encourages assessment of strategies and resources in regard to the implementation of the WPS Agenda. Highlights the importance of collaboration with civil society. |

| OCTOBER 2019 RES. 2493 |

Urges member states to commit to implementing the nine previously adopted resolutions; Urges Member States to commit to implementing the WPS agenda and its priorities by ensuring and promoting the full, equal and meaningful participation of women in all stages of peace processes |

Infographic 2 : Countries with National Action Plans for the Implementation of UNSCR 1325 26

Participation

As noted above, increasing women’s participation at the decision-making level in conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping and peacebuilding is central to the WPS agenda. However even the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, himself has noted that increasing women’s participation has garnered mixed results since UNSCR 1325’s adoption. In fact, his 2017 report on Women and Peace and Security identifies declines in the participation of women in peace processes, a decrease in the use of gender technical advisors and a drop in the inclusion of gender provisions in peace agreements.27 Thus, while there was some initial improvements in this area post 2000, for example, in the number of women in senior positions during peace processes, it appears these have not been sustained. This number reached 75% in 2015, compared to just 36% in 2011.28

Indeed, Antonio Guterres has cautioned that ensuring the meaningful participation of women in peace processes ‘remains a challenge’ and has become ‘increasingly difficult’ due to the progressively complex nature of conflicts.29 He indicates that, while the UN has committed to ensuring all mediation teams include women, the participation of women has not significantly improved. UN Women also paints a bleak picture revealing that between 1992 and 2018 women constituted a mere 3% of mediators, 13% of negotiators, and 4% of signatories in all major peace processes.30

More specifically, African women’s experiences in national and regional peace processes have been inconsistent. In 2016, the AU Commission’s review on the Implementation of the WPS Agenda in Africa, illustrated the low levels of women’s participation (see Infographic 3).31 For example, during the DRC peace process in 2003, women made up only 5% of the signatories. The same representation was also found in the 2008 peace process for North Kivu, DRC. More recently, women from Libya, Central African Republic, Sudan and South Sudan have faced numerous obstacles, as well as outright resistance, to demands for their participation in peace processes. For example, in South Sudan provisions to ensure a 35% quota for women in all pre-transitional and transitional government structure has only been realised in one committee to date.32

Infographic 3 : Women’s Participation in African Peace Processes33

| Country | Women signatories | Women lead mediators | Women witnesses | Women in negotiating teams |

| Sierra Leone (1999) | 0% | 0% | 20% | 0% |

| Burundi (2000) – Arusha | 0% | 0% | – | 2% |

| Somalia (2002) – Eldoret | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Cote D’Ivoire (2003) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (2003) | 5% | 0% | 0% | 12% |

| Liberia (2003) – Accra | 0% | 0% | 17% | – |

| Sudan (2005) – Naivasha | 0% | 0% | 9% | – |

| Darfur (2006) – Abuja | 0% | 0% | 7% | 8% |

| DRC (2008) – Goma – North Kivu | 5% | 20% | 0% | – |

| DRC (2008) – Goma – South Kivu | 0% | 20% | 0% | – |

| Uganda (2008) | 0% | 0% | 20% | 9% |

| Kenya (2008) – Nairobi | 0% | 33% | 0% | 25% |

| Central African Republic (2008) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Zimbabwe (2008) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Somalia (2008) | 0% | 0% | 10% | – |

| Central African Republic (2011) | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

Furthermore, in the three cases where African women were present as lead mediators during peace negotiations, they remained the minority. In both the peace processes that happened in the DRC in 2008, women made up just 20% of the lead mediators. Similarly, in Kenya’s 2008 peace process, women made up one third of lead mediators.

And in thirteen other processes that occurred during the same time period, women did not hold any positions as lead mediators.34 Furthermore, in situations of formal peace processes sponsored by the African Union, when women have been present, they have most often been on mediation rather than negotiation teams. Consequently, women’s participation in peace processes typically continues to happen on the margins outside of formal negotiations.

A major critique of the WPS agenda is that women’s participation in formal peace processes has been largely symbolic as opposed to providing substantive representation of women. While strategies to increase women’s participation challenge women’s exclusion, this approach is underpinned by the assumption that women’s issues and concerns automatically become part of the political agenda through women’s participation. However, it has become abundantly clear that the representation of women in peace processes does not always correspond with women achieving the ability to exercise their rights. For example, a situational analysis of the 2017 South Sudan’s peace process by Monash University described women’s participation throughout the peace agreement process as ‘descriptive and relatively tokenistic’.35 Further, while UNSCR 1325 calls for expanding the role and contribution of women as military observers and civilian police within UN peacekeeping missions this has seen quite meagre change. According to Kirby and Shepherd, it took a decade for the percentage of female peacekeeping troops to rise by 1% and, since 2010, the number of women in police contributions has not increased.36

Beyond representation, it has been shown that consultations with women’s groups are also a critical aspect in ensuring women’s experiences and demands are heard. UN Women’s 2015 Preventing Conflict Transforming Justice Securing Peace: Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council resolution 1325 (Global Study) found that ‘88% of all peace processes with UN engagement in 2014 included regular consultations with women’s organizations’.37 This was a significant increase considering the number was only 50% in 2011. Aili Tripp has detailed the role of women’s organisations during the 2007–8 Kenyan post-electoral violence in both monitoring and trying to resolve the conflict. She argues that their relentless mobilisation was influential in the AU’s decision to appoint Graça Machel to the mediation team.38 However, the call to support measures that draw on such local women’s peace initiatives can be improved, and more must be done to harness the experience of bodies such as the Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation (FemWise-Africa). Indeed, Funmi Olonisakin has argued that the emphasis on Member States’ responsibility for the implementation of UNSCR 1325 has effectively marginalised women’s organisations.

The disappointing progress in women’s substantive participation locally, regionally and internationally is despite the ten resolutions on the matter of WPS accepted since 2000. Much criticism has centred on the over-emphasis on issues of sexual violence in the resolutions, instead of issues of prevention, protection and participation. For example, only three of the ten subsequent resolutions – UNSCR 1889, 2122 and 2493 – focus primarily on issues of participation.39

Prevention and Protection

Protecting women and girls from violent conflict, especially conflict-related sexual violence, is key to the WPS agenda. Indeed, UNSCR 1325 notes that parties to armed conflict must respect international law related to the protection of women and calls on them to take precautions to protect women and girls from gender-based violence. This is based on the reality that certain common factors have defined women’s experiences of conflict, including direct violations of their physical integrity, for example through sexual violence, reproductive violations and enforced pregnancy. Forced marriages, sexual slavery, and abduction have also been key features of conflict in contexts as diverse as the Central African Republic (CAR), DRC and South Sudan.40 As Jelke Boesten has noted, the use of sexual violence in conflict ‘is integral to the repertoire of violence in war and similar to torture, is symbolic humiliation of the male enemy, reaffirms military masculinities [and] destroys enemy culture’.41

As mentioned earlier, the majority of the WPS-related resolutions adopted since 2000 have focused primarily on the protection of women in armed conflict and specifically on the issue of sexual violence. UNSCR’s 1820, 1888, 1960, 2106 and 2467 all identify protecting women and girls from instances of sexual violence and exploitation during and after armed conflict as a priority. This has been critiqued by many analysts due to its simplistic attention to women’s victimhood – which fails to address women’s roles as active participants in conflict, for example as members of liberation movements or insurgencies. It also serves to reinforce binaries of men as perpetrators and women as victims which further invisibilises widespread violence against men and LGTBQI communities during conflict.

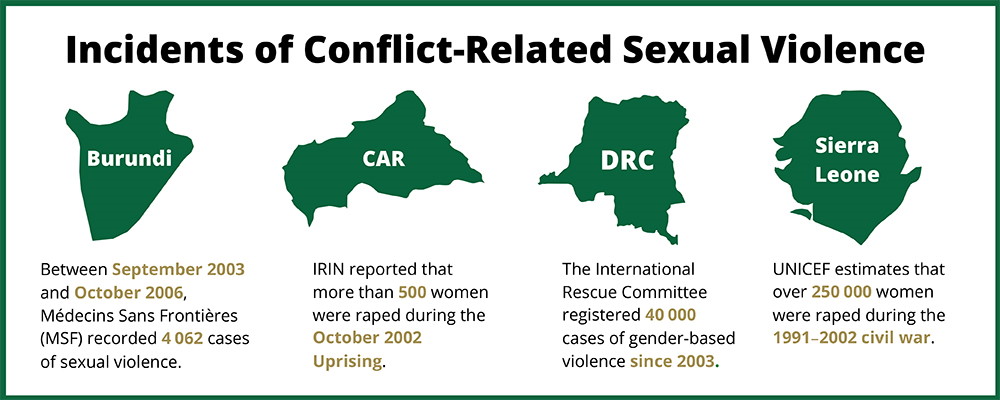

Moreover, despite these resolutions, high rates of conflict-related sexual violence continue unabated. The UN Secretary General detailed statistics published in May 2019 showed that: ‘unprecedented high levels of political violence targeting women’ including sexual violence, forced disappearances and physical assaults committed over the previous 12 months. This violence was perpetrated by both state and non-state armed groups.42 (see Infographic 4).

Infographic 4 : Incidents of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence43

The WPS agenda also stresses the responsibility of all States to prosecute those responsible for war crimes including those relating to sexual and other violence against women and girls, and there has been some progress in the prosecution of these crimes at the regional and international level. Significant developments in Africa include the jurisprudence developed at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL). The SCSL, for example, was seminal in categorising forced marriage as distinct from other forms of sexual violence, such as sexual slavery.

A further significant victory for women’s human rights on the continent was the 2016 conviction by the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) in Senegal of the former president of Chad, Hissene Habre, for crimes against humanity, including rape and sexual slavery. The EAC also ruled that 82 billion francs (CFA) be awarded in reparations to the victims of his crimes.44 At the national level, in a ground-breaking 2018 judgement a South Sudanese military court convicted ten soldiers for war crimes, including rape and sexual harassment and sentenced them to between seven to 14 years in prison.45

Nonetheless, various challenges continue to plague successful pursuit of accountability for gender-based violations during armed conflicts. These include the historic invisibility of crimes due to denial, societal acceptance of gender-based violence, and the silences created by stigma. Indeed, since the creation of the ICC, far from decreasing, incidents of violence against women in armed conflicts, continues unabated. In Africa, insurgencies, internal and/or cross-border conflicts, and mass displacement in Nigeria, Chad, the Central African Republic, Mozambique and South Sudan, to name but a few, have all been accompanied by widespread abuse of women. While the 2016 conviction of Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo was heralded for prosecuting rape as a war crime, however, in June 2018 he was acquitted by the ICC’s appeal chamber, which dealt a major blow to the prosecution of sexual violence in conflict.46

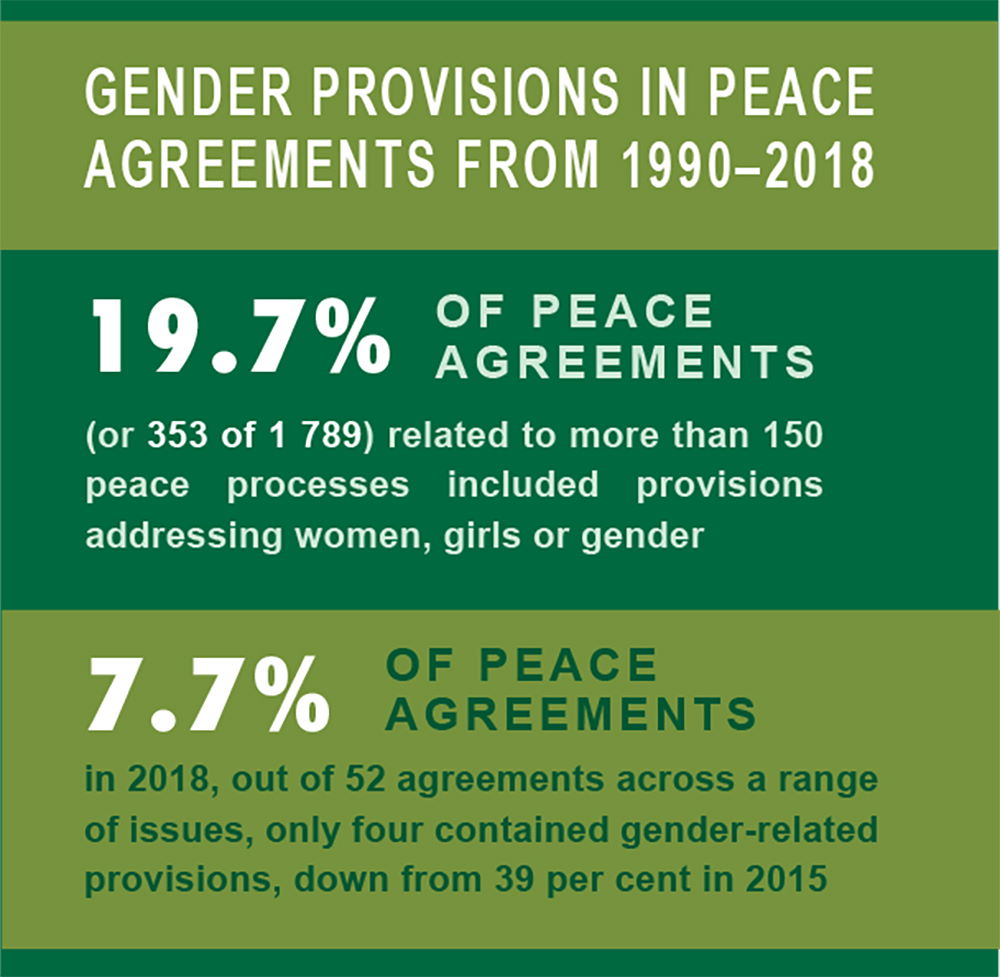

Gender Provisions Referenced in the Peace Agreements

UNSCR 1325’s calls for the inclusion of a gender perspective in peace agreements in relation to post-conflict reconstruction mechanisms as well as in the reform of constitutions, electoral systems and the judiciary.47 These measures might include gender quotas, provisions for political or legal equality or non-discrimination on grounds of gender or sex or social equality, property rights, or worker’s rights with reference to women. (see Infographic 5). As noted earlier, peace agreements are more likely to have gender provisions when women have participated in track one or two peace processes. This was revealed through analyses of 98 peace agreements that took place between 2000 and 2016 which showed for example how the 2014 CAR agreement made specific provisions for services and infrastructure to support women’s recovery from conflict.48 As Bell and O’Rourke have revealed, only 11% of peace agreements referenced women prior to the passage of UNSCR 1325 but this increased to, 27% after its adoption.49

Clearly some important advancements have been made following UNSCR 1325 regarding provisions in peace agreements. For example, ACCORD noted in 2011 that since the adoption of UNSCR 1325 there had been a significant increase in the number of women in politics in post-conflict settings, largely as a result of quota systems. Omotola Adeyoju Ilesanmi has further argued that the WPS agenda has created opportunities for African women through capacity building initiatives in peacebuilding afforded by organisations such as ACCORD, West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP) and Femmes Africa Solidarite (FAS).50 The importance of such initiatives was identified by Ekiyor and Wanykeki who noted that translating the conceptual language of UNSCR 1325 was critical for the resolution to be practically used as an advocacy tool.51

Yet, what has become evident is that not all mentions of women in peace agreements are positive, indeed some restrict rather than extend the participation of women. The Secretary General has shown, for example, that nearly 40% of economies continue to limit women’s property rights and nearly 30% restrict women’s freedom of movement.52 Furthermore, including a ‘gender perspective’ in peace agreements is also about much more than mentioning women, it affects a whole range of issues, including how civilian/combatant distinctions are addressed, how socio-economic rights are confronted or the type of electoral system are chosen.

Infographic 5: Gender Provisions in Peace Agreements53

Financing of the WPS Agenda

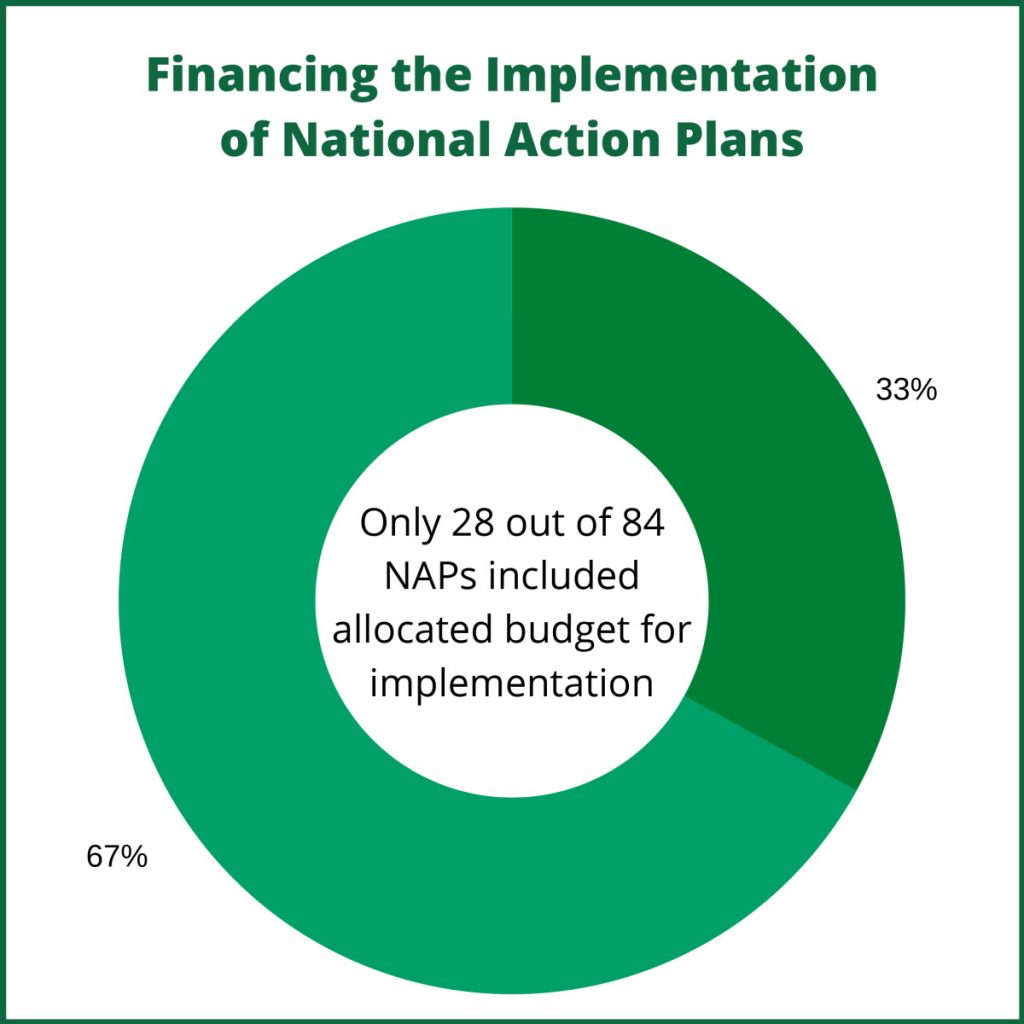

To understand any advancements made on the WPS agenda it is critical to examine the financial commitments being made by Member States. No matter how noble and essential the commitments, without dedicated funding it is impossible to achieve the objectives of UNSCR 1325. As noted above, progress on the development and implementation of NAPs have been made. However, adequate funding to implement these commitments are lacking and only 28 of the 84 NAPs adopted by December 2019 (33%) included a budget for the implementation at the time of adoption (see Infographic 6). Furthermore, while commitments have been made at the regional and international level, many governments rely on weak structures for the implementation of the WPS agenda given the inadequate resources allocated to these areas. It is also likely that the economic crisis that has been precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic will have ramifications in terms of budgetary cuts in gender-related programs.

Infographic 6: Financing the Implementation of National Action Plans54

Beyond the NAPs, only 24% of UN entities reporting data in 2015 had systems to track resources for gender equality and women’s empowerment.55 Further, the UN Women’s Global Study found that only a small percentage of ‘all aid to fragile states and economies addresses women’s specific needs.’ For example, in 2012 to 2013, ‘only 2% of aid to peace and security interventions in fragile states and economies […] targeted gender equality as a principal objective.’ Moreover, ‘OECD data show[ed] that in 2012–13, only USD 130 millions of aid went to women’s equality organsations and institutions – compared with the USD 31.8 billion of total aid to fragile states and economies over the same period.’ Thus, the study concluded that the lack of sufficient funds allocated to the WPS agenda has been one of the most persistent obstacles to the implementation of the agenda.

These findings by the Global Study appeared to have encouraged states to increase their funding towards the WPS agenda because, in 2015, UN Women reported that the ‘overall bilateral aid to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment in fragile and conflict-affected situations’ was rising. Nonetheless, it was recorded that in 2018, the total amount of money spent on the military was $1.8 trillion and annual military expenditures have increased globally by approximately 60% from 2000 to 2015. In addition, the majority of Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) programmes fail to include initiatives aimed at transforming violent masculinities. Thus, a huge disparity continues between spending allocated to the military compared to spending allocated to peace efforts, particularly in relation to the WPS agenda.

Conclusion: Assessing the Gaps in the WPS Agenda

Even a cursory look at the various objectives outlined in the WPS agenda shows that progress has been slow at best, sporadic at worst. The goal of women’s meaningful participation in peace and security thus remains far from within reach and greater effort is needed to ensure its realisation. While the adoption of UNSCR 1325 and its subsequent resolutions have been critical in responding to women’s exclusion over the last two decades much more needs to be done. Ultimately, the lack of progress is because nothing structurally or fundamentally has changed within global systems of power. Underlying patriarchal structures continue to allow the perpetuation of discrimination, inequality and marginalisation. Women will continue to be marginalised in all aspects of public and private life as long as the structures that perpetuate inequality continue to go unaddressed. As the WILPF has noted, five key obstacles continue to hinder the WPS agenda: Patriarchy, Inequality and Violent Masculinities; Militarisation; Social, Economic and Ecological Injustice; Fear, Polarisation and Fragmentation; and lack of effective implementation and accountability mechanisms all of which are relevant on the African continent.56

Yet, despite these obstacles, there has been indefatigable commitment to the ideals of the WPS agenda by women’s organisations across the continent. As outlined earlier, African women have always been integral in negotiating and building peace. Not even the COVID-19 pandemic could prevent women lobbying, advocating and working to have their demands heard. FemWise-Africa which has over four-hundred members of capable women ready to get to work building more peaceful communities is an example of capacity that could and should be utilised to implement the WPS agenda. Thus, going forward, attention must be given to how we can address and dismantle structures impeding the WPS agenda so that we can fully realise its goals, including sustainable development and peace on the continent.

Recommendations for the WPS Agenda

In order to increase women’s meaningful participation in peacebuilding, ACCORD has identified six areas we believe the WPS agenda should focus its efforts on over the next two decades.

- Recognise the shifting socio-economic and political environments created as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: These changing contexts will influence future conflict drivers and trends and this will have important implications for actors operating in the field of peace and security.

- Acknowledge women’s role at all levels during peace efforts: Women are currently active in various ways in early phases of peacebuilding but their role is often unrecognised. Ensuring acknowledgement, support and promotion of this work is critical to the WPS agenda;

- Better utilise the potential of Women Mediator Networks such as FemWise-Africa through networking opportunities and deployment at all track levels of peace processes;

- Appreciate the digitisation of the world as an opportunity: The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by the movement of people into the virtual space across the globe. While we acknowledge access to resources continues to create challenges, digitisation has awarded some important opportunities for greater inclusivity in the Global South including the development of new hybrid mediation methods and these should be maintained;

- Include men and boys more fully in WPS initiatives: Since men remain the gatekeepers of peace and security programmes it is important to work with them and ensure they are part of the solution to the WPS agenda; and

- Implement a transformative approach to WPS: Greater effort is needed to ensure that we move beyond the issue of representation to ensure qualitative change and a transformative effect for all women in post-conflict societies.

Endnotes

- Isike, C. and Okeke Uzodike, U. 2011. Towards an Indigenous Model of Conflict Resolution: Reinventing Women’s Roles as Traditional Peace-builders in Neo-Colonial Africa. African Journal on Conflict Resolution 11(2): 32–58. Available from: <https://www.academia.edu/39551369/Towards_An_Indigenous_Model_of_Conflict_Resolution_ Reinventing _Womens_ Roles_ as_Traditional_Peace-builders_in_Neo-Colonial_Africa> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- Amadiume, I. 1997. Re-inventing Africa: Matriarchy, Religion and Culture. Northampton, Interlink Publishing Group.

- Bradford, H. 1996. Women, Gender and Colonialism: Rethinking the History of the British Cape Colony and Its Frontier Zones, c. 1806–70. The Journal of African History, 37(3), pp. 351–370.

- Bradford, H. 1996. Women, Gender and Colonialism: Rethinking the History of the British Cape Colony and Its Frontier Zones, c. 1806–70. The Journal of African History, 37(3), pp. 369.

- Muvingi, I. 2016. Reclaiming Women’s Agency in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies: Women Use of Political Space in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa. In: Chedelin, S. and Mutisi, M. eds. Deconstructing Women, Peace and Security: A Critical Review of Approaches to Gender and Empowerment. Cape Town, HSRC Press, pp. 107–124.

- Tripp, A. 2015 Women and Power in Post-Conflict Africa Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- See Beijing Declaration and Platform, Fourth World Conference on Women (September 1995) Available from: <https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- McKay, S. and de la Rey, C. 2001. “Women’s Meanings of Peacebuilding in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” Peace and Conflict Journal of Peace Psychology 7(3): 227–242. doi: 10.1207/ S15327949PAC0703b_3.

- It is important to note, however, that there are cases where women have also taken up arms and been perpetrators of violence. Nonetheless, for the most part, it is men and boys who are most present as combatants.

- Berry, M. 2015. From Violence to Mobilization: Women, War and Threat in Rwanda. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 20(2), pp. 135.

- Ibid.

- For details of the resolutions Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2019. The Resolutions. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/resolutions> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- Ibid.

- Kirby, P. and Shepherd, L.J. 2016. The Futures Past of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda. International Affairs, 92(2), pp. 373–392. Available from: <https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/inta92-2-08-shepherdkirby.pdf> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- Guterres, A. 2019. Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280). Available from: <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Chigozie, Nnuriam Paul. 2018. The Application of New Wars Theory to African Conflicts Since 1960. International Journal of Arts and Humanities (6)6, pp. 313–320

- Mbwadzawo, M. and Ngwazi, N. 2013. “Mediating Peace in Africa: Enhancing the Role of Southern African Women in Mediation.” ACCORD 25: 1–10. <https://accord.org.za/publication/mediating-peace-in-africa/> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- O’Reilly, M., Súilleabháin, A. and Paffenholz, T. 2015. Reimagining Peacemaking: Women’s Roles in Peace Processes. New York; Geneva, International Peace Institute (IPI). Available from: <https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- Ibid.

- Krause, K., Krause, W., and Bränfors, P. 2018. “Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace.” International Interactions 44(6) 985-1016. doi: 10.1080/03050629.2018.1492386

- Ibid.

- According to data provided by the African Union’s Office of the Special Envoy on Women, Peace and Security.

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2020. National-Level Implementation. <http://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/implementation> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- Poulsen, K. 2019. Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa. (report no. 2018-6232). Available from: <https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjtuevlpefsAhXFmuAKHZhwBH4QFjAAegQIBhAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fum.dk%2F~%2Fmedia%2Fum%2Fenglish-site%2Fdocuments%2Fdanida%2Fabout-danida%2Fdanida%2520transparency%2Fdocuments%2Fu%252037%2F2019%2Fwomen%2520peace%2520and%2520security%2520agenda%2520in%2520africa.pdf%3Fla%3Den&usg=AOvVaw2638BKx5GhqpU7cg cl9J6H> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2019. The Resolutions. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/resolutions> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2020. National-Level Implementation. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/resolutions> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- ue, J. and Riveros-Morales, Y. 2018. Towards inclusive peace: Analysing gender-sensitive peace agreements 2000–2016. International Political Science Review, 40(1), pp. 23–40.

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2019. The Resolutions. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/resolutions> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- Guterres, A. 2019. Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280). Available from: <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- UN Women. 2019. Facts and Figures: Women, Peace, and Security. Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#_Peace> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- African Union Commission. 2016. Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa. Available from: <https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/pubs/2016womenpeacesecurity-auc.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Guterres, A. 2019. Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280). Available from: <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- African Union Commission. 2016. Implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa. Available from: <https://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/pubs/2016womenpeacesecurity-auc.pdf>. [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Ibid.

- Monash Gender, Peace and Security. 2018. South Sudan: A Situational Analysis of Women’s Participation in Peace Processes. Monash University. Available from <http://mappingpeace.monashgps.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/South-Sudan-Situational-Analysis_ART.pdf> [Accessed 10 October 2020].

- Kirby, P. and Shepherd, L.J. 2016. The Futures Past of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda. International Affairs, 92(2), pp. 373–392. <https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/inta92-2-08-shepherdkirby.pdf> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- UN Women. 2015. Preventing Conflict Transforming Justice Securing Peace: Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/UNW-GLOBAL-STUDY-1325-2015%20(1).pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Tripp, A. 2015. Women and Power in Post-Conflict Africa. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Kirby, P. and Shepherd, L.J. 2016. The Futures Past of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda. International Affairs, 92(2), pp. 373–392. Available from: <https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/ia/inta92-2-08-shepherdkirby.pdf> [Accessed 5 October 2020].

- Scanlon, H. 2019. Women in Post-Conflict Resolution and Reconstruction in Africa. In: Spear, T. ed. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Boesten, J. 2014. Sexual Violence During War and Peace: Gender, Power, and Post-Conflict Justice in Peru Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guterres, A. 2019. Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280). Available from: <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Bastick, M., Grimm, K., and Kunz, R. 2007. Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict: Global Overview and Implications for the Security Sector. Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed forces. Geneva, Switzerland. Available from: <https://dcaf.ch/sites/default/files/publications/documents/sexualviolence_conflict_full.pdf> [Accessed 1 November 2020].

- TRIAL International. 2019. [Un]forgotten: Annual Report on the Prosecution of Sexual violence as an International Crime. <https://trialinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Unforgotten_2019.pdf>

- Ibid.

- Scanlon, H. 2019. Women in Post-Conflict Resolution and Reconstruction in Africa. In: Spear, T. ed. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- UN Women. 2019. Facts and Figures: Women, Peace, and Security. Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#_Peace> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- True, J. and Riveros-Morales, Y. 2018. Towards inclusive peace: Analysing gender-sensitive peace agreements 2000–2016. International Political Science Review, 40(1), pp. 27.

- Bell. C. and O’Rourke C. 2010. Peace Agreements or Pieces of Paper? The Impact of UNSC Resolution 1325 on Peace Processes and their Agreements. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 59(4), pp. 941–980.

- Ilesanmi, O. 2020 UNSCR 1325 and African Women in Conflict and Peace. In: Yacob-Haliso, O. and Falola, T. eds. The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies. London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 13.

- Ekiyor, T. and Wanyeki, L.M. 2008. National Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) in Africa: Needs Assessment and Plan for Action. Available from: <https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/cdrom/documents/Needs_Assessment_Africa.pdf> [Accessed 10 October 2020].

- Guterres, A. 2019. Conflict-Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280). Available from: <https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- UN Women. 2019. Facts and Figures: Women, Peace, and Security. Available from: <https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#_Peace> [Accessed 28 September 2020].

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2020. National-Level Implementation. Available from: <http://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/solutions/implementation> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

- Ibid.

- Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. 2020. Critical Issues. Available from: <https://www.peacewomen.org/why-WPS/critical-issues> [Accessed 28 October 2020].