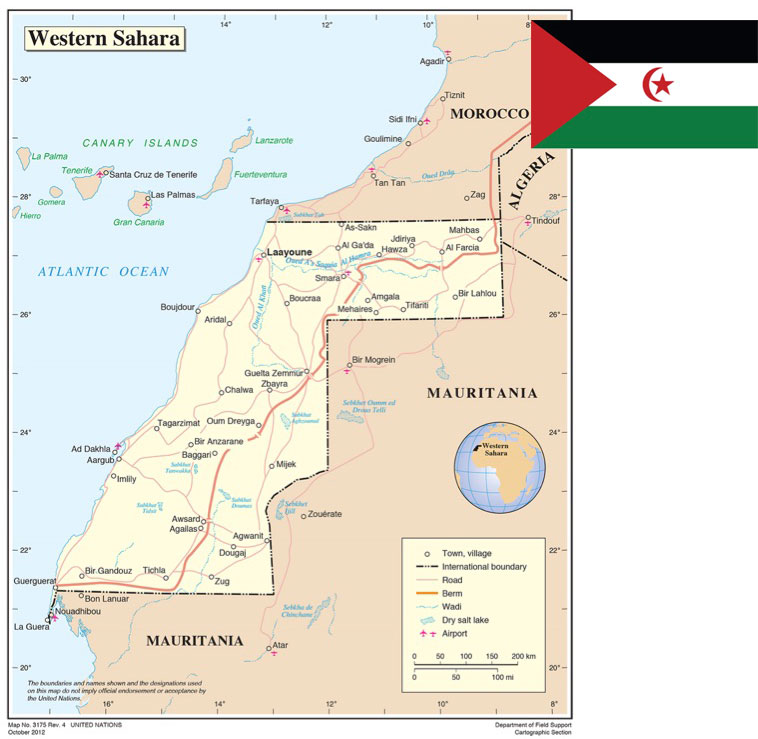

The revolutions that swept across North Africa and the Middle East have altered the political landscape in the region, and demonstrated that people-power revolutions can achieve change in a region that was often thought to be politically stagnant. Whether these changes can be deemed completely successful four years later is debatable, and varies on a case-by-case basis. A nearby territory that has been inspired by the Arab Spring is Western Sahara – a land that was annexed by Morocco and Mauritania1 in 1975, prior to the organisation of a referendum of self-determination by the United Nations (UN) as Spain completed its retreat from the territory. Local resistance to Morocco’s annexation was found among the Sahrawi people through their military arm, the Polisario Front, and government-in-exile, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR).

This article delves into the impact of the Arab Spring revolutions on the 40-year-old Western Sahara conflict. Four years after the revolutions were launched around Western Sahara, have there been spillover effects on the territory? First, the article tackles the notion that the Arab Spring was born on the outskirts of El Aaiún, during the Gdeim Izik protests. The article argues that although these protests were described as being precursors to the Arab Spring protests, they were actually the most prominent recent rallies against Morocco’s annexation of many that have occurred since 1975. The article then focuses on the fate of the territory since the Arab Spring began and highlights the continued struggle of the Sahrawi people to express dissent to Moroccan rule in the occupied territories, the continued curtailment of human rights in Western Sahara, and the status quo that has characterised the United Nations’ (UN) peacekeeping efforts. The article concludes with thoughts on the impact of the post-revolutionary political reshuffle in Libya and Egypt on the traditional stances adopted by these countries on the Western Sahara conflict.

Western Sahara: The Real Birthplace of the Arab Spring?

According to Noam Chomsky, the Arab Spring began in October 2010 when the people of Western Sahara revolted against their Moroccan occupiers.2 This opinion has been echoed by North Africa analysts, including Hicham Yezza, who commented: “In October 2010 – a few weeks before that fateful December encounter in Sidi Bouzid (Tunisia) between Mohamed Bouazizi and a municipal official – thousands of Sahrawi men, women and children set up Gdeim Izik, a camp a few miles East of Layyoune, the capital of occupied Western Sahara, in an act of mass protest against their continuing marginalisation under the decades-long Moroccan occupation of their land…”3

Gdeim Izik, as the protests began to be dubbed, succeeded in breaking the media embargo on Western Sahara, and images of a fiercely repressed peaceful protest were indeed reminiscent of those which were to follow in Tunis, Cairo, Tripoli and other Arab cities throughout the Middle East. Thousands of Sahrawis moved out of the cities of Western Sahara and into about 6 500 tents in the area of Gdeim Izik, outside the capital El Aaiún, to protest the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara and the ongoing discrimination, poverty and human rights abuses against Sahrawi citizens.4 Moroccan authorities dismantled the camps forcefully and blocked wounded Sahrawis from seeking medical treatment.5 In fear of the bad publicity that its activities could engender, Morocco expelled the Al Jazeera journalist sent to cover the events and closed the channel’s office in the country.6 The national airline, Royal Air Maroc, also impeded foreign correspondents from the Spanish television channels TVE and TV3, and from the Spanish newspaper El Mundo, from boarding flights from Morocco to El Aaiún, cancelling their flights in advance or blocking them at the airport.7 It is therefore difficult to find exact numbers of the casualties at Gdeim Izik, but it is estimated that at least several dozen Sahrawis lost their lives and hundreds were arrested. Among those detained were the ‘Gdeim Izik 25’ – 25 civilian Sahrawis who were convicted in a Moroccan military court on charges relating to violent resistance against security forces and forming criminal gangs. Nine of the men received life sentences, 14 received prison terms ranging between 20 and 30 years, and two were released after spending their two-year sentences in prison in court-ordered pre-trial detention.

That these events are reminiscent of scenes witnessed shortly after across North Africa is undeniable. However, in the words of Samia Errazouki: “If the ‘Arab Spring’ refers to the recent wave of popular uprisings throughout the region, rooted in socioeconomic grievances and the opposition to authoritarianism, placing the Western Saharan struggle on this spectrum is dismissive of a long history.”8 Defining the Western Sahara conflict as the Sahrawi people’s uprising against Moroccan authoritarian rule and unequal socio-economic opportunities indeed offers a limited perspective of the conflict. The Sahrawi people’s struggle is one for self-determination, as the Western Saharan territory’s decolonisation from Spain was never completed following Morocco’s annexation of the territory before a referendum of self-determination could be carried out by the UN. Elements of social unrest do exist in Western Sahara, as many Sahrawis feel that they are not given the same employment opportunities as Moroccan settlers in the region, and Sahrawis in the territory are treated with great distrust by the Moroccan authorities and suffer extreme restrictions on their freedoms of expression and association.9 However, Sahrawi protests in Western Sahara, while expressing dissatisfaction with the effects of Moroccan rule over the territory, largely contest this rule and demand the right of the Sahrawi people to carry out their overdue referendum of self-determination. In that, Gdeim Izik stands out in stark opposition to any of the Arab Spring uprisings and highlights the singularity of Western Sahara among the revolutions in North Africa.

Presenting Gdeim Izik as the spark that ignited the protest movement in Western Sahara is also an erroneous depiction. As important as that protest was to draw international attention to the Western Sahara problem, Gdeim Izik-like demonstrations have been occurring since Morocco occupied the territory – and continue to do so, away from the coverage of world media, as Morocco has blocked media from reporting on Western Sahara. Indeed, in the 1990s, the Sahrawis launched a series of protests that were labelled the ‘Sahrawi Intifada’. Starting in early September 1999, dozens of Sahrawi students organised a sit-in, asking for more scholarships and transportation subsidies to Moroccan universities. This evolved into constant vigils lasting 12 days in the square in front of the Najir Hotel in El Aaiún, which housed UN personnel. The protesters were quickly joined by former Sahrawi political prisoners seeking accountability for state-sponsored disappearances. The Moroccan authorities moved in to break up the sit-in, arresting dozens and reportedly dumping some in the desert miles outside of the town.10 Five days later, a larger demonstration with definite pro-referendum demands was dispersed by Moroccan authorities – this time through the unleashing of local gangs into the homes and places of business of the city’s Sahrawi residents – and a further 150 demonstrators were arrested.11

Six years later, following James Baker’s departure as the head of the UN mediation talks and the subsequent political standstill, tensions grew again, from 2004 to 2005. Frustrations arising at the lack of prospects for the holding of the much-anticipated referendum of self-determination exploded in May 2005. The protests began when it was discovered that Ahmed Mahmoud Haddi, a Sahrawi political prisoner known for his support for the Polisario Front, was to be transferred from a prison in El Aaiún to one in southern Morocco. His family members and other Sahrawi human rights activists staged a demonstration on 21–22 May 2005 outside the prison, which was forcefully dispersed by Moroccan authorities. This only spurred the protesters to return, in increased numbers and with more political demands. Pro-independence cries were shouted and SADR flags wielded. The Moroccan reaction was brutal, invading and besieging neighbourhoods to which the protests had spread, ransacking homes, forcefully dispersing the crowds and imprisoning dozens of activists. This inspired further protests in other cities in Western Sahara, namely Smara and Dakhla, and in the southern Moroccan cities of Tan Tan and Assa. Solidarity demonstrations were also organised throughout Morocco in the universities of Agadir, Marrakech, Casablanca, Rabat and Fez. The total number of political detainees quickly surged to over 100 in the space of a few days, and many of the detainees conducted hunger strikes in protest of their arrests. The protests and clashes with the police continued for months, and peaked in intensity in October 2005 when Moroccan security agents beat a Sahrawi demonstrator, Hamdi Lembarki, to death in full public view. Subsequently, a massive number of protesters, who unfurled SADR flags, gathered at his funeral.12

Western Sahara since the Arab Spring

Since Gdeim Izik, protests unbeknown to the international community continue to take place. Indeed, in April and May 2013, 10 days of protests took place across Western Sahara to call for self-determination after the UN Security Council voted to renew the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) without a human rights component, culminating in a protest on 4 May 2013 that saw thousands of Sahrawis taking to the streets to reiterate their call for self-determination. A few days later, on 9 May 2013, as another mass protest was being organised on social media, Moroccan police launched a wave of arrests and detentions aimed at nipping the growing movement in the bud. Amnesty International reported on the fate of six of the detainees and revealed that they had been the victims of severe torture.13

Since the beginning of the Arab Spring, human rights issues continue to surface regularly in the territory. A delegation from the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights (a US-based human rights organisation) undertook a visit to Western Sahara in 2012 and observed: “In Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, the overwhelming presence of security forces, the violations of the rights to life, liberty, personal integrity, and freedom of expression, assembly, and association create a state of fear and intimidation that violates the rule of law and respect for human rights of the Sahrawi people.”14 Subsequently, a British All-Party Parliamentary Group delegation visited the territory in February 2014, and declared in its report that it was made aware of major cases of human rights violations, including “several individual victims of extrajudicial execution by the Moroccan police; the ‘Gdeim Izik 25’ (…); the 15 young Saharawi men who ‘disappeared’ on 25 December 2005 and whose whereabouts are still unknown; the large number of activists arrested and ill-treated while in detention; and the crackdown on freedom of expression through intimidation and arrest of individuals trying to document or report on human rights violations in Occupied Western Sahara”.15 In 2014, Human Rights Watch observed repeatedly that Sahrawis who attempted to participate in demonstrations for self-determination were detained by Moroccan authorities and allegedly tortured during their interrogations to force them to sign confessions of wrongdoing.16 Despite these reports, MINURSO is one of the rare UN peacekeeping missions not to contain a human rights component to its monitoring activities, and annual efforts by the SADR to include such a component have been thwarted for years, as Morocco has resisted such an inclusion.

Finally, the UN’s efforts to resolve the conflict have not been fruitful since the Arab Spring. Since 2012, Christopher Ross, the UN Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy for Western Sahara, has had a tense relationship with the Moroccan government. Indeed, in April 2012, the Secretary-General delivered a report to the Security Council that contained recommendations from his Personal Envoy which offended Morocco (including one that called for adding a human rights component to MINURSO). Ross also stated that he wished to visit Western Sahara for the first time during his next trip to the region – a request that irked Morocco. Following these two events, the Moroccan government officially declared that it had lost confidence in the Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy, describing his work as “unbalanced and biased”.17 Although the UN Secretary-General communicated his continued support for his Personal Envoy to the Moroccan authorities, and Ross was able to make his first trip to Western Sahara, Morocco continues to be wary of his proposals, which are viewed as being partial to the Sahrawi cause. This has limited Ross’s ability to dialogue with the Moroccan authorities, and the frequency of his visits to Morocco has dwindled. After concluding nine rounds of informal talks with the parties to the conflict since August 2009, Ross declared that the two sides were no closer to a solution, and announced that he was halting informal talks and turning to shuttle diplomacy between the two sides to break the deadlock. Since it was launched in February 2013, Ross’s shuttle diplomacy has not yet succeeded in breaking this deadlock, and has yet to yield concrete results.

In a new turn of events, the African Union (AU), perceiving this lack of progress, has recently attempted to re-exert some control over the international community’s peacekeeping efforts in Western Sahara. Indeed, at its Executive Council’s 22nd Ordinary Session held in January 2013, the body requested that the AU Commission takes all necessary measures for the organisation of a referendum for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara. In a letter to the Secretary-General of the UN dated April 2013, the AU Commission’s chairperson, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, requested that Ross visit Addis Ababa “for an exchange of views with the Commission on the best way forward”.18 In addition, in 2014, the AU appointed its own Special Envoy for Western Sahara, Joaquim Chissano, the former president of Mozambique, to determine the best ways for the AU to support the international efforts aimed at finding a settlement to the Western Sahara conflict.19 Chissano began consultations with the permanent members of the UN Security Council, UN officials and Spain, and is expected to produce a report for the AU’s 24th Summit of Heads of State and Government in January 2015. Although the UN is not likely to take a backseat to the AU on this issue, the AU’s efforts are meant to put pressure on the UN and the parties to the conflict – in particular, Morocco – to organise the long-overdue referendum of self-determination in Western Sahara.

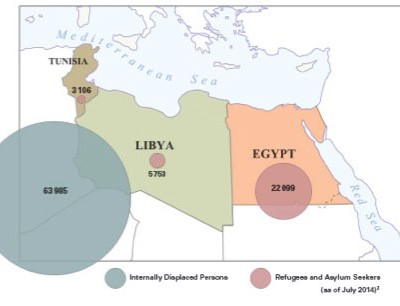

The Effects of the Libyan and Egyptian Revolutions on Western Sahara

Since its inception, the Western Sahara conflict has been characterised by an international diplomatic tussle between the SADR and Morocco for the recognition of their stances by third parties. The battle for recognition of the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination or Morocco’s claim over the territory is one that is waged country by country, and after the Arab Spring toppled trusted allies, both Morocco and the SADR launched diplomatic campaigns to claim or reclaim allies in Libya – a supporter of the SADR under Gaddafi – and Egypt – an advocate of Morocco’s claim over Western Sahara under Mubarak.

In the case of Libya, Gaddafi’s regime was closely tied to the conflict for a significant period of time. In fact, Libya was the first and biggest supporter of the Polisario Front at the outset of the conflict, even sending arms to the resistance movement during the early years of the war. Gaddafi’s support waned, however, particularly after the signature of the Treaty of Oujda, which for a short time linked Morocco and Libya in a union.20 However, once that project fell through, Gaddafi resumed his assistance to the Sahrawis – albeit not as enthusiastically as in the early days of the conflict. His assistance included offering humanitarian aid to the Sahrawi refugee population in Tindouf, Algeria. Politically, Libya was one of the countries that sent a letter to the Organisation of African Unity’s Secretary-General in July 1980, supporting the admission of the SADR into the organisation. In later years, Gaddafi was firm in his rejection of the Moroccan Autonomy Plan,21 stating that the Sahrawis should be able to choose one of two options through a referendum: integration within Morocco or independence.

When Libya’s revolution began, the Moroccan government quickly aligned itself with the National Transitional Council (NTC) and not Gaddafi’s flailing regime, in the hope that the new establishment in the country would remember Morocco’s early recognition of the Libyan revolutionaries, which was made in August 2011, and return the favour by lending its support to the Moroccan claim over Western Sahara. An official visit was organised in the same month by the Moroccan foreign minister, Taieb Fassi Fihri, to the revolutionaries’ capital city, Benghazi. This was the first visit by an Arab foreign minister to the rebel stronghold since the beginning of the Libyan uprising.

Morocco also sought to create a rift between the revolutionaries and the Polisario Front. It claimed on the website Polisario Confidentiel, linked to the Moroccan secret services, that the Polisario Front had sent hundreds of Sahrawi mercenaries to Libya, and these mercenaries were paid US$500 a day by the Libyan regime to support Gaddafi.22 In reaction to this claim, the SADR’s press agency, the Sahara Press Service, published an article quoting the former president of the NTC denying these allegations.23 In the wake of the changes that occurred in Libya, Polisario Front members also expressed hope that their cause would be championed by the new leadership in the country. Indeed, during the 13th edition of the Polisario Front’s annual congress, which was themed around the Arab Spring, the SADR representative to the AU, Sidi Mohamed Omar, stated that he hoped that “[t]he winds of change which are blowing over these states will benefit the Sahrawi cause… [including by] building more fraternal and solid relations with our brothers from these Arabic countries, including Libya.”24

In the case of Egypt, the relationship between Morocco and Egypt has recently undergone turbulent times. The origin of this turbulence is a host of critical Egyptian media reports on Morocco, the last of which criticised King Mohammed VI’s use of five airplanes during his last trip to Turkey.25 In turn, in early 2015, Morocco’s media launched a critical campaign against Egypt, and President Al-Sisi in particular, labelling the ousting of President Morsi “a coup which put a halt to a democratic process” on the state-owned Al Aoula channel, and implying that Al-Sisi’s election was flawed, due to the 25 million Egyptian electors who did not partake in the vote.26 This statement came in stark contrast to Morocco’s position following Morsi’s ousting – the country was one of the first to congratulate Interim President Adly Mansour two days after Morsi’s removal.

In the wake of Mohammed VI’s visit to Turkey, with which Egypt has a strained relationship, Egyptian authorities showed signs of a rapprochement with the SADR, making it seem as though the ambivalent relations between the two countries could cost Morocco Egypt’s traditional support on the Western Sahara issue. Indeed, Egypt allowed itself to be wooed by the SADR, which invited Egyptian journalists to the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, in June 2014.27 This visit was followed by another, more official one, in October of the same year, in which an Egyptian delegation headed by the undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture visited the camps in Tindouf and met with the SADR president, Mohamed Abdelaziz.28 However, on 16 January 2015, Morocco and Egypt mended fences during the Egyptian foreign minister’s visit to Morocco, where he was received by his Moroccan counterpart as well as the king of Morocco. During these exchanges, Morocco was assured by the Egyptian minister of his country’s continued support for Morocco’s autonomy proposal for Western Sahara.29

As things stand, it is not yet clear whether post-revolutionary Libya will continue to support the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination, as Gaddafi had for decades – but in the case of Egypt, the current post-revolutionary government has decided to continue to support the Moroccan position, as the kingdom seems to have succeeded in discouraging Egypt from balancing its position to salvage the relationship between the two nations.

Conclusion

The political changes brought about by the Arab Spring have given the Sahrawis hope that their own hardships might eventually come to an end. The Sahrawis were undoubtedly inspired by the people-power revolutions taking place around them, and reassured that they would also eventually achieve what their neighbours obtained – the right to a political voice. The fact that the wave of revolutions was encouraged and even materially supported by Western powers further drove the Sahrawis to wonder why their neighbours, in such a short span of time, could obtain what they had been fighting for, for decades. This sentiment was further exacerbated by the birth of a fellow African nation, South Sudan, in 2011, following a referendum monitored by the international community. As demonstrated in this article, for now, the Western Sahara conflict remains at a standstill, as it is left behind in the wave of political revolutions in North Africa – much as it is was left behind during the era of decolonisation. Western Sahara seems doomed to remain the exception to the rule in these sweeping international political trends, and as much as it predates the Arab Spring, will probably outlast it unless decisive action is taken to resolve the conflict fairly, once and for all.

Endnotes

- Mauritania renounced its claim on Western Sahara in 1979 after a four-year war against the Polisario Front.

- Chomsky, Noam (2011) ‘Noam Chomsky and Western Sahara’, Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTjOt0Pz0BQ> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Yezza, Hicham (2013) ‘Gdeim Izik: The First, Forgotten Spark of the Arab Uprisings’, Available at: <http://www.opendemocracy.net/hicham-yezza/gdeim-izik-first-forgotten-spark-of-arab-uprisings> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Human Rights Watch (2010) ‘Western Sahara: Beatings, Abuse by Moroccan Security Forces’, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/11/26/western-sahara-beatings-abuse-moroccan-security-forces> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Ibid.

- Ruiz Miguel, Carlos (2010) ‘Gran Nerviosismo del Majzén Marroquí’, Available at: <http://blogs.periodistadigital.com/desdeelatlantico.php/2010/10/30/gran-nerviosismo-del-majzen-marroqui> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Ibid.

- Errazzouki, Samia (2012) ‘Chomsky on the Western Sahara and the “Arab Spring”‘, Available at: <http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/8093/chomsky-on-the-western-sahara-and-the-%E2%80%9Carab-spring> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- US Department of State (2006) ‘Western Sahara’, Available at: <http://m.state.gov/md61702.htm> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Damis, John (2001) Sahrawi Demonstrations. Middle East Report, 218, p. 40.

- Ibid.

- Zunes, Stephen and Mundy, Jacob (2010) Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, pp. 151–155.

- Amnesty International (2013) ‘Urgent Action: Six Tortured and Detained in Western Sahara’, Available at: <http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE29/006/2013/en/205f8f4e-bdb2-430e-a871-2c4df85e27d0/mde290062013en.pdf> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights (2013) Nowhere to Turn: The Consequences of the Failure to Monitor Human Rights Violations in Western Sahara and Tindouf Refugee Camps. Washington, DC: Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, p. 5.

- UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Western Sahara (2014) Life Under Occupation: Report of a Delegation of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Western Sahara to the Occupied Territory of Western Sahara. London: UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on Western Sahara, p. 7.

- Human Rights Watch (2014) ‘Morocco/ Western Sahara: Fair Trials Elusive. Court Ignores Torture Allegations’, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/09/moroccowestern-sahara-fair-trials-elusive> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

Human Rights Watch (2014) ‘Morocco: Sahrawi Activist Facing Military Tribunal. Promised End to Such Trials for Civilians Not Yet a Reality’, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/12/22/morocco-sahrawi-activist-facing-military-tribunal> [Accessed 30 January 2015]. - Aït Akdim, Youssef (2012) ‘Maroc: le Sahara Occidental et le Cas Christopher Ross’, Available at: <http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/JA2683p042-043.xml0/> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Dlamini-Zuma, Nkosazana (2013) ‘Letter to the Secretary- General of the United Nations’, Available at: <www.innercitypress.com/ws1au2banicp0413.pdf> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Sahara Press Service (2014) ‘Morocco: Ex-President Joaquim Chissano, New AU Special Envoy for Western Sahara’, Available at: <http://allafrica.com/stories/201406301323.html> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- The treaty, which was signed in August 1984, created a short-lived union of states between the two countries.

- Morocco submitted its autonomy proposal to UN Secretary- General Ban Ki-Moon in April 2007 as an alternative solution to organising a referendum of self-determination. The plan proposes to establish Western Sahara as an autonomous region within the Moroccan state.

- Polisario Confidentiel (2011) ‘Exclusif: Un Bataillon de Combattants du Polisario Revient de Libye’, Available at: <http://www.emarrakech.info/Exclusif-un-bataillon-de-combattants-du-Polisario-revient-de-Libye_a57762.html> [Accessed 22 October 2013].

- Sahara Press Service (2011) ‘Libyan Transitional National Council Denies Any Presence of Polisario Front or Assistance to Gaddafi’, Available at: <http://www.spsrasd.info/en/content/libyan-transitional-national-council-denies-any-presence-polisario-front-or-assistance-gadda> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Resistencia Saharaui (2011) ‘Congreso del Frente Polisario Trata Sobre Primavera Arabe’, Available at: <http://resistenciasaharaui.saltoscuanticos.org/2011/12/19/congreso-del-frente-polisario-trata-sobre-primavera-arabe-2/> [Accessed 22 October 2013].

- Aggar, Salim (2015) ‘Ca Chauffe entre Rabat et le Caire’, Available at: <http://www.lexpressiondz.com/actualite/208233-les-dessous-d-une-guerre-mediatique.html> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Jaabouk, Mohammed (2015) ‘Maroc: L’Egypte S’Approche du Polisario et ses Médias Attaquent le Roi…‘, Available at: <http://www.afrique-asie.fr/menu/maghreb/8709-maroc-l-egypte-s-approche-du-polisario-et-ses-medias-attaquent-le-roi.html> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Alami, Ziad (2015) ‘MINURSO: La Nouvelle Stratégie du Polisario’, Available at: <http://www.le360.ma/fr/politique/minurso-la-nouvelle-strategie-du-polisario-29209> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Galal, Rami (2015) ‘Tensions Increase Between Egypt, Morocco’, Available at: <http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/01/egypt-morocco-relations-tension-media.html#> [Accessed 30 January 2015].

- Jaabouk, Mohammed (2015) ‘Sahara: L’Egypte d’Al Sissi Soutient la Proposition Marocaine d’Autonomie ‘, Available at: <http://www.yabiladi.com/articles/details/32681/sahara-l-egypte-d-al-sissi-soutient.html> [Accessed 30 January 2015].