The year 2015 marks the fourth anniversary of what is left of the so-called Arab Spring. Whether this anniversary is genuinely celebrated or passes by unnoticed remains to be seen. The reason is simple: for some actors, the past four years have been considerable disappointments, while for others, reason has prevailed over emotions. Given the two viewpoints, how then are we to analytically understand the dynamics of the so-called Arab Spring in North Africa?

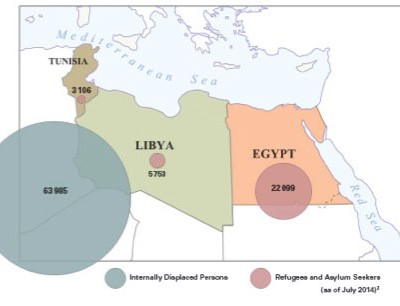

Broadly seen, two broad narratives exist that explain where the political developments in North Africa stand.1 On the one hand, there are those scholars and practitioners who have practically declared the revolts in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt as technically dead. The election in Tunisia in late October 2014 brought former members of the Zine El Abidine Ben Ali administration back into power; for Libya, scholars close to the armed conflicts literature would hardly disagree with defining the situation in the country as that of a civil war; and for Egypt, the ruling military elite continues to maintain its all-encompassing grip on power at the expense of democratic rule.

On the other hand, there are those who view the past years’ development in North Africa in a diametrically opposed way – by looking at developments in a very positive way. Albeit recognising that there have been instances of violence, abuses and atrocities against civilians in most of the North African states, political change has undeniably taken place. Tunisia, Egypt and Libya have taken major steps to reform previous system malfunctions. For example, all states in the region have made amendments to their constitutions to conform better to democratic practices and representations. Adding to this, most states have held elections without much international critique (although the disposal of former President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt will remain a thorn for the military). From this perspective, formal institutional democratisation measures have been taken and the liberalisation process appears to be on the right path.

In light of these two opposing viewpoints, it is pertinent to ask two sets of questions. First, why did the so-called Arab Spring actually turn out the way it did (what lessons were learned for any possible future processes of this kind)? Second, what challenges are we to witness in the future? To limit the scope of analysis, the remaining emphasis of this article will be on security developments in North Africa. Taking a security perspective – as opposed to reviewing political developments only – gives a strong explanatory basis for understanding what has been at stake, as well as what there is to expect in the years to come. The main argument pursued is that a new integrated framework is needed for the analysis of security-related events in North Africa.

Current State of Affairs

For the majority of ‘Arab’ and ‘African’ states affected by the Arab Spring, the political reform process has taken two steps forward and one step back. This is particularly true for political developments in Libya and Egypt. In Libya, Muammar Gaddafi’s authoritarian government was soon replaced by domestic turmoil in which militias with foreign backing were fighting each other (also resulting in profound negative impact for states in the Sahel). In Egypt, the military government regained control over the political system with an increase in oppression, notably against the Muslim Brotherhood and any other opposition group criticising the military. Nonetheless, a possible sign of positive progress is perhaps Tunisia, where institutional democracy has at least gradually deepened and non-violent talks have been held between political parties such as the Ennahda Movement and Nidaa Tounes. However, Tunisian society, in which the Arab Spring revolt unfolded, remains polarised and is expected to be so in the near-term years to come. This has partly to do with the fact that former members of Ben Ali’s administration are back in power.2 Meanwhile, political reforms in Morocco and Algeria have practically stood still as a result of the geopolitical rivalry that existed between the two political systems.

At the outset of the Arab revolt, the ‘end result’ of the turmoil that erupted in North Africa was clouded in uncertainty. Few analysts could foresee where things were moving. Four years down the road, however, one important lesson can be learnt on why the revolt turned out the way it did: the securitisation of the revolts and the subsequent geopolitical positioning of intraregional and inter-regional actors.3

From Peaceful Opposition to Securitisation

While Ben Ali, Tunisia’s president, disappeared from power relatively quickly, Hosni Mubarak, then president of Egypt, met his protesters with different political strategies to quell demonstrations. Unaware of the strength of the protests and that the army would turn its back on him, Mubarak underestimated his opponents by offering cheap political and economic concessions. Rather than co-opting his opponents, his political countermoves further fuelled grievances. For the United States (US), Egypt was most complicated, because of the country’s central role in its regional security architecture following the Camp David Accords (relaxing tensions between Egypt and Israel).4 In Libya, the demands were met almost immediately with full-scale violence by Gaddafi’s regime. What quickly came to add to the negative spiral of violence were both the fragility of the unique character of the Libyan state as well as the early realisation in the broader Middle East and the West that Gaddafi himself was an unreliable power holder, and therefore could be sacrificed for the sake of stability.5

Geopolitical Positioning

As the Arab revolt spread in 2011–2012, actors within and outside the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region began to take more proactive control over the security developments. The aim was to ensure that national interests prevailed. With this also came the switch in the Arab revolts dynamics: from being a local, peaceful and national protest phenomena to that of an arena for regional and international security actors. This positioning stood in sharp contrast to the early dynamics.

In 2012, several states in the region with more or less sophisticated policies tried to change internal political dynamics. Local actors and states gradually came to obtain increasing financial and military support. As the security concerns and political rifts spread and deepened, other actors stepped up their political, economic and military support. As a result, a number of political conflicts developed into war, and segments of the previously peacefully demonstrating population became radicalised. The dividing lines in the region have since become increasingly clearer – that is, with different interests manifesting at the local, national and regional level.6

In essence, then, an important explanatory factor for why the so-called Arab Spring in North Africa took form had to do with international actors’ positions and actions vis-í -vis local events. In this context, the role of US policies is particularly crucial.7 While the US was initially taken by surprise by the events in North Africa, it became increasingly clear that its national interests were given priority over its other principles on democracy and human rights. Put differently, Washington, DC regarded the Arab Spring as both a threat and an opportunity. During the early stages of the revolt, there was a policy position by the US administration to support the revolts, as a democratic transition would eventually strengthen the US-led security order in the region. The calculus was that geostrategic interests and democratisation were able to go hand in hand and mutually reinforce each other. This, in turn, may explain why the US came to accept the fait accompli in Egypt and Tunisia – that is, Ben Ali and Mubarak were forced from power. However, as seen over the past four years, US national interests prevailed over its more democratic and liberal-leaning aspirations. This has probably contributed to the often-ambivalent policy of the so-called Arab Spring. While US intervention in Libya clearly supported the rebels and was aimed at de facto regime change (through a ‘leading from behind’ strategy), the policy vis-í -vis Egypt was far more ambivalent. Sometimes support for the Muslim Brotherhood, and sometimes support for the Egyptian military (as well as support to both sides) complicated the US’s approach to the developments, not only in Egypt but also in other political trouble spots in the region.

In sum, the tumultuous and uncertain situation prevailing at the outset of the Arab Spring subsequently went on to become a process where the region’s various stakeholders actively came to position themselves for and against various scenarios. The revolts by freedom-aspiring citizens were overrun by geopolitical interests. This, in turn, led to the establishment of three competing visions or narratives of the Arab Spring: those in favour of continued democratisation; those calling for stability and the return to authoritarianism; and those accepting violence and confrontation for the purpose of securing a preferred geopolitical order.

Refocusing the Security Analysis

In light of the takeover of peaceful revolts by geopolitical considerations among inside and outside actors to North Africa, there is a clear need to start rethinking the conventional hard security paradigm and shift the limelight back on more human security and broad-based security concerns. The reason is simple: beyond the more immediate political challenges that states in North Africa face, there are a number of more profound structural security challenges looming on the horizon – challenges that unless addressed at an early stage are likely to have devastating social, political and economic consequences. To illustrate what these challenges are and how they play out, Egypt can be used as a case in point. However, any of the states in Africa or in the MENA region could experience the same challenges.

Having removed Morsi from power in July 2013, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) under General Sisi took on the goal of bringing security to the state, and effectively bringing the anti-terrorism agenda to the table. However, the military’s security priority in this regard may prove to be a fundamentally erroneous prioritisation, as all Egypt´s attention should be focused elsewhere. There are a number of structural factors that will have a considerable impact on Egypt’s long- term security and stability. The most pressing of these challenges include the explosive mix of a growing and more demanding population, increasing energy shortages, a near-term lack of adequate freshwater, increasing vulnerability to food insecurity, and negative impact of climate change.8

Egypt has one of the largest populations in the Arab world. One estimate suggests that about 81 million people live there. An estimated 63% of the population is aged between 15 and 64 years, and the youth cohort clearly dominates. The Egyptian population roughly doubled in size between 1980 and 2011, from an estimated 40 million people in 1980 to nearly 79 million people in 2011. The population is currently growing at an annual rate of 1.8% (estimated growth that is mostly occurring in urban areas).9 Hence, the stability of Egypt in the long term is related to its ability to meet the demands of its growing population, in particular with regard to economic growth, employment, energy supply and natural resources (food and agriculture). Although the demands of a young generation of citizens that aspire for integration in the globalised world may prove challenging in itself, Egypt’s growing population will likely require a new energy basis, which it does not have at the moment. The problem arises when population and energy factors are combined and understood in a more integrated security framework. With a growing population, the demand for energy will continue to rise. This will pose new costly challenges for Egypt, in addition to the social and economic challenges that the country’s citizens are currently experiencing. Put differently, the growing population in Egypt and the increasing demand by domestic and industrial consumption suggests that Egypt will face an energy shortage in the years to come. While Egypt is currently a net exporter of energy, it will soon become a net energy importer. In turn, Egypt’s energy shortage is also likely to affect its foreign relations (and thereby geopolitical interests) – not least its trade relations. However, the structural challenges do not stop here. The need to prioritise other structural challenges also came from additional considerations.

The potentially adverse impacts of climate change represent a long-term security challenge for Egypt. According to climate change data, North Africa is likely to suffer negatively in the decades to come. For example, the International Panel on Climate Change notes that the states of North Africa will be strongly affected by climate change, with regional temperatures set to increase by 2.5ºC during the winter months and 4ºC during the summer months.10 Meanwhile, precipitation levels are set to decrease by 20–30% during the winter and by about 40% during the summer.11 In this context, it is also likely that North Africa will experience more extreme weather events (note for instance that during December 2014, parts of North Africa were coated in snow).

As the challenges of population growth, increasing energy costs and changing climate systems merge and overlap, further social tensions could easily mount as a result. Although it is hard to imagine the citizens of Egypt demonstrating against their government for climate change issues, new political items on the agenda will arise. Linked to the structural challenges already discussed, food and water security challenges will rise on Egypt’s security agenda. For example, Egypt’s agricultural sector is very vulnerable to changes in natural precipitation. With a warmer climate this vulnerability is set to increase and less freshwater will be accessible. Since the water-intensive agriculture sector accounts for 85% of Egypt’s annual water use, limited access to freshwater will pose a significant challenge to its food production.12 With increasing water scarcity, the future looks bleak.13 In essence, then, all these long-terms scenarios are unwelcome news for a state struggling with domestic costs and profound social tensions, as its resources are already overstretched.

Summary and Conclusion

Having been entrenched in the Arab Spring turmoil, current as well as future regimes in North Africa will need to reshape the security agenda from hard security concerns to more profound and long-term security challenges. This is key – not only for Egypt, which simply serves as one example, but also for countries such as Tunisia, Libya and the other states in this part of Africa. To draw a telling parallel, the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa demonstrates how quickly new security concerns can enter as priorities on the political and economic agenda. Without making tough choices (for example, on national reconciliation) and making the right political priorities, minor crisis management challenges can easily turn out to be significant security concerns, threatening the sovereignty of the state and the social strata living within it.

Developments in North Africa have been turbulent and are likely to continue to be so in the years to come. The fourth anniversary of the epic turn taken by the freedom- and dignity-aspiring citizens of North Africa will be held in a milieu of continued geopolitical uncertainty. However, as suggested in this article, a new analysis is needed for those scholars and concerned practitioners who wish to understand what challenges North Africa faces. While much emphasis is placed on current political and economic transition processes, the conventional hard security paradigm through which these developments have been understood needs to be rethought. A new security paradigm is needed that takes into account some of the more structural security challenges that North Africa is likely to face in decades to come.

Endnotes

- Much has been written on the Arab Spring. See, for example: Ajami, Fouad (2012) The Arab Spring at One. A Year of Living Dangerously. Foreign Affairs, March/April; Dabashi, Hamid (2012) The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism. London: Zed Books; and Ayoob, Mohammed (2014) Will the Middle East Implode? Oxford: Polity Press.

- Based on Eriksson, Mikael and Bergenwall, Samuel (2014) Security in the Middle East and North Africa: a 5-10-perspective, FOI-R–4008–SE (Swedish Defense Research Agency, Kista).

- For more on the concept of securitisation see, for instance: Emmers, Ralf (2013) Securitization. In Collins, Alan (2013) Contemporary Security Studies, 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

- Based on Eriksson, Mikael and Bergenwall, Samuel (2014) op. cit.

- Meanwhile, in Morocco, demonstrators were met by the reform package, while Algeria managed to integrate parts of the opposition and thus undermine the popular protests.

- On the one hand, we see the political interests of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (anti-Muslim Brotherhood), while on the other, we witness the policies of Qatar and Turkey (pro-Muslim Brotherhood). Meanwhile, actors such as the US, European Union and Russia have pursued their own distinct approach.

- For more on US policies towards North Africa and the Middle East during the early turn of the Arab Spring, see Pollack, Kenneth M. et al (2011) The Arab Awakening: America and the Transformation of the Middle East. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Data in this section is based on the analysis presented in Eriksson, Mikael (2012) When Still Water Fizz: the Fall of the ‘Republican Monarchy’ in Egypt, FOI-R–3526-SE. Swedish Defence Research Agency, p. 79.

- Population data is found in United Nations. World Population Prospects, the 2010 Revision, World Population Prospects database and the World Population Prospects: The 2010, Volume II: Demographic Profiles is located at the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Available at: <http://esa.un.org/wpp/excel-Data/population.htm> [Accessed 10 January 2015].

- Haldén, Peter (2007) The Geopolitics of Climate Change, FOI-R–2377–SE. Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- Ibid.

- Sonnsjö, Hannes (2011) Regions Vulnerable to Climate Change. Findings and Methodological Considerations, Department of Defence Analysis, FOI-R- -3308–SE. Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- Ibid. pp. 75–76.