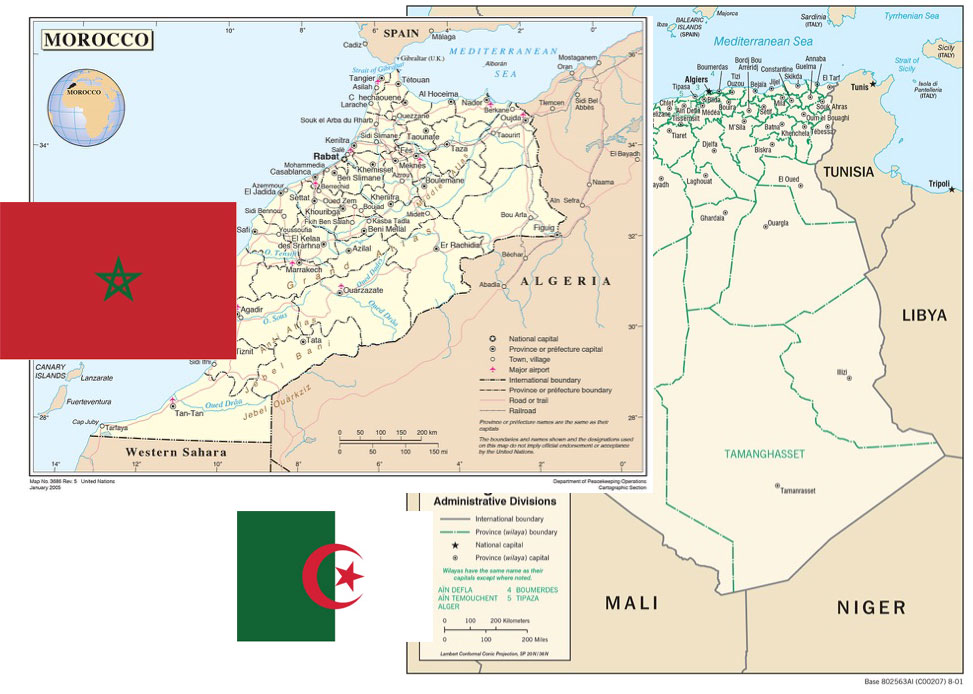

While what was termed the ‘Arab Spring’ and ‘Arab Revolutions’ were in full swing in 2011, Morocco and Algeria sailed safely through the strong winds of change and avoided the serious clashes and violence experienced elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. They appeared to have done so thanks to gradual reform processes, among other things, which helped avoid unsettling revolts. In these two countries, street protests in 2011 were relatively limited, and the countries’ national leaders were at no time targeted for removal or even condemnation. Morocco and Algeria became ‘the exceptions’ in a region engulfed by violent protests and instability.

This article examines why Algeria and Morocco did not experience social upheavals in 2011 and thereafter, in spite of the fact that their respective societies have enough grievances against their respective political and economic systems to prompt some revolt. It also discusses the extent to which the nature of the two ruling regimes and their evolution since the early 1990s can help explain why these two countries did not experience the disruptive and destabilising revolts seen in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and Yemen. Finally, the article examines whether these two countries will (a) evolve in the near future without much disruption and social upheaval, (b) finally join the list of MENA countries whose economic, social and political systems have been violently contested by the masses in recent years, or (c) experience yet another clever adaptation of the authoritarian rule to the challenges of the day.

For important reasons, the expression ‘Arab Spring’ will not be used here.1 Other expressions will be used instead, such as ‘popular revolts,’ ‘mass protests,’ and ‘social upheavals’. The social upheavals of 2011 are understood as a mass protest (peaceful or violent) against existing political and economic systems, rulers and policies in the Arab region; the 2011 protests were persistent, vocal, peaceful or violent, and either challenged the status quo or aimed for regime change.

The revolts, which began in December 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, and culminated in the overthrow of the presidents of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, challenged political systems and leaders that failed the people in many ways. They were against the social and economic conditions that deprived many people while a few predators, thanks to privileged connections to the state, became illicitly wealthy and grew contemptuous toward the rest. Finally, the upheavals constituted a rejection of the post-colonial order that was characterised by an autocracy whose survival depended on being compliant with, and subservient to, the wishes and interests of former colonial masters (mainly France in North Africa and the United States (US). This post-colonial order was maintained in the Arab world for many decades after the end of formal colonialism. The 2011 revolts in North Africa and the Middle East were more about these multiple rejections than just a clash between authoritarian states and unemployed youth.

The upheavals made some people wonder whether the Arab countries have finally entered the third wave of democratisation that Samuel Huntington outlined in his 1993 book, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century.2 However, post-2011 developments do not seem to confirm that – except perhaps for Tunisia, which appears to be on the way to some substantial change. Beyond the debate generated by Huntington’s view on the absent democracy in the Islamic world, which is discussed elsewhere,3 it is undeniable that most of the MENA region was not substantially affected by the three waves of democratisation in the West and beyond – that is, until now. As will be discussed here, in Morocco and Algeria the reform processes have been limited to minimal political liberalisation in spite of – or maybe because of – the turmoil that spread in the region since 2011.

The Moroccan and Algerian Contexts

Since their independence from colonialism, Algeria and Morocco achieved important progress in economic and human development. The 2010 Human Development Report placed them in the 10 ‘top movers’ – that is, countries which achieved the greatest improvements in human development since 1970.4 However, in spite of a relatively positive Human Development Index (HDI), both countries lag in social and economic development and cannot keep up with their growing populations and income disparities. The external pressure for economic liberalisation and the effect of global economic shocks and other factors made it difficult for Algeria and Morocco to maintain welfare systems and distributive policies dictated by some form of post-independence social contracts. These factors, in combination with neo-liberal policies promoted by international institutions, pushed the two states to lessen their role in the economy by privatising public companies, limiting subsidies and lifting price controls.

While Algeria remains highly dependent on the export of oil and gas whose price fluctuations it does not control, Morocco – a non-hydrocarbon country – has a little more diversified economy, but is still heavily dependent on the export of phosphates. It is highly vulnerable to rising international competition and demand fluctuations for its key export products. Stringent structural adjustment programmes sponsored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in Algeria and Morocco had some success at the aggregate level, but they did not alleviate the poverty and unemployment experienced by many people, especially the youth. The difficult socio-economic conditions of many people were made even more untenable by large-scale corruption, cronyism, nepotism and limited freedom to express grievances and demands.

Over the last three decades, the governing regimes of the two countries faced serious and long-standing complaints against authoritarian systems that abused power openly and with impunity, limited individual liberties, treated citizens with disdain and condescendence (referred to as hogra in popular parlance in Algeria), neutralised political opposition by way of repression and co-optation, limited the means of free expression, inhibited the accountability of institutions and individual power holders, allowed the judicial system to serve the powerful at the expense of the weak, produced meaningless elections and institutions of representation, and used rent from natural resources (gas and oil for Algeria and phosphates for Morocco) to quiet occasional social unrest without reforming.

Both states perfected their coercive capacities and their effectiveness; the pervasiveness of coercion increased in recent years, especially with (a) increased violent actions by radical Islamist groups roaming the Maghreb and the Sahel (for example, al-Qaeda of the Islamic Maghreb – AQIM), and (b) participation in the ‘global war on terror’ (GWT) initiated by the US after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. These two factors enabled the security services of the two countries to impose more limits on political dissent. Morocco also became a destination country for the policy of ‘extraordinary rendition’5 enacted by the US government under George W. Bush.

Many of the social, economic and political conditions that have been outlined were also present in the MENA countries that experienced social upheavals in 2011. Since they did not generate a revolt wherever they were present, this series of common conditions cannot alone explain why upheavals occurred in some countries (Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Bahrain and Yemen), and not in others (Morocco and Algeria). Additional explanatory factors may include trigger events, such as the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouaziz in Tunisia, and the way a government responds to spontaneous mass protests.

Explaining the Algerian and Moroccan Exceptions

Both Morocco and Algeria were not totally immune to the social upheavals in the region in early 2011. On 5 January 2011, Algerian youth engaged in a series of riots in many cities and towns. These riots were triggered by both a sudden rise in the price of basic food and the events in Tunisia. The rioters had no specific political demands. In Morocco, the main trigger was the protest in Tunisia, combined with prevailing social, economic and political grievances.

Unlike the Algerian riots, the Moroccan protest that began on 20 February 2011 featured specific political demands but did not target the monarch himself. They were aimed at the overall unsatisfactory political and economic conditions and at the Makhzen, which is the informal centre of power that stands behind the façade of the modern state – it is powerful and feared.6 The massive but peaceful demonstrations started in the capital city of Rabat, and were youth-led and inspired by social media. The protesters demanded an end to corruption, jobs for the unemployed youth, and constitutional reforms that curtailed the powers of the monarch and increased those of elected representative institutions.

In both countries, the street protests ended or died out slowly after the leaders addressed some of the immediate grievances, thereby avoiding an escalation of the situation. Algeria and Morocco did not experience the kind of violent and sustained upheaval witnessed elsewhere, partly because the leadership reacted swiftly with proactive policies meant to appease people ahead of an almost-certain storm. Another equally important reason as to why the region’s winds of upheaval did not unsettle these two countries was that both had been engaged in gradual political reforms for more than a decade. These reforms did not affect the authoritarian nature of the two regimes, but they set them apart from the much harsher autocratic rule that existed in Libya and Tunisia before 2011. For example, in North Africa, only Algeria and Morocco had integrated opposition parties – both religious and secular – in the political process for a decade at least. Furthermore, Algerian and Moroccan citizens have been enjoying relatively more political freedom than in most other Arab countries. However, high youth unemployment and wide- scale corruption made them disillusioned and resentful. Once social upheaval was underway in several countries, it inspired similar protest movements in the two countries, but they were short-lived and limited in their scope.

The two countries quickly acted to limit the contagion effects on their respective populations by enacting some reforms and promising others, by preventing the rise of basic food prices, and by maintaining subsidies on essential products and services. Also, the security services were ordered to avoid any provocation that could trigger a social explosion. Moreover, the leaders of the two countries often pointed to insecurity problems and disruptions caused by social unrest in the region (without specifically mentioning Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Syria and Yemen) as things they and their people did not wish to see happen in their countries.

As the early utterances of protest in Morocco and Algeria were quieted relatively easily and peacefully, their authoritarian regimes – one a republic and the other a monarchy – continued to give the impression of being engaged in constant political liberalisation, while in fact maintaining the status quo on many fronts.

Algeria: A Precarious Stability

The Algerian authorities reacted negatively to the unrest in the region by pointing to instability in Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria and Yemen as a strong reason for not falling ‘victim’ to the ‘Arab Spring’, which was presented as a ploy by foreigners to cause instability in the Arab world. At the same time, they used substantial financial resources to satisfy the demands expressed by the rioters in early January 2011, and promised political reforms at a later time. Algeria thus remained mostly unaffected by this ‘Spring’ of upheavals, and up to today has not yet engaged in any substantial reform.

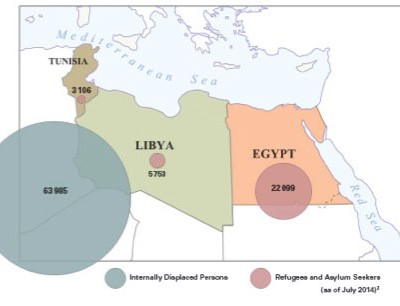

Algeria, just like Morocco, had already enacted some reforms long before the upheavals of 2011, not after. The reforms began in the late 1980s following a major popular upheaval in October 1988, when wide-scale youth riots shook the country (500 young people were killed within a few days by military repression).7 These events – the first of their kind in the region – pushed the authoritarian regime to open the public sphere to mass political participation through changes to laws on associations, parties and the media. By 1989, substantial political liberalisation brought about the end of the one-party system and the establishment of multiparty elections, and freedom of association and of the press. However, this substantial political opening was slowly recanted in the name of security, due to the raging Islamist rebellion that lasted from 1992 to the early 2000s. Armed rebellion began after the first multiparty parliamentary elections were cancelled in January 1992 by the military, when the Front of Islamic Salvation (FIS) appeared about to achieve a landslide victory. In that war of 10 years, 200 000 people died, economic and social infrastructure was destroyed and 1.5 million people were displaced.8

In that context, all political opposition was dispersed by intimidation, repression or judicial action, or co-opted. However, in spite of this, Algeria has maintained a formal multiparty political scene and a lively independent press. Political liberalisation stalled in the 1990s, but that was not a reason in itself to get people to challenge the system again, so soon after the bloody decade.

The riots of early January 2011 did not have explicit political demands, and the rioting Algerian youth – unlike the Tunisian ones – did not get the support of labour unions, political parties or civic associations. The events lasted only a week, and ended as soon as the government imposed a low price ceiling on basic food, tabled impending market regulations and provided “temporary and exceptional exemptions on import duties, value-added tax and corporate tax for everyday commodities”.9 In other words, the economic demands received an immediate regulatory response.

Political demands were finally expressed by a series of peaceful protests that were started on 12 February 2011 by the newly created National Coordination for Change and Democracy (CNCD), an organisation formed in January 2011 and made up of small parties, the National League for the Defense of Human Rights, and other civic associations. In spite of a large police contingent preventing demonstrations in the capital, a small number of protesters demanded democracy, an end to the 19-year-old state of emergency, and the release of people arrested during the January 2011 riots. The protest, which did not target President Abdelaziz Bouteflika but the behind-the-scenes true power holders in Algeria, collectively known as Le Pouvoir, and the authoritarian regime. Le Pouvoir includes army generals, old leaders of the National Liberation Front (FLN, which was the sole legal party from 1962 to 1989) and powerful business magnates, who enjoy de factor business monopolies, access to state resources, and a privileged relationship with the regulatory state bureaucracy.

The weakness of these peaceful demonstrations and their lower turnout was due to governmental restrictions, as well as the fact that Algeria was still healing from the 10-year war of the 1990s. Another reason for the weak appeal of the protest movement was that its key figure was the leader of the Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD), a party that has considerable support in the mostly Berber region of Kabylie to the east of the capital, and not much elsewhere. The RCD supported the government’s cancellation of the 1991 elections when the Islamists won the first round, and welcomed the repression of the victorious religious party, the FIS.

Under some domestic and international pressure, the government legalised more parties and increased the female quota in parliamentary elections. As a result, 21 new parties were legalised, diluting further both the overall political opposition and the Islamist formations. A new gender quota system for electoral lists and parliament seats helped elect 145 women to parliament in May 2012 – 31% of the 462 deputies of the National Assembly, up from a mere 7%.10

With a pro-government coalition made up mainly of two conservative parties (FLN and National Democratic Rally, RND) that qualified the ‘Arab Spring’ as a foreign ploy, a parliament that is still a rubber-stamping machine for the president and his government, a president himself who is ill and regularly absent from public view, and a military establishment that is still a key holder of political power, Algeria does not seem to be heading toward substantial reforms. The governing system remains authoritarian – albeit softened a bit by the 10-year war and concerned about the possible impact of violence and unrest in neighbouring Libya and Mali.

Morocco: Status Quo with Limited Reforms

Gradual political reforms started in small steps during the reign of the late king Hassan II, who ruled his country with an iron fist for 38 years (1961–1999). After he died in 1999, his son King Mohammed VI deepened some of those reforms – the latest being the constitutional changes enacted in July 2011 in response to street protests. Since ascending the throne, the new king enacted several reforms, such as changes to the moudawana (family code) in 2004, which improved the legal status of women, and programmes aiming to alleviate poverty and illiteracy. These moves earned him the title of ‘king of the poor’, and helped enhance his legitimacy – even if these moves did not actually improve living conditions or create jobs.

The constitutional change of 2011 did not diminish the political, religious and economic powers of the monarch. The new constitution affirmed the separation of powers by reinforcing the authority and autonomy of the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. The government is no longer responsible to the king, but is exclusively accountable to parliament – in theory, at least. The prime minister, who was previously handpicked by the king, is now appointed from the party that controls the most seats in parliament. The scope of the legislature’s areas was increased, the role of the opposition was reinforced, and the independence of the judiciary was affirmed. The constitutional changes, which did not affect the substantial authority of the monarch, were approved by referendum on 1 July 2011. In spite of that, demonstrators continued to demand economic reforms and an end to the endemic corruption.

New parliamentary elections, held on 25 November 2011, produced a government led by the Islamist party Justice and Development (PJD) in alliance with three secular parties: Istiqlal (PI), the Popular Movement (MP) and the Party of Progress and Socialism (PPS).11 The PJD won the most seats in parliament (107 of 395) and became the de facto number one party in Morocco.12

The PJD became the only hope for substantial changes after the traditional opposition (nationalists and the left) was weakened by many years of repression, wide-scale co-optation and internal divisions. However, this Islamist party quickly found itself in a bind as it headed a coalition government, under the supervision of the monarch: to remain popular among its constituency, the PJD had to challenge policies and the institutional setting, and this may have entailed taking on the Makhzen – and maybe the king himself.

Abdelilah Benkirane, the party’s leader and prime minister of Morocco, decided at the outset to focus on social and economic issues and on corruption – major points of contention raised by the 20 February Movement. He has avoided questioning – for now, at least – the institutional order or take on the Makhzen and the big private sector leaders, all of which are seen by many people as major obstacles to change.

The wave of upheavals across the region pushed the Moroccan monarch to accommodate the vocal protest movement through inconsequential constitutional changes, the promise of economic reforms and more co-optation. The king also allowed Benkirane’s moderate, pro-monarchy, Islamist party to head the government, as a way to contain the Islamist sentiment and the protest movement, especially when the traditional secular opposition – mainly of the left – saw its popularity decline steadily in recent years.

While political liberalisation has progressed since the late 1990s, the essential character of Morocco’s governing system remains authoritarian, albeit with a monarch who is popular and seemingly benign.

Piecemeal Reforms and Authoritarian Continuity

In the study of authoritarianism, many questions still elude scholars, especially in light of the recent and rapid collapse of ‘robust’ authoritarian systems in the Arab world, to everyone’s surprise.13 The questions include: Why does authoritarianism persist for a long time in one country or region and not in others? What helps it resist internal and external challenges, and how? What factors can end it, and when? Answers to these questions may be possible through a study of the recent revolts that unseated four long-time Arab rulers within a year. Such a study could also explain the persistence of authoritarianism, in spite of the downfall of rulers or the enactments of a series of reforms such as those discussed previously.

In the face of resilient authoritarianism in many parts of the world, including the MENA region, some scholars and keen political observers created conceptual shades of authoritarianism to explain the longevity and adaptation of this phenomenon.14 These conceptual shades (for example, ‘illiberal democracy,’ ‘liberalised autocracy’ and ‘semi-authoritarianism’) have been used to characterise authoritarian regimes that, under pressure, enacted some political liberalisation without changing fundamentally.

As discussed previously, Algeria and Morocco have not moved away from the authoritarian pattern of governance, in spite of some enacted reforms and policy accommodations when faced with potential upheaval. They merely seem to be going through an adaptation of the authoritarian rule to the circumstances of the day through limited acts of political liberalisation, rather than democratisation.

Political liberalisation, as defined elsewhere, is “a process that gradually allows political freedoms and establishes some safeguards against the arbitrary action of the state”.15 It is only a preliminary set of conditions for democracy. Democratisation is the intermediate stage between political liberalisation and democracy; it is “a higher level of political opening, a process through which state control over society is slowly diminished to a point where the state becomes less arbitrary and more prone to bargaining with key groups representing differentiated social, economic, and cultural interests. At this stage, the state tends to progressively resort less to command governance and more to negotiated public policies.”16

Democratisation may enhance the state’s legitimacy and may help society acquire greater autonomy and say in public policy.17 Both Algeria and Morocco are still far from that, and their ability to shun serious and much-needed changes may diminish in the coming years if the rising expectations of their citizens do not get a matching response from the state.

The Prospects of Change

If things do not improve substantially for the average Algerian and Moroccan in the coming years, these two countries’ approach of gradual and superficial change will show its limitations and may not hold off a serious contestation. With some good foresight, the two countries could avoid more difficult times by taking adequate and lasting actions on several fronts. They should curtail the use of rent (from hydrocarbons and phosphates, remittances, foreign aid and so on) as an instrument of state dominance over society, of personal power, and of select group privileges. Of equal importance is the need for blind and equal justice for all and a strong system of accountability for all office holders – even monarchs. To avoid the perennial tenure of office holders, free and multicandidate elections must be held on a regular basis and be monitored by independent institutions. These conditions, which are not yet established or consolidated in the two countries or in the rest of the MENA region, will take time and persistent efforts to realise.

The two countries are under strong domestic pressure for serious reforms. There are also external pressures from regional dynamics and contingencies, as well as extra-regional pressures, such as the actions and roles of great powers in the current turmoil in the Maghreb and Middle East. Because future developments in the MENA region will be affected by many internal, regional and international factors, it is not easy to predict what will happen in Morocco and Algeria as they muddle through the effects of the ‘Spring’ of Arab upheavals. Stringent, essential and necessary economic reforms are needed to maintain the momentum of change. Genuine political reforms are equally needed. Such reforms are crucial to relative stability in these trying moments.

Endnotes

- The phenomenon to which the expression ‘Arab Spring’ refers might be misconstrued and misunderstood in academic and media publications, as it tends to relay more what is wished than what is actually happening. Also, the word ‘Arab’ in the expression ‘Arab Spring’ tends to exclude those who have rebelled but do not share the Arab identity, such as the Berbers of North Africa.

- Huntington, Samuel P. (1993) The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 19. The first wave started in the 19th century in Western Europe and North America; the second wave began after World War II in Europe and swept away dictatorships that came to power before and during the war; and the third wave started in the mid-1970s and affected Latin America, Spain, Portugal and, more recently, Eastern Europe. It has been suggested that the 1990s collapse of the Soviet Union and East European socialist systems constituted a fourth wave.

- Layachi, Azzedine (2013) Algeria: The Untenable Exceptionalism in the Spring of Upheavals. In Larémont, Ricardo René (ed.) Revolution, Revolt, and Reform in North Africa. New York: Routledge, pp. 125–147.

- UNDP (2010) ‘The 2010 Human Development Report (The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development)’, Available at: <http://hdr.undp.org/en/humandev/lets-talk-hd/2010-11b/>.

- Extraordinary rendition is defined as “the transfer of an individual, with the involvement of the United States or its agents, to a foreign state in circumstances that make it more likely than not that the individual will be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.” Source: Association of the Bar of the City of New York & Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (2004) ‘Torture by Proxy: International and Domestic Law Applicable to “Extraordinary Rendition”‘, p. 4, Available at: <http://chrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/TortureByProxy.pdf>.

- The Makhzen refers to the informal network of power holders revolving around the monarch. They include royal notables, big businessmen and landowners, tribal leaders, top-ranking security officers and high-level non-elected bureaucrats. The Makhzen makes many important decisions and acts through patronage networks and formal political structures, including political parties, administration and influential power brokers.

- Evans, Martin (2012) ‘Contextualising Contemporary Algeria: June 1965 and October 1988’, Open Democracy, 25 May, Available at: <https://www.opendemocracy.net/martin-evans/contextualising-contemporary-algeria-june-1965-and-october-1988> [Accessed 16 February 2015].

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2009) ‘Algeria: National Reconciliation Fails to Address Needs of IDPs’, Available at: <http://www.internal-displacement.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/algeria/2009/national-reconciliation-fails-to-address-needs-of-idps>[Accessed 16 February 2015].

- Bertelsmann Stiftung (2012) ‘BTI 2012 Algeria Country Report’, p. 23, Available at: <http://www.bti-project.de/fileadmin/Inhalte/reports/2012/pdf/BTI2012Algeria.pdf> [Accessed 18 November 2012].

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (2013) ‘Atlas of Electoral Gender Quotas’, Available at: <http://www.idea.int/publications/atlas-of-electoral-gender-quotas/loader.cfm?csModule=security/getfile&pageID=63855> [Accessed 16 February 2015].

- This coalition collapsed in 2013 and the PJD had to form a new one with pro-monarchy forces in parliament, thereby undermining its ability to have much impact on policy.

- BBC (2011) ‘Islamist PJD Party Wins Morocco Poll’, BBC, 27 November, Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15902703>.

- On the resilience of authoritarianism in MENA, see Bellin, Eva (2004) The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective. Comparative Politics, 36 (2), pp. 139–157.

- See Brumberg, Daniel (2002) The Trap of Liberalized Autocracy. Journal of Democracy, 13 (October), pp. 56–68; Anderson, Lisa (1991) Absolutism and the Resilience of Monarchy in the Middle East. Political Science Quarterly, 106 (Spring), pp. 1–15; Schlumberger, Oliver (ed.) (2007) Debating Arab Authoritarianism. Stanford: Stanford University Press; Lucas, Russell E. (2004) Monarchical Authoritarianism: Survival and Political Liberalization in a Middle Eastern Regime Type. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 36 (February), pp. 103–19; Wegner, Eva (2007) Islamist Inclusion and Regime Persistence: The Moroccan Win-Win Situation. In Schlumberger, Oliver (ed.) op. cit., pp. 75–93; and Albrecht, Holger (2007) Authoritarian Opposition and the Politics of Challenge in Egypt. In Schlumberger, Oliver (ed.) op. cit., pp. 59–74.

- Layachi, Azzedine (2005) Political Liberalization and the Islamists in Algeria. In Bonner, Michael, Reif, Megan and Tessler, Mark (eds) Islam, Democracy and the State in Algeria. New York: Routledge, p. 47.

- Ibid.

- Democracy, the ultimate goal, is understood here as a set of institutions, a process and a corresponding political culture, which allow individuals and groups to have regular input in the policy-making process. It implies the end of authoritarianism, participatory politics, regular elite turnover and accountability, and the transparency of political and economic transactions.